Shiny balls of Mud: William Gibson Looks at Japanese Pursuits of Perfection

Essay on minimalism, otaku, and hikikomori as esthetic choices reflecting an obsessive focus on perfection of a single activity, exemplified by the unusual sculpture form dorodango (hand-rolling mud into colorful spheres).

Transcript prepared from a scan of the original publication; the final quote comes from Gibson’s postscript to the piece collected in his 201214ya anthology Distrust That Particular Flavor (EISBN 9781101559413). All links & footnotes are my insertion.

Shiny Balls of Mud: William Gibson Looks at Japanese Pursuits of Perfection

by William Gibson, TATE, pg108, issue 1, September/October 2002

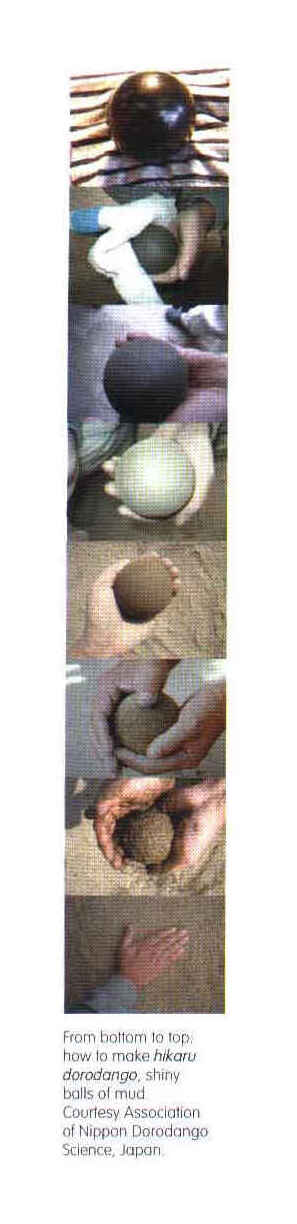

From bottom to top: how to make hikaru dorodango, shiny balls of mud. Courtesy Association of Nippon Dorodango Science, Japan.

Japan, 199630ya: a 19-year-old boy hasn’t been doing well in school. He goes into his room one evening and closes the door.

He only leaves his room when he’s certain that his mother and father are either absent or sleeping.

His mother stands silently before his door for hours, waiting for him to emerge.

He uses the kitchen when he’s sure of his parents’ absence, or the living room, watching television there, or using the computer. He uses the bathroom as well, emptying whatever containers he keeps for this purpose.

She continues to slip his weekly allowance under the door, and assumes that he buys food and other supplies in all-night convenience stores, and from the ubiquitous vending machines.

He’s 25 years old now.

She hasn’t seen him for six years.

When I first visited the Shibuya branch of Tokyu Hands, I was looking for a particular kind of Japanese sink-stopper: a perfectly plain black sphere of rubber, slightly larger than a golf ball and quite a bit heavier, on a length of heavy-duty stainless-steel ball-chain.1

A Vancouver architect had shown me one. He admired the design for its simplicity and functionality: it found the drain on its own, seating itself. I was going to Tokyo for the first time, so he drew a map to enable me to find Tokyu Hands, a store he said he couldn’t quite describe, except that they had these stoppers and much more.

At first I misunderstood the name as Tokyo Hands, but once there I learned that the store was a branch of the Tokyu department store chain. There’s a faux-archaic Deco Asian spire atop the Shibuya store, with a trademark green hand, and I learned to navigate by that, finding my way from Shibuya station.

As the Abercrombie & Fitch of my father’s day was to the well-heeled sport fisherman or hunter of game, Tokyu Hands is to the amateur carpenter, or to people who take exceptionally good care of their shoes, or to those who construct working brass models of Victorian steam tractors.

Tokyu Hands assumes that the customer is very serious about something. If that happens to be shining a pair of shoes, and the customer is sufficiently serious about it, he or she may need the very best German edge-enamel available for the museum-grade weekly restoration of the sides of the soles.

My own delight at this place, an entire department store radiating obsessive-compulsive desire, was immediate and intense. I had stumbled, I felt, upon some core aspect of Japanese culture, and everything I’ve learned since has only confirmed this.

America or England might someday produce a specialist department store combining DIY home-repair with less practical crafts, but it wouldn’t be Tokyu Hands.

Later, I would discover Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s photographs of the interiors of Japanese apartments: ‘cockpit living’2. Everything you own directly before you, constantly available to your gaze. The pleasures of a littered coziness of what to Western eyes seem impossibly tiny spaces, like living in a Joseph Cornell box that’s been through a mild earthquake (and likely it has). Deliberate yet gratuitous collections of things: a bachelor’s apartment wall, stacked floor-to-ceiling with unopened plastic model kits of military vehicles.3

I suspected that these photographs brought me closer to grasping the mystery of the heart of Tokyu Hands, but still it remained just out of cultural reach.

As many as one million Japanese, the majority of them young males, have now retreated into their rooms, some for as little as six months, others for as long as ten years. Forty-one per cent of them withdraw for from one to five years, yet relatively few of them display symptoms of agoraphobia, depression or any other condition that would ordinarily be expected to account for such behavior.

A Japanese parent will not enter a child’s room without permission.

Vending machines in Tokyo constitute a secret city of solitude. Limiting oneself to purchases from vending machines, it is possible to spend entire days in Tokyo without having to make eye contact with another sentient being.

The paradoxical solitude and omnipotence of the otaku, the new century’s ultimate enthusiast: the glory and terror inherent of the absolute narrowing of personal bandwidth.

Hikaru dorodango—shiny balls of mud.

Professor Fumio Kayo of Kyoto University of Education first encountered these enigmatic, glistening spheres in a nursery school in Kyoto in 199927ya.

The dorodango, balls of mud compressed with the hands and painstakingly formed into perfect spheres, became the object of considerable media attention.

The silent young men who must sometimes appear, blinking, in the unaccustomed glare of a Tokyo 7-114 at three in the morning, stocking up on white foam bowls of instant ramen, in their unlaundered, curiously outmoded clothing, are themselves engaged in the creation of dorodango, their chosen material existence itself.

About three inches in diameter, the surface of a completed dorodango glistens with an illusion of depth not unlike that seen in traditional Japanese pottery glazes. A dorodango becomes its maker’s greatest treasure.

Professor Kayo has invented a scale for recording a dorodango’s lustre, with the shiniest rating a ‘five’. It took him 200 attempts and analysis with an electron microscope to duplicate the children’s results and produce an adequately lustrous dorodango.

The genesis of the making of hikaru dorodango remains an absolute mystery.

The floors of Tokyu Hands are haunted for me now with the mysterious, all-encompassing presence of the hikaru dorodango, an artefact of such utter simplicity and perfection that it seems it must be either the first object or the last, something that either instigated the Big Bang or awaits the final precipitous descent into universal silence. At the very end of things waits the hikaru dorodango, a perfect three-inch sphere of mud. At its heart: the unthinkable.

The secret of Tokyu Hands is that everything on offer there inclines, ultimately, to the status, if not the perfection, of hikaru dorodango. The brogues, shined lovingly enough, for long enough, with those meticulously imported shoe-care products, must ultimately become a universe unto themselves, a conceptual sphere of lustrous and infinite depth.

Just as a life, lived silently enough, in sufficient solitude, becomes a different sort of sphere, no less perfect.

Writing for the Tate’s own magazine somehow provided an unusual sense of security, almost of privacy. With the result that I wish this were a novel, somehow.

External Links

“Buzz in Black”, 2005 (on the Buzz Rickson (English) black MA-1 bomber jacket in Pattern Recognition)

“How Japan Copied American Culture and Made it Better: If you’re looking for some of America’s best bourbon, denim and burgers, go to Japan, where designers are re-engineering our culture in loving detail” -(Smithsonian); Ametora: How Japan Saved American Style, 2015

Dorodango.com (Bruce Gardner)