Review Of Crumb

Autobiographical documentary about ‘underground artist’ Robert Crumb on his 1991 farewell tour, discussing his personality, family, mental health, and source of his graphomanic art.

Review of the 199432ya documentary Crumb about the underground comic artist Robert Crumb & his dysfunctional family on a farewell tour, often meeting each other for the last time.

I conclude that while Crumb is technically skilled & prolific, his work lacks depth and meaning, because they are literally thoughtless: the outpourings of his unconscious after a LSD-triggered psychotic break of a fragile mind, combined with his obsessive cartoon drawing from a young age, enabled an unusual level of “automatic” drawings.

But they are analogous to AI art, and so deeply unsatisfying to anyone to has spent much time with AI art; Crumb’s success was a product of the unique cultural context of the 1960s, particularly psychedelic art, with its low standards for meaning. Despite his attempts to pass on his skills to his children, Crumb’s brand of art is no longer relevant or shocking in today’s world.

1994 documentary about American underground comic artist Robert Crumb; it follows the 48yo Crumb on the occasion of a ‘farewell tour’ in 199135ya as he, his wife Aline Kominsky-Crumb (d. 2022), & young daughter Sophie Crumb prepare to relocate permanently to the French countryside1 (with brief appearances by his first wife’s son, Jesse Crumb). Documentary crew in tow for (mostly) silent filming, he gives some lectures, attends an art show of his work, and revisits most of his surviving relatives—in particular, his older brother Charles Crumb, his younger brother Maxon Crumb, his mother, and an ex-wife in San Francisco. (His father is dead, and his two sisters Carol & Sandra both refused to participate.) They reminiscence about their past.

Inevitably, one watches any documentary or film about a real artist wondering, “how did they do it and how could I have done it too?”

Crumb is the only one which answers that question. (There is, of course, a catch.)

Background

So who is Robert Crumb, anyway? I’ve heard the name often enough, but I don’t know what he’s done. He has no Cerebus or Maus or Watchmen, no Mickey Mouse or Dilbert; he has worked on few or no major comic series, whether Marvel or DC. He has, oddly enough, adapted the Book of Genesis as a comic, but apparently faithfully2, so there’s not much to say about that. I read through his Wikipedia entry and strain to recognize any names—“Fritz the Cat”? Er, maybe, although I suspect I am thinking of some other character from the rubber hose animation era. “Mr. Natural”? Absolutely not.

So if Crumb has no story, no character, no fictional universe, what is he known for? How can he be a world-famous cartoonist? Why do celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio buy his notebooks for millions of dollars?3

The answer seems to be: sheer, exhausting, unmitigated prolificness of drawn comics with unusually good draftsmanship. Just decades upon decades of drawings tumbling out of his pen without end. This is somewhat difficult to film, so the documentary doesn’t focus on that so much as it focuses on Robert Crumb while drawing, as he appears to do little else (and makes this point by repetition).

Crumb the Man

I had read a 2022 NYT profile of Crumb (surprisingly, he is still alive at age 80), and the impression one gets of Crumb is of, well…

A horrible crummy little rat—a vile, cringing man filled with paranoia and resentment towards everything in the world, who the better he is treated by that world (which adulates him and showers him with fame & fortune), merely despises it the more4[^resentment] while sadistically exploiting what tiny crumbs of power he has in petty self-destructive vendettas; a man who will viciously mock and criticize everyone else to your face, leaving you with the certainty that he will start doing so to you too as soon as you leave the room; a small cowardly man whose constant rape fantasies while hiding behind his sketchpad have not resulted in any actual misconduct (as far as we know), mostly because women could punch him in the nose & make him cry5; a man who, despite living in France for 33 years now (approaching half his life), apparently refuses to learn any French; a man who spews not just lazy racist stereotypes & the dumbest sort of liberal shtick you usually would have to seek out in the comments section of Daily Kos, but every other sort of X-ism at some point (untroubled by any kind of consistency); in short, a man who claims to hold up a mirror to a sick society, but holds it the wrong way.

Now, Crumb could not possibly be as bad as all that! Come off it—the profile is not a friendly one, and anyone can be made to look bad by selective quotation and cherrypicking the bad stuff from a career, we all know that, and anyway, he’s such a successful artist. There has to be more to it: “one story is good until another is told”.

So, I looked forward to the documentary to provide greater context and humanize the “Robert Crumb” persona he plays in the media. What is the real Robert Crumb really like…?

Turns out he’s a horrible crummy little rat.

This makes it rather difficult to watch Crumb as there’s little which is not watching Crumb be horrible. Throughout, he cannot stop himself (despite the filming) from criticizing & nasally mocking where not cringing away from the camera; even when invited to give a valedictory lecture to eager students, he simply uses it to rant and complain about injustices from half a century before, like the time that a company paid him merely $10,000 for a single drawing (notably failing to inflation-adjust to 1991’s $27,559.55$10,0001991)—a complaint made more absurd by his later boasting about turning down album cover commissions from the Grateful Dead, I believe, for some improbable sum like $848,380.37$100,0001960. Nor is he ashamed of making his wife or the filmmakers drive him around everywhere, pleading that he doesn’t have a driver’s license (still).6 At one point in San Francisco, he is giving a well-rehearsed rant to a young journalist about how much he hates American culture like rap music, and her face is almost rigid trying to not show her disgust; as usual, Crumb is oblivious. (He had previously alienated her by, when she described how shocked she had been to read some of his comics as a kid and asked him how he could justify making them, blowing her off with some excuse like not being meant for kids.)

Crumb’s long-time friend (and fellow band-mate), documentary director Terry Zwigoff, gives him plenty of rope to hang himself.7

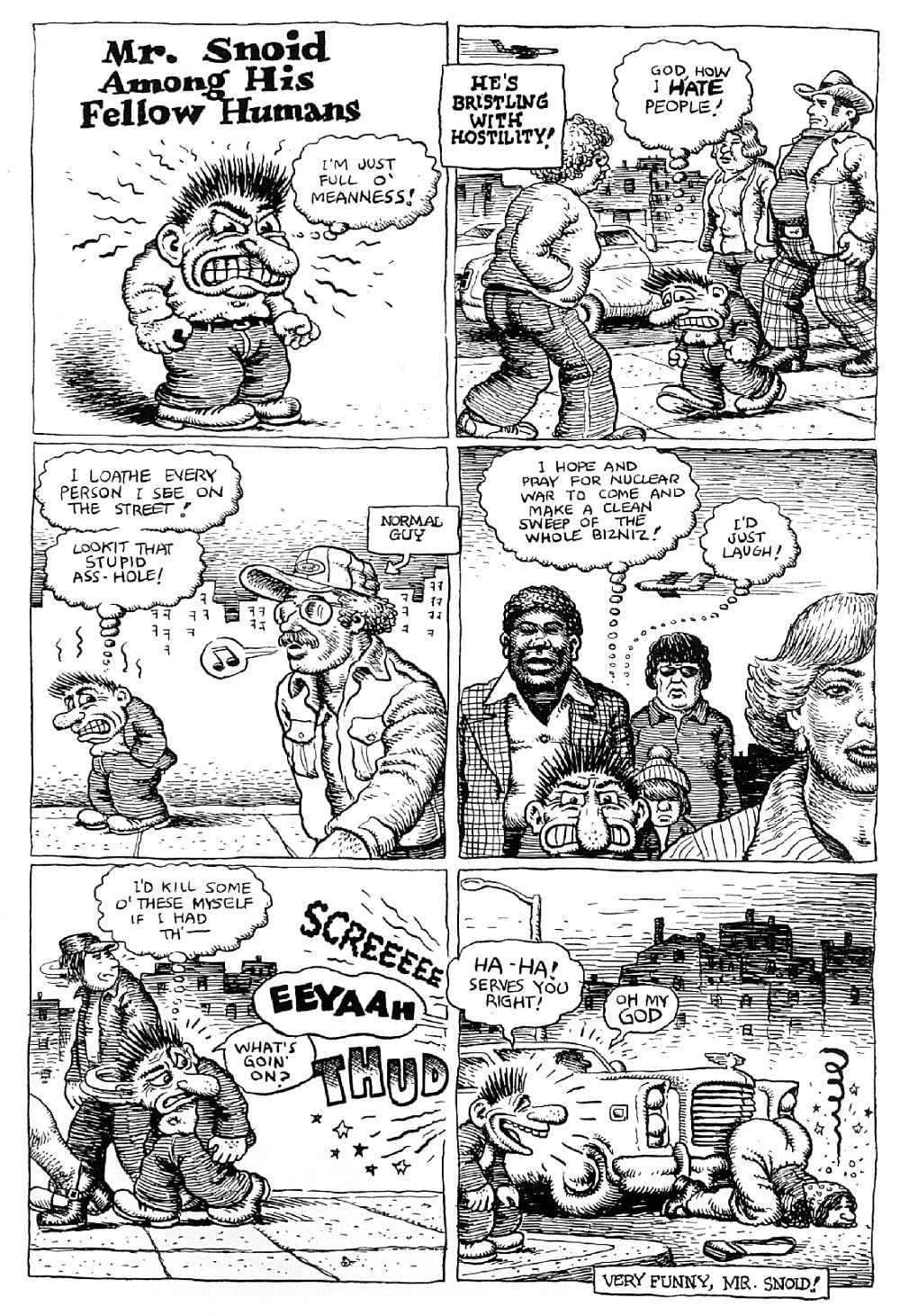

Particularly striking is periodic pans over his incessant sketching in his sketchbooks, which pointedly show how the real world is reflected in the fun-house mirror of Crumb World™ (impossible if we only saw the final result). For example, he spends time in SF sketching passersby; so we can see how a nice normal guy, who is politely listening to his pretty girlfriend while they have lunch in a cafe, transmutes in Crumb’s envious sketch into a muscle-bound chauvinist—a ‘reality’ which, thanks to the camera, we can see exists solely in Crumb’s head.8

You might wonder how Crumb could be married, how Aline Kominsky-Crumb could tolerate him, but she gets enough airtime that you realize that they are two peas in a pod: she is as neurotically resentful as he is. At one point, complaining about her Californian home, she points at the small houses on the distant hills, which looked much like hers, and says, apparently completely seriously, that they built them just to ruin her view. We also see a neighbor’s boy playing a NES game I recognized as one I enjoyed playing as a kid, and she mocks both as worthless.9

Family Dysfunction

And as the backstory about the Crumb family fills in, it becomes clear that Crumb’s famous “critique of the 1950s American family” is just a critique of his family: there is not a single person in it who doesn’t come off as seriously screwed up. The parents were both screwed up, married each other, and then they had kids who got a double-dose of screwing-up.

It is unclear how well the sisters did, because they are scarcely mentioned (presumably due to their choice to not cooperate, most discussion of them was also cut), but they do not seem to have done too well—WP links an obituary for “Carol Degennaro”, who worked in a public library her whole life and was survived by her 3 cats, and no information about the other sister.

It was the boys who proved most vulnerable. Strikingly, of Robert’s 2 brothers, both of them had extreme mental illness: the older brother, Charles, the tyrant of the children, got the worst of it.

Charles Crumb

How perfectly goddamned delightful it all is, to be sure.

young Charles Crumb’s catchphrase

In adolescence, Charles Crumb became increasingly strange.10.

He became obsessed with drawing cartoons and forcing his siblings to help (spurring Robert’s own interest in drawing), developing a pedophilic obsession with a child actor in a Treasure Island movie, eventually losing even his drawing ability to graphomania (see Comiclopedia for photographs), followed by inability to go out or work (holding down only one job briefly in his life), and eventually schizophrenic psychosis that hospitalized him (apparently after a suicide attempt drinking furniture polish) and left him with a heavy burden of psychiatric drugs that made him fat, sleepy, and sex-less, forced to live with his mother his entire life. His cartoons were in a unique ‘circular’ or ‘rubber tire’ style (as if the Michelin tire man drew comics), but he says he hasn’t drawn in decades by the interview.

He bluntly confesses this all when Robert visits him, and though Robert tries to downplay it, is clearly depressed that his entire life has been a complete and total waste, with only one thing to be proud of: that he didn’t rape any boys. The conversations are interrupted by the harrying mother, herself in terrible physical shape, and inevitably reminiscent of Hitchcock’s Psycho.

It is not surprising that he committed suicide in February 199234ya. (“According to Robert Crumb, the first thing his mother said to him was: ‘How could he do this to me‽’…After Charles died, his mother destroyed all his artwork, writings, journals and comics.”)

Maxon Crumb

The youngest brother, Maxon, is almost as peculiar.

According to him, he early in puberty began developing epilepsy closely tied to any kind of sexual stimulation. He describes his obsessive stalking of women and rape fantasies, and was eventually hospitalized after yanking down the shorts of a particularly attractive young Jewish woman in public, at the counter of a store, while in a sort of horny epileptic trance. The hospitalization and drugs apparently helped stop him from escalating to rape.

At the time of Robert & the documentary crew visiting him, he had been living in a SF single-occupancy hotel (of the sorts which scarcely now exist, possibly rent-stabilized), supporting himself by begging in the streets while painting, meditating, and practicing bizarre ascetic practices, while starving himself down to a skeleton. (Ironically, while he looks like he is at death’s door in Crumb, he is still alive as of 2024; while several other people, who looked far healthier, like Jesse Crumb, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, or Charles Crumb, have all since pre-deceased him.)

His meditating is ordinary enough, even if nail bed meditation is hardcore, but what boggled me the most was his description of how he had to clean himself—demonstrating it on camera—by swallowing a few dozen meters of cotton rope, to pass out the long way. I had never heard of this and wasn’t sure he hadn’t made it up, but “dhauti” apparently is real (just obscure).

The paintings strike me as only mildly interesting (sort of a Gustav Klimt/Robert Crumb mix), but he appears to have enjoyed a modicum of success as an artist since Crumb, perhaps boosted by the success of the documentary; and whether his asceticism helps his mental illness or not, Maxon found a way to live better than Charles did.

Robert Crumb

So, that brings us to the middle brother, Robert Crumb himself.

Crumb does not describe any major symptoms of mental illness (aside from being a horrible little rat). His personality, obsessiveness, rape fantasies etc. are incomparable to the problems of Charles & Maxon, even if they are what we expect from the high heritability of mental illnesses & family-level correlations.11 So, what is Crumb’s deal? Why is he the famous artist, and not, say, Maxon?

Crumb tells us: forced to draw so much by Charles initially, he liked it, and kept at it, honing his skills until he was a good draftsman, and became a comic artist; he moved to San Francisco and participated in the Haight-Ashbury hippy scene (despite his general contempt for everyone, which included them).

But that was just the start. He was an ordinary artist at that point.

LSD

What made Crumb Crumb was simple, and abruptly explained by Crumb in one scene: one day during his SF period, he crumbed up his brain by taking LSD12, as was the fashion at the time (c. 196561ya), and had a bad trip that left him almost artistically crippled, capable of drawing only—he doesn’t use this terminology and I don’t think he realizes the connection—what are clearly “tadpole people”. Once he recovered half a year later, he discovered he had gained (or perhaps, lost) the ability to just draw “stream of consciousness” style: “…somehow LSD had liberated me in this way that allowed me to put it [comic art] down [on paper] and not worry about what it meant.”

That is his secret: everything just comes out on its own, as automatic writing. You could do this too—spend a few years learning to draw owls, and then LSD is not hard to get, even in large quantities.

The only catch is that you’ll probably go crazy and become a rapist or commit suicide instead of turning into a rich famous artist. (Crumb himself does not advise trying it.)

So you might say, Crumb is what you get when you take an artist with very good technical skills, who is fairly far out on the schizophrenia spectrum but not too far, and then carefully break open his brain with psychedelics to let the images leak out. Or to put it another way, Crumb is a freak of nature: the human equivalent of a neural net image generator or LLM, almost an idiot savant of drawing.13

Automatic Drawing

By the end of Crumb, after spending 2 hours the company of him and his fans, and seeing countless pieces, I felt the deadliest of reactions to an artist’s life-work: apathy. I had no interest in going and reading any of his old comics. (Maybe watching the Fritz the Cat movie, but that’s it.) Because they’re just one d—n thing after another—there’s no there there.

This explains a lot, like how Crumb’s defenders desperately struggle to defend & interpret the deep messages of his art—oh, it’s like Bruegel!, one says14, or his wife Aline says, his vicious satires of big-thighed women made her feel better about herself!—or his inability to write a plot more than a few pages long or develop any kind of fictional universe, or how it’s always “dream-like”, or how he is always sketching (in an echo of Charles’s graphomania).

All of the lurid rape fantasies, the racist blackface caricatures, the characters and people, it’s just the lower parts of his brain babbling away, and his pen endlessly scratching away to record the samples; and that’s what he’s spent the past 50-odd years doing.15 They don’t mean anything; and if you spend a minute trying to understand a Crumb comic, well, then you’ve spent a minute longer thinking about it than Crumb ever did,16 and you’re overthinking it.

Depth

No wonder the more I looked at the samples of Crumb’s artwork, the less I liked it. In fact, thinking about his artwork has helped me understand what I consider to be bad about AI art: it is the lack of “depth”, in the sense of being able to see more in a work the longer I look at it.

Gene Wolfe remarked that “My definition of good literature is that which can be read by an educated reader, and reread with increased pleasure”. And Wolfe succeeded in this goal with his works like “Suzanne Delage” where after 3 decades, I continue to “reread with increased pleasure” as I become more educated.

Whereas with Crumb’s art… “what you see is what you get”—and all you get, because his work is exhausted in seconds. You look at a face, admire the draftsmanship, and that’s all you get; and you have to move on to the next image semi-randomly juxtaposed next to it on the page. (They might as well all be replaced by a short text prompt in Midjourney: “closeup of fat woman leering, in the style of Robert Crumb, black and white pen”.)

Crumb & AI Art

Just like neural net generated text or images, we are so overwhelmed by the low-order correlations, the pixel to pixel or word to word coherency, that we easily become convinced there must be a there there, because we don’t ever encounter such fluent text or locally coherent images which don’t have any global meaning. The generated samples are parasitic on human samples, which do have multiple levels of structure, and payoffs for thinking about it. But the longer we look at a generated sample, the more we realize that it’s “just one d—n thing after another”, and it adds up to less than the sum of its parts. We put more into it than we get out; it is the artistic equivalent of a scam, or those videos on social media where the gimmick is that it is impossibly blatantly wrong or always looks like it’s about to make sense, to keep you watching and troll a reaction out of you. (It is not even good pornography, derivative as it is of Tijuana bibles.)

It is also no wonder that Crumb was so popular among the hippies and fit in with the psychedelic artwork of the era: the signature feature of that style is that it is packed with meaningless detail, which means nothing, but feels important. (Isn’t it interesting that a false feeling of profundity, insight, and unity is also one of the most striking aspects of the psychedelic experience…?)

Crumb’s LSD-caused art was the perfect fit for an era of LSD-affected readers.

Successors

And perhaps that is why there is no other Robert Crumb.

It was not for lack of trying. Crumb did try to make it a family business: he teaches Jesse Crumb on camera, who attempted to make a career out of it, with only modest success, while struggling with unspecified mental illness (alluded to in Jesse’s review of Crumb, which is rather meta) before dying on New Year’s Eve in a car accident. He also teaches Sophie, who he dotes on in the documentary, to draw; Sophie likewise attempted to make a career out of it, but did not get far, producing a few works before apparently retiring to become a housewife in the French countryside (married to a “construction worker”, and, if you want to believe a certain interviewer, a “heroin addict”).

Legacy

Crumb’s epigones can imitate his draftsmanship and the cross-hatching, yes, but their brains are not broken in the right way to enable stream-of-consciousness; and in any case, the time & place that enabled the Crumb brand is long gone. (Mere prolificness and subversion can’t genuinely shock, when the culture & art being subverted is the subversion of a subversion of something from half a century ago that might have been a parody itself.)

Crumb exists as a brand coasting on hippie fumes, not live art. If Crumb had teleported from the 1960s to today and started posting his art on Twitter as an unknown artist, he would be criticized for merely being another “AI slop” hack—more industrious than most in his LoRA-training and inpainting and touching it up in Photoshop, sure, but not of any note.

There cannot be another Crumb.

Evaluation

So, that is Crumb’s deal: he inherited a fragile psyche, became somewhat randomly obsessed with drawing as his special interest, and then broke his brain with LSD just enough to become an idiot savant of automatic drawing from his subconscious at the exact era in American culture where that could be hailed as the work of genius and make him a millionaire, but because that was all he was, he was unable to develop beyond endless random drawings.

He has done that ever since, with his fans reading into it everything that he is lacking because they cannot imagine that anyone (or anything, one might add) could be so “creative” without it coming from a deep font of ideas & critique.

And that is Crumb in Crumb.