Earth in My Window

Essay by Pop Art artist Takashi Murakami on Japanese society and on WWII infantilizing Japanese culture as revealed by media, anime, and otaku.

- “Earth in My Window”

- Little Boy

- Japanese Film in the 60 Years After the War

- Death and Narrative Merge

- DAICON IV

- The Adult Empire Strikes Back

- Memories of the Atomic Bomb

- An Endless Summer Vacation

- The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World

- Otaku

- Seven-Eleven

- Yuru Chara

- Phantoms in the Brain

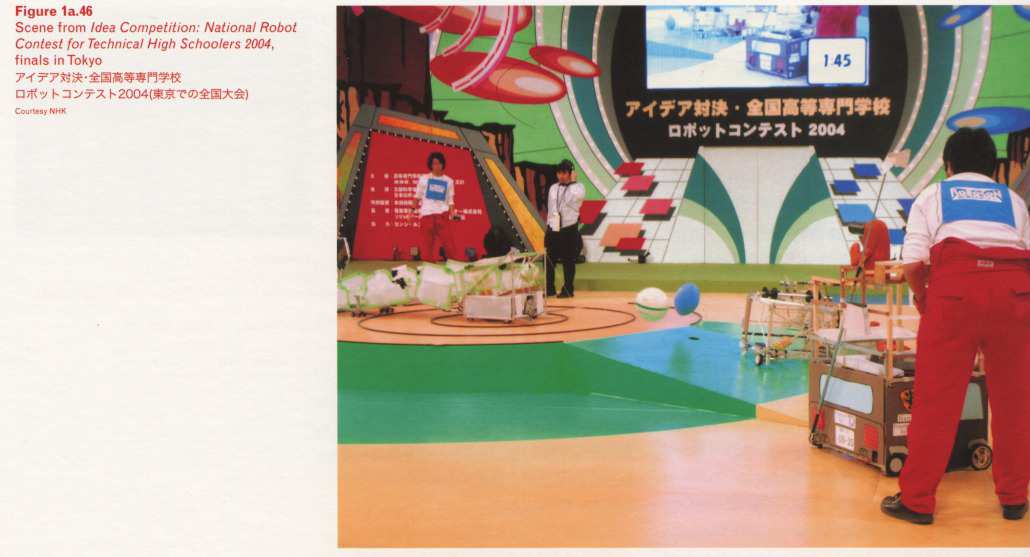

- Robots

- New Type

- Children

- Earth in My Window

- Additional Links

“Earth In My Window” is a long essay by Superflat pop artist Takashi Murakami meditating on post-WWII consumerist Japanese society and on WWII infantilizing Japanese pop culture as revealed by its influences on media, anime, and the otaku subculture.

This transcript has been prepared from a PDF scan of pg98–149 of Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, ed. Murakami, published 2005-05-15, ISBN 0300102852. (See also the transcript of a discussion moderated by Murakami, “Otaku Talk”.)

to hide apparatus like the links, you can use reader-mode ().

“Earth in My Window”

translated by Linda Hoaglund

Little Boy

[pg98–99]

The scent of summer is a kamikaze [divine wind]

A vanished future dreams of tomorrow

Gleaming wings, a terrified profile

Feigning blissful ignorance when we all knowAn historic first, a midsummer memory

Don’t ever forget, proudly beaming

Strutting like a star, can you soar through the big summer sky?That you may never have a second chance

We really hope, we’re all prayingDon’t ever forget, by the way, we’re

Japanese, too, for better or worse

Swing it from your hands, proudly under the big summer skyFarewell to arms, under the midsummer sky

Let’s smile in a corner of the room

Who’s that staring, who’s that hiding there?

With the face of a newborn

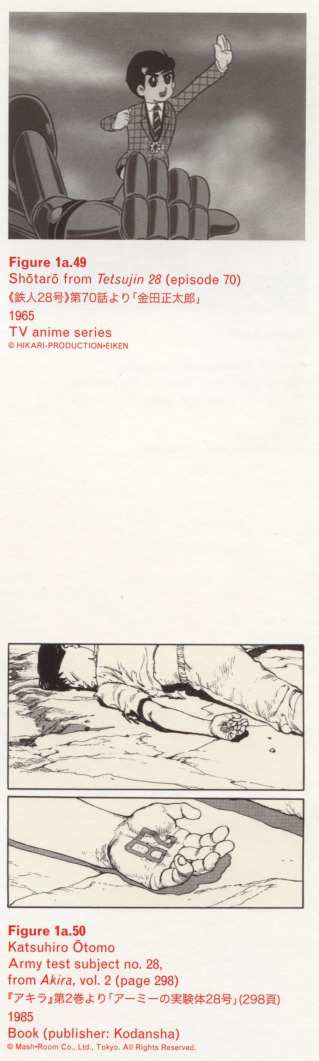

Who are you? What are you? Who are you?(kicell, “Enola Gay”, 200422ya; lyrics and music by Takefumi Tsujimura)

caption right top: Figure 1a.1 Howl and Sophie, from Howl’s Moving Castle 200422ya Animated film; director: Hayao Miyazaki

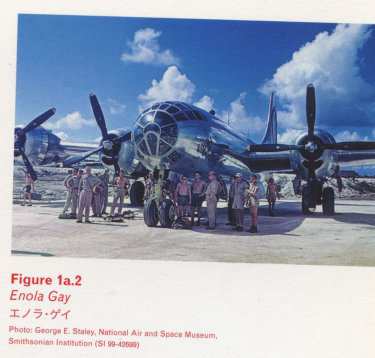

caption right bottom: Figure 1a.2; Enola Gay

[pg100]

Caption left top: Figure 1a.3 George Orwell 1984 (cover) 194977ya Book (publisher: Signet Classic, 199036ya)

On August 6, 194581ya, for the first time in actual warfare, an atomic bomb, nicknamed “Little Boy”, exploded over the city of Hiroshima (pl. 6). Three days later, on August 9, a second atomic bomb, nicknamed “Fat Man”, hit Nagasaki. Together, the two bombs killed more than 210 thousand people; when survivors afflicted by the after-effects of the bombs are included, the figure rises to some 370 thousand. After the tragic explosive-destructive-Whiteout! of the bombs, only burned-out rubble remained: wasteland upon wasteland, utterly vacant land. After the blinding white light, a conflagration of orange… and then, instantaneously, a torrent of pitch-black rubble and mangled body parts actually rained on the people on the ground.

Shortly thereafter, Japan surrendered unconditionally, bringing the fifteen-year Pacific War to an end.

2005. Sixty years after the war. Contemporary Japan is at peace.

But everyone who lives in Japan knows—something is wrong. Still, it’s not worth a second thought. Young girls butchered; piles of cash donations, scattered recklessly on foreign soil; the quest for catharsis through volunteerism; a brazen media prepared to swallow press restrictions in support of economic growth. The doorways of passably comfortable one-room apartments, adorned meaninglessly with amulet stickers from SECOM, a private security company. Safe and sound, hysteria.

Japan may be the future of the world. And now, Japan is Superflat.

From social mores to art and culture, everything is super two-dimensional.

Kawaii (cute) culture has become a living entity that pervades everything. With a population heedless of the cost of embracing immaturity, the nation is in the throes of a dilemma: a preoccupation with anti-aging may conquer not only the human heart, but also the body.

It is a utopian society as fully regulated as the science-fiction world George Orwell envisioned in 1984: comfortable, happy, fashionable—a world nearly devoid of discriminatory impulses. A place for people unable to comprehend the moral coordinates of right and wrong as anything other than a rebus for “I feel good.”

[pg101]

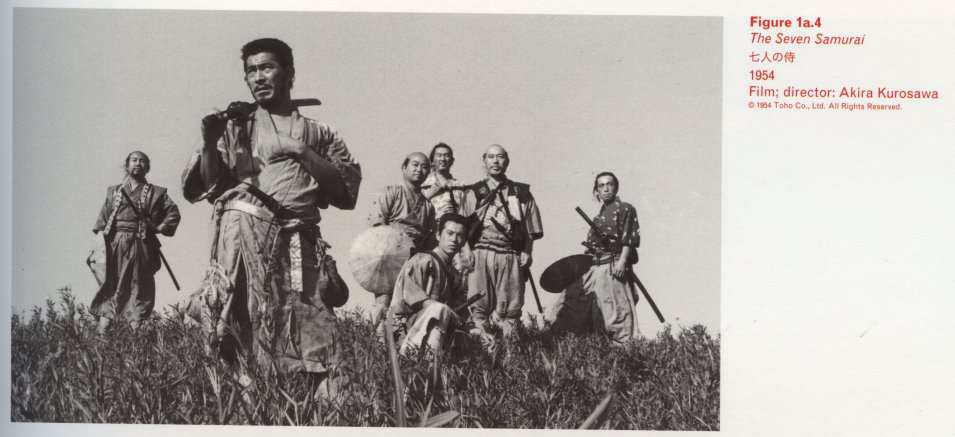

Caption right top: Figure 1a.4 The Seven Samurai 195472ya Film; director: Akira Kurosawa

These monotonous ruins of a nation-state, which arrived on the heels of an American puppet government, have been perfectly realized in the name of capitalism. Those who inhabit this vacant crucible spin in endless, inarticulate circles. In order to solve the puzzle of Japanese culture today, let us view it through individual windows, whether images, songs, or some expression or behavior, as though screening them on a computer. Guided by the fragment of a soul visible at the instant those windows coalesce as one, we will draw the future a little closer.

When kawaii, hetare (loser), and yurui (loose or lethargic) characters smile wanly or stare vacantly, people around the world should recognize a gradually fusing, happy heart. It should be possible to find the kernels of our future by examining how indigenous Japanese imagery and aesthetics changed and accelerated after the war, solidifying into their current forms.

We Japanese still embody “Little Boy”, nicknamed, like the atomic bomb itself, after a nasty childhood taunt.

Japanese Film in the 60 Years After the War

Akira Kurosawa’s undisputed masterpiece, The Seven Samurai (195472ya), a lengthy entertainment running three hours and twenty-seven minutes, was released nine years after the war, and became a record-breaking hit in Japan. Upon its release, long lines snaked outside theaters in Japan, and the film rapidly achieved international popularity; it won the Venice Film Festival’s Silver Lion in the same year. Remade abroad, it has gained countless Japanese and international fans.

[pg102]

Caption left top: Howl and Sophie flying, from Howl’s Moving Castle 200422ya Animated film; director: Hayao Miyazaki

With its relentless pursuit of realism, the film broke new ground among samurai films, dealing with such themes as human resilience, poverty, hunger, pride, loyalty, the futility of Japan’s feudal hierarchy (warriors/peasants/artisans/merchants), and the folly of strife. The world may be a complex place where happiness eludes many, yet humans survive. The Seven Samurai was a hymn to the triumphant right of the peasant or the common man to live.

Although the Japanese had achieved a miraculous postwar revival and no longer scrambled for food, hunger was still an indelible memory, tinged with nostalgia. As they searched for self-respect while acknowledging defeat, The Seven Samurai was no mere costume drama: it was their own struggle. The film defined the Japanese people.

With the changing fortunes of the years, the coordinates of entertainment also shifted.

Now it’s 200521ya. What film defines the Japanese today? Without question, it is Howl’s Moving Castle, released in Japan in late 200422ya.

Hayao Miyazaki, a nationally beloved director whose new works are eagerly anticipated, achieved an unprecedented feat with his previous film, Spirited Away, the highest-grossing film in Japanese screen history.

[pg103]

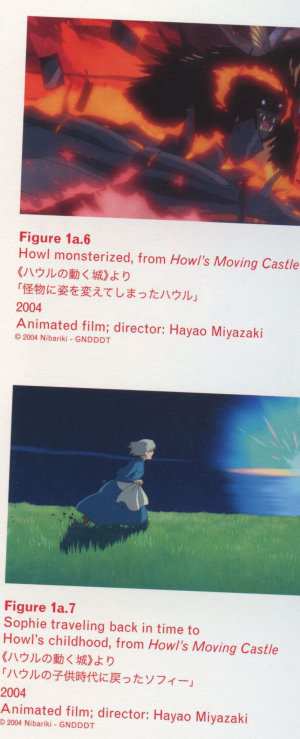

Caption right top: • Figure 1a.6 • Howl monsterized, from Howl’s Moving Castle • 200422ya • Animated film; director: Hayao Miyazaki • Caption right middle: • Figure 1a.7 • Sophie traveling back in time to Howl’s childhood, from Howl’s Moving Castle • 200422ya • Animated film; director: Hayao Miyazaki

His latest film, Howl’s Moving Castle (in current release), is overwhelmingly popular. This film should provide a snapshot of what Japanese people want today. Let us analyze several of its key components.

The young protagonist, Sophie, is eighteen years old. It is the dawn of the twentieth century, an era of unsurpassed nationalism, somewhere in a faintly Alsatian corner of the world. Soldiers of the realm head out to battle. One day, Sophie encounters a beautiful young wizard, Howl. Fleeing from an unknown pursuer, the young man flies up into the sky carrying Sophie, who promptly falls in love with him.

That night, the Witch of the Waste casts a spell on Sophie, transforming her into a ninety-year-old woman. Homeless, Sophie wanders into Howl’s dreaded moving castle, where she takes up residence as an aged housekeeper, disguising her true identity. As Sophie embraces her strange new life in the castle with Howl, his apprentice Markl, and Calcifer (a fire demon who keeps the castle in motion), she opens her heart to them, acknowledging their mutual bonds, and realizes that she is happy. Meanwhile, Howl, who has always pursued a solitary existence, evading his wizardly obligations to engage in war, also changes. Even as he grows haggard from nightly exposure to the fires of war, he has found someone he must protect. By falling in love with Sophie, Howl discovers one cause for which it is worth sacrificing himself to the ravages of war. But the fires of war mercilessly consume even Howl’s humble resolve, and he is quickly reduced to an evil fighting machine.

Surmising that Howl’s condition stems from a youthful obsession with sorcery, Sophie leaps across space and time back to Howl’s childhood, where she must win his heart. She fulfills her goal, the war ends, and Sophie and Howl live happily in the castle.

In the story, Sophie bounces back and forth between eighteen and ninety, aging when she is indecisive and regaining her youthful appearance whenever she makes a choice; she constantly metamorphoses, heedless of the demands of any linear narrative. In the happy final scenes, Sophie is a girl again, yet she retains a shock of white hair.

The film is based on a 1986 novel by Diana Wynne Jones. Although the film remains true to the basic outline of the book, the original plot has been relentlessly altered. Miyazaki’s adaptation is rooted in the [pg104] protagonist’s quest for the meaning of life, which mirrors the same quest of contemporary Japanese. It also incorporates Miyazaki’s corrosive yet genuine struggle through personal traumas during the Pacific War. Gradually, Miyazaki has transformed Wynne Jones’s story into a self-deprecating portrait of himself, concluding that if he must live in a land of complete defeat, which has chosen apolitical involvement in war, he has no choice but to keep making movies.

A Hollywood producer reading the screenplay in advance might well have had misgivings about financing Howl’s mammoth production costs. But Miyazaki has created the ultimate entertainment for present-day Japan, with a powerfully cumulative structure, sequences of intense passion, vivid renderings of a contemporary Japanese ethos, and a voracious appetite for relentless volleys of “messages”. Miyazaki knows better than anyone that the Japanese audience hungers for a narrative structure alien to the logic of American films.

The film has three major themes. First, war is untenable, and no matter how righteous its cause, breaks down the human spirit; the fact that war begins and ends at the capricious whim of a handful of people is cause for despair. In other words, war is ultimately meaningless. Second, no one can live alone. The film stresses our essential need for community, even if it is only a pseudo-family. Third, reality lies somewhere between “aging” and “anti-aging”. The film offers a prescription for the human heart by acknowledging the process of maturation and aging inherent to the span of human life.

All of the problems confronted by the Japanese today are present in Howl’s Moving Castle. Take war, which by all rights should concern us. Even the most obtuse Japanese recognize that we support the war in Iraq. Yet the average person cannot afford to get involved. We feel helpless to change the situation and guilty for living in safety, yet no one takes any action. Then there are the string of recent natural disasters, the murders of young girls and other outrageous crimes, the normalization of young “shut-ins”, and the meaningless continuity of family; finally, our headlong rush toward an aging society, filled with anxiety.

This paradox of an old woman and young girl who occupy one body, this portrayal of the concomitant [pg105] coordinates of age, is about to unfold in the real world. The superimposition of Miyazaki himself, now a white-maned media star, onto this image allows the audience immediate access to hardship, opening them up to sympathy.

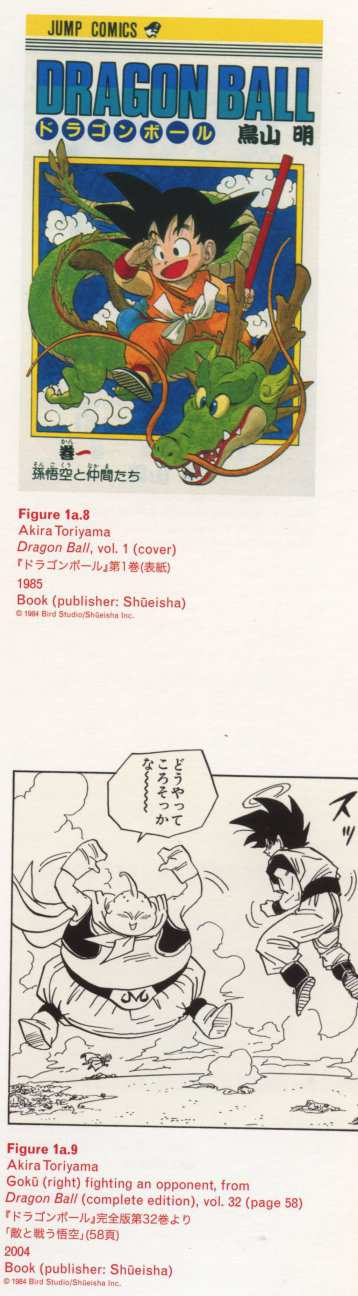

Caption right top: • Figure 1a.8 • Akira Toriyama • Dragon Ball, vol. 1 (cover) • 198541ya • Book (publisher: Shūeisha) • Caption right bottom: • Figure 1a.9 • Akira Toriyama • Gokū (right) fighting an opponent, from Dragon Ball (complete edition), vol. 32 (page 58) • 200422ya • Book (publisher: Shūeisha)

In the fires of war, Howl loses sight of himself and becomes a monster. He can only escape by returning to the past to find himself again. He knows how grim his chances are. Howl’s dilemma is based on Miyazaki’s own childhood experiences of escaping Tokyo and the ravages of war for the countryside during World War II. Miyazaki has candidly discussed the guilt and trauma that he felt over his family’s refusal, as they escaped Tokyo by truck, to help other families begging rides along the way for their children. In addition, he is haunted by the shattered dreams of his youth, when he acted on his belief that ideology could change the world. The heroic sight of Howl, transformed into a kamikaze-like flying fighter amidst a landscape reminiscent of firebombed Tokyo, is rendered real by the fact that Howl indeed has no goal. The gradual transformation of a gentle, charming man into a demon as he is dragged into battle may be construed as a powerful protest against the meaningless of war, cloaked in the guise of a children’s fairytale. The Seven Samurai brought relevance through realism to postwar Japanese; Miyazaki achieves empathy with contemporary audiences not by approaching realism (there are no scenes of human death in the film), but by spinning a children’s fantasy. Howl’s Moving Castle responds to the fears of death that beset Japanese, both young and old. The fantastic, nearly religious scene in which Sophie traverses time and space to enter Howl’s childhood foretells our invitation to the netherworld beyond death; it half suggests karmic reincarnation.

Sixty years after the war, the vestigial phantoms that Miyazaki failed to conquer in his youth still trap this filmmaker, goading him to portray the folly of war. And audiences are moved by Miyazaki’s personal dilemma, with which they empathize and find resonance. This is the movie Japan wants now.

Death and Narrative Merge

The catharsis in Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball, the quintessential mainstream manga, is a climax that never ends. Dragon Ball was the engine that drove Shōnen Jump, a weekly teen manga magazine with a circulation [pg106] of 6.5 million.

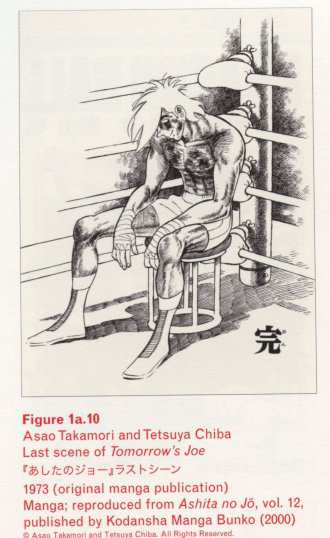

Caption left top: • Figure 1a.10 • Asao Takamori and Tetsuya Chiba • Last scene of Tomorrow’s Joe • 197353ya (original manga publication) • Manga; reproduced from Ashita no Jō, vol. 12, published by Kodansha Manga Bunko (200026ya)

To put this in perspective, Yomiuri Newspaper, Japan’s largest daily, has a circulation of 10 million. Dragon Ball ran to some 520 installments over twelve years 1984–11199531ya. The mightiest popular manga of its day, it had sold over 126 million manga paperbacks by 200026ya. It goes without saying that Dragon Ball spin-offs abound, including an animate TV series, movies, and games. Vast quantities of Dragon Ball characters and merchandise have been produced.

Dragon Ball began with a heartwarming story before shifting into an action series built around the warrior tournaments of the Peerless Martial Arts Association (Tenka Ichi Budōkai). The protagonists fight, win, lose, and learn lessons, then return to fight again in an endless cycle. The tenets of the Shōnen Jump philosophy, “friendship, struggle, and victory”, intensify the moment battling warriors become friends. Dragon Ball then evolved into a battle against aliens intent on world domination, expanding its narrative scale, which increasingly inflates the top warriors and their challengers. The colossal popularity of the series so extended its life that acrobatic devices were continually employed to keep the narrative alive, evading the pitfalls of routine characters and plots. The series eventually went so far as to have protagonist Gokū and the other warriors attain life after death halfway through their stories by means of a miraculous device. Gokū, for example, continues his animate existence by wearing an angel’s halo. Dragon Ball is premised on the preposterous notion that a dead, halo-sporting hero can reduce each of his persistent challengers—from nemesis and super-nemesis to hyper-nemesis—to a pulp. The never-ending cyclical narrative moves forward plausibly, seamlessly, and with great finesse.

In the 1990s, the manga-loving public grew dissatisfied with the essential manga catharsis at the heart of Tomorrow’s Joe or Space Battleship Yamato, in which the final death of the protagonist provides sentimental inspiration. That public demanded a riskier, high-wire narrative to sustain its addiction to weekly manga magazines.

In fact, as legend has it, the creator of Dragon Ball and his readers ended up playing out a game of one-upmanship as extreme—and even as hazardous—as the rigorous thousand-day ascetic practice that an Esoteric Buddhist monk would undergo on the sacred [pg107] Mt. Hiei, nearly sacrificing his own life to attain the revered rank of ajari (Sk: âcârya). The result was the ultimate entertainment of a never-ending loop that defies even death itself.

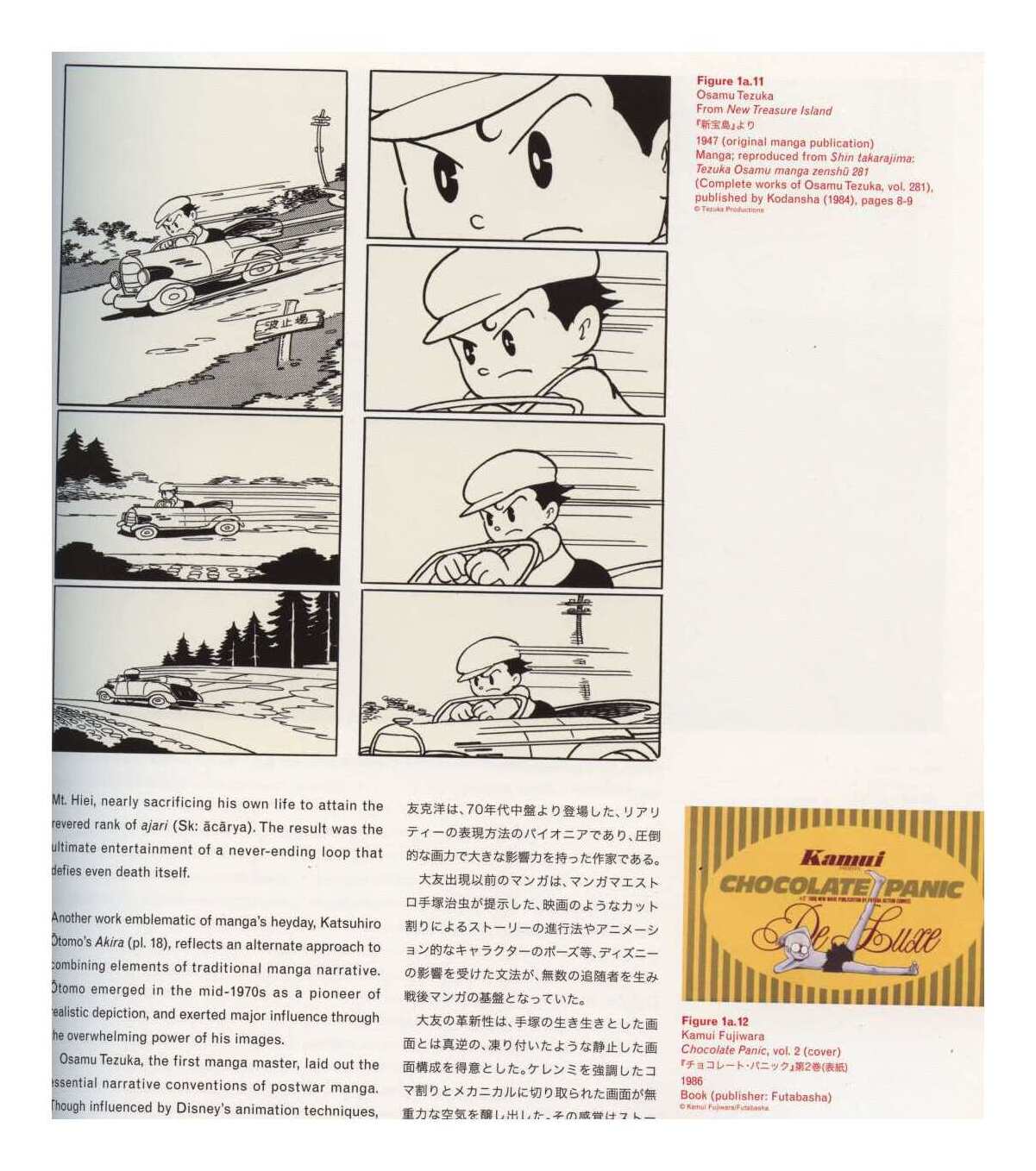

Caption top: • Figure 1a.11 • Osamu Tezuka • From New Treasure Island • 194779ya (original manga publication) • Manga; reproduced from Shin takarajima: Tezuka Osamu manga zenshū 281 (Complete works of Osamu Tezuka, vol. 281), published by Kodansha (198442ya), pages 8–9 • Caption right bottom: • Figure 1a.12 • Kamui Fujiwara • Chocolate Panic, vol. 2 (cover) • 198640ya • Book (publisher: Futabasha)

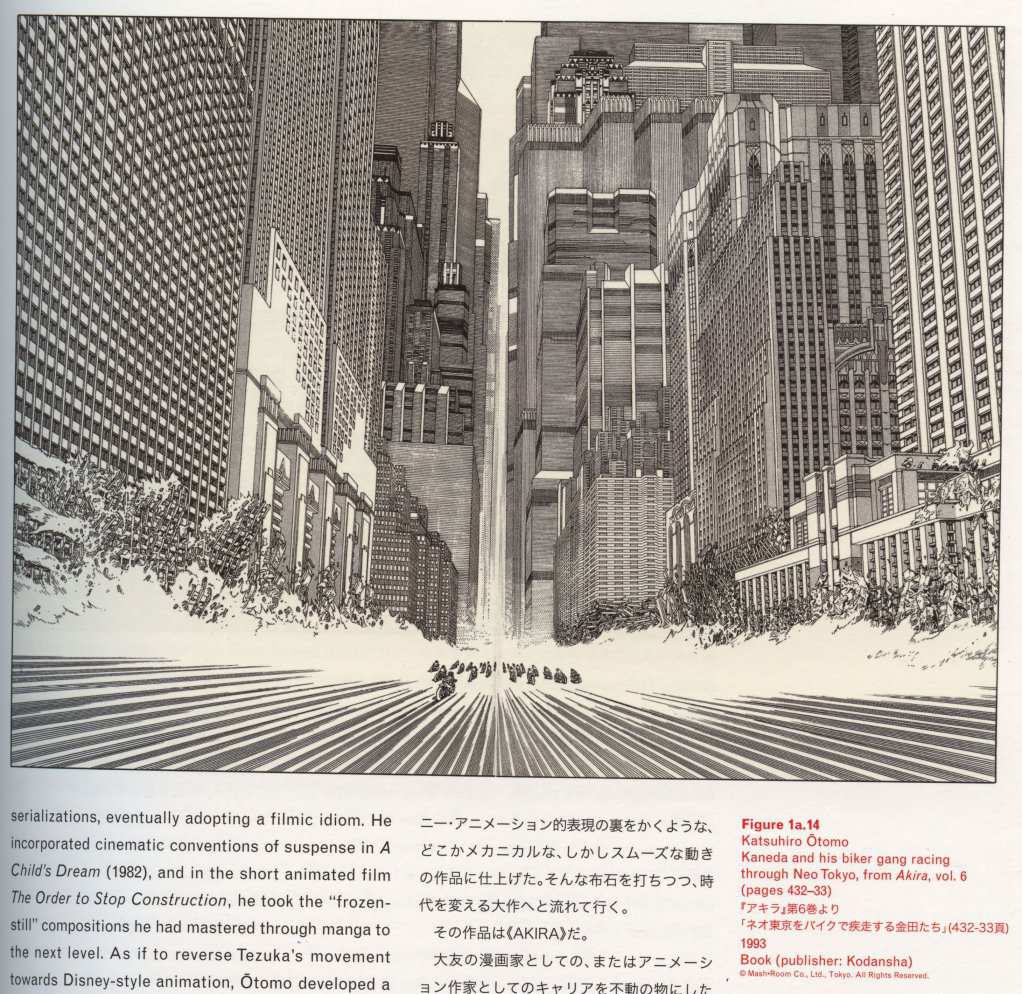

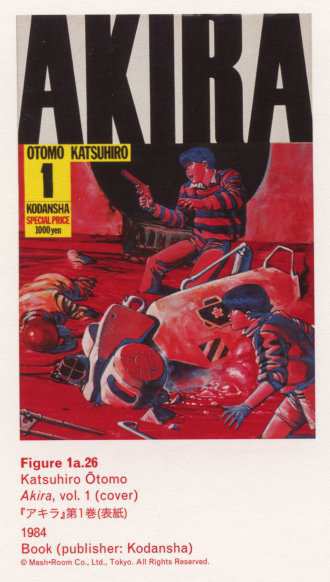

Another work emblematic of manga’s heyday, Katsuhiro Ōtomo’s Akira (pl. 18), reflects an alternate approach to combining elements of traditional manga narrative. Ōtomo emerged in the mid-1970s as a pioneer of realistic depiction, and exerted major influence through the overwhelming power of his images.

Osamu Tezuka, the first manga master, laid out the essential narrative conventions of postwar manga. Though influenced by Disney’s animation techniques, Tezuka devised his own manga grammar, employing a progression of film-like shot breakdowns and character [pg108] poses. His approach drew many followers, creating the foundation for postwar manga.

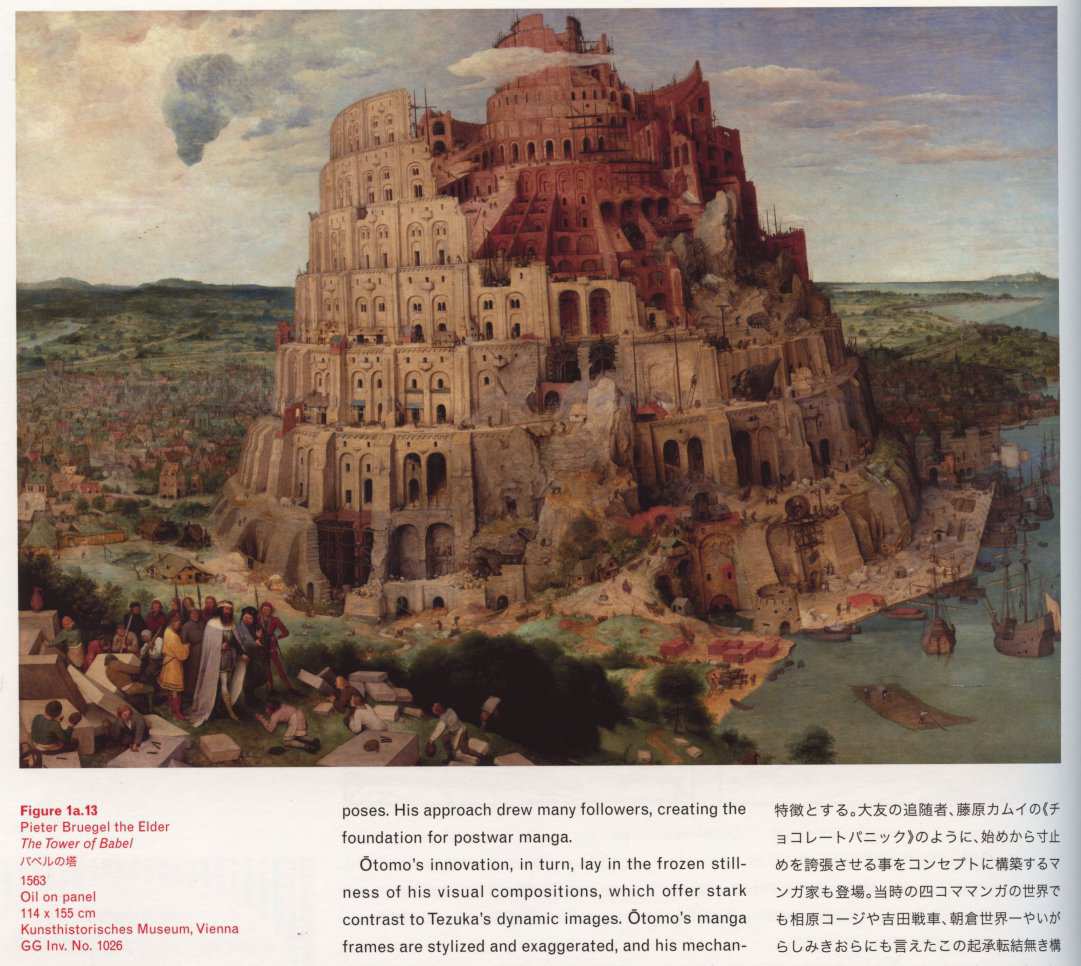

Caption left: • Figure 1a.13 • Pieter Bruegel the Elder • The Tower of Babel • 1563463ya • Oil on panel • 114

Ōtomo’s innovation, in turn, lay in the frozen stillness of his visual compositions, which offer stark contrast to Tezuka’s dynamic images. Ōtomo’s manga frames are stylized an exaggerated, and his mechanically clipped images create a weightless atmosphere. His narratives echo this quality: there’s never a final payoff. They’re anecdotal feints, always sidestepping any denouement. Other manga artists, such as Kamui Fujiwara, the Ōtomo devotee behind Chocolate Panic, began to premise their work on an exaggerated failure to deliver a finale. In the world of four-frame manga, the trend toward a non-narrative structure—found in the work of Kōji Aihara, Sensha Yoshida, Sekaiichi Asakura, and Mikio Igarashi—may be construed as a response to an extreme realism. Ōtomo, one of the pioneers of this technique, abandoned it after several [pg109] serializations, eventually adopting a filmic idiom. He incorporated cinematic conventions of suspense in A Child’s Dream (198244ya), and in the short animated film The Order to Stop Construction, he took the “frozen-still” compositions he had mastered through manga to the next level. As if to reverse Tezuka’s movement towards Disney-style animation, Ōtomo developed a vaguely mechanical yet supple animation technique. With these deliberate strategies his career evolved, heading towards the epic film that would define an era.

Caption left bottom: • Katsuhiro Ōtomo • Kaneda and his biker gang racing through Neo Tokyo, from Akira, vol. 6 • 199333ya • Book (publisher: Kodansha)

This film was Akira.

Akira set Ōtomo’s career as a manga creator and an animator in stone. During the nine-year period over which he serialized the manga, he also adapted it as an animated feature film. In an era permeated by the looming end of the century, Ōtomo, entranced by the notion of the death of narrative, set out to resurrect epic storytelling. Pushing the limits of his visual [pg110] genius, Ōtomo rendered an exploding city in infinite detail. He captured the very apocalypse of postwar Japan with a force akin to that of Pieter Bruegel’s The Tower of Babel. Choosing “post-apocalyptic human awakening” as his theme, Ōtomo employed every experiment and innovation in the service of bringing his film to the zenith of Japanese animation. Inevitably, given this theme, he wound up with a final scene reminiscent of Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

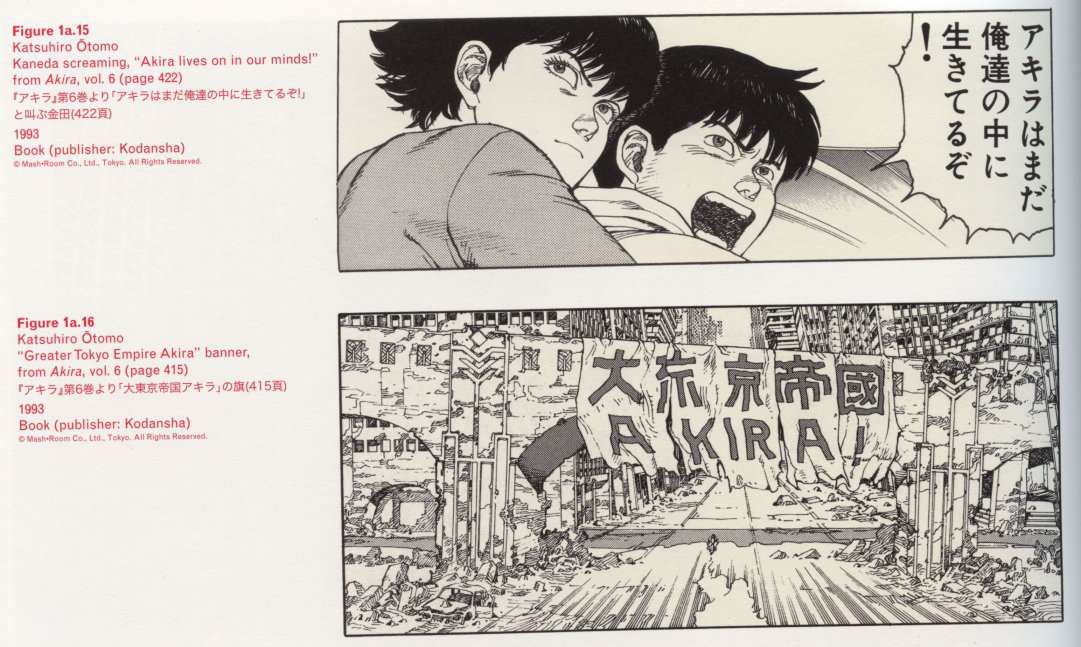

Caption left top: • Katsuhiro Ōtomo • Kaneda screaming, “Akira lives on in our minds!” • from Akira, vol. 6 (page 422) • 199333ya • Book (publisher: Kodansha) • Caption left middle: • Katsuhiro Ōtomo • “Greater Tokyo Empire Akira” banner, from Akira, vol. 6 (page 415) • 199333ya • Book (publisher: Kodansha)

Once the animation production was winding down and Ōtomo began writing the final manga chapter, his theme shifted. It was this shift that made Akira, the serial manga, so revolutionary.

According to prevailing wisdom, Tezuka’s manga is semiotically structured, with characters acting as signifiers to guide narrative. Ōtomo’s work, in which each frame is an individual image, rejected that approach. Ōtomo defined a method in which it is the characters that cement the construction of their world, even as they guide the narrative. And he added another element using manga to critique manga. Instead of defining a closed narrative circle, he strove [pg111] to devise a “meta-manga”.

Let us consider the ending of Akira, volume 6. First, Ōtomo closes the narrative cycle.

United Nations forces have arrived amid the evident destruction of Neo Tokyo soon after Akira’s explosion, prompting Kaneda to scream,

“Take your guns and get the hell out of our country!”

“We’ll keep all the damned aid you’ve brought. But anything beyond that, and you’re interfering with sovereign affairs.”

“Akira lives on in our minds!”

A cry for freedom from a defeated Japan, its own constitution legislated by another nation after the war.

Don’t touch me, let me be independent. We don’t need your U.N. or any other help. The image of Kaneda and the others waving a “Greater Tokyo Empire Akira” flag, with none of the conviction that accompanied brandishments of the former imperial flag of Japan, seems to mock our current “Japanese Nation of Children”. But this is where the story ends, giving way to layouts that conceal new possibilities for manga.

A few pages before the end, Kaneda and the other protagonists race around ruined skyscrapers on motorbikes, even as the skyscrapers rebuild themselves before our eyes. The city, destroyed by Akira and Tetsuo, noiselessly returns to its former state, rendered in painstaking with Ōtomo’s characteristic realism. The reconstruction of Neo Tokyo’s skyscrapers embodies a movement from dystopia to utopia. The link to Tezuka, who, inspired by Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, penned an eponymous manga and created Astro Boy around a similar theme, appears unexpectedly in these last pages.

Ōtomo paid private homage to Tezuka, placing a personal message to the master next to rubble spray-painted with Akira’s emblem.

By the end of the story, the protagonists’ bid for freedom has become the central theme, and the self-resurrecting buildings form a direct reference to Tezuka’s postwar manga grammar.

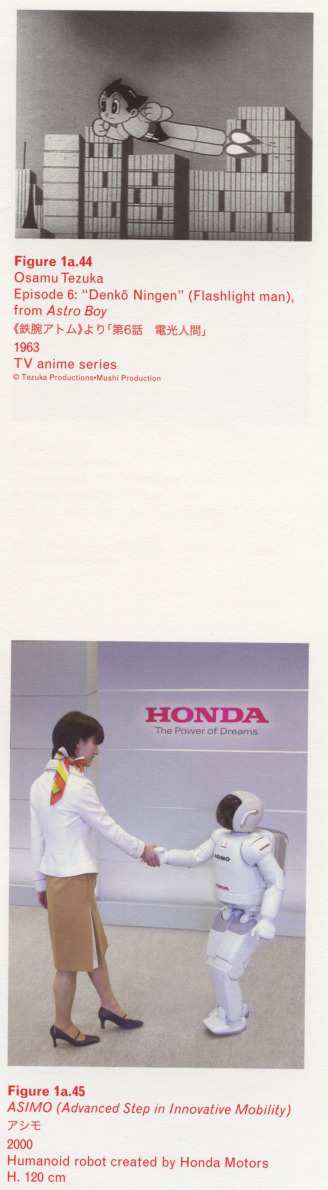

Back in the 1950s, as the Japanese continued to ponder the nation’s defeat, they nonetheless placed their faith in the ultimate cutting-edge energy source: nuclear power. It is no wonder, then, that in Tezuka’s magnum opus, Astro Boy—whose Japanese title, [pg112] Tetsuwan Atomu, literally means “Mighty Atom”—a robot named Atom might have seemed appropriate as a defender of justice who embodied the bright future. To consider that this name is identical to the force of the atomic bomb, and that the bomb dropped on Hiroshima was nicknamed “Little Boy”, is to understand the tortuously twisted road that led from war to recovery. Ōtomo references this journey, critiquing the Shōnen Jump-style popular manga culture of the 1980s in a complete affirmation of his own realistic manga style. Miraculously, he’s pulled it all off simultaneously in a single work, Akira.

Manga occupies a central place in the history of postwar Japanese culture. I am sure Ōtomo believed this. Use manga to critique manga. Finally, Akira, the meta-manga, was finished.

In a sense, this coincided with the emergence of Simulationism in the contemporary art of the late 1980s and early 1990s, and Ōtomo’s motives corresponded to the aspirations of Sherrie Levine and Jeff Koons.

It was a complicated era, when the only way to create reality was to merge narrative and continually generate stories within stories.

We Japanese managed to create a context in which even a corpse, alive in death like Dragon Ball’s halo-adorned Gokū, can meet all challengers. But in this context, the majesty of the living, who accept death as self-evidence, has been discarded.

The decrepit children who appear in Akira accept the futility of life and encounter their own deaths as children, despite their chosen status and supernatural powers; they are exactly like the Japanese today.

DAICON IV

[DAICON III & DAICON IV videos]

DAICON IV Opening Animation (pl. 2) was first shown at the opening ceremony of the 22nd Japan SF Convention held in Osaka in 198343ya. The group that organized the event and created the film consisted primarily of student amateurs. The five-minute 8mm film was a sequel to the group’s debut work, DAICON III Opening Animation, which premiered at the 198145ya conference (also in Osaka). DAICON stands for “Osaka Convention”, using an alternate pronunciation (dai) for the first character in “Osaka”.

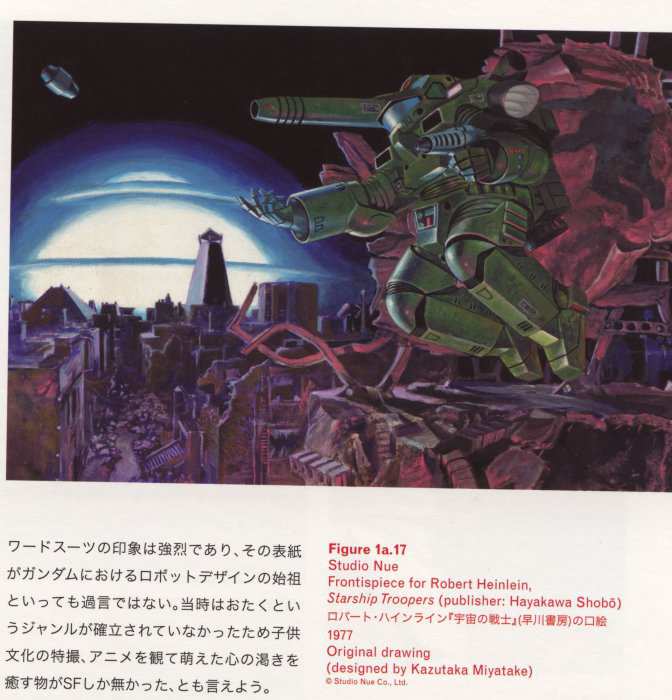

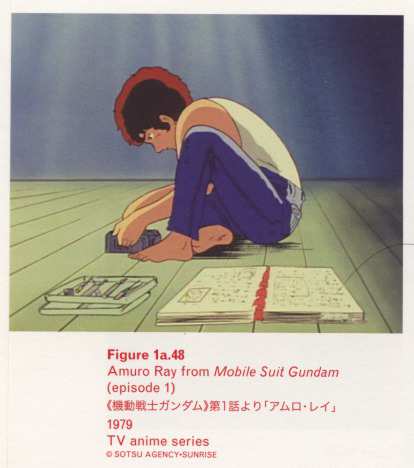

The annual SF (science fiction) convention, inaugurated in 196264ya, remains an event by otaku for otaku, predating the term otaku itself, which did not enter [pg113] public discourse until the late 1980s. Science fiction is intimately linked to otaku culture. The creators of such otaku-favored genres as “robot anime” and tokusatsu (special effects) films drew heavily on science fiction; the anime classic Mobile Suit Gundam, for example, was inspired by Robert Heinlein’s 195967ya novel, Starship Troopers. (In particular, the cover illustration of the “powered suit” created by Studio Nue for the Japanese edition of the book may be considered the direct ancestor of Gundam’s robot design.) Before the full emergence of otaku culture, fans of tokusatsu and anime TV series created for children could further satisfy their appetites only by turning to science fiction.

Caption left: • Figure 1a.17 • Studio Nue • Frontispiece for Robert Heinlein, Starship Troopers (publisher: Hayakawa Shobō) • 197749ya • Original drawing • (designed by Kazutaka Miyatake)

DAICON was their event.

The legendary DAICON animations were created by Toshio Okada, Yasuhiro Takeda, Hideaki Anno, Hiroyuki Yamaga, and Takami Akai (among others), who were then college students in the Osaka area.1 After concluding their activities as amateurs, the group later formed the anime studio Gainax, which made its name with Neon Genesis Evangelion, the bible for contemporary otaku, in 199531ya, twelve years after DAICON IV.

The DAICON animations reveal two characteristics that appeal to otaku. First, they contain abundant references to elements of the subculture that would later be called otaku culture, including Godzilla and Space Battleship Yamato. Second, even though these hand-drawn, 8mm anime films are extremely short at five minutes each, they demonstrate an extraordinary artistic and technical level that exceeds expectations for independent films: not only is the quality of the animation high, but the DAICON animators were able to integrate the picture and the music seamlessly and deploy such sophisticated techniques as multiple exposures far more skillfully than “professionals”. Indeed, the DAICON animators’ relentless pursuit of quality and sophisticated prompted the evolution of science-fiction-based subculture into full-fledged otaku culture.

So, what exactly was DAICON IV Opening Animation?

It’s worth explaining the flow of the film in detail, because the work embodies every otaku paradigm.

Caption left top: • Figure 1a.18 • Science-fiction author Frederick Pohl conversing with conventioneers, from Official After Report of 22nd Japan SF Convention DAICON IV (page 4) • Caption left middle: • Figure 1a.19 • Official After Report of 22nd Japan SF Convention DAICON IV (cover) • August 1, 198442ya • Book (publisher: DAICON IV Committee)

DAICON IV begins with an introduction derived from DAICON III, its forerunner. The soundtrack, performed by Kitarō, who helped define the New Age sound, is very much of its time. The Jet VTOL ship from Ultraman’s Science Patrol slowly descends out of the [pg114] blue sky toward earth, as an elementary-school girl, carrying her randoseru (school backpack), observes the scene from behind a tree. Two patrol members emerge from the ship. They offer the girl a cup of water and ask her to deliver it to DAICON. Bowing, the girl races away, but Punk Dragon blocks her path. He challenges a “powered suit” from Starship Troopers and the battle abruptly begins. The girl tosses the powered suit aside, whereupon Gomora rises from the earth. Using a booster concealed in her backpack, the girl flies up into the sky, with the powered suit in hot pursuit. They continue their battle in midair. A blow from the powered suit sends the girl plummeting to earth, imperiling her precious cup of water. At the last moment, she has a vision of the Science Patrol and regains consciousness. She snatches the cup just before it crashes to the ground, saving the water. Resuming her battle with the powered suit, she catches one of its missiles and hurls it right back at him; a huge explosion ensues. Just then, Godzilla appears. With King Ghidorah and Gamera chasing her, the girl flies through the air with her jet-propelled backpack. The Star Destroyer and an Imperial Scout from Star Wars cross the background. Reaching into her backpack the girl whips out a bamboo ruler, which magically becomes a lightsaber. After slicing Baltan Seijin in half, the girl launches a massive number of micromissiles from her backpack. Hit by a micromissile, a Maser Tank from the Godzilla movies goes up in flames. The Atragon breaks in two as the Yamato, the Enterprise, an X-Wing, and Daimajin explode in total chaos. The girl pours her cup of water on a shriveled up daikon (Japanese radish), buried in the ground. As the daikon revives, it turns into the spaceship DAICON. Bathed in light, and now wearing a commander’s uniform, the girl boards the ship, where the film’s producers, Toshio Okada and Yasuhiro Takeda, sit at the controls. As the landing gear retracts, DAICON departs for the far reaches of the universe. DAICON III, the introduction, comes to a close.

[pg115]

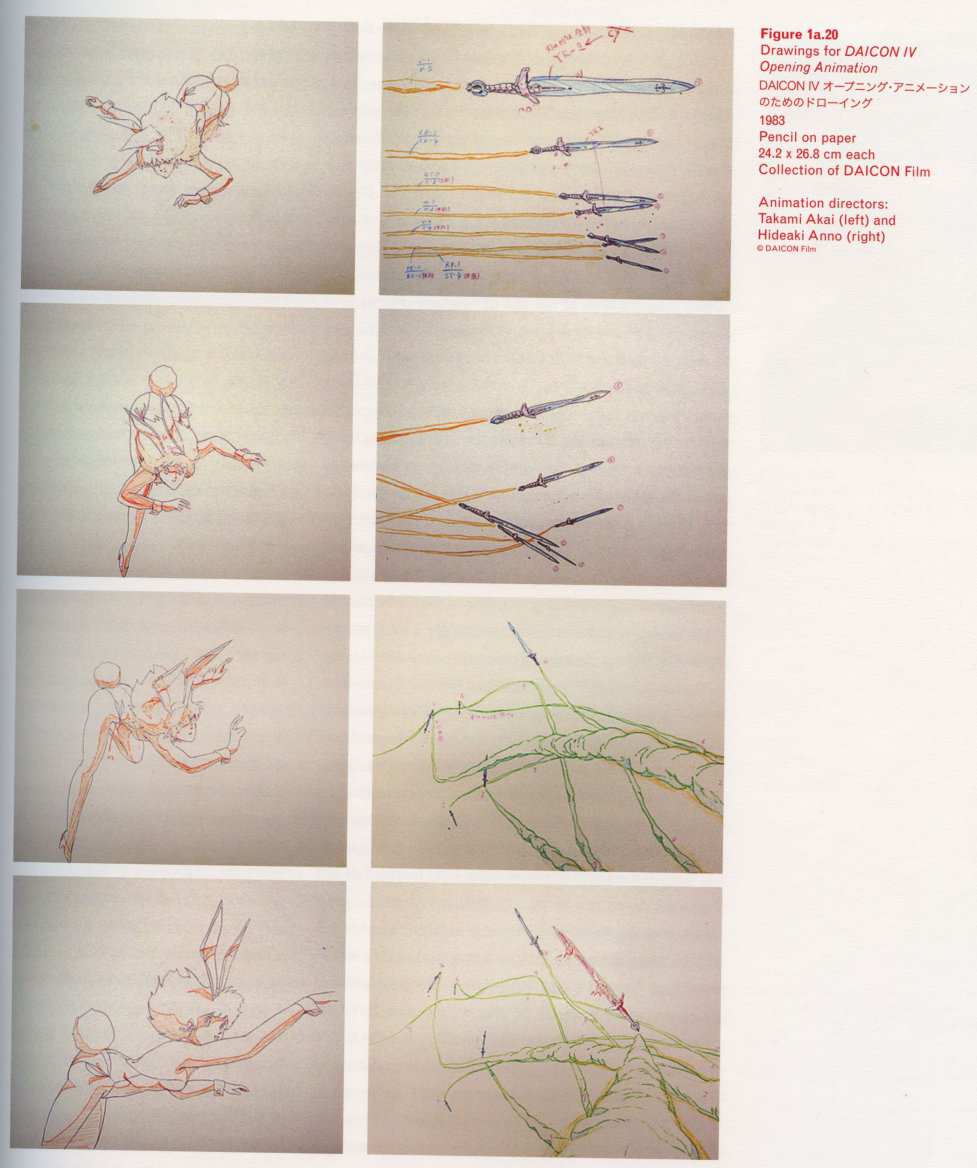

Caption left top: • Drawings for DAICON IV Opening Animation • Pencil on paper • 24.2 × 26.8 cm each • Collection of DAICON Film • Animation directors: • Takami Akai (left) and • Hideaki Anno (right)

The girl with the backpack from the introduction has now grown up into a Bunny Girl. Every last science-fiction/fantasy TV and movie character makes an appearance: Astron, Jamira, Zarab Seijin, King Joe [pg116] Seabozu, Twin Tail, Gesura, Dada, and Saturn. The Bunny Girl jumps into a throng of Metron Seijin. She races past Gyango, Red King, Baltan Seijin, Takkong, Pole Seijin, Z-Ton, Mephilus Seijin, and Seagoras, tossing them all side. Without warning, she’s in a light-saber duel with Darth Vader, while Storm Troopers sit in the background, their legs folded under them. The Death Star is enshrined in one corner. Atop a cliff, aliens who have seized the Discovery from 2001: A Space Odyssey kick up a fuss. The Dynaman robot crushes the girl. When a sword flies at her out of nowhere, Bunny Girl hops on it like a surfer. Just then, Jedi-tei Yū Ida launches into a Japanese comedy routine with C-3PO and Chewbacca in the audience. There’s Nazoh from Gekkō Kamen (Moonlight Mask) and a Pira Seijin with a nametag reading “Tarō the Blaster” (Bakuhatsu Tarō) on his chest. Bunny Girl is still surfing on her sword when she runs into a formation of Ultrahawk 1’s. Then the Yamato and the Arcadia appear, along with an exploding Valkyrie VF from Macross. An awesome midair battle unfolds in an otaku coffee shop (no doubt the filmmakers’ favorite hangout).2 Bunny Girl now travels into an extra-dimensional world. We see Captain America, Robin, Batman, Spider-Man, Wonder Woman…the list goes on. Flying into space are the Thunderbird, a TIE-Fighter, and the Millennium Falcon. Rider, Jumborg A, the Shooting Star, nurses, the giant Ohmu from Nausicaä, Nausicaä herself, Lynne Minmay, Mazinger Z, Kool Seijin, Cutie Honey, and others are there. Having made it through otaku-land, Bunny Girl relinquishes her sword. It splits into seven parts, which fly through the sky spewing flames in seven colors. At the foot of Mt. Fuji are Mogera, the Yamato, Mothra, the Atragon, White Base, and Thunderbird 5. All of a sudden, an atomic-bomb-grade explosion hits an unpopulated city. After the blast, there’s a flurry of cherry-blossom petals. Successive upheavals of the earth give birth to new worlds. As the beam launched by the DAICON traverses the sky, lush greenery sprouts and grows. Robby the Robot, ObaQ, Doraemon, the Five Rangers, and other characters—too many to count—converge: Hakaider, Atman, Maria from Metropolis, Metaluna Mutant, the Robot Gunslinger from Westworld, Captain Dice, Robocon, Derek Wildstar (Susumu Kodai), the Creature, Ming the Merciless, X-Seijin, Lum, Kanegon, Char Aznable, Cobra, Gekkō Kamen, Inspector Zenigata, Mr. Spock, Kemur Seijin, Anne, Bandel Seijin, Superman, [pg117] Soran the Space Boy, Cornelius, Invisible Man, Hell Ambassador, Doruge, Fighters, Boss Borot, the Robot Santohei, Speed Racer (Go Mifune), Big X, Space Ace, Triton, 009, Tetsujin 28, Electric Man, Metalinom, Hack, Bart, Giant Robot, Gaban, V3, Lupin III, Apollo Geist, Bat, Barom One, King Joe. The sun rises, the camera zooms out to the solar system, and The End.

Caption left top: • Figure 1a.21 • Portrait of Hideaki Anno on the cover of Quick Japan, vol. 10 (Ohta Publishing Co., 199630ya)

With every last possible science-fiction (otaku-style) character from around the world—and throughout time—present and accounted for3, the film is obviously a mammoth labor of love. By stuffing their film with all of the beloved creatures that inspired them, the creators displayed a level of passion incommensurate with a work created as the opening event of an amateur competition. There is the thrill of navigating the border between parody and art. More than twenty years after the original screening, this film deserves renewed respect for the energy involved in fashioning a work of such astounding perfection. And yet, as if this achievement were not sufficient in itself, in the last scene of DAICON IV Opening Animation, the fundamental metaphor for any Japanese creator, the atomic bomb—our symbol of “destruction and rebirth”—explodes in an unexpected way.

After the sequence in which Bunny Girl flies around tirelessly, everything is destroyed by (what can only be construed as) an atomic bomb. In the ensuing whirlwind, petals from Japan’s national flower, the cherry blossom, engulf everything in a blast of pink; the streets become scorched earth, mountains are burnt bare, and the whole world becomes a wasteland. Amidst this devastation, Spaceship DAICON, symbolizing otaku, floats in midair emitting a powerful beam—the beam of science-fiction fans. The world revives, giant trees rise in a flash, and Mother Earth is once again bedecked in green. Characters from the world of science fiction gather on the restored planet to celebrate.

In accordance with the rubrics of otaku taste, all of the characters are happy, their chests puffed up proudly at the light of hope. Characters who have never occupied the same screen gradually interact with each other and assemble in the final mob scene—a perfect encapsulation of the science-fiction conference’s message.

In this film, the animators discovered an affirmation behind total annihilation that had nothing to do with [pg118] the politics or ideology of the atomic bomb. This is why they were able to portray the end of the world, without hesitation, as a kind of revolution, and follow it with a “blizzard” of cherry-blossom petals. Hideaki Anno, who later directed Neon Genesis Evangelion, created the explosion scene, and it is almost painful to watch his pathological obsession with it, as an atomic whirlwind destroys the city.

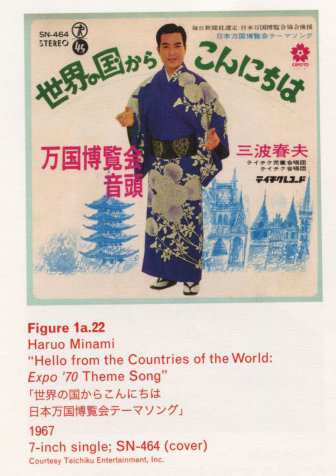

Caption left top: • Figure 1a.22 • Haruo Minami • “Hello from the Countries of the World: Expo ’70 Theme Song” • 196759ya • 7-inch single; SN-464 (cover)

At first glance, this scenario for Japan’s recovery from an atomic bomb seems offhand, but the creators’ compelling message is deeply felt in the urgency of the production values. In a way, otaku sensibilities have much in common with those of American hippies in the 1970s. A lifestyle that seems to turn its back on the world is founded on a nearly groundless obsession with peace and happiness, tremendous curiosity for the internal world of the self, extreme sentimentality, and keen sensitivity, all of which contribute to futuristic creation.

The fact that Japan’s IT industry is built on otaku is also significant, as it suggests a parallel between the hippie movement and otaku culture. One indication of the filmmakers’ obsession with quality and concept was their use of a then-rare personal computer, which enabled them to calculate planetary orbits and thus design the solar system that appears in the last scene. The complexity of this design process offers further evidence of the filmmakers’ obsession with realism.

Surprisingly, it turns out that the ultimate dream of otaku aesthetics, scrupulous yet fanatically obsessed with reality, is a happy party, a peaceful festival.

The Adult Empire Strikes Back

Hello, hello, from the Western countries

Hello, hello, from the Eastern countries

Hello, hello, people from all over the world

Hello, hello, in the land of cherry blossoms

Say hello in 1970

Hello, hello, let’s shake handsHello, hello, to the realm of the moon4

Hello, hello, we fly away from earth

Hello, hello, the dreams of the world

Hello, hello, on a green hill

Say hello in 1970

Hello, hello, let’s shake hands

[pg119]

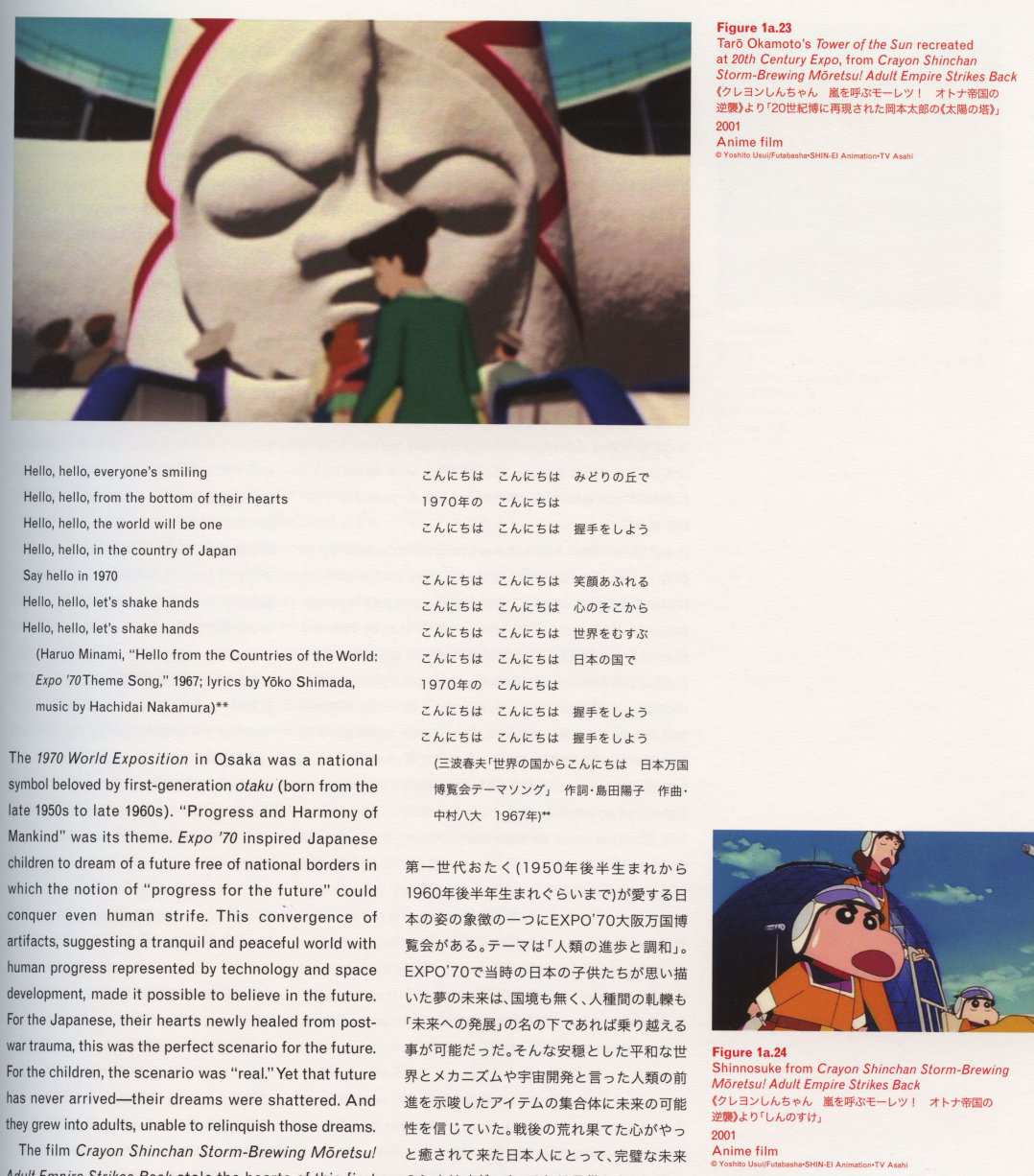

Caption left top: • Figure 1a.23 • Tarō Okamato’s Tower of the Sun recreated at 20th Century Expo, from Crayon Shinchan Storm-Brewing Mōretsu! Adult Empire Strikes Back • 200125ya • Anime film

Caption left bottom: • Figure 1a.24 • Shinnosuke from Crayon Shinchan Storm-Brewing Mōretsu! Adult Empire Strikes Back • 200125ya • Anime film

Hello, hello, everyone’s smiling

Hello, hello, from the bottom of their hearts

Hello, hello, the world will be one

Hello, hello, in the country of Japan

Say hello in 1970

Hello, hello, let’s shake hands

Hello, hello, let’s shake hands(Haruo Minami, “Hello from the Countries of the World: Expo ’70 Theme Song”, 196759ya; lyrics by Yōko Shimada, music by Hachidai Nakamura)

The 1970 World Exposition in Osaka was a national symbol beloved by first-generation otaku (born from the late 1950s to late 1960s). “Progress and Harmony of Mankind” was its theme. Expo ’70 inspired Japanese children to dream of a future free of national borders in which the notion of “progress for the future” could conquer even human strife. This convergence of artifacts, suggesting a tranquil and peaceful world with human progress represented by technology and space development, made it possible to believe in the future. For the Japanese, their hearts newly healed from post-war trauma, this was the perfect scenario for the future. For the children, the scenario was “real”. Yet that future has never arrived—their dreams were shattered. And they grew into adults, unable to relinquish those dreams.

The film Crayon Shinchan Storm-Brewing Mōretsu! Adult Empire Strikes Back stole the hearts of this first otaku generation. The work recreated the atmosphere of Expo ’70 while ironically rendering future-less, [pg120] contemporary Japan in a nutshell.

Let me explain the story.

The Crayon Shinchan franchise originated in the long-lived “shtick” manga series by Yoshito Usui, which ran in Weekly Manga Action (a magazine for young adults) from 199036ya, moving to Monthly Manga Town in 200026ya. Its protagonist, Shinnosuke Nohara, a kindergartner who loves action masks and chocolate snacks, lives in Kasukabe, a suburb in Saitama Prefecture. Shinnosuke’s father, Hiroshi, is a salaryman; his mother, Misae, a housewife; and with the addition of his little sister, Sunflower, the Noharas make up a typical Japanese family. Shinnosuke is a vulgar, rebellious character, distinguished by his precocious taste for attractive women. Although Crayon Shinchan topped the “PTA List of TV Programs Little Children Shouldn’t See”, it became a huge success. Every year brought a new feature film in the series. Adult Empire Strikes Back was directed by Keiichi Hara, who also conceived the original story for the film.

In these films, adults revert to childhood and go to play at 20th Century Expo, a theme park with a striking resemblance to Expo ’70, which has sprouted mysteriously in Kasukabe. The theme park stages famous scenes from classic TV shows, in which anyone can be the hero or heroine while reveling in nostalgia. With the recreation of Expo ’70, Shinnosuke’s parents, Hiroshi and Misae, become captives of their own nostalgia and completely abandon their children. Eventually, the parents give up everything else to stay at 20th Century Expo, and an organization called Yesterday Once More (an obvious nod to the Carpenters) kidnaps the children. The organization is a secret society dedicated to abandoning real, twenty-first-century despair and returning to the “good old twentieth century”. They plan to hoard the nostalgia of the Kasukabe adults until they have enough to push the Nostalgia Meter to its highest levels ever, and then spread Nostalgia Extract throughout Japan to force it back into the twentieth century. When Shinnosuke charges into 20th Century Expo, the scene is a replica of a Shōwa 30s-era (1955–64) street, on the eve of Expo ’70; the scene drips with nostalgia as the adults revel in their forgotten dreams and hopes. They have escaped reality to cling to a hollow past, and relinquished any hope of creating a future. Enduring several falls and a nosebleed, Shinnosuke races up the tower housing the button that controls the release of [pg121] Nostalgia Extract. His trials run live on television, and the sight of Shinnosuke desperately living a real life shocks the adults back to their senses. The level on the Nostalgia Meter plummets, thwarting Yesterday Once More’s plot.

Caption right top: • Figure 1a.25 • Carpenters • Now & Then, including “Yesterday Once More” • 197353ya (original LP release) • CD (cover)

Otaku understand Yesterday Once More, and they find Shinnosuke’s parents compelling. At this point in time, otaku culture spans three generations, including the grandchildren of the first otaku. Whether or not otaku have grandkids, they remain just as dedicated to gathering otaku information and collecting otaku merchandise. But it is also true that the aims of a secret society like Yesterday Once More are empathetic to, if not overtly synchronized with, the terrorist activities of Aum Shinrikyo, the recognized otaku cult that accomplished the 1995 sarin attacks on the Tokyo subway. Otaku have always held excessive belief in their dreams, and have continued to trust that their fantasies would come true. This has only heightened their bitterness upon the betrayal of their dreams. But what is the object of their bitterness? Plain truth dictates that they should direct that bitterness at themselves, a fact that they probably comprehend. Although they won’t plan their own revolution, they won’t give up on the idea of a utopian future. If only—they desperately dream—they were allowed to express their honest feelings in the world of anime. When they indeed find such expression, they heartily applaud it yet sigh in deep resignation, for they know it’s just an empty fantasy. Peculiarly, the stories-within-stories structure of Adult Empire Strikes Back also allows them to see through themselves as revelers in their impossible predicament. In this, we glimpse the reality fraught with despair that awaited otaku after DAICON IV.

Memories of the Atomic Bomb

Behold, a gaze that admits no ray of light

overcome by treachery’s grief

Behold, above our skeptical laughter

a word of rage poised to strike.Every living creature yearns to gnaw our bones,

eyes glint in vengeance, urging us to suicide

God’s creation rebuffs our assimilation

The atmosphere refuses to enfold us [pg122]The gentler our nature the deeper its rages

When that rage has erased

every last kindness, all is for nought

Come, let us sing now, the Ode to Joy

Oh, clouds drifting in a clear blue sky

Bird calls in forest and field

My heart delighted, brimming with joy

Our bright smiling faces exchanging looks

(Kenji Endō, “Ode to Joy”, 197254ya; lyrics by Kenji Endō [last verse by Tōichirō Iwasa], music by Ludwig van Beethoven)

Caption left top: • Figure 1a.26 • Katsuhiro Ōtomo • Akira, vol. 1 (cover) • 198442ya • Book (publisher: Kodansha)

The boom in Japanese science-fiction/fantasy anime was engendered by two works: Space Battleship Yamato and Mobile Suit Gundam (pls. 27, 30). Both works share a narrative genesis in a post-atomic world. And both are fundamental to the birth of otaku culture.

In Space Battleship Yamato, enemy aliens from the Gamilon empire attack the earth. The Gamilons launch a planetary bomb from a great distance, a bomb designed to accelerate radiation contamination and expedite their colonization of the planet. The land is deforested and the oceans run dry.

Mobile Suit Gundam opens with a plan to drop a space colony on the earth. In order to alleviate overpopulation, space colonies have been created at the Lagrange Points, places where the gravitational fields of the earth and the moon are neutralized. One of the colonies, which calls itself the Principality of Zeon, declares its independence from the Earth Federation and declares war. Launching a sneak attack, they take a space colony out of its orbit and drop it onto the earth. Billions die in the attack, both on the space colony and at the terrestrial point of impact, and the earth’s collision with the massive projectile precipitates climate change. Earth, once the mother planet, enters a nuclear winter and becomes all but uninhabitable.

Planetary bombs, or space colonies falling to earth and exploding in blinding white light followed by brilliant red, were all common story elements in the manga and anime of the time. So many of these narratives begin in the catastrophic aftermath of an atomic explosion.

There is a longing for some fundamental human power to awaken when humanity is backed into a corner. Hayao Miyazaki’s original manga and animated [pg123] film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, also begins in a world that has suffered a man-made apocalypse. This is true of Ōtomo’s Akira as well.

Caption right top: • Figure 1a.27 • Fishmans • …Something in the Air, including “Slow Days” • 199630ya • CD (cover)

We feel an abiding sense of righteous indignation at the use of atomic bombs to bring the Pacific War to a close. We level cheap shots at the Japanese government, which placed Japan in that final scenario and then concealed the truth about the bombs’ effects. We feel complex emotions towards the Americans who thrust the terror of nuclear annihilation upon Japan. Added to this is our own cowardly rage for accepting media control as a necessary evil. All of this simmered in the Japanese consciousness as dogma without direction. When these contexts emerged, the message reached its audience in the guise of children’s programming; because reality was portrayed through anime, Japan finally discovered genuine respect for its creators.

In Japanese elementary schools, we do not learn that our country has been managed in an incomplete, tentative fashion ever since the loss of the war. Nor do we seriously grapple with the issue as adults. But everyone recognizes the discomfort generated by this unnatural state of affairs. Japan is well established as a nation unable to address its bad blood. But at least the truth survives, alive and well, in stories told to children. Perhaps it’s fair to say that the unique sympathies we label as otaku were born the moment Japan comprehended the sincerity of these storytellers.

An Endless Summer Vacation

Oh summer sunset past the view in the slow days

Orange days, orange sky in the slow daysThe long, long summer vacation never seems to end

I dream of becoming someone else, with the face of my childhoodOh yeah, one faint memory upon another

Oh yeah, they determine who we areOh summer sunset, orange circle in the sunset sky

That too-smooth color, packed with drama, story told too often

[pg124]

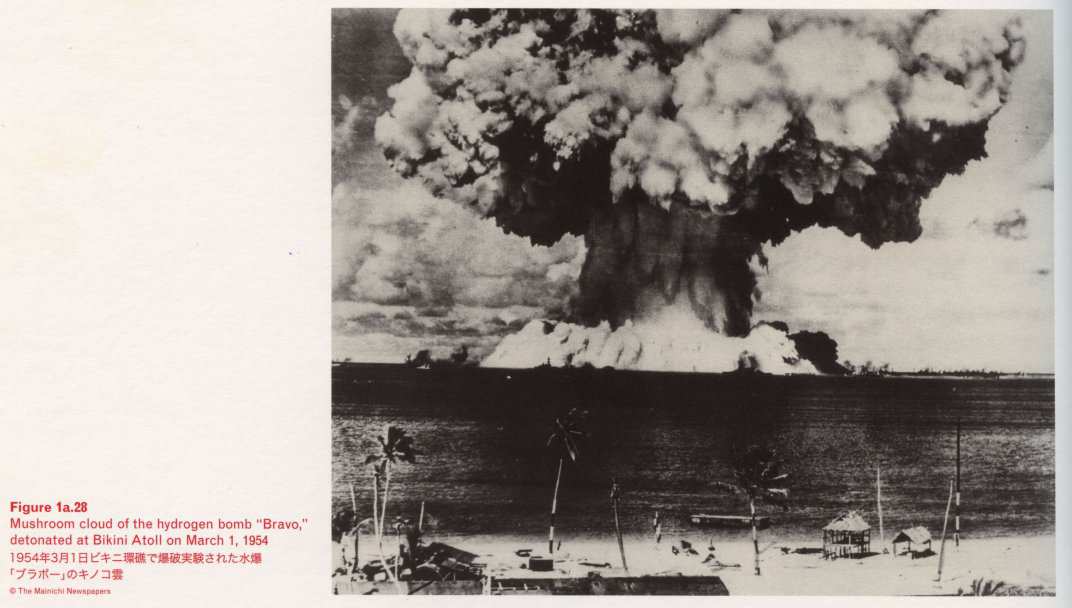

Caption bottom left: • Figure 1a.28 • Mushroom cloud of the hydrogen bomb “Bravo”, detonated at Bikini Atoll on March 1, 1954

Oh yeah, I can’t get to feeling naive

Oh yeah, life’s not that big a dealIn the everyday with nothing lost, we feel fine

From beyond the horizon, the same sound as alwaysSpending these days like I’m bored

Gotta give these days a hard time, too(Fishmans, “Slow Days”, 199630ya; lyrics and music by Shinji Satō)

The first atomic bomb hit on August 6, at the height of summer. The war was over. Summer is the season when the story ends and hell begins. Peace was immediately transformed by a unique sense of time. The blinding white light of the sun and the light of the atomic bomb coalesced, delineating the beginning and end of the narrative.

Postwar Japanese narrative themes jumble summer vacations together with leukemia; many tell stories of doomed love. This still holds true today, as proved by the enormous success of the 200422ya movie Crying Out Love from the Center of the World, based on a novel by Kyōichi Katayama that sold an incredible [pg125] three million copies upon publication. Indeed, the story begins with a heroine who has leukemia.

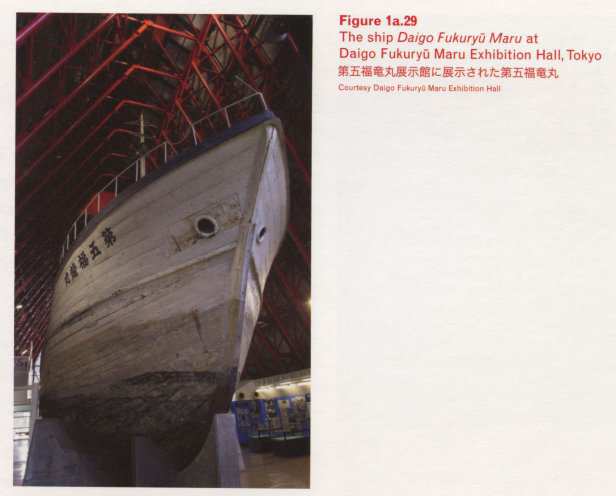

Caption right top: • Figure 1a.29 • The ship Daigo Fukuryū Maru at Daigo Fukuryū Maru Exhibition Hall, Tokyo

The protagonist, Sakutarō (named after the poet Sakutarō Hagiwara), is a high-school junior in a regional city. The story opens with the death of his girlfriend, Aki. Saku and Aki’s friendship goes back to middle school, but they first become romantically involved as sophomores. In the second semester of his junior year, Saku learns that Aki has leukemia. Her parents ask Saku to take their daughter to Australia when she recovers. Saku buys tickets and sneaks Aki out of the hospital on her birthday; they celebrate with a cake on the train to the airport. Aki collapses at the airport, and Saku cries out for help. Aki is rushed back to the hospital, only to die. Several years later, the adult Saku returns to his hometown with his new lover. The high-school campus is rife with memories of Aki. Amid a flurry of cherry blossoms, Saku quietly scatters Aki’s ashes from a glass bottle, which he has kept since her death.

Art critic Noi Sawaragi has studied the frequent appearance of leukemia as a motif in tragic love stories, noting, “It derives from the radioactive fallout in the aftermath of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Marshall Islands hydrogen bomb tests.”

Caption right top: • Figure 1a.30 • Noi Sawaragi • World War and World Fairs (cover)

Sawaragi and I were both born in 196264ya. We were born into the period of Japan’s rapid economic growth, not a time of remarkable social tumult. Our generation coincides with the first otaku generation. (For the record, Sawaragi is not an otaku.) Deeply influenced by TV media at the dawn of the TV age, we have been dubbed “The TV generation”. The transition from black and white to color, JFK’s assassination, the Vietnam War, the moon landing, and archival footage of World War II: we’ve been deluged by these images. And we’ve wondered, why does Japan have a military if we’ve abandoned war? The reason remained in limbo. Because any child, seeing that archival war footage, must have asked his parents, “Why did we lose the war?” “What are the Self Defense Forces?” Our parents would have cited the atomic bombs and disparities in economic power. A military based on equivocation, parents stuck trying to explain the contradictions between the Peace Constitution and the Self Defense Forces: everything in Japan is ambiguous. Our generation swallowed its profound frustration at the rift between reality and the information available in the media, and it festered inside [pg126] us. This created our pathological obsession with reality and realism, as we attempted to identify the source of our frustration.

The leukemia angle and its origins: atomic bombs and hydrogen bomb tests.

I quote the iconic encounter of the fishing boat Daigo Fukuryū Maru with a hydrogen bomb test, so familiar to the Japanese, from Noi Sawaragi’s latest book, World War and World Fairs (Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 200521ya). It illustrates the origins of the never-ending atomic bomb scenario.

On March 1, 195472ya, the Daigo Fukuryū Maru was exposed to radiation from a hydrogen bomb test…

Hoping to compensate for poor fishing off the shores of Midway, the Daigo Fukuryū Maru sped towards the Marshall Islands. On March 1, as the ship pulled in its catch, a ball of fire something like the sun rose in the distance, followed by concussive waves. Rain mixed with particles like white sand fell over the crewmembers as they hurried back to port. These were the “ashes of death”. They invaded the fishermen’s bodies without mercy through the mucous membranes of the yes and nose, contaminating them with radiation from the inside out; on September 23 of that year, the first of the crew members, Aikichi Kuboyama, died. The health of the remaining twenty-three crew members (whose average age was twenty-five at the time) continued to suffer from long-term radiation side effects, and many have already passed away due to liver cancer and other afflictions…

The many hydrogen bombs tested in the Marshall Islands during this era were born of the acceleration of the U.S.-Soviet nuclear test race. In order to generate explosions significantly more powerful than those of the atomic bombs, the United States was already employing “3F Bombs”. These bombs exploded in a three-phase process of fission-fusion-fission, and bomb casings were frequently coated with depleted uranium. “Bravo” (an unforgivable name), a hydrogen bomb that shocked even its creators with its demonic destructive force, was a natural extension of 3F strategies.

Its fifteen-megaton power remains beyond imagination. By some calculations, the total TNT tonnage deployed by both sides over the four-year Japan-U.S. [pg127] War amounted to three megatons. Imagine an explosion five times that powerful unleashed in an instant upon a coral reef protected only by beautiful, emerald green waters. But the terror of Bravo lay not only in its destructive force. The mushroom cloud it generated rose into the stratosphere, scattering its massive radioactive material into the jet stream, where it circulated over the world…

In fact, Japan’s Pacific coastline experienced heavily radioactive rains in Bravo’s wake. In May 195472ya, Japan reported a Geiger count rate of 86 thousand counts per minute per liter of rainwater. (pp. 332–36)

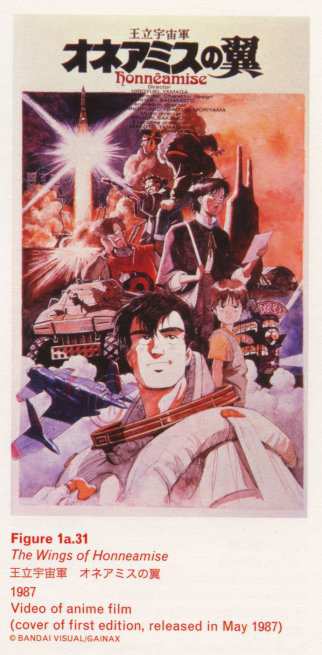

Caption right top: • Figure 1a.31 • The Wings of Honneamise • 198739ya • Video of anime film (cover of first edition, released in May 198739ya)

The Japanese were exposed to radiation from the atomic bomb blasts and then again through hydrogen bomb tests. A blast of pure white light, a summer eternally seared. That orange-colored circle, leukemia, and summer vacation. My own consolation, a still endless summer vacation. The unending pain, the festering, seeks to break out of this dilemma.

The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World

The creators of DAICON IV Opening Animation would come to occupy a central place in the current anime world. The key members of the DAICON group opened the science-fiction store General Products, which was professionally incorporated as Gainax in 198442ya upon production of the feature-length anime The Wings of Honneamise (released in 198739ya). Neon Genesis Evangelion (pl. 33), written and directed by Hideaki Anno and produced by Gainax, is the landmark otaku anime film, which marked the most brilliant moment of otaku subculture.

Evangelion became an explosive hit immediately after the twenty-six original episodes were first broadcast on television in 1995–96. Caught up in the cult-like fervor surrounding the work, fans willingly accepted the controversial and irregular release of the subsequent film: unable to complete it on time, Gainax released an unfinished version to theaters in March 199729ya and released the final version a few months later as a different film. This phenomenon points to the complicit relationship by then formed in the world of animation between the creators and the audience, which recognized Evangelion as an instant entertainment [pg128] classic. The original TV series and the subsequent feature films attracted not only anime fans but also young culture-lovers and anime veterans who had outgrown otaku obsessions. Evangelion is an unsurpassed milestone in the history of otaku culture.

Caption left top: • Figure 1a.32 • Harlan Ellison • The Beast That Shouted Love at the Heart of the World (cover) • 196957ya • Book (publisher: Avon; paperback edition: New American Library, 197452ya)

The story is set in 201511ya, fifteen years after the Second Impact, a deadly cataclysm of global magnitude that originated in Antarctica. The new city of Tokyo 3 is suddenly attacked by “Angels”, unidentified enemies that take various forms including gigantic creatures and a computer virus. NERV, a special U.N. agency charged with fighting the invaders, deploys Evangelions, all-purpose humanoid weapons piloted by three specially chosen fourteen-year-old kids (Shinji, Rei, and Asuka).

A complex amalgam of science fiction and human drama in the form of robot anime, Evangelion showcased Gainax’s skillful animation, along with Anno’s bold use of white-on-black subtitle graphs and speedy, almost subliminal construction of action sequences. In many ways, Evangelion is a meta-otaku film, through which Anno, himself an otaku, strove to transcend the otaku tradition.

While dutifully paying homage to the pop- and otaku-culture landmarks that preceded it, Evangelion pushed its depiction of the psychological and emotional struggles of the young motherless pilots to the extreme. The final scenes were presented in a few different forms and media, including the original TV version, the feature-film version, and finally the DVD version, which combined the preceding two. Each was unfailingly controversial. Especially shocking were the final two episodes of the TV series, which unconventionally mix anime scenes with drawings and video footage. These episodes focus on Shinji, the central character among the pilots, and his painful search for what his life means both as a person and as an Evangelion pilot. With the purposeless Shinji’s interior drama taking center stage, Evangelion is the endpoint of the postwar lineage of otaku favorites—from Godzilla to the Ultra series to Yamato to Gundam—in which hero-figures increasingly question and agonize over their righteous missions to defend the earth and humanity.

The final sequence of the theater version, which incorporated scenes from the TV version in a somewhat confusing manner, constituted the apogee of otaku anime.

[129]

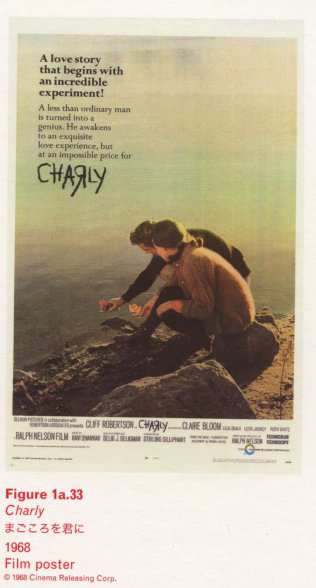

Caption right top: • Charly • 196858ya • Film poster

The title of the final episode of the TV version is “The Beast that Shouted Ai at the Heart of the World”. (The use of katakana, a Japanese syllabic script, for the word ai allows the term to carry the double meaning of homonyms “love” and “I”.) Both the title and concept are borrowed from Harlan Ellison’s eponymous science-fiction novel. In a contest pitting the audience (readers), who are normally on the receiving end of entertainment, against the author’s vision, who can fly higher? How far can the audience both compel and follow the director’s vision? With Evangelion, the director Anno raised a challenge to works that refused to allow audiences any escape from the reality of their own self-consciousness.

The subtitle to the film version’s final sequence also alludes to science fiction, referencing the film Charly (based on Daniel Keyes’s Flowers for Algernon), which was released in Japan as Magokoro o kimi ni (My heart to you). Evangelion also incorporated references and elements, such as the “Spear of Longinus” and “AT (Absolute Terror) Field”, that were freely adapted from Judeo-Christian religious mysticism, psychology, biology, and a wide range of sources. Their juxtaposition with robots and anime provoked widespread speculation and much deeper readings. This simulation-based approach stood Japanese anime’s fundamental disregard for dramatic themes on its head. But ultimately, by arousing sympathy in its audience, it laid bare a true otaku heart.

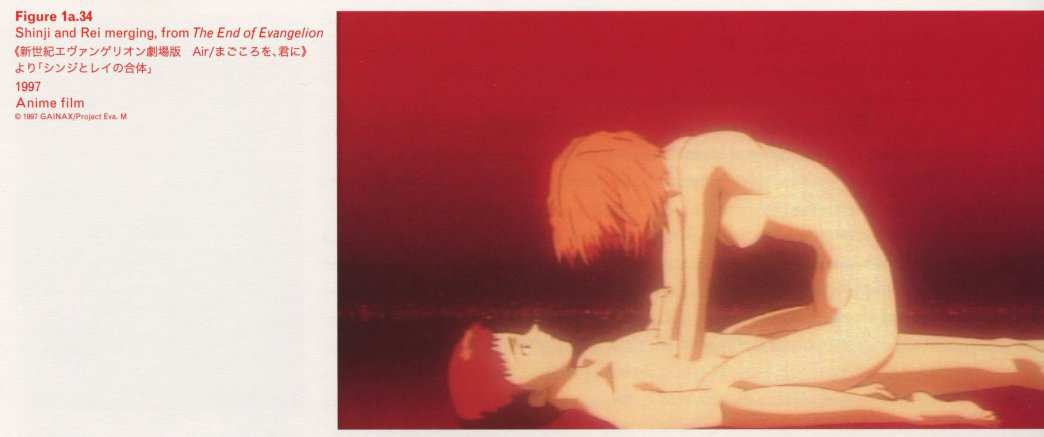

It is the final scene of the film version. When Shinji comes to he has been asleep, naked. Rei, also naked, straddles him, her hand poised to melt and fuse with Shinji’s torso. The Humanity Complementation Program will ensure that all humans liquefy, fuse, and become one. The giant crucified on the cross deep beneath the special agency NERV is recognized as Lilith, and all humans are destined to merge with her, ultimately fusing into one. Lilith was the biblical Adam’s first wife, but the children born of their union, Lilin, were regarded as demons; they represent humanity in the film.

Shinji: “Am I dead?”

Rei: “No, everything’s just becoming one. This is exactly the world you dreamed of.”

Shinji: “But this is different. This isn’t it.”

Rei: “If you wish for others to exist, once again, [pg129] the walls of your heart will pull you away from everyone else. A new terror of others will begin.”

Shinji: “That’s fine.”

Caption left top: • Figure 1a.32 • Shinji and Rei merging, from The End of Evangelion • 199729ya • Anime film

Shinji removes his hand from Rei’s torso and shakes her hand. Shinji chooses a world in which a barrier separates him from others. He notices the others again. Those who have already fused begin to reappear in individual silhouettes as each person regains his individuality. On the beach, Shinji is strangling Asuka. Asuka caresses his cheek with her injured right hand. As he releases his grip, Shinji weeps and a tear lands on Asuka’s cheek. Asuka blurts out, “That’s disgusting.” “The End” appears in a corner of the frame, and abruptly, the film is over.

Shinji longs for the self that has split away from him to acknowledge his remaining self. He would like for his neighbors to acknowledge him as well. And so he rejects total fusion with Rei; but he’s wary of the pain that accompanies interaction with others. Should he let himself become the object of another’s love? Alone with Asuka, the only person left who may understand him, Shinji tries to kill her. But as he strangles her, Asuka extends her hand to him. She strokes his cheek. Skin touches skin. Primitive communication, ambitions derailed. Even though he attempts to kill her, Shinji wants Asuka to understand his real intention: that what he really seeks is simply himself. But he also knows that this is impossible. Seeing this pathetic side of [pg131] Shinji, Asuka mirrors the response of society. She asserts that she finds Shinji, who is only capable of self-involved communication, “disgusting”.

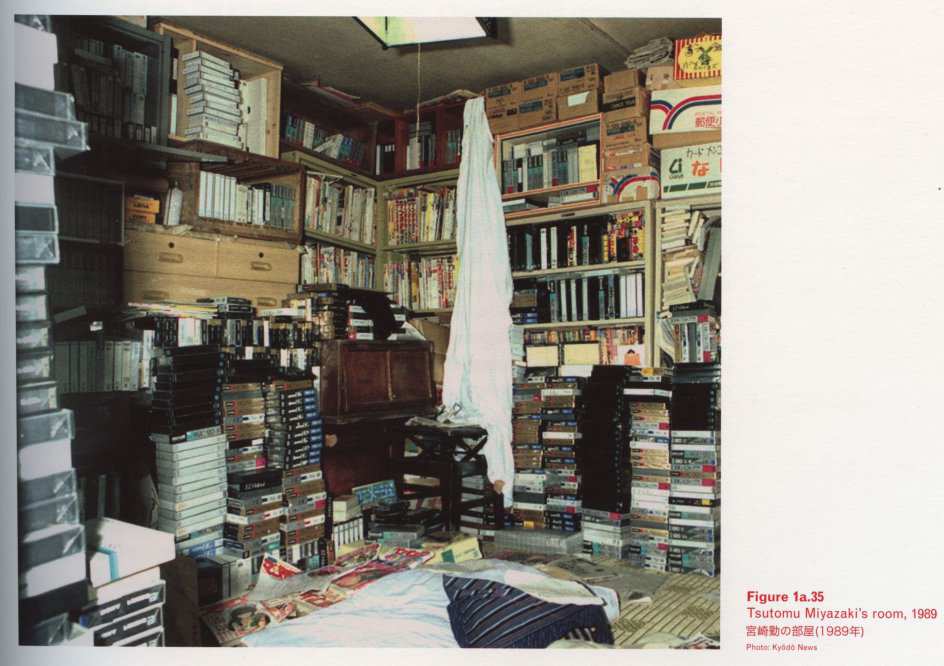

Caption bottom right: • Figure 1a.35 • Tsutomu Miyazaki’s room, 1989

In the last scene of Katayama’s novel Crying Out Love from the Center of the World, the protagonist, Saku, has grown up. With a new lover in tow, he returns to a highschool campus drenched in memories of his dead lover. He is not in the least concerned that his new lover neither knows he lost Aki to leukemia nor appreciates his memories of the dead girl. In fact, his driving purpose is to reaffirm an enduring sentimentality that he has reserved entirely for himself, and it is this that triggers sympathy in the reader.

In Evangelion, Shinji would fulfill his desire to complete a solitary journey of the heart by murdering Asuka, his only counterpart.

The drama of this murder attempt exists on the level of a child who discovers the meaning of life by killing a frog. Such paralysis signifies both the otaku’s apex and his genesis.

In a sense, the search for a place in the world, which so torments Anno’s alter-ego Shinji, is the insurmountable [pg132] challenge facing Japan. Our relief at finally putting the trauma of the war behind us was brief, for we immediately were confronted by our inability to devise an independent future. Japan is now enmeshed in the search for what it means to have a self.

On the other hand, in his “journey to self-abandonment”, Miura Jun, the man who coined the term yuru chara, asks whether or not there is a self worth searching for; the more such paradoxes emerge, the more a meaningless “journey of self-discovery”, which offers no apparent or ultimate independence, becomes the theme of Japan.

Otaku

It is impossible to avoid otaku in any discussion of contemporary Japanese culture. Although some otaku prize themselves as “genetic” otaku, all are ultimately defined by their relentless references to a humiliated self. Though obsessed with personal taste and individualism, otaku can cultivate friendships based on shared interests. They excel at radicalizing insular information. They thoroughly reject those who stray outside the boundaries of shared interests.

Japanese society has consistently ridiculed otaku as a negative element, driving such personalities into the far corners of the social fabric.

There is a slight but absolute gulf between “subculture” [zoku?] and otaku. If we define subculture as “cool culture from abroad”, otaku is “uncool indigenous Japanese culture”; as otaku insist, “at least it’s home-grown”. Otaku are mercurial, and embrace the internal contradiction of considering such definitions “un-otaku”.

Nevertheless, the incident that spurred the impulse to purge otaku from the world exposes the stark reality of otaku anthropology for all to see. After the arrest of Tsutomu Miyazaki, a kidnapper and murderer of children, media images revealed his otaku-esque existence in a windowless room lined with wall-to-wall stacks of videos5; the otaku lifestyle was thus demonized as a symbol of evil.

The otaku aspect of the cult group Aum Shinrikyo triggered a media bonanza, disseminating an impression of otaku as evil incarnate. From the amateurish technology of its self-produced propaganda videos and electric-equipped helmets for followers, to the launch of its Mahāpōsha store selling cheap homemade computers in Akihabara (Tokyo’s electronics district) [pg133] to raise cult funds, Aum Shinrikyo could be characterized by its wide-ranging otaku-esque behavior. The clincher was the sect’s creation of a detoxification system dubbed “Cosmo Cleaner”, a direct appropriation of the identically named radiation-disposal device prominently featured in Space Battleship Yamato. Aum Shinrikyo’s otaku dimension had become so extreme that the group was perceived throughout Japan both as a laughingstock and as an incomprehensible species.

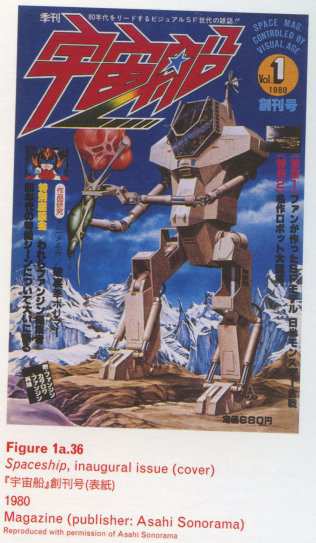

Caption right top: • Figure 1a.36 • Spaceship, inaugural issue (cover) • 198046ya • Magazine (publisher: Asahi Sonorama)

Yet otaku continue to proliferate, heedless of the criticism centered in society’s reservations about such incidents, probably because otaku existence fits so effortlessly into Japanese lifestyles.

Otaku emerged in the late 1970s. Their forerunners were obsessed with accumulating information, and radicalized the critical assessment of TV animation, science fiction, and other subcultures then perceived as nothing more than children’s entertainment. They comprised the growing fan base for Space Battleship Yamato; the intensely cliquish founding members of the special-effects science-fiction magazine Uchūsen (Spaceship), created in 198046ya by Asahi Sonorama; and the DAICON group. The definitive otaku animation works, Space Battleship Yamato and Mobile Suit Gundam, are pivotal in the way that Marcel Duchamp’s urinal is pivotal as a twentieth-century work of art; subsequent works are derived from interpretations and reinterpretations of these paradigms. Products aimed at this obsessive fan base still proliferate, and the otaku market continues to expand gradually, though it has already reached its peak.

The latest generation of otaku emerging in the post-Tsutomu Miyazaki era no longer exists in hermetic isolation. They have also ceased to attract social disdain. This is because otaku have proliferated so widely that they no longer form a minority. They are integrated so thoroughly into the mainstream that first-generation otaku have become difficult to distinguish from everyone else.

Otaku will never be outmoded and will continue to proliferate because they constantly transform themselves.

In every domain—from the world of games, to the Internet, to a world of pop-idols—otaku swiftly discover the loci of exchange between intense Eros and consciousness, never tiring in their efforts to fuse with such realms. Every otaku category sublimates into [pg134] fantasy, fueled by gargantuan information stores, integrated research, and the otaku quest for Eros. As a result, although their world has begun to overlap with reality and otaku have gradually begun to merge with the mainstream, they remain unable to shed the air of the grotesque.

Caption bottom left: • Figure 1a.37 • Store model for Seven-Eleven Japan

Seven-Eleven

Just one more, one more call from you and we can

start over

But if we keep this up, my memories of you will be

destroyed

I’ll do my best

I want to grow the teeny-tiny guts of a defeated athleteThese days, I play ’til around 8 or 9 p.m.

I go to the convenience store, I go to the disco and watch

rental videos with girls I don’t know

I don’t know if this is as good as it gets,

but none of it

compares to youIn those days, I got drunk on Kahlua-milk

These days I can drink bourbon-sodas with the guys,

but I don’t really like themLet’s get off the phone and meet in Roppongi,

come meet me, now

I want to make up with you, one more time,

over Kahlua-milkGirls are so fragile, which is why they need to be

protected, as much as possible

But I’ve never been able to be that kind of man, I’m sorry

I’ll do my best

I want to grow the teeny-tiny guts of a defeated athleteWe’re both stuck in our stupid little pride

You treated me to Kahlua-milk on my birthday

When I had one the other day, it made me want to cryLet’s get off the phone and meet in Roppongi,

come meet me, now

I want to make up with you, one more time, over

Kahlua-milk(Yasuyuki Okamura, “Kahlua-Milk”, 199036ya; lyrics and music by Yasuyuki Okamura)

![[pg135] Caption right top: <span class=separator-inline>•</span> Figure 1a.38 <span class=separator-inline>•</span> Bank Band <span class=separator-inline>•</span> Soshi soai (Like-minded musicians get together and jam; limited edition) <span class=separator-inline>•</span> 200422ya <span class=separator-inline>•</span> CD (cover) <span class=separator-inline>•</span> The CD Soshi soai consists of Bank Band’s cover versions of songs by various artists, including “Kahlua-Milk” and “Ode to Joy” (quoted in the text). Bank Band was formed by Takeshi Kobayashi and Kazutoshi Sakurai to aid their non-profit organization, “ap bank”, which makes loans to environmental projects. They seek meaning in history by archiving, respecting, and renewing it. Their goal is to travel along the vertical temporal axis of Japanese culture without reference to external factors.](/doc/anime/eva/little-boy/earthwindow-38.jpg)

[pg135] Caption right top: • Figure 1a.38 • Bank Band • Soshi soai (Like-minded musicians get together and jam; limited edition) • 200422ya • CD (cover) • The CD Soshi soai consists of Bank Band’s cover versions of songs by various artists, including “Kahlua-Milk” and “Ode to Joy” (quoted in the text). Bank Band was formed by Takeshi Kobayashi and Kazutoshi Sakurai to aid their non-profit organization, “ap bank”, which makes loans to environmental projects. They seek meaning in history by archiving, respecting, and renewing it. Their goal is to travel along the vertical temporal axis of Japanese culture without reference to external factors.

At the height of the bubble economy, from the mid-1980s to the early 1990s, Japan spent money. This economic frenzy, similar to the climate surrounding the rise of Pop Art in America, visited a Japanese culture grown obese from cultivation in a greenhouse. The vicissitudes of reality grew more compelling than fiction. With a manic feeling of having conquered the future, without any heed for the future, and trusting only the upward momentum of the bubble economy, we observed a mirage that bore us straight into the future. And when that mirage vanished, we felt relief, as if to say, “That’s right, this is what reality looks like.”

We realized that life was perfectly fine with just a modicum of joy. No need to party-hearty every day of your life. No one was starving, no one was that bored. If you were hungry, you’d go to Don Quijote. And soon, the basis of everyday life depended on convenience stores and discount shops. The local convenience store is now a significant factor in apartment-hunting.

Seven-Eleven currently dominates the convenience-store market. The chain opened its first store in 197452ya as a Japanese incarnation of American Southland Corporation’s 7-Eleven. Employing distinctly Japanese distribution strategies—including completely computerized inventory controls, meticulous replenishment of perishable goods via nine deliveries per day, and the elimination of warehouses—Seven-Eleven currently controls 10,303 of Japan’s 37,691 convenience stores, boasting the highest gross sales in the country, an annual total of more than 23 billion yen (nearly 222 million dollars).

The next revolutionary retail outlet to settle into the urban landscape was Don Quijote. It offers a unique “condensed array” retail space that suggests you’ve wandered into an Asian bazaar. Brand-name goods, [pg136] electronics, and apparel are displayed in an environment reminiscent of a tropical jungle, which customers can “explore” as they shop. It is the thrill of wandering into a maze. Don Quijote’s forty thousand products vary constantly, and it is the only place in the world where Louis Vuitton bags can be seen next to toilet paper.

Caption left top: • Figure 1a.39 • Miura Jun • Miura Jun’s Yuru Chara Show • 200422ya • DVD (cover)

The stores are open day and night, but the quintessential Don Quijote experience unfolds late at night: peak sales hours fall between 10 p.m. and midnight. Unlike the late-night markets of convenience stores, where customers make purchases to satisfy immediate needs, young people flock to Don Quijote nightly in order to “kill time” in a new kind of urban amusement, like moths to a flashlight.

The capitalist economy has become the world’s philosophy. It proliferates because it offers the image of a society where life is easy and no one starves. Pleasure motivates everything. People create environments spurred by their own desires. In Japan today, we’ve nearly perfected a living environment based on consumer supremacy that’s very comfortable, easy, and nearly stress-free.

If you have a convenience store, you’ll be fine. For a little entertainment, check out Don Quijote. Your scenario for a happy society free of starvation is now complete.

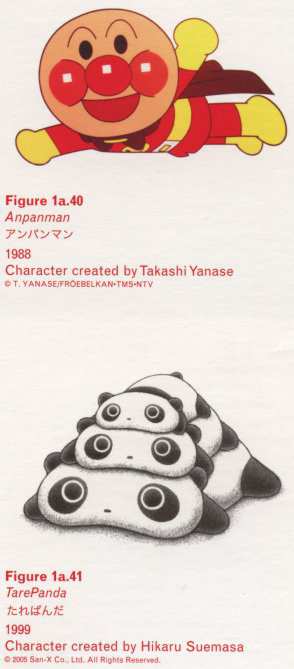

Yuru Chara

Japan is a treasure trove of kawaii characters: Hello Kitty, Pokemon, Doraemon, TarePanda (“Drooping Panda”), and Anpanman (“Bean-Paste Bread Man”)—the list goes on and on. By now, kawaii has even entered the global vocabulary.

These characters, which first won popularity with children, either were spun off from manga and anime or were corporate icons; all were regarded as promotional products. At this point, countless character are generate exclusively for merchandizing, supported by a flood of specialty magazines featuring such products. Kawaii characters, upheld by a global market, are now in riotous proliferation.

Today, with the character boom at its height, one branch of these creatures has already fallen by the wayside. Miura Jun, the multitalented popular illustrator and creator of up-to-the-minute slang—a veritable subculture king with links to the otaku world—has delved into this hopeless, stranded population, infusing [pg137] it with newfound significance and reinventing its members as yuru chara (pl. 32).