Subscripts For Citations

A typographic proposal: replace cumbersome inline citation formats like ‘Foo et al. (2010)’ with subscripted dates/sources like ‘et al2020’. Intuitive, easily implemented, consistent, compact, and can be used for evidentials in general.

I propose reviving an old General Semantics notation: borrow from scientific writing and use subscripts like ‘Gwern2020’ for denoting sources (like citation, timing, or medium).

Using subscript indices is flexible, compact, universally technically supported, and intuitive. This convention can go beyond formal academic citation and be extended further to ‘evidentials’ in general, indicating the source & date of statements.

While (currently) unusual, subscripting might be a useful trick for clearer writing, compared to omitting such information or using standard cumbersome circumlocutions.

I don’t believe the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis so beloved of 20th century thinkers & SF, or that we can make ourselves much more rational by One Weird Linguistic Trick. There is no far transfer, and the benefits of improved vocabulary/notation are inherently domain-specific. You think the same thoughts in English as you do in Chinese. But, like good typography, good linguistic conventions may be worth all told, say, even as much as 5% of whatever one values—and that’s not nothing. In ‘rectifying names’, be realistic: aim low. (It’s definitely worthwhile to do things like spellcheck your writings, after all, even though no amount of spellcheck can rescue a bad idea.)

Good Writing Conventions

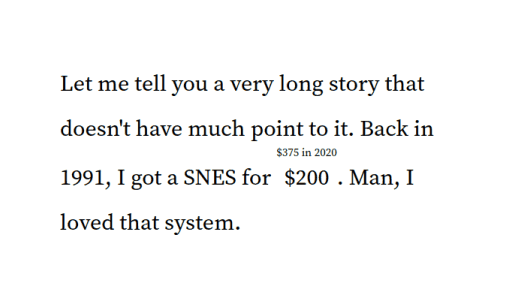

Checklist approach. I already use a few unusual conventions, like attempting to use the Kesselman Estimative words to be more systematic about the strength of my claims or always linking fulltext in citations (and improving using link annotations which do not just link fulltext but present the abstract/excerpts/summary as well), and I employ a few more domain-specific tricks like avoiding use of the word ‘significance’ in statistics contexts, automatically inflation-adjusting currencies (to avoid the trivial inconvenience of doing it by hand & so not doing it at all), or using research-specific checklists. Without straying into conlang territory or attempting to do everything in formal logic or serious eccentricity, what else could be done?

Subscripts For Metadata

One idea for more precise English writing which I think could be usefully revived is broader use of subscripts. We could encode many kinds of useful metadata: citations, dates, sources, and evidentials are ones we could use in scholarly contexts.

Distinguishing things named the same. The subscripting idea is derived from General Semantics (GS)1, which itself borrows it from standard science or math typography, like physics/statistics/mathematics/chemistry/programming: a superscript/subscript is an index distinguishing multiple versions of something, such as quantity, location, or time, eg. xt vs xt+1. They’re typically not seen outside STEM contexts, aside from a few obscure uses like ruby/furigana glosses.

Citations

However, there are many places we could use subscripting to be clearer & more compact about which version we are referring to, using them as evidentials. And because it’s clearer & more compact, we can afford to use it more places without it wasting space/effort/patience. Citations are a good use case. Why write “Friedenbach (2012)” if we can write “Friedenbach2012”? The latter is shorter, easier to read, less ambiguous (especially if we use it in parentheticals, see Friedenbach (2012)), and doesn’t come in a dozen different slightly-varying house styles. Why not use it for other things, like software versions or probabilities too?

Evidentials

But why restrict subscripting to formal publications or written documents? Apply it to any quote, statement, or opinion where indexing variables like time might be relevant. Refusing to allow easy references to anything not a book is but codex chauvinism.

One convention, arbitrary metadata. It is a unified notation: regardless of whether something was thought, spoken, or written by me in 2020, it gets the same notation—“Gwern2020”. The evidential can be expanded as necessary: if it’s a paper or essay, the ‘2020’ can be a hyperlink, or if it’s a ‘personal communication’, then there can be a bibliography entry stating as much, or if it’s the author about their own beliefs/actions/statements in 2020, further information neither necessary nor usually possible (and it avoids awkward custom phraseology like “As I thought back in 2020 or so…”). In contrast, normal citation style cumbersomely uses a different format for each, or provides no guidance: how do you gracefully cite a paper written one year but whose author changed their mind 5 years later based on new results and who told you so 10 years after that? (“Dr. Bach originally maintained A (Bach et al. (200026ya)2) but gradually modified his position until 200521ya when he recalls writing in his diary he had lost all confidence in A (personal communication, according to 2015)…”)

Generalized Evidentials

Evidentials using authors or years are short enough that they can be laid out as simple subscripts. There is no new typographic issue with that. But as discussed above, there is no need to limit it to formal publications; knowledge can be derived from many sources, and even in the most formal academic writing, there are the occasional pseudo-citations like “2010 (personal communication)”. A complete evidential—like “Foo told me so on the second day of our Black Forest camping trip in 2010”—would be awkward to read if naively subscripted.

In a noninteractive format, such evidentials probably must be relegated to footnotes/endnotes/sidenotes; in an interactive format like HTML, we can do better.

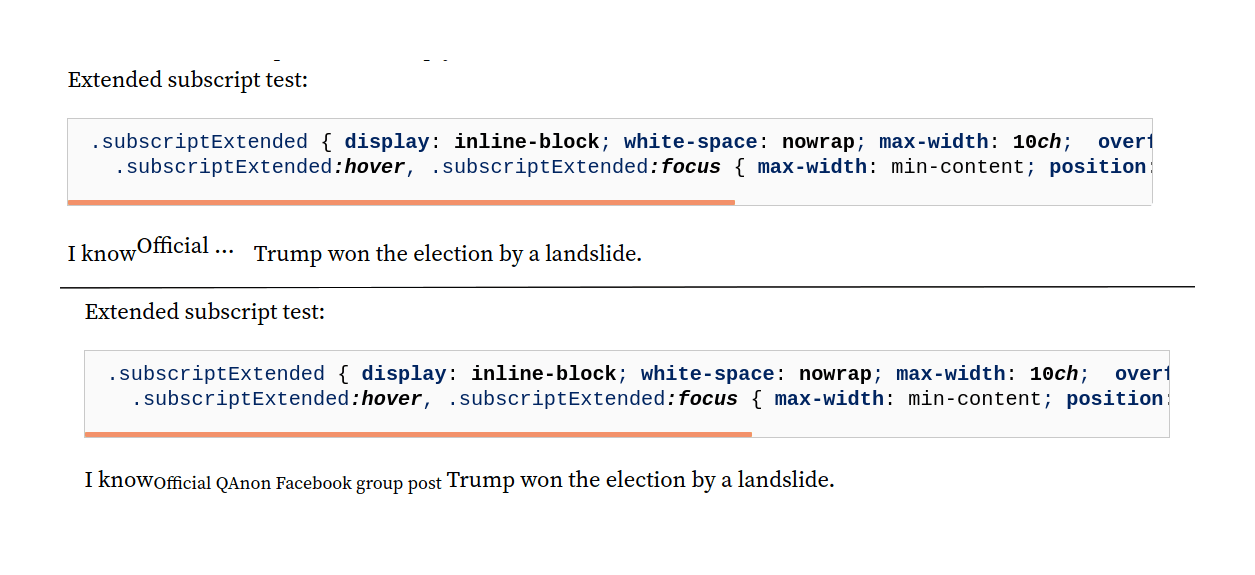

For HTML, CSS supports setting maximum widths & truncating with ellipsis overflows, while expanding width on hover, so one can do something roughly like this:

.evidential { display: inline-block; white-space: nowrap; max-width: 10ch; overflow: hidden; text-overflow: ellipsis; }

.evidential:hover, .evidential:focus { max-width: min-content; position: relative; bottom: -0.5em; font-size: 80%; }

CSS prototype of expanding subscripts for long evidentials.

Then the first 10 characters will be displayed, truncated by ‘…’, and if the reader hovers over it with their mouse, it expands to reveal the arbitrarily-long evidential. The CSS seems tricky to get right, so it might be easier to resort to JavaScript-based popups like my existing link annotations/definitions using popups.js.

Citation Evidentials

Citation contexts. One of the more complained about weaknesses of citations as untyped directional links is that they are often interpreted as an endorsement, even though references are used in innumerable ways. Parsing out the meaning of a citation is one of the biggest challenges of any citation analysis, especially for scientometrics: is a citation in a new paper there because the old work is bad and being criticized & debunked, or because it is the key prior art for the new paper, or it is a justification for a claim in the new paper (and if so, is this claim key or minor? how certain is the citer that it is correct?6), or it merely cited as a placeholder citation for a well-known fact or as a general background reference?

Subscripted evidentials allow a relatively lightweight way of encoding such properties: simply append them in the subscript for those who care.7

Chess commentary-style. For a concrete example, one could draw inspiration from chess annotation symbols, which are compact, intuitive, and writers/readers may already be a little familiar with them. In chess annotations, ‘!’ is good while ‘?’ is bad, and they can be intensified by duplication (‘!!’, ‘??’) or weakened by combination (interrobang-like ‘!?’ and ‘?!’). Then one could use them easily:

We build on et al2020!!, borrowing a trick from 2021!, on the task of optimally petting domesticated cats (1994), which fails to replicate et al2019? on the value of backwards-stroking (as well as et al2018??, recently shown to be fraudulent).

This clearly divvies up importance between the key work, less important but relevant works, tangential references, and highly critical citations—if a paper is a narrative, then evidentials let one see the dramatis personae at a glance to know who are the allies, who are the enemies, and who are bystanders.

Or one could prefer to instead highlight importance: perhaps ‘key papers’ get an asterisk to indicate they are the most important ones (using one of the many other stars to avoid confusion with footnotes). Or agreement/disagreement could be indicated, such as by ‘✓’ vs ‘❎’ (NEGATIVE SQUARED CROSS MARK).

Semi-automatable. There are many possible things one could reasonably encode, but the main problem is that there is no simple automatic way to do so (after all, this would not be necessary if there was) and authors typically do not want to do this—such explicit epistemology is exhausting! The latest scientometric efforts like Semantic Scholar use large language neural nets like GPT-4 to attempt to infer the semantics of a citation; these might make it feasible to do semi-automated edits of finished documents, where the document can be parsed, the NN can be fed all of the citations’ fulltexts, read the document text, and can suggest the correct semantic markup for each citation, which the human author validates.

Too automatable? But this then raises another issue: if such systems can already do it at sufficiently high accuracy that the human author only has to spend a minute double-checking, then is it worthwhile to encode them at all? It may be better for the author to not bother, and let the machines figure it out as necessary; then the readers can just rely on a tool, like a website or web browser or PDF reader plugin, to preprocess any paper they are reading to add the relevant semantic notations. (See for example Elicit.)

Technical Support

Subscripts: already in a theater near you. Because it’s already used so much in technical writing, subscripting is reasonably familiar to anyone who took highschool chemistry & can be quickly figured out from context for those who’ve forgotten, and it’s well-supported by fonts and markup languages and word processors: it’s written x~t~ in Pandoc Markdown & some Markdown extensions like markdown-it (but not Reddit), x<sub>t</sub> in HTML, x<subscript>t</subscript> in DocBook, x_t in TeX/LaTeX, x\ :sub: \t in reStructuredText; and it has keybindings C-= in Microsoft Office, C-B in LibreOffice, C-, in Google Docs etc. So subscripting can be used almost everywhere immediately.

Note that we do need to use existing ways of subscripting, and we can’t fake it using the Unicode super/subscript characters: they look weird, break a lot of tools (eg. you can’t reliably search for them in all browsers), and omit most of the alphabet so you couldn’t even write ‘2020b’ (it skips from ‘a’ to ‘e’, although including LATIN SUBSCRIPT SMALL LETTER SCHWA ‘ₔ’ for some reason).

Example Use

Example: here are 3 versions of a text; one stripped of citations and evidentials, one with them written out in long form, and one with subscripts:

I went to Istanbul for a trip, and saw all the friendly street cats there, just as I’d read about in Abdul Bey; he quotes the local Hakim Abdul saying that the cats even look different from cats elsewhere (but after further thought, I’m not sure I agree with that there). I and my wife had a wonderful trip, although while she clearly enjoyed the trip to the city, she claimed the traffic was terribly oppressive and ruined the trip. (Oh really?)

In 201016ya, I went to Istanbul for a trip, and saw all the friendly street cats there, just as I’d read about in Abdul Bey’s 200026ya Street Cats of Istanbul; he quotes the local Hakim Abdul in 197056ya saying that the cats even look different from cats elsewhere (but after further thought as I write this now in 2020, I’m not sure I agree with Bey (200026ya)). I and my wife had a wonderful trip, although while she clearly enjoyed the trip to the city, on Facebook she claimed the traffic was terribly oppressive and ruined the trip. (Oh really?)

I2010 went to Istanbul for a trip, and saw all the friendly street cats there, just as I’d read about in Abdul Bey2000 (Street Cats of Istanbul); he quotes the local Hakim Abdul1970 saying that the cats even look different from cats elsewhere (but after further thought, I’m not sure I2020 agree with Bey2000). I and my wife had a wonderful trip, although while she clearly enjoyed the trip to the city, she claimedFB the traffic was terribly oppressive and ruined the trip. (Oh really?)

In the first version, suppressing the metadata leads to a confusing passage. What did Bey write? We don’t learn when Abdul expressed his opinion—which is important because Istanbul, as a large fast-growing metropolis, may have changed greatly over the 40 years from quote to visit. When did the speaker become skeptical of the claim Istanbul cats both act & look different? What might explain the wife’s inconsistency, and which version should we put more weight on?

The second version answers all these questions, but at the cost of prolixity, jamming in comma phrases to specify date or source. Few people would want to either write or read such a passage, and the fussiness has a distinctly fussy pseudo-academic air. Unsurprisingly, few people will bother with this—any more than they will bother providing inflation-adjusted dollar amounts of something from a decade ago (even though that’s misleading by a good 15% or so, and compounding), or they’d want to check a paywalled paper, or redo calculations in Roman numerals.

The third version may look a little alien because of the subscripts, but it provides all the information of the second version plus a little more (by making explicit the implicit ‘2020’), in considerably less space (as we can delete the circumlocutions in favor of a single consistent subscript), and reads more pleasantly (the metadata is literally out of the way until we decide we need it).

Possible Alternative Notation

I considered 3 alternatives:

Superscripts: already overloaded as footnotes & powers

Bang notation: another possible notation for disambiguating, is the “X!Y” notation (apparently derived from UUCP bang notation), which is associated with online fandoms & fanfiction, and gives notation like “2020!gwern”.

This notation puts the metadata first, which is confusing yodaspeak (what does the ‘2020’ refer to? It dangles until you read on); it makes it inline & full-sized, and then tacks on an additional character just to take up even more space; it’s confusing and unusual to anyone who isn’t familiar with it from online fanfiction already, and to those who are familiar, it is low-status and has bad connotations.

Ruby annotations: as mentioned above, there is standardized HTML support (but with spotty browser support & no support at all in most other formats) for ‘ruby’ annotations which are similar to superscripts and intended for interlinear glosses.

Unfortunately, in a horizontal language like English (as opposed to Chinese/Japanese), they require extremely high line-heights to be at all legible. Example:

Example of HTML ‘ruby’ interlinear gloss (eg.

<ruby>$200<rt>$375 in 2020</ruby>).New symbols: no font, editor, or word processor support kills any new symbol proposal, and can be rejected out of hand.

Disadvantages

Deal-breaker: low status? The major downside, of course, is that subscripting is novel and weird. It at least is not associated with anything bad (such as fanfics), and is associated with science & technology, but I’m sure it will deter readers anyway. Does it do enough good to be worth using despite the considerable hit to weirdness points? That I don’t know.

Date Ranges

The next day the little prince came back.

“It would have been better to come back at the same hour,” said the fox. “If, for example, you come at 4 o’clock in the afternoon, then at 3 o’clock I shall begin to be happy. I shall feel happier and happier as the hour advances. At 4 o’clock, I shall already be worrying and jumping about. I shall show you how happy I am! But if you come at just any time, I shall never know at what hour my heart is to be ready to greet you… One must observe the proper rituals…”

“What is a ritual?” asked the little prince.

“Those also are actions too often neglected,” said the fox. “They are what make one day different from other days, one hour from other hours. There is a ritual, for example, among my hunters. Every Thursday they dance with the village girls. So Thursday is a wonderful day for me! I can take a walk as far as the vineyards. But if the hunters danced at just any time, every day would be like every other day, and I should never have any vacation at all.”

So the little prince tamed the fox.

Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.

Date slippage. With inflation, what was once an absolute unit slowly becomes a relative unit, with a hidden multiplier, leading to ever greater mental slippage: it is misleading by default, and one must effortfully correct, which one will often not do. A similar issue can happens with dates and durations, in both directions: a year like “1972” is absolute but it may be relevant for its distance from the present moment, which keeps changing.

Trapped in eternal present. People often note that they feel like they are simply in a “Big Now” where time infinitely scrolls, and don’t feel like time or history is actually passing, that it is the present year; their mental default is somehow still frozen in 200026ya, and they have to remind themselves that it is in fact the (much later) present year. Somehow, to many, the year 200125ya is still a sci-fi future from a Kubrick movie, and not an increasingly-distant past a generation or more ago. One might write in a 2022 blog post “what happened 50 years ago [in 197254ya]?”, which is entirely comprehensible… as long as one didn’t write it in early January 2022 when people are still adjusting to the new calendar year and wonder what happened in 197155ya, and someone reading it a decade later might be severely confused about the concern over the year 198244ya. This goes in the other direction: ‘1972’ is 50 years ago (as I write this), but does it feel an entire half-century in the past? In 2022, when the movie sequel Top Gun Maverick aired starring, of course, Tom Cruise, more than one person was startled to actually do the arithmetic for the 198640ya release date of Top Gun and realize it was ~36 years ago. Or when a live-action Scooby-Doo reboot sans Scooby-Doo was announced, I was bemused to note that the franchise was now older than almost everyone debating the omission, as it started in 196957ya or >53 years ago—which means that Top Gun & Scooby-Doo are closer in time than you to Top Gun. (Does it feel that way?) Such “time ghost” comparisons can doubtless be generated indefinitely as our intuitive grasp of timelines weakens.

Context collapse. Why are past dates getting squeezed like this? Many eras seem quite distinct: the 1920s are different from the 1930s, which are totally separate from the 1940s in my mind, and likewise the 1950s and 1960s slot into place, more or less; but come the 1970s, and everything gradually blends together. I have a good feel for technology & science over that time, and can with trouble reconstruct geopolitics, but in other areas like general culture, I feel you could fool me with sequences decades out of order. Did Paul McCartney have his greatest album hits in the 1960s, or the 1990s? I’d believe you if you told me either. Were the Monkees the 1950s, or the 1970s, and were they a band, TV show, or both, and did they end in the 1970s or 2020s during a reunion tour? It’s hard to maintain a chronology of movies or music albums when one watches them indiscriminately, pulling from a century ago as easily as tracks released today, and how can we take the passage of time too seriously if Paul McCartney is still, in 2022, performing in concerts with guests such as Bruce Springsteen, while elsewhere Bob Dylan continues releasing albums while touring & writing books?

Recycling without updating. Aside from that sort of “context collapse” in time, fashion cycles recycle the same things in minor variations, like environmentalism or political-correctness, which produces awkward repetitions: a feminist comparison to the misogyny of college education “50 years ago” is rhetorically effective in the 1990s, where it harks back to the 1940s (pre-second-wave feminism) and an America with few female graduate students or tenured professors, but it is drastically less so when uttered in 2022 and referring to 197254ya, well into the tidal wave of female entry into higher ed which saw them reach a majority of undergrads just a few years later (a milestone they would never relinquish, and has since escalated to >60% of undergrads).

To err is human. So what can be done about this? If someone is seriously committed to making a case for 197254ya being tantamount to the medieval dark ages, then fine; but perhaps they just hadn’t quite thought about the implications of quoting a spicy passage from something written in the 1990s—after all, the 1990s, that was not that long ago, was it? It still seems so present & real to me… (The trend in the 2020s of rebooting every 1990s media franchise, to appeal to aging Millennials, scarcely helps.) One can try to be mindful and calculate deltas as a routine matter of reading, similar to checking whether a number of meaningful by shifting it an order of magnitude up & down, and simply remember the decade-level differences: 2020s to 1990s is 3 decades, to 1980s is 4 decades etc. But this is something so mechanical & straightforward, and dates so pervasive, that this is a poor solution: we will still subtly slip into a vague timeless “Now”.

Denote years-since? It seems like something that a better notation could help with. Scientists, for example, do not trust to absolute dates and expect readers to juggle piles of dates millennia apart, but explicitly use durations like “100kya” or “1mya”. This is not too exotic, and I think most readers would understand what “10ya” means, particularly in a context. So, this makes a natural fit with subscript citations: as we are already putting years in subscripts, why not put in date durations like “10ya”?

Tom Cruise has returned for Top Gun Maverick (2022), the sequel to Top Gun (198636ya).

Regexp-able. This is compact, intuitive, and can be automated—particularly if one uses decimal separators for numbers but not years, so most dates can be matched as 4-digit whole numbers starting 1–2 and surrounded by non-digits (something like [^0-9][12][0-9][0-9][0-9][^0-9]).

Hide duplicates & in cites. For particularly date-heavy writings where the same dates come up repeatedly, this might result in too much subscripting: unlike citations, which must be displayed at each claim to serve their role, date-range subscripting is a convenience, a reminder of date distances, so after the first instance of a date, the rest can be suppressed. (This is also true of inflation-adjusting currency, but amounts tend to be fairly unique so it is less of a problem.) It would not apply to subscripted citations themselves, as combinations like ‘Foo20202ya’ or ‘Foo2020 (2ya)’ are probably unworkable, and in any case, with citations, the year itself tends not to be too important given the realities of academic publishing, where papers can take decades to be formally published, or the work can take more decades to be applied or built on: if the year is important, it can be discussed normally. (“And then in 20202ya, Foo2020 revolutionized the field by reticulating the splines with unprecedented efficiency…”)

And for date ranges, particularly EN DASH-separated date ranges of years, one could subscript the EN DASH itself with the duration of the beginning/ending, in addition to the duration from the ending to the present. Since the duration of the date range itself will usually be small, providing the first one is not so necessary and can be suppressed. Which might look a little like this:

Negotiations for the ¥ revaluation lasted 1987–7199430ya.

External Links

Discussion: LW

Appendix

Inflation

My general approach of automatically inflation-adjusting dollar/₿ amounts to the current nominal (ie. real) amount, rather than default to presenting ever-more-misleading nominal historical amounts, could be applied to many other financial assets.

As far as almost all financial software is concerned, ‘a dollar is a dollar’, and as long as credits & debits sum to zero, everything is fine; inflation is, somewhat bizarrely, almost completely ignored, and left to readers or analysts to haphazardly handle it as they may (or may not, as is usually the case).

Here are 4 ideas of ‘inflation adjustments’ to make commonly-cited economic numbers more meaningful to our decision-making:

rewrite individual stock returns to be always against a standard stock index, rather than against themselves in nominal terms

annotate stock prices on a specific date with their #1 statistic from that date to ‘today’

rewrite currencies to year-currencies, with ‘real’ currency amounts simply being reported in the most recent year-currency

rewrite year-currencies into the NPV of the next-best alternative investment, which represents the compounding opportunity cost

Benchmarking

Index

Stock prices would benefit from being reported in meaningful terms like net real return compared to an index like the S&P 500 (reinvesting), as opposed to being reported in purely nominal terms: how often do we really care about the absolute return or %, compared to the return over alternatives like the default baseline of simple stock indexing?

Typically, the question is not ‘what is the return from investing in stock X 10 years ago?’ but ‘what is its return compared to simply leaving my money in my standard stock index?’.

If X returns 70% but the S&P 500 returned 200%, then including any numbers like ‘70%’ is actively misleading to the reader: it should actually be ‘−130%’ or something, to incorporate the enormous opportunity cost of making such a lousy investment like X. (See the performance-pay Nobel for an example of why CEO pay should be adjusted by how much their companies beat their competitors instead of simply the stock price increasing over time.)

The original nominal return would fit nicely in a subscript appended to the more important benchmark-adjusted return:

I made −80%20 by investing in X 5 years ago! Subscribe to my newsletter for more investing tips.

A logical extension of index benchmarking is to include some form of risk-adjustment (a Sharpe ratio?), to avoid cherrypicking or making lucky investments look the best, perhaps by taking into account a stock’s beta. Unfortunately, estimating true beta is difficult, and beta is constantly changing, and so there are many ways to calculate betas; it is not clear to me which one is best, nor that presenting a beta-adjusted benchmark would be intuitive or aid understanding. So risk-adjustment might be an adjustment too far.

Event

Another example of the silliness of not thinking about the use of numbers: ever notice those stock tickers in financial websites like WSJ articles, where every mention of a company is followed by today’s stock return (“Amazon (AMZN: 2.5%) announced Prime Day would be in July”)? They’re largely clutter: what does a stock being up 2.5% on the day I happen to read an article tell me, exactly?

But what could we make them mean? In news articles, we have two categories of questions in mind:

how it started (how did the efficient markets react)?

When people look at stock price movements to interpret whether news is better or worse than expected, they are implicitly appealing to the EMH: “the market understands what this means, and the stock going up or down tells us what it thinks”.

So all ‘tickercruft’ is a half-assed implicit event study (which is only an event if you happen to read it within a few hours of publication—if even that). “GoodRx fell −25% when Amazon announced its online pharmacy. Wow, that’s serious!”

To improve the event study, we make this rigorous: the ticker is meaningful only if it captures the event. Each use must be time-bracketed: what exact time did the news break & how did the stock move in the next ~hour (or possibly day)? Then that movement is cached and displayed henceforth.

It may not be perfect but it’s a lot better than displaying stock movements from arbitrarily far in the future when the reader happens to be reading it.

How it’s going (since then)?

When we read news, to generalize event studies, we are interested in the long-term outcome. (“It’s a bold strategy, Cotton. Let’s see how it works out for them.”) So, similar to considering the net return for investment purposes, we can show the (net real index adjusted) return since publication.

The net is a high-variance but unbiased estimator of every news article, and useful to know as foreshadowing: imagine reading an old article with the sentence “VISA (V: +0.01% today) welcomes its new president for 2020.”, or “VISA welcomes its exciting new CEO John Johnson, who will take over starting in 2020 (V: −30%80%)”?

The latter is useful context. V being up 0.01% the day you happen to read the article many years later, however, is not useful context for… anything.

Document tooling-wise, this is easy to support in Markdown. They can be marked up the same way as my inflation-adjustment variables (eg. [$10]($2020)), like [V](!N "2019-04-27"). For easier writing, since stock tickers tend to be unique (there are not many places other than stock names that strings like “V” or “AMZN” would appear, as 4-letter acronyms are mostly unused), the writer’s text editor can run a few thousand regexp query-search-and-replaces (there are only so many stocks) to transform V → [V](!N "2019-04-27") to inject the current day automatically.8

Year-Currencies

It would also be useful to make temporal adjustments in regular accounting software, to treat each year of a currency as a foreign currency, with inflation defining the temporal exchange rate.

One would have year-currencies like ‘2019 dollars’ vs ‘2020 dollars’ and so on, and compute with respect to a particular target-year like ‘2024 dollars’. This allows for much more sensible inter-temporal comparisons of expenditures or income, which do not simply reflect (usually unrelated) inflation rate changes and weird expenditure-currency-time-weighted nominal sums, and which would make clearer things like when real income is declining due to lack of raises.

Accounting software like ledger/hledger already mostly support such things through their foreign currencies, but they don’t make it necessarily easy to write. Some syntactic sugar would help. Like $ is always a shortcut to USD, regardless of whether that is a dollar in 1792234ya or 2024; but it could be redefined as simply referring to the USD in the year of that transaction and be equivalent to a year-currency like 2024$. Then no additional effort by the user is necessary, because all transactions already have to have dates.

NPV-Investment Units

We could go further: one should not hold much currency, because in addition to inflation nibbling away at its value, it is a bad investment. If you hold a dollar permanently, you are foregoing a better alternative investment (like a stock index, eg. VTSAX), so you suffer from both inflation and severe opportunity cost. Often, the opportunity cost is a lot larger, too.

If we don’t try to express everything as atemporal dollars, or even a year-currency, what units should we use?

Accounting exists reflect the reality of our decisions & financial health: this is the ultimate goal of accounting which goes beyond just a crude list of account credits/debits or list of assets, which inevitably requires building a simple ‘model’, with judgments about risks and depreciation and opportunity cost (which is why ‘cash flow is a fact, all else is opinion’).

This is also why accounting systems are never feature-complete, and always keep sprouting new ad hoc features & flags & reports, eventually embodying Greenspun’s tenth rule with their own, often ad hoc and extremely low-quality, built-in programming language. Accounting is not a simple problem of just tracking some movements of a few kinds of assets like ‘dollars’ or ‘cash’ in and out of some ‘accounts’. Accounting is as complex as the world, because we always want more informative models of our financial position, and have more domain-specific knowledge to encode, and people will always differ about what they think the causal models are or what the future will be like, and this will cause conflicts over ‘accounting’. Accounting, like statistics, is ultimately for decision-making: a failure to make this explicit will lead to many confusions & illusions in understanding the purpose of accounting or things like ‘GAAP’. Accounting systems should never delude themselves about this intrinsic complexity by pretending it doesn’t exist and trying to foist it onto the users, but accept that they have to handle it and provide real solutions, like being built with a properly supported language like a Lisp or Python, instead of fighting a rearguard action by adding on features ad hoc as users can ram them through to meet their specific needs.

Simply listing everything in dollar amounts fails to do this. When we compare individual stocks to the S&P 500, why stop there? Why not denominate everything in S&P 500 shares? This would better reflect our actual choice (“spend on X” vs “save in VTSAX”).

Like the year-currencies, this is fine as far as it goes, but it suffers from its own version of the ‘nominal’ vs ‘real’ illusion, by omitting a kind of intrinsic ‘deflation’ from the opportunity cost of compounding: if we simply do it the default way by defining a daily VTSAX exchange rate and inputting everything in year-currencies, which get converted to final VTSAX numbers for reports, we do take into account the increase in value of a VTSAX share over time, but we do not take into account something fairly important—the income from the index. This would systematically bias reports by when a share was purchased: older shares are more valuable, assuming we buy-and-hold, and especially if we reinvest that. (VTSAX pays out relatively little as dividends, so the problem isn’t so big, but for other alternatives, like bonds, this omission might be wildly misleading.)

We presumably do track income from all investments properly, and so indirectly the opportunity cost is reflected in the balance sheets; the issue is not that it leads to wrong final numbers, but that it obscures the financial reality. That of course is true of everything in accounting (sooner or later it all shows up in the assets or cash flow—fail to track depreciation properly and eventually there will be a large expensive expense for replacement/repair; fail to buy insurance or self-insure, and an expensive risk will happen etc.), and the point of accounting is to show such things beforehand, and let us see the costs & benefits now.

So the daily VTSAX share price (“mark-to-market”) should instead be treated as “held-to-maturity” (ie. we plan to do something like “hold it until the year 202X, after which we will sell it during retirement”), and the daily mark reflects the predicted NPV of holding VTSAX for Y years while reinvesting & compounding. The further back in time the VTSAX share, the more the ‘exchange rate’ reflects the future income & compounding (because we require several 2024 VTSAX shares to equal the value of 1 VTSAX share we bought-and-held in 200026ya, because that share turned into several 2024 VTSAX shares all on its own).

Then we get correct real opportunity-costs of expenses over time: our decision to spend $10 on Beanie Babies in 2000 correctly reflects the real long-term cost to us of not putting that money into an index, and we can compute out the actual (or predicted) cost at any given date, and better see whether that asset performed well or the expense was justified. (Did investing in those Beanie Babies beat the alternative, or did our asset total gradually wither each year VTSAX outperformed and in retrospect the decision got worse and we refused to realize the loss? Did that $10 of ice cream as a teen make us happier than $100 in retirement we can’t spend on anything we care about?)

This requires a bit more implementation effort, but still is not too hard: the target date can be specified by the user upfront once, and a simple, fair extrapolation of future income/returns used (eg. a simple average of all historical ones). If the user has so much that they can’t save tax-free, a fudge factor can be added for taxes (updated after each actual tax filing if the user desires the greater accuracy). As the daily VTSAX share prices are updated however they are normally, the NPV estimate is updated by the ledger software without any further work from the user. And $ doesn’t need to be further modified, it simply remains a year-currency like the previous idea.

So for the user, this should be scarcely any more difficult than normal accounting software usage: one inputs transactions every day in a normal dollar amount, the stock price is updated by a script or API, and the main user-visible change is defaulting to VTSAX_202X units instead of 2024$ units, unless the user asks for 2024$ reports etc.

This provides a final, true, real accounting of all assets & expenses in a way which makes intertemporal comparison decision-relevant by default, while preserving all metadata necessary for standard financial reports or accounting.