Genius Revisited Revisited

A book study of surveys of the high-IQ elementary school HCES concludes that high IQ is not predictive of accomplishment; I point out that the disappointing results are consistent with the subjects not being geniuses due to regression to the mean (because of extremely early IQ tests) & small sample size.

Genius Revisited documents the longitudinal results of a high-IQ/

gifted-and-talented elementary school, Hunter College Elementary School (HCES); one of the most striking results is the general high education & income levels, but absence of great accomplishment on a national or global scale (eg. a Nobel prize). The authors suggest that this may reflect harmful educational practices at their elementary school or the low predictive value of IQ. I suggest that there is no puzzle to this absence nor anything for HCES to be blamed for, as the absence is fully explainable by their making 2 statistical errors: base-rate neglect, and regression to the mean.

First, their standards fall prey to a base-rate fallacy and even extreme predictive value of IQ would not predict 1 or more Nobel prizes because Nobel prize odds are measured at 1 in millions, and with a small total sample size of a few hundred, it is highly likely that there would simply be no Nobels.

Secondly, and more seriously, the lack of accomplishment is inherent and unavoidable as it is driven by the regression to the mean caused by the relatively low correlation of early childhood with adult IQs—which means their sample is far less elite as adults than they believe. Using early-childhood/

adult IQ correlations, regression to the mean implies that HCES students will fall from a mean of 157 IQ in kindergarten (when selected) to somewhere around 133 as adults (and possibly lower). Further demonstrating the role of regression to the mean, in contrast, HCES’s associated high-IQ/ gifted-and-talented high school, Hunter High, which has access to the adolescents’ more predictive IQ scores, has much higher achievement in proportion to its lesser regression to the mean (despite dilution by Hunter elementary students being grandfathered in). This unavoidable statistical fact undermines the main rationale of HCES: extremely high-IQ adults cannot be accurately selected as kindergartners on the basis of a simple test. This greater-regression problem can be lessened by the use of additional variables in admissions, such as parental IQs or high-quality genetic polygenic scores; unfortunately, these are either politically unacceptable or dependent on future scientific advances. This suggests that such elementary schools may not be a good use of resources and HCES students should not be assigned scarce magnet high school slots.

Hunter Elementary is a small elementary school in New York City enrolling ~50 students each year starting in preschool/

High IQ Background

Parallel to the Hunter Elementary students, but much better known are the Terman study (young, relatively low IQ), Anne Roe’s studies of world-class scientists (generally in their 40s or 50s), and the SMPY and TIP longitudinal studies (almost identical cutoffs but measured in middle school ~12yo using SATs, similar to Hunter High admission); some relevant publications:

Anne Roe’s series of papers & book

TIP: “When Lightning Strikes Twice: Profoundly Gifted, Profoundly Accomplished”, et al 2016

SMPY: due to length (several hundred papers/

books), see my SMPY bibliography 2013, “Investigating America’s elite: Cognitive ability, education, and sex differences”

Research strongly supports the high predictive power of IQ for adult accomplishment. We can also note in general that the NYC magnet high schools like Stuyvesant are justly famous for the accomplishments of alumni, as are the French schools like the Lycée Louis-le-Grand (feeders into the grandes écoles like ENS) or the Russian Kolmogorov school (1993) at Moscow University; and the rate of alumni accomplishment only increases when one considers highly-intellectually-selective institutions of higher education like Caltech or MIT.

I came across Genius Revisited while looking into the question of inferring ethnic composition of the SMPY/

Aside from trying to track down a reference for Murray’s Jewish claim (which turned out to not be mentioned in the book aside from the overall Jewish percentage), while a high school for the gifted makes sense, I had some doubts about whether such an elementary school made sense and was curious how it had turned out.

HCES Results

To summarize the results: contrary to stereotypes that “bookish, nerdy, socially inept, absentminded, emotionally dense, arrogant and unfriendly, and that they are loners”, high IQ children are physically and psychologically healthy, if not healthier; they are often socially capable; adult accomplishment and eminence increase with greater intelligence, with no particular ‘threshold’ visible at places like IQ 130, and even with extremely high ability in all areas, people tend to eventually specialize in their greatest strength which is their comparative advantage; happiness is not particularly greater; male and female differences in achievement exist but are at least partially driven by other sex-linked differences in preferences, particularly choice of field and work-life balance; particular ethnicities are under or overrepresented as one would calculate using the normal distribution from the study-specific cutoffs and ethnic means; and overall educational credentials are much more common in the later groups than the earlier ones.

So what does Genius Revisited report? In general, it is surprisingly light on detailed quantification or analysis. Income and education are reported only cursorily; adult achievements are not gone into any sort of detail or categorization only than vague generalizations about there being lots of doctors, professors, and executives etc. They do not report adult IQs, or attempt any statistical analysis to compare IQs at admittance, graduation, or when contacted as adults, whether some subtests predict adult accomplishment better than others, whether there were differential regressions to the mean or whether there was any regression to the mean observed by graduation2, or comparison of any dropouts/

From this perspective, the book is quite a disappointment, as there are not many high IQ longitudinal datasets around—yet they waste the opportunity. Some further details and more fine-grained categorization of a few of the hundred variables collected are reported in et al 1989 but the treatment is much less than it could have been.

What it does do is attempt as a sort of narrative ethnography by piecing together many quotes from the students about their Hunter Elementary experience and later life. This is interesting to me on a personal level because my parents had considered sending me to the Long Island School for the Gifted but ultimately decided against it; so in a way, reading their memories is a glimpse of a path not taken. The picture that emerges confirms in many respects the portrait of children in Terman/

There is also a short comparison with Hunter Elementary in the 1990s; apparently much the same as in the 1960s, with the main interesting change that Hunter Elementary has added a racial quota for black students, but Subotnik et al claim that the mean IQ scores have not fallen substantially. It would be interesting to know exactly how much it has fallen, how many of the black students have immigrant parents, and how many students are now of East Asian descent.3

Overall, the writing is clear and there is, if anything, insufficient technical jargon. Some dry humor appears in spots (eg. in et al 1989, a wry comment on rent control and the difficulties of longitudinal studies: “the only addresses on file were those of the parents while the child attended the school. Fortunately, given the state of the New York City housing market, checking those addresses against the 198837ya Manhattan phone book proved to be fairly productive”).

Disappointingly Average

Subotnik et al generally seem to hold what has been called the ‘resource’ model of gifted education: high IQ children have much better odds of growing up into the great movers & shakers and thinkers of the world who have disproportionate influence on what happens (definitely); that special measures such as enriched education, schools with peers in intelligence, and accelerated courses will increase the yield of great (maybe); and that the increase justifies the upfront expenses (uncertain).

By success, they have high standards; Gallagher’s foreword speaks for the rest of the book when it says:

The authors were disappointed to discover that although this sample succeeded admirably in traditional terms, with its share of physicians, lawyers, and professors, there were no creative rebels to shake society out of its complacency or revolutionize a field.

Further:

Norbert Wiener, in his book The Autobiography of an Ex-Genius [actually, Ex-Prodigy: My Childhood and Youth & I Am Mathematician], detailed his unhappy family life with a domineering father and enough personal problems to be in and out of mental institutions. Yet, it was this Norbert Wiener who gave the world cybernetics that revolutionized our society. What if he had had a happy family life with a warm and agreeable father? One is left to wonder whether Wiener would have had the drive and motivation to make this unique contribution. The same question can be posed for these Hunter College Elementary School graduates. Are many of them too satisfied, too willing to accept the superior rewards that their ability and opportunity have provided for them? What more could they have accomplished if they had a “psychological worm” eating inside them—whether that worm was low self-concept or a need to prove something to someone or to the world—that would have driven these people to greater efforts. What if their aptitudes had been challenged in a more hard-driving manner, like Wiener’s experience, into the development of a specific talent? This book raises many important, sometimes disturbing issues… The authors raise some disturbing issues regarding the purposes of schools for the gifted. Indeed, just what is the contemporary rationale for funding schools or programs for the highly gifted student? If one is looking to such an institution as a source of leading students towards societal leadership (or, as the authors suggest, “a path to eminence”), then the Hunter College Elementary School of the past failed to realize such an aspiration. Indeed, this goal may well be beyond the reach of any elementary school…the [Hunter College] High School seeks to enhance students’ commitment to intellectual rigor and growth, develop opportunities for specialization, and commitment to caring and compassion. Will such a rationale foster more students down the path towards genius? The research literature and the current study would indicate that such a condition is a necessary but not sufficient condition to move students into making ground-breaking discoveries or toward professional eminence. Does it follow then that such schools should not exist? Or at least, not at public expense? I would vigorously argue against both reactions.

This appraisal of failure has been echoed by people citing Genius Revisited like Malcolm Gladwell.4

This fits with the general description of the Hunter Elementary cohort on pg3–4:

The mean IQ of the Hunter sample was 157, or approximately 3.5 standard deviations above the mean, with a range of 122 to 196 on the L-M form.

…Each class at Hunter College Elementary School from the years 194877ya to 196065ya contained about 50 students, yielding a total possible population of 600 graduates…35% of the total population of 1948–12196065ya HCES students (n = 210) completed and returned study questionnaires

…Religious Affiliation: The Hunter group is approximately 62% Jewish, although they describe themselves as Jews more in terms of ethnic identity than religious practice. The group, as a whole, is not religious.

Educational Attainments: Over 80% of the study participants held at least a Master’s degree. Furthermore, 40% of the women and 68% of the men held either a Ph.D, LL.B., J.D., or M.D. degree.

Occupation and Income: Only 2 of the HCES women identified themselves primarily as homemakers. 53% were professionals, working as a teacher at the college or pre-college level, writer (journalist, author, editor), or psychologist. The same proportion of HCES men were professionals, serving as lawyers, medical doctors, or college teachers. The median income for men in 198837ya was $225,250$75k1988 (range = $1,501,665$500k1988) and for women $120,133$40k1988 (range = $507,563$169k1988). Income levels were statistically-significantly different for men and women, even when matched by profession. For example, the median income for male college teachers or psychologists was $150,166$50k1988 and for females, $90,100$30k1988.

By regular standards, this is a remarkably high degree of accomplishment. Even now, only a small fraction of the population can be said to hold a “Ph.D, LL.B., J.D., or M.D.”, but in the Hunter Elementary cohort, you could hardly throw a rock without hitting a professor (16% of men), who would then be able to turn to the person standing next to them to have their wound treated (18% doctors), and turn to the person on the other side in order to sue you for assault (20% lawyers). For this cohort, the education baseline would be more like <7%, not >80%. et al 1989 breaks it down a little more precisely in Table 2 “Highest Degree Attained”: for men, 4% not available, 20% Bachelors, 43% Masters, 40% Ph.D/

But it doesn’t fit the definition of great accomplishments. They mention no one winning a Nobel, or a Pulitzer, or being globally famous. Thus, in a real sense, Hunter Elementary has failed, and with it (the authors imply), the idea that IQ is the driving force behind greatness; thus, Subotnik et al spend much of the book, and other publications, pondering what is missing. If IQ is merely a necessary factor or threshold, but one that still leaves such a high chance of an ordinary life, what really makes the difference? Is the crucial ingredient a drive for mastery? Did Hunter Elementary accidentally quash students’ ambitions for a lifetime by de-emphasizing competition and grades? Or (as the other half of surveyed students maintained), did it have too much competition and broke the students mentally? Was Hunter Elementary too well-equipped a cocoon, leaving students unprepared for Hunter High and the real world, or not enough? Did the home environment determine this, or the curriculum? Did the broad academic curriculum leave students ‘a mile wide and an inch deep’ and lacking in fundamentals acquired by drilling and repetition?

Sample Size

But should we declare it a failure, considering the parallel lines of evidence from Roe, SMPY, and TIP? The mentioned standard is a high bar indeed. What percentage of the population can be truly said to ‘revolutionize a field’? It’s a lifetime’s work just to truly understand a field and reach the research frontier and make a meaningful contribution, and most of the population generally doesn’t even try but pursue other goals. Out of 600 students, is it reasonable to consider the Hunter Elementary experiment a failure because none has (yet—the Nobel Prize is increasingly delayed by decades)? As Gallagher then points out:

…Yet, there are very few such individuals alive in any particular era. The statistical odds against any one of them having graduated from one elementary school in New York City is great. Whether the “creative rebel” would have survived the selection process at Hunter, or any similar school, is one of those remaining questions that should puzzle and intrigue us.

If we consider the STEM Nobel Prizes, the USA has perhaps 1 per million people. So if even 1 HCES student had won a STEM Nobel out of 210, or 600, that would imply an enormous increase in odds ratio of >1666359ya; or to put it another way, if we genuinely expected 1 or more Nobels from our HCES alumni, then to achieve that >1666359ya increases in odds with only +57 early-childhood IQ points, we’d also have to believe something along the lines of each individual IQ point on average increasing the odds by 29effect sizes, we would still frequently expect to observe a HCES-sized cohort to not win a Nobel (eg. if we had expected 1 Nobel prize per 600, for a probability of 1⁄600 per student, then the probability of seeing 0 Nobels in n = 600 is high: (1 − 1⁄600)600 = 0.367; to drive the non-Nobel probability down to <5%, we would have to expect ≥3 Nobels per 600).

One is reminded of the oft-head criticism of the Terman study for failing to enroll William Shockley & Luis Alvarez, the former of whose known IQ test scores as an 8–9yo fell short by ~11 points of the nominal threshold (or 6 points for special-cases Terman might admit): a sample of hardly 1500 children, whose selection was inevitably imperfect5, particularly when pioneering longitudinal studies, is supposed to contain all the Nobelists from a population at least 100 times the size (the screening population was nominally >168,000 Californian children), or else this debunks IQ somehow. What method of selection could accomplish this feat is never specified, nor do critics concede that it is impressive that IQ tests could come so close to picking out the children in elementary school who had a chance of many decades later becoming Nobelists despite all the limitations the Terman study labored under (like using a verbal-heavy IQ test). From a purely statistical perspective, given what is known about the instability of childhood test scores and regression to the mean and the relatively small Terman sample combined with the extreme rarity of Nobel prizes and randomness, the Terman study would be expected to miss at least one future Nobelist the majority of the time ( et al 2019).

So it’s unclear how much weight we ought to put on the apparent ‘failure’ of the HCES alumni, because even the ludicrously optimistic model is consistent with often seeing ‘failure’.

Alumni

How many people from Hunter Elementary and from Hunter High come anywhere close to being nationally famous?

If we were to double-check in Wikipedia by looking for ‘Notable’ people whose entries link to Hunter Elementary, perhaps because they were students there, we find painter Margaret Lefranc, linguist E. Adelaide Hahn, and minor actor Fred Melamed, and Supreme Court justice Elena Kagan (but while her mother taught at Hunter Elementary, she herself went to Hunter College High School—along with at least 95 other ‘Notable’ people). I later learned that Hamilton star Lin-Manuel Miranda and scientist Adam Cohen also went to Hunter Elementary as well as High.

Triple-checking in Google, this does seem to be a fair accounting—no billionaires or Nobelists suddenly pop out. If we were to judge by Wikipedia entries, it would seem that Hunter Elementary can claim around 5 ‘Notable’ alumni while Hunter High can claim 96. (Checking the 96 WP entries by hand, most omit mention of the elementary school or whether they passed exams to get into Hunter High, but the ones who do always specify exams or a non-Hunter Elementary; only 1 entry, the group entry for the hip-hop band Dujeous, turns out to include a Hunter Elementary member: Loren Hammonds/

This is not because Hunter High is 32× larger than Hunter Elementary: Hunter Elementary currently accepts ~50 students per year while Hunter High currently accepts ~175 + 50 grandfathered in from Hunter Elementary (total ~225), and is only 4.5× bigger—3.5× if we exclude the Hunter Elementary alums (who do not appear in the 95+ listed, apparently). Even more strikingly, while I do not recognize the names of Lefranc, Hahn, Melamed, or Adam Cohen, I do recognize several names on the Hunter High list (Kagan, of course, but also Bruce Schneier, Mark Jason Dominus, some rappers in passing).

This would imply that Hunter High grads are much more likely to achieve WP ‘Notability’ than Hunter Elementary grads: something like 8 times more likely. It is also worth noting that some other selective urban schools pass the ‘Nobel test’: Lowell High School in SF, for example, boasts 3 Nobel laureate alumni (Michelson, Erlanger, & Cornell); Stuyvesant High School claims (Lederberg, Fogel, Hoffmann, & Axel).

Why?

Another way would be to ask what should we expect, from a statistical and psychometric point of view, from Hunter Elementary students, given the procedures and tests used? There are a number of statistical issues which can arise in intelligence research particularly: range restriction such as ceiling/

Weak Childhood IQ Scores: Regression To The Mean

Regression to the mean is pervasive: individual data points which are “unusual” in some way will tend to be associated with more “usual” data points. If you run unusually fast one day, you will probably run slower than that the next day—or the day before; if you weigh unusually little on your bathroom weight scale one morning, and you immediately weigh yourself again, you will probably ‘gain weight’ to a more usual weight; while if a relative is unusually morbidly obese, you are more likely to be overweight, but not as overweight as them. So, unusually successful parents will tend to have more usually (ie. less) successful children; and also unusually successful children will tend to become more usually successful adults. This is true of every trait, whether height or IQ.

Hunter Elementary uses IQ testing of ~5yo children, selecting those >IQ 140 and getting a mean of IQ 157 (3.8 SDs); these children are then kept enrolled in Hunter Elementary and grandfathered into Hunter High as long as their grades stay reasonable, with expulsions and transfers apparently rare (and little mentioned in the book). This is fine as far as the 5yo children go… but what about them as adults?

As is well known, childhood IQs are imperfect predictors of final adult IQs, for neurological, developmental, and genetic reasons; the best possible measurement at 5yo will only correlate with adult IQ at perhaps r = 0.5–0.6. (Reliabilities/

Such a correlation is considerable, and similar to the correlation of years of education & IQ, but it is also far from the r = 1 implicitly assumed by Subotnik et al when they casually talk of their students as adults having IQ 150+ simply because, long ago, as small children, they had nominal test scores that high.

Such a correlation implies that the childhood IQ test scores are being driven by, as much as their ultimate intelligence, factors like precocity, patience for testing and conformity, and simple randomness6; by selecting this early, one is selecting less for extremely intelligent adults than for cognitively fast-developing children, which is not the same thing.

And having been selected for scoring extremely high on a particular test, Hunter Elementary kids must revert to mediocrity (a phenomenon described by Galton well before any IQ test was developed, and which all psychometricians are mindful of, especially in any kind of test-based selection process).

What can we estimate their adult IQs to be? Since the majority of students are Jewish (or these days, split between those of Jewish and East Asian descent) whose mean is usually estimated at something like 110, we could predict that their adult IQs will not average 157, but will average 110 + (157 − 110) × 0.5 = 133. (Note that if we do not grant this assumption, the regression to the mean would be more severe: 100 + (157 − 100) × 0.5 = 128.)

133 IQ is nothing to sneeze at, but it is also only +2.2SDs and closer to 1 in 50 than 1-in-10,000; a Hunter Elementary school grad as an adult could easily not even qualify for Mensa. Or to put it another way, with 260 million people in the USA in 199332ya, there were around 3.6 million people with IQs ≥133, of which the total Hunter Elementary cohort would represent 0.016%. If we consider cohorts of 600 children with adult mean IQs of 133, not many of them will be >157 at all—only 5% or ~32 students (mean(replicate(100000, sum(sort(rnorm(600, mean=133, sd=15))>157))))! The others will have developed into adult IQs below that, possibly much below that. This calculation doesn’t require any knowledge of outcomes and could have been done before Hunter Elementary opened: inherently, due to the limits of IQ tests in screening for extremely gifted adults based on noisy early childhood tests, most ‘positives’ will be false positives. (This is the same as the famous mammography or terrorist screening examples of how an accurate test + low base-rate = surprisingly high false positive rate and low posterior probability.)

Subotnik et al appear entirely ignorant of this, particularly in chapter 9, as they repeatedly state or quote former Hunter students echoing estimates like “160 IQ”, at face-value, and are puzzled at the failure of HCES students to attain the pinnacles of global success and ponder whether HCES damaged them by fostering mediocrity & crushing ambition, which is to reach for explanations for something which requires no explanation. (This is particularly ironic given that they contrast the ‘failure’ of HCES with the success of other institutions, such as the Illinois University High School.)

More Precise Testing: High School Age

What about Hunter High? Hunter High tests 6th graders who enroll as 7th graders; 6th graders tend to be ~11yo, not 4–5yo. One correlation quoted by Eysenck is testing 11yos can have a correlation of ~0.95 with adult scores; so Hunter High grads, assuming they had the same mean (I haven’t seen any means quoted), would expect to revert to mediocrity down to 110 + (157 − 110) × 0.95 = 154 ie almost identical. (With a correlation of 0.9, 152, and so on). So out of 600 Hunter High alums, 252 will remain >157, or ~8× the Hunter Elementary rate.

That is, the overrepresentation of Hunter High graduates among Hunter-related Notable figures is almost identical to their overrepresentation among Hunter-related graduates who maintain their elite IQ status.

None of the materials I have read on Hunter Elementary, aside from one article in New York magazine7 drawing on 2006’s “Gifted Today but Not Tomorrow? Longitudinal changes in ability and achievement during elementary school”, have mentioned the issue that IQ tests in such early childhood are simply not that predictive in finding extreme tails, or even alluded to it as a problem, so I have to wonder if Subotnik et al8 appreciate this point: from basic psychometric principles, we would predict that Hunter Elementary graduates will not be extraordinarily intelligent, will represent only the tiniest fraction of the population of intelligent people, and thus their adult accomplishment will not be out of line with what we observe—solid academic and social achievement. Nor is there any particular reason to attribute their ‘failure’ to the atmosphere or curriculum or methods of Hunter Elementary itself.

Implications for Gifted Education

Given this, we would have to conclude that the idea of a gifted & talented elementary school is difficult to justify on the resource paradigm related to focusing resources on students’ with future adult intelligence >150 as only a small fraction of such students are findable with current IQ testing methods at that age, but that it makes far more sense to screen at a later age like 11yo and concentrate resources at high school or college levels. If we concluded that the gain from better education of those 5% in an elementary school is profitable and so a Hunter-like elementary school is a good idea, we should definitely not automatically enroll all such elementary school students in an even more expensive Hunter-like high school: each such grandfathered student is worth ~1⁄8th an outsider student in terms of potential. It would be much better to not grandfather the elementary school students—they have already been highly advantaged by the enriched education & peers, after all, so why should they be given an additional huge advantage over all the students outside the system who are equally deserving of the chance? The main reason would seem to be some sort of ‘family’ or loyalty sentimental reasoning; if this bias cannot be overcome, the idea of a single vertically integrated feeder system may be actively harmful to gifted education.

Improving HCES?

Matters could be improved, though, with more broad-ranging tests.

For example, genetics: as adult IQ is a highly heritable trait with perhaps up to 80% of variance predictable from all genetic variants and >~50% predictable from all SNPs, with the heritability increasing with age and only ~25% at age 5 (the Wilson effect, 2013), predictions of adult IQ based on 5yo testing could be improved substantially using their parents’ & siblings’ IQs, or by direct genetic prediction; this would help identify the children who are rejected because of developmental quirks but who would eventually live up to their genetic potential.

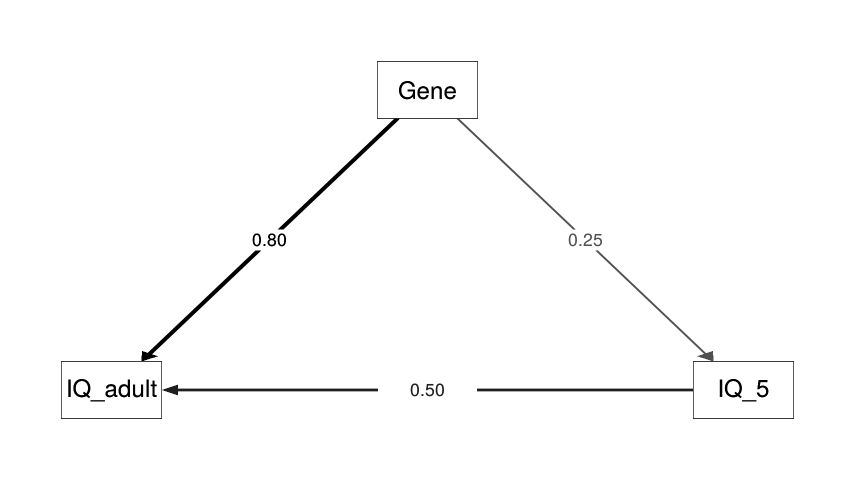

If we consider a path model with genes → IQ (0.50), IQ5yo → IQ (0.50), genes → IQ5yo (0.25):

Path model relating childhood IQ measured at age 5, final adult IQ, and SNP heritability

Then using an ideal SNP genetic score and a 5yo IQ test, one could expect to predict 0.5 + (1 − 0.25) × 0.5 = 0.875 or 87% of variance, giving a prediction/

In that scenario, we could create a Hunter-like Elementary school which is as good at filtering as Hunter High is. While it’s unclear when we will be able to predict 50% of variance in adult IQs based on polygenic scores, in the near future we can hope for polygenic scores on the order of 10%, which would still be helpful: PGS = 0.10; 110 + (157 − 110) × √(PGS + (1 − 0.25) × 0.5) = 142.4. Besides waiting for better polygenic scores, other factors could be included in a predictive model such as parental IQs and income/

Ultimately, it would seem that the most justifiable reason for running Hunter Elementary is the reason that comes across most clearly reading the alumni reminiscences: because they would have been miserable in regular schools. If early-developing children must be subjected to mandatory formal education, then it should at least be with their peers.

See Also

External Links

“Is Gifted Education a Bright Idea? Assessing the Impact of Gifted and Talented Programs on Students”, et al 2014

“The Elite Illusion: Achievement Effects at Boston and New York Exam Schools”, et al 2014

“Effects of elite high schools on university enrolment and field of study choice”, et al 2018

“Achievement gains from attendance at selective high schools”, 2018

Appendix

-

1947, “Psychological Approaches To The Study Of Genius”, Occasional Papers on Eugenics #4. In a similar vein, Anne Roe (pg49, Creativity ed 1970) notes that 5 of her 64 world-class scientists were Jewish.

-

Several passages mention that the students were repeatedly tested throughout their education, so it should’ve been entirely possible to look at IQ scores longitudinally and note how much they declined since admission, although it also seems possible that this decline will be masked by the constant testing leading to test-specific training and loss of validity in measuring g.

-

For comparison, Hunter High has always used only an exam for admission, aside from the grandfathered Elementary students, and a 201015ya NYT article on a small flareup of the controversy prompted by a black-Hispanic student’s speech, says “In 199530ya, the entering 7th-grade class was 12% black and 6% Hispanic, according to state data. This past year, it was 3% black and 1% Hispanic; the balance was 47% Asian and 41% white, with the other 8% of students identifying themselves as multiracial. The public school system as a whole is 70% black and Hispanic.” These order statistics are about as expected given different group means & the selectivity of HCES.

-

“Getting In: The social logic of Ivy League admissions”

But what did Hunter achieve with that best-students model? In the 1980s, a handful of educational researchers surveyed the students who attended the elementary school between 194877ya and 196065ya. [The results were published in 199332ya as Genius Revisited: High IQ Children Grown Up, by Rena Subotnik, Lee Kassan, Ellen Summers, and Alan Wasser.] This was a group with an average I.Q. of 157—three and a half standard deviations above the mean—who had been given what, by any measure, was one of the finest classroom experiences in the world. As graduates, though, they weren’t nearly as distinguished as they were expected to be. “Although most of our study participants are successful and fairly content with their lives and accomplishments”, the authors conclude, “there are no superstars . . . and only one or two familiar names.” The researchers spend a great deal of time trying to figure out why Hunter graduates are so disappointing, and end up sounding very much like Wilbur Bender. Being a smart child isn’t a terribly good predictor of success in later life, they conclude. “Non-intellective” factors—like motivation and social skills—probably matter more. Perhaps, the study suggests, “after noting the sacrifices involved in trying for national or world-class leadership in a field, H.C.E.S. graduates decided that the intelligent thing to do was to choose relatively happy and successful lives.” It is a wonderful thing, of course, for a school to turn out lots of relatively happy and successful graduates. But Harvard didn’t want lots of relatively happy and successful graduates. It wanted superstars, and Bender and his colleagues recognized that if this is your goal a best-students model isn’t enough.

Gladwell omits any discussion of why Caltech or MIT or other highly selective institutions do reliably produce “superstars” by operating on a “best-students model”, and not merely “relatively happy and successful graduates”, if such selection is ineffective.

-

For example, 2019 notes that 2.7% of the Terman sample was enrolled because their tests were scored completely wrong, and their actual IQ scores as children were as low as 106.

-

Longitudinal twin studies show that monozygotic twins become increasingly similar over time, while dizygotic twins do not; the high genetic correlations between ages implies that the early large differences between monozygotic twins reflect random /

non-shared-environment effects, but that their identical genetics gradually regress them towards each other & a common mean. -

Consider, for instance, Hunter College Elementary School, perhaps the most competitive publicly funded school in the city. (This year, there were 36 applicants for each slot.) 4-year-olds won’t even be considered for admission unless their scores begin in the upper range of the 98th percentile of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, which costs $433$2752010 to take. But if they’re accepted and successfully complete third grade (few don’t), they’ll be offered admission to Hunter College High School. And since 200223ya, at least 25% of Hunter’s graduating classes have been admitted to Ivy League schools. (In 200619ya and 200718ya, that number climbed as high as 40%.) Or take, as another example, Trinity School. In 200817ya, 36% of its graduates went to Ivy League schools. More than a third of those classes started there in kindergarten. 30% of Dalton’s graduates went to Ivies between 200520ya and 200916ya, as did 39% of Collegiate’s and 34% of Horace Mann’s. Many of these lucky graduates wouldn’t have been able to go to these Ivy League feeders to begin with, if they hadn’t aced an exam just before kindergarten. And of course these advantages reverberate into the world beyond.

…Those who are bullish on intelligence tests argue they’re “pure” gauges of a child’s mental agility—immune to shifts in circumstance, immutable over the course of a lifetime. Yet everything we know about this subject suggests that there are considerable fluctuations in children’s IQs. In 198936ya, the psychologist Lloyd Humphreys, a pioneer in the field of psychometrics, came out with an analysis based on a longitudinal twin study in Louisville, Kentucky [the “Louisville Twin Project”], whose subjects were regularly IQ-tested between ages 4 and 15. By the end of those 11 years, the average change in their IQs was 10 points. [I am unable to find the original but see reliabilities in 1983 & 1988. –Editor] That’s a spread with important educational consequences. A 4-year-old with an IQ of 85 would likely qualify for remedial education. But that same child would no longer require it if, later on, his IQ shoots up to 95. A 4-year-old with an IQ of 125 would fall below the 130 cutoff for the G&T programs in most cities. Yet if, at some point after that, she scores a 135, it will have been too late. She’ll already have missed the benefit of an enhanced curriculum.

These fluctuations aren’t as odd as they seem. IQ tests are graded on a bell curve, with the average always being 100. (Definitions vary, but essentially, people with IQs of 110 to 120 are considered smart; 120 to 130, very smart; 130 is the favorite cutoff for gifted programs; and 140 starts to earn people the label of genius.) If a child’s IQ goes down, it doesn’t mean he or she has stopped making intellectual progress. It simply means that this child has made slower progress than some of his or her peers; the child’s relative standing has gone down. As one might imagine, kids go through cognitive spurts, just as they go through growth spurts. One of the classic investigations into the stability of childhood IQ, a 197352ya study by the University of Pittsburgh’s Robert McCall and UC-San Diego’s Mark Appelbaum and colleagues ( et al 1973), looked at 80 children who’d taken IQ tests roughly once a year between the ages of 2½ and 18. It showed that children’s intellectual trajectories were marked by slow increases or decreases, with inflection points around the ages of 6, 10, and 14, during which scores more sharply turned up or down. And when were IQs the least stable? Before the age of 6. Yet in New York we track most kids based on test scores they got at 4. (And we may not even be the worst offenders: As Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman note in their new book, NurtureShock, there are cities with preschools that require IQ tests off 2-year-olds.) “How can you lock children into a specialized educational experience at so young an age?” asks McCall. “As soon as you start denying kids early, you penalize them almost progressively. Education and mental achievement builds on itself. It’s cumulative.”

…Most researchers in the field of childhood development agree that the minds of nursery-school children are far too raw to be judged. Sally Shaywitz, author of Overcoming Dyslexia, is in the midst of a decades-long study that examines reading development in children. She says she couldn’t even use the reading data she’d collected from first-graders for some of the longitudinal analyses. “It simply wasn’t stable”, she says. I tell her that most New York City schools don’t share this view. “A young brain is a moving target”, she replies. “It should not be treated as if it were fixed.”

In 200619ya, David Lohman, a psychologist at the University of Iowa, co-authored a paper called “Gifted Today but Not Tomorrow? Longitudinal changes in ability and achievement during elementary school” in the Journal for the Education of the Gifted, demonstrating just how labile “giftedness” is. It notes that only 45% of the kids who scored 130 or above on the Stanford-Binet would do so on another, similar IQ test at the same point in time. Combine this with the instability of 4-year-old IQs, and it becomes pretty clear that judgments about giftedness should be an ongoing affair, rather than a fateful determination made at one arbitrary moment in time. I wrote to Lohman and asked what percentage of 4-year-olds who scored 130 or above would do so again as 17-year-olds. He answered with a careful regression analysis: about 25%…I wrote Lohman back: Was he certain about this? “Yes”, he replied. “Even people who consider themselves well versed in these matters are often surprised to discover how much movement/

noise/ instability there is even when correlations seem high.” He was careful to note, however, that this doesn’t mean IQ tests have no predictive value per se. After all, these tests are better—far better—at predicting which children will have a 130-plus IQ at 17 than any other procedure we’ve devised. To have some mechanism that can find, during childhood, a quarter of the adults who’ll test so well is, if you think about it, impressive. “The problem”, wrote Lohman, “is assigning kids to schools for the gifted on the basis of a test score at age 4 or 5 and assuming that their rank order among age mates will be constant over time.” …In Genius Revisited, Rena Subotnik, director of the American Psychological Association’s Center for Gifted Education Policy, undertook a similar study, with colleagues, looking at Hunter elementary-school alumni all grown up. Their mean [childhood] IQs were 157. “They were lovely people,” she says, “and they were generally happy, productive, and satisfied with their lives. But there really wasn’t any wow factor in terms of stellar achievement.”

…If you’re looking for practical answers though, Plucker, of Indiana, has a modest proposal. He suggests that schools assess children at an age when IQs get more stable. And in fact, that’s just what City and Country, one of Manhattan’s more progressive schools, does. Standardized tests aren’t required of their applicants until they’re 7 or older. “That way, the kids are further along in their schooling”, explains Elise Clark, the school’s admissions director. “They’re used to an academic setting, they can handle a test-taking situation, and overall, we consider the results more reliable.”

-

Subotnik in particular seems to have not expected such regression to the mean ( et al 2011):

In 200322ya, Subotnik commented on the surprise she had felt a decade before at realizing that graduates of an elite program for high-IQ children had not made unique contributions to society beyond what might be expected from their family SES and the high-quality education they received (see Subotnik, Kassan, et al 199332ya), and posed the following question to readers: “Can gifted children grown up claim to be gifted adults without displaying markers of distinction associated with their abilities?” (Subotnik, 200322ya, p. 14).

…However, the disconnect between childhood giftedness and adult eminence (Cross & Coleman, 200520ya; Dai, 201015ya; Davidson, 200916ya; Freeman, 201015ya; Subotnik et al. Hollinger & Fleming, 199233ya; Simonton, 199134ya, 199827ya; Subotnik & Rickoff, 201015ya; VanTassel-Baska, 198936ya), as well as the outcomes of individuals who receive unexpected opportunities (Gladwell, 200817ya; Syed, 201015ya), suggest that there is a much larger base of talent than is currently being tapped.

Cross, T. L., & Coleman, L. J. (200520ya). “School-based conception of giftedness”. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 52–63). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Dai, D. Y. (201015ya). The nature and nurture of giftedness: A new framework for understanding gifted education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Davidson, J. E. (200916ya). “Contemporary models of giftedness”. In L. V. Shavinina (Ed.) International handbook on giftedness (pp. 81–97). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Freeman, J. (201015ya). Gifted lives: What happens when gifted children grow up. New York, NY: Routledge.

1992, “A longitudinal examination of life choices of gifted and talented young women”

1991, “Emergence and realization of genius: The lives and works of 120 classical composers”

VanTassel-Baska, J. L. (198936ya). “Characteristics of the developmental path of eminent and gifted adults”. In J. L. VanTassel-Baska & P. Olszewski-Kubilius (Eds.), Patterns of influence on gifted learners: The home, the self, and the school (pp. 146–162). New York, NY: Teachers College Press

-

While the 2018 state-of-the-art brain imaging predictions of IQ are still far below the current SAT/

IQ correlation, perhaps r = 0.4 versus r > 0.8, variance components estimates ( et al 2016) indicate that the ceiling is extremely high, r < 0.97, and it is possible in theory. -

Although since Murray’s proposal depends on not reporting to people the weighted index of GPA+SAT-IIs (which is equivalent to the SAT-I) so they don’t get a single memorable number to pride themselves on, a genetic predictor could be split up likewise.

-

This is corrected for range restriction, as is necessary since we are interested in selection (predicting among students before college admission) rather than post-selection. It would be a mistake to, say, correlate GRE with graduate school grades and conclude that the GRE is not predictive, since the GRE was used to select the students in the first place—its predictions have already been ‘used up’.

-

Not to be confused with SNP heritabilities, which upper bound PGSes computed with only a small subset of genetic variants. SNP heritabilities are typically around a third of full heritability, but the use of SNP-only genetic sequencing & GWASes is an economy, and one I expect will gradually fade away: consumer WGS is already as low as $636$5002019 in 2019, and research like et al 2019 demonstrates why WGS will be more useful.