Creatine Cognition Meta-analysis

Does creatine increase cognitive performance? Maybe for vegetarians but probably not.

I attempt to meta-analyze conflicting studies about the cognitive benefits of creatine supplementation. The wide variety of psychological measures by uniformly small studies hampers any aggregation.

3 studies measured IQ and turn in a positive result, but suggestive of vegetarianism causing half the benefit. Discussions indicate that publication bias is at work.

Given the variety of measures, small sample sizes, publication bias, possible moderators, and small-study biases, any future creatine studies should use the most standard measures of cognitive function like RAPM in a well-powered pre-registered experiment.

Creatine is a chemical found throughout the body in a number of roles; it is most famous for its presence in muscles and enabling greater exertion, but it also plays a role in the nervous system. Some small psychology experiments in healthy adults have found cognitive benefits to supplementation but others disagree (Wikipedia, Examine.com), and these differences may be due to covariates like being vegetarian & hence creatine-deficient.

When small studies conflict, one way to get answers is to try to meta-analyze them into a single more robust summary. In particular, I am interested in whether creatine supplementation increases IQ. One problem here is that the studies may not use enough of the same measures to include in the same meta-analysis; besides that, the studies are likely severely underpowered to detect plausible effects: IQ increases have been often claimed, but have rarely panned out (see, for example, dual n-back) and “extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof”.

Background

While creatine is famous for its athletic uses1, there is also biological evidence suggesting creatine is involved in mental performance, serving as a fast source of energy, creatine-related retardation & disability, correlates between meat-eating and performance etc. For one survey, and a more detailed discussion of the rationale for expecting creatine to help, see 2013; for discussion of the neuroprotective effects, see 2017. An interesting longitudinal correlation between creatine levels and later increased salary is found in et al 2014. And et al 2014 reviews some animal experiments suggesting potential benefits in neurodegenerative diseases like aging.

Experimentally, creatine turns out to boost mental performance in some circumstances (eg. et al 2009 saw the creatine group post-score 4 points higher than controls, or 2002’s less oxygen use during mental arithmetic; Jonathan Toomim recommends it highly, claiming that “I’m more confident that I’ve noticed effects [on mental performance] of creatine than of DnB.”)

These results are a little mixed. There are studies showing benefits in:

Vegetarians (2003)

the elderly ( et al 2007)

However, et al 2008 is a broad null result for healthy omnivores, who are probably most of the readers of this FAQ. (Jonathan Toomim has criticized et al 2008 as statistically weak and using a possibly not sensitive test of mental performance; others have pointed out administered a total (73.8 × 0.03) × (6 × 7) ≈ 93g of creatine, which is less than half that of 2003 and 16% less than et al 2009.)

A 2018 meta-analysis/systematic review, et al 2018, “Effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function of healthy individuals: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials”, reached similar conclusions as I did in 201313ya: some evidence of heterogeneous benefits in a literature which uses too many different measures.

Search

Besides the studies I already knew about through discussion, my own research, Wikipedia, or Examine, I also did several searches for additional studies modeled on the search query creatine AND (IQ OR intelligence OR "Raven's") -mutagen (‘IQ’ turns out to be the name of a mutagen which appears in many contexts with creatine kinase):

Google: up to pg10 of results

Google Scholar: up to pg41

Pubmed: 129 results, reviewed all

APA PsycNET: for just

creatine(more complex queries are apparently not supported), 4 hits (none relevant)ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Full Text and ERIC

all(creatine) AND (all(intelligence) OR all(IQ)): 2 hits

I then set up a Google Alert, a Google Scholar alert, and a Pubmed alert for those searches in case any new studies come out.

Overview

The searches & alerts yielded the following potentially useful studies:

et al 2015 (supplement; while creatine was apparently beneficial, not useful because only pre-supplementation baseline cognitive performance and hypoxia+supplementation cognitive performance was collected, according to the flowchart and supplement, with no supplementation+normal-breathing condition)

We are looking for studies of the effects of creatine on cognitive performance in normal healthy populations under normal conditions (ie. no diseases, no genetic disorders, no exotic conditions like hypoxia).

Usable studies turn out to employ a wide variety of psychological measures:

Study |

Test |

|---|---|

2002 |

Uchida-Kraepelin serial calculation test |

2003 |

Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices; Backward Digit Span |

2006 |

Random movement generation test; forward verbal recall; backwards verbal recall; 4-choice visual reaction time test; Hemmings mood state inventory |

2007 |

Random number generation task; number recall test; four-choice visual reaction time test; Hemmings mood state inventory; NASA-TLX effort sub-scale |

et al 2007 |

Random number generation task; forward verbal recall; backwards verbal recall; forward Corsi Block Tapping test; backward Corsi Block Tapping test; long-term memory test |

et al 2007 |

Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices; Uchida-Kraepelin serial calculation test; Backward Digit Span |

et al 2008 |

Simple reaction time; code substitution; code substitution delayed; logical reasoning symbolic; mathematical processing; running memory; Sternberg memory recall |

et al 2009 |

Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices; Memory Scanning task; Number-Pair Matching task; Sustained Attention task; Arrow Flanker task |

et al 2010 |

Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices; Backward Digit Span |

2011 |

Word recall; reaction-time; vigilance rapid information processing task; Controlled Oral Word Association Test |

et al 2013a |

Forward Digit Span; Backward Digit Span; Mini-Mental State Examination; Stroop Test; Trail Making Test; Delay Recall Test |

Merege- et al 2016 |

Stroop Test; Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; Raven Progressive Matrices; Trail Making Test |

et al 2011 |

Rugby ball passing |

et al 2021 |

Flanker Inhibitory Control and Attention Test; Pattern Comparison Processing Speed Test; Dimensional Change Card Sort Test |

In total, these studies use ~33 distinct measures of cognitive functioning; this heterogeneity renders any summary difficult as most measures were used in only one experiment, and encourages selective reporting. The Hemmings mood state inventory, random number generation task, forward verbal recall, & Uchida-Kraepelin serial calculation test are used in 2 experiments each, but the backward digit span is used in 4 experiments, and the RAPM is used in 4 experiments - so it would be best to analyze those two.

RAPM

Data

I decided to code multiple relevant variables:

diet: if no diet was specified, assume omnivorousness since as little as 5% of Western population are vegetarians

0: omnivore

1: vegan or vegetarian

sleep:

0: no mention is made of sleep deprivation

1: if sleep deprivation in the experimental as opposed to control group

IQ:

0: RAPM

dose: total amount of creatine administered, in grams; average is total amount of creatine divided by number of days on which creatine is taken by a subject

age: average mean of all subjects’ age; medians were treated as means if that was provided instead, and means given of range endpoints if only that was provided

type: creatine can be consumed in multiple forms.

Creatine monohydrate (CM) is the most common, but also used in a study is creatine ethyl ester (CEE). While CEE was developed to allow smaller doses than CM, et al 2009 suggests it breaks down far too fast to be effective and so CEE doses may not be 1:1 equivalent with CM.

year |

study |

n.e |

mean.e |

sd.e |

n.c |

mean.c |

sd.c |

type |

dose total |

dose average |

age |

diet |

sleep |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2003 |

Rae |

25 |

13.7 |

4.1 |

25 |

9.7 |

3.8 |

monohydrate |

210 |

5 |

25.59 |

1 |

0 |

2009 |

Ling |

17 |

120.3 |

5.945 |

17 |

116.1 |

9.086 |

ethyl ester |

75 |

5 |

21 |

0 |

0 |

2010 |

Hammett |

11 |

13.45 |

2.25 |

11 |

11.45 |

3.8 |

monohydrate |

110 |

15.7 |

27.59 |

0 |

0 |

2016 |

Merege-Filho |

35 |

30.4 |

4.6 |

32 |

31.8 |

3.8 |

monohydrate |

13.74 |

1.96 |

11.5 |

0 |

0 |

Results

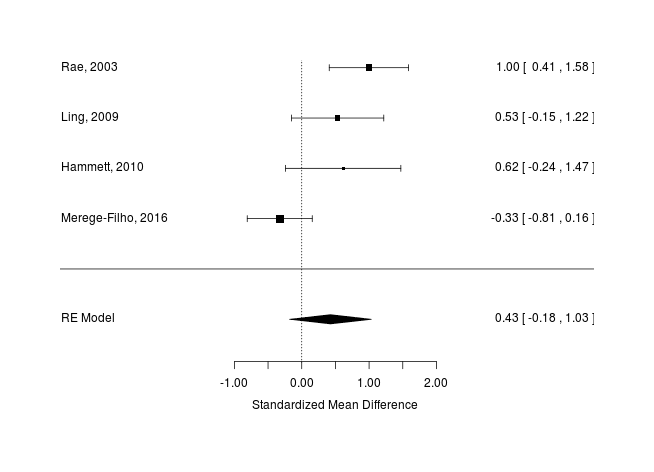

The 4 studies do not turn in a statistically-significant positive result in the random-effects meta-analysis:

Random-Effects Model (k = 4; tau^2 estimator: REML)

tau^2 (estimated amount of total heterogeneity): 0.2731 (SE = 0.3128)

tau (square root of estimated tau^2 value): 0.5226

I^2 (total heterogeneity / total variability): 72.62%

H^2 (total variability / sampling variability): 3.65

Test for Heterogeneity:

Q(df = 3) = 12.8147, p-val = 0.0051

Model Results:

estimate se zval pval ci.lb ci.ub

0.4259 0.3095 1.3761 0.1688 -0.1807 1.0325

A forest plot of the 4 studies

When vegetarianism is used as a covariate (this applies only to 2003), it is not statistically-significant either but does lower the estimate further (given that was also the largest effect):

Mixed-Effects Model (k = 4; tau^2 estimator: REML)

tau^2 (estimated amount of residual heterogeneity): 0.2034 (SE = 0.3213)

tau (square root of estimated tau^2 value): 0.4510

I^2 (residual heterogeneity / unaccounted variability): 64.29%

H^2 (unaccounted variability / sampling variability): 2.80

R^2 (amount of heterogeneity accounted for): 25.52%

Test for Residual Heterogeneity:

QE(df = 2) = 5.9274, p-val = 0.0516

Test of Moderators (coefficient(s) 2):

QM(df = 1) = 1.5477, p-val = 0.2135

Model Results:

estimate se zval pval ci.lb ci.ub

intrcpt 0.2095 0.3261 0.6423 0.5207 -0.4297 0.8487

diet 0.7865 0.6322 1.2441 0.2135 -0.4526 2.0257Unfortunately, with so few studies I can’t investigate dose meaningfully

Publication Bias

The common publication bias checks like the funnel plot are useless with 3 studies. As it happens, there is no need to do any hypothesis-testing here: Ling (personal communication 201313ya) mentions that 2 student theses were done involving creatine supplementation & cognition with apparently uninteresting results, but did not have any copies and the university library had not retained any; this is prima facie publication bias. Hence, we know that the meta-analytic results are biased upwards by publication bias.

Backward Digit Span

Data

year |

study |

n.e |

mean.e |

sd.e |

n.c |

mean.c |

sd.c |

type |

dose total |

dose average |

age |

diet |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2010 |

Hammett |

11 |

11 |

Monohydrate |

110 |

15.7 |

27.59 |

0 |

||||

2003 |

Rae |

25 |

8.5 |

1.76 |

25 |

7.05 |

1.19 |

Monohydrate |

210 |

5 |

25.59 |

1 |

2013 |

Alves |

25 |

3.75 |

1.0 |

22 |

3.25 |

0.76 |

Monohydrate |

25 |

4.17 |

66.8 |

0 |

Results

Source

set.seed(7777) # for reproducible numbers

# TODO: factor out common parts of `png` (& make less square), and `rma` calls

library(XML)

creatine <- readHTMLTable(colClasses = c("integer", "factor", rep("numeric", 6), "factor", rep("numeric", 5)),

"https://gwern.net/creatine")[[2]]

# install.packages("metafor") # if not installed

library(metafor)

cat("Basic random-effects meta-analysis of all studies:\n")

res1 <- rma(measure="SMD", m1i = mean.e, m2i = mean.c, sd1i = sd.e, sd2i = sd.c, n1i = n.e, n2i = n.c,

data = creatine); res1

png(file="~/wiki/doc/creatine/gwern-creatine-forest.png", width = 580, height = 580)

forest(res1, slab = paste(creatine$study, creatine$year, sep = ", "))

invisible(dev.off())

cat("Random-effects with vegetarian covariate:\n")

rma(measure="SMD", m1i = mean.e, m2i = mean.c, sd1i = sd.e, sd2i = sd.c, n1i = n.e, n2i = n.c,

data=creatine, mods = ~ diet)

system(paste('cd ~/wiki/image/creatine/ &&',

'for f in *.png; do convert "$f" -crop',

'`nice convert "$f" -virtual-pixel edge -blur 0x5 -fuzz 10% -trim -format',

'\'%wx%h%O\' info:` +repage "$f"; done'))

system("optipng -o9 -fix ~/wiki/image/creatine/*.png", ignore.stdout = TRUE)Study Details

2002, 2006, et al 2007, 2007, et al 2008, 2011: excluded for not using a measure of intelligence.

et al 2007: excluded for lack of necessary details.

2003

In this work, we tested the hypothesis that oral creatine supplementation (5g daily for six weeks) would enhance intelligence test scores and working memory performance in 45 young adult, vegetarian subjects in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over design. Creatine supplementation had a significant positive effect (p = 0.0001) on both working memory (backward digit span) and intelligence (Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices), both tasks that require speed of processing.

Forty-five vegan or vegetarian subjects (12 males (median age of 27.5, range of 19-37 years), 33 females (median age of 24.9, range of 18-40 years); 18 vegan (median duration of 4.6 years, range of 0.7-17 years) and 27 vegetarian (median duration of 14.3, range of 1-23 years)) were recruited with informed consent from among the student population of The University of Sydney

The study followed a double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over design. Subjects were seen on four separate occasions, at six-week intervals, following an overnight fast to minimize any fluctuations in blood glucose.

A cognitive test battery was also administered. At the end of the first and third test sessions, subjects were given an envelope marked with their study number and containing 5 g doses of supplement (creatine monohydrate ((2-methylguanido)acetic acid); Pan Pharmaceuticals, Australia) or placebo (maltodextrin; Manildra Starches, Australia) in plastic vials. Subjects were asked to consume this supplement at the same time each day for the next six weeks and received advice on how best to take this supplement to ensure maximum solubility and absorption. Subjects returned the envelope with unused vials at the end of each six-week period and the number of vials remaining was used to assess compliance, validated against increases in red cell (tissue) creatine. Between visits 2 and 3, the subjects consumed no supplement. Note: six weeks has been shown to be an adequate ‘wash-out’ period ( et al 1992).

Subjects completed timed (10 min) parallel versions of Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPMs) constructed to have equal levels of difficulty based on the published normative performance data and verified by us on an independent sample of 20 subjects.

Supplementation with oral creatine monohydrate significantly increased intelligence (as measured by RAPMs done under time pressure, figure 1a) compared with placebo (F3 ,33 = 32.3, p , 0.0001; repeated-measures ANOVA). There was no significant effect of treatment order (F1 ,33 = 1.62, p = 0.21), although there was a significant interaction with treatment order (F3 ,99 = 6.7, p = 0.0004). The mean RAPMs raw score under placebo was 9.7 (s.d. = 3.8) items correct in 10 min versus 13.7 (s.d. = 4.1) items correct under the experimental treatment. Supplementation with oral creatine monohydrate (figure 1b) significantly affected performance on BDS (F3 ,34 = 29.0, p , 0.0001), with no effect of order (F3 ,10 2 = 0.98, p = 0.40). Mean BDS under the placebo was 7.05 items (s.d. = 1.19), compared with a mean of 8.5 items under creatine treatment (s.d. = 1.76).

Et Al 2007

“Use of creatine containing preparation eg. for improving memory, retentivity, long-term memory and for preventing mental fatigue condition, comprising eg. Ginkgo biloba, ginseng and niacin” (English translation, original): German patent filed in June 200719ya by Dr. Thomas Gastner, Frauke Selzer, Dr. Hans-Peter, Dr. Bendikt Hammer, for Alzchem Trostberg Gmbh:

Use of a creatine containing preparation for improving memory, retentivity, long-term memory and for preventing mental fatigue conditions, comprising eg. at least a further physiologically effective component of the series Ginkgo biloba, ginseng, taiga root, yam root, lecithin, choline, phosphatidylserine, dimethylamino ethanol, acetyl choline, acetyl-L-carnitine, glutathione, glutamine, cysteine, vitamin A, E, B1, B2, B6, B12, folic acid, pantothenic acid and/or zinc, is claimed. Use of a creatine-component containing preparation for improving memory, retentivity, long-term memory and for preventing mental fatigue conditions, comprising at least a further physiologically effective component of the series Ginkgo biloba, ginseng, taiga root, yam root, lecithin, choline, phosphatidylserine, dimethylamino ethanol, acetyl choline, acetyl-L-carnitine, glutathione, glutamine, cysteine, vitamin A, E, B1, B2, B6, B12, E, niacin, biotin, folic acid, pantothenic acid, zinc, manganese, selenium, magnesium, coenzyme Q10, glucose, colostrum, synephrine, octopamine, caffeine, theophylline, alpha -linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, omega-3-fatty acid, piracetam, aniracetam, memantine, pyritinol, galantamine, vinpocetin, pangamic acid and/or optionally organic or inorganic salts and/or optionally esters, is claimed.

§2, “Effectiveness”:

Subjects were divided randomly into four groups of 25 people each. The age of the subjects varied between 18 and 64 years. The four groups (a-d) were given twice per day for six weeks following each test substances in softgel capsules:

placebo (1500 mg maltodextrin)

creatine monohydrate (1500 mg)

Ginkgo biloba leaves dry extract (120 mg)

creatine monohydrate (1500 mg) and Ginkgo biloba leaves dry extract (120 mg)

It measured:

Backward Digit Span

The number of correctly repeated numbers before supplementation and the number of correctly repeated numbers after six weeks of supplementation are shown in the table. To better compare the results, the difference between the numerical values is further illustrated.

0 weeks

6 weeks

Difference

Placebo (maltodextrin)

6.4

6.8

0.4

Creatine monohydrate

6.2

7.9

1.7

Ginkgo biloba

6.7

7.5

0.8

Creatine monohydrate + Ginkgo biloba

6.5

9.2

2.7

Test Method: Wechsler, D .: Adult Intelligence Scale manual. (195571ya) New York: Psychological Corporation.

Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices

0 weeks

6 weeks

Difference

Placebo (maltodextrin)

8.7

10.2

1.5

Creatine monohydrate

8.1

12.7

4.6

Ginkgo biloba

9.8

12.9

3.1

Creatine monohydrate + Ginkgo biloba

9.3

17.2

7.9

Test Method: Rauen, JC et al .: Manual for Raven’s progressive matrices and vocabulary scales. (198838ya) London: HK Lewis.

Uchida-Kraepelin test

The test subjects a computational test was performed, which measures the mental fatigue. They were given simple computing tasks with an interval of 5 minutes twice 15 minutes. In the second 15 minutes, the number of solved problems per minute were determined. The test was performed before taking supplementation and after 6 weeks. By linear regression analysis can be inferred from the measured data on mental fatigue. In Table 3, the regression coefficient a is given (y = ax + b). An enlargement of the regression coefficient is a direct measure of a reduced mental fatigue.

0 weeks

6 weeks

Difference

Placebo (maltodextrin)

-0.0076

-0.0089

-0.0013

Creatine monohydrate

-0.0088

-0.0046

0.0042

Ginkgo biloba

-0.0105

-0.0081

0.0024

Creatine monohydrate + Ginkgo biloba

-0.0097

-0.0021

0.0075

Test Method: Watanabe, A. et al .: Neuroscience Research (Oxford, United Kingdom) (200224ya), 42 (4), 279-285

But Gastner et al reported only pre and post-test scores, and not standard deviations; nor was any kind of statistical test reported, making it difficult to infer anything about the results.

It is unclear where this experiment was done, by whom, or whether it was ever published. (The “in press” citation to et al 2007 turns out to refer to et al 2007.) Nothing in the English translation indicates that it was published anywhere else; searches failed to find anything related to this but the patent itself; the Uchida-Kraepelin test is unusual and I tried searching for anything relating to it and creatine in Google/Google-Scholar in English & German but turned up nothing besides discussions of 2002.

On 2013-09-23, I attempted to reach Gastner via the Alzchem contact form. (Gastner knows English, as demonstrated by co-authoring “Creatine - its chemical synthesis, chemistry, and legal status” in Creatine and Creatine Kinase in Health and Disease.) 3 months later on 2013-12-14, I mailed a physical letter to the Trostberg, Germany address listed in Creatine and Creatine Kinase (“Degussa AG, Dr. Albert-Frank-Straße 32, D-83308 Trostberg, Germany”). As of 2015-01-08, I have received no responses to any of my attempts.

2009

et al 2009 saw the creatine group post-score 4 points higher than controls

There were 34 participants (including 12 females) who completed the study, with a mean age of 21 years (SD: 1.38; range: 18-24). Participants were excluded, if they presented with a medical history of drug and/or alcohol abuse, diagnosed psychiatric disorders, diabetes, renal insufficiency (kidney dysfunction) or had recently or were currently supplementing with a creatine-based substance. None of the participants was vegetarian.

The final task participants undertook was a modified version of Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (eg. et al 1998) presented on a PC using Macromedia Flash Player [

https://iqtest.dk/main.swf]. The difficulty of the 39 questions gradually increased and was constrained by a 40-min time limit.

The cited iqtest.dk online IQ test contains only one set of questions and does not randomize or vary the selection, implying that subjects answered the same questions twice, which is not good (usually IQ tests will come split in equivalent halves, so one can do pre-tests with the A questions and post-tests with new B questions). This may invalidate the apparent improvement.

At the end of the first testing phase, participants were given a large envelope that contained 15 plastic vials of either 5 g doses of CEE (obtained through the online store Discount Supplements) or a placebo, maltodextrin (obtained from the manufacturer Chemical Nutrition; http://www.cnpprofessional.co.uk).

There was a significant effect of test phase on performance in the IQ test [F(1,32) = 88.98, P < 0.01] with participants scoring a mean of 112 (SD: 9.44) at baseline, and 118 (7.89) at the end of the study. There was no significant main effect of supplement condition [F(1,32) = 0.56, NS]. However, the interaction was significant [F(1,32) = 81.18, P < 0.01]. Pairwise comparisons indicated that participants in the creatine condition performed worse than the placebo group in the first phase of testing, with baseline means for creatine group of 108 (SD: 7.42) and for placebo, 116 (SD: 9.60) (Tukey HSD, P < 0.01). Performance of the creatine group also improved significantly over the supplementation period, with the mean of 108 at baseline increasing to 120 (SD: 5.95) at the end of study (Tukey HSD, P < 0.01). Further pairwise comparisons indicated that there was no significant improvement in the performance of the placebo group over the supplementation period (P > 0.05).

Performance of the creatine group also improved significantly over the supplementation period, with the mean of 108 at baseline increasing to 120 (SD: 5.95) at the end of study

Using the spreadsheet of data Ling provided me:

# ling <- read.csv(stdin(),header=TRUE)

Creatine,IQ

1,120

1,118

1,126

1,121

1,119

1,118

1,125

1,117

1,133

1,116

1,124

1,114

1,110

1,130

1,123

1,116

1,115

2,110

2,112

2,105

2,106

2,115

2,105

2,112

2,124

2,119

2,133

2,116

2,123

2,122

2,110

2,125

2,105

2,131

summary(ling)

# Creatine IQ

# Min. :1.0 Min. :105

# 1st Qu.:1.0 1st Qu.:112

# Median :1.5 Median :118

# Mean :1.5 Mean :118

# 3rd Qu.:2.0 3rd Qu.:124

# Max. :2.0 Max. :133

i <- ling[ling$Creatine==1,]$IQ; mean(i); sd(i)

# [1] 120.3

# [1] 5.945

i <- ling[ling$Creatine==2,]$IQ; mean(i); sd(i)

# [1] 116.1

# [1] 9.086

# we use a _t_-test rather than a Wilcoxon to replicate Ling's probable analysis

t.test(IQ ~ Creatine, data=ling)

# Welch Two Sample t-test

#

# data: IQ by Creatine

# t = 1.608, df = 27.58, p-value = 0.1192

# alternative hypothesis: true difference in means is not equal to 0

# 95% confidence interval:

# -1.163 9.634

# sample estimates:

# mean in group 1 mean in group 2

# 120.3 116.12010

“Dietary supplementation of creatine monohydrate reduces the human fMRI BOLD signal”, et al 2010; quotes relevant for calculating the variables:

To establish whether the magnitude of the BOLD response is influenced by Cr levels, we have measured responses to visual stimuli in the primary visual cortex (V1) of 22 healthy human volunteers using fMRI, before and after oral administration of Cr or a placebo (11 in the Cr group and 11 in the placebo group).

The mean and median age of the Cr group was 30.18 and 27 years (SD = 8.37) respectively and the mean and median age of the placebo group was 25 years (SD = 4.82).

Creatine supplementation (Sci-Mx: Gloucestershire, UK) was provided at a dose of 20 g⧸day for five days, followed by two additional days at a dose of 5 g⧸day.

In order to verify previous reports of cognitive enhancement following Cr supplementation we also measured performance on the Backwards Digit Span (BDS) [28] and Raven’s Advanced Progressive Matrices (RAPM) [24] prior to each scan. The BDS comprises a set of number sequences of increasing length with two different sequences of each length. Subjects were required to repeat each sequence backwards. The test was terminated when the subject failed to repeat two sequences of the same length. Different number sequences were used for the two testing sessions. Subjects were required to complete as many items of the RAPM as possible in 5 min. Since the RAPM tests are ordered in terms of difficulty, odd-numbered and even-numbered tests were administered on weeks 1 and 2 respectively.

Performance on the RAPM increased non-statistically-significantly by 9.6% following Cr (t = 1.882, df = 10, p = 0.0745) and reduced non-statistically-significantly by 4.5% (t = 0.7733, df = 10, p = 0.4572) following placebo. A Group × Week ANOVA revealed a main effect of week (F(1, 20) = 5.75, p = 0.026, two-tailed) and a significant interaction between week and compound (F(1, 20) = 8.58, p = 0.008, two-tailed) for BDS performance. No significant effects were found for RAPM performance.

What’s the standard deviation which produces a p-value of 0.0745 on an increase of 9.6% & a sample size of 11 in each group? Hard to tell, but Hammett provided me the pre/post scores:

pre |

post |

||

|---|---|---|---|

creatine |

mean |

12.27 |

13.45 |

SD |

3.31 |

2.25 |

|

placebo |

mean |

12 |

11.45 |

SD |

3.52 |

3.8 |

Et Al 2013a

The CR and CR+ST groups received 20 g of creatine monohydrate (4 × 5 g⧸d) for five days followed by 5 g⧸d as a single dose throughout the trial.

et al 2013a: combined the placebo & placebo+strength-training groups, and the creatine & creatine+strength-training groups