The Existential Risk of Math Errors

Mathematical mistake/error-rates limit our understanding of rare risks and ability to defend against them.

How close does formal mathematical proof empirically come to perfection? Any error rate >0 puts lower bounds on our ability to become extremely confident in claims about extremely rare events, such as some existential risks.

Most discussion of the topic turns out to be entirely anecdotal (as is this one), but indicate that serious errors are, like in most human endeavours, common: it is not unusual for a widely-accepted proof to have gaps or severe flaws or even be unreparable, and for the claim to turn out to be false. Curiously, it seems much more common for proofs to be flawed but the claim still true than the claim false.

This suggests that the error rate of incorrect proofs is not such a concern after all; and it supports ‘psychological’/‘social’ meta-mathematical views, which hold that proofs are less about formal rigor, and more about guiding other mathematicians through a mental process which will convince them of the truth of a claim and provide some kind of insight, and are not themselves the important thing nor how claims are ‘actually proven’.

How empirically certain can we be in any use of mathematical reasoning to make empirical claims? In contrast to errors in many other forms of knowledge such as medicine or psychology, which have enormous literatures classifying and quantifying error rates, rich methods of meta-analysis and pooling expert belief, and much one can say about the probability of any result being true, mathematical error has been rarely examined except as a possibility and a motivating reason for research into formal methods. There is little known beyond anecdotes about how often published proofs are wrong, in what ways they are wrong, the impact of such errors, how errors vary by subfield, what methods decrease (or increase) errors, and so on. Yet, mathematics is surely not immune to error, and for all the richness of the subject, mathematicians can usually agree at least informally on what has turned out to be right or wrong1, or good by other criteria like fruitfulness or beauty. 2004 claims that errors are common but any such analysis would be unedifying:

An agent might even have beliefs that logically contradict each other. Mersenne believed that 267-1 is a prime number, which was proved false in 1903123ya, cf. 1951. [The factorization, discovered by Cole, is: 193,707,721 × 761,838,257,287.]…Now, there is no shortage of deductive errors and of false mathematical beliefs. Mersenne’s is one of the most known in a rich history of mathematical errors, involving very prominent figures (cf. De et al 1979, 269–270). The explosion in the number of mathematical publications and research reports has been accompanied by a similar explosion in erroneous claims; on the whole, errors are noted by small groups of experts in the area, and many go unheeded. There is nothing philosophically interesting that can be said about such failures.2

I disagree. Quantitative approaches cannot capture everything, but why should we believe mathematics is, unlike so many other fields like medicine, uniquely unquantifiable and ineffably inscrutable? As a non-mathematician looking at mathematics largely as a black box, I think such errors are quite interesting, for several reasons: given the extensive role of mathematics throughout the sciences, errors have serious potential impact; but in collecting all the anecdotes I have found, the impact seems skewed towards errors in quasi-formal proofs but not the actual results. One might say that reviewing math errors, the stylized summary is “although the proofs are usually wrong, the results are usually right.”

I find this highly surprising and nontrivial, and in striking contrast to other fields I am familiar with, like sociology or psychology, where usually wrong methods lead to wrong results—it is not the case in the Replication Crisis that flaws like p-hacking are merely ‘framing a guilty man’, because followup with more rigorous methods typically shows effects far smaller than measured or predicted, or outright reversal of direction. This difference may tell us something about what it is that mathematicians do subconsciously when they “do math”, or why conjecture resolution times are exponentially-distributed, or what the role of formal methods ought to be, or what we should think about practically important but unresolved problems like P=NP.

Untrustworthy Proofs

Beware of bugs in the above code; I have only proved it correct, not tried it.

When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains is often more improbable than your having made a mistake in one of your impossibility proofs.

In some respects, there is nothing to be said; in other respects, there is much to be said. “Probing the Improbable: Methodological Challenges for Risks with Low Probabilities and High Stakes” discusses a basic issue with existential threats: any useful discussion will be rigorous, hopefully with physics and math proofs; but proofs themselves are empirically unreliable. Given that mathematical proofs have long been claimed to be the most reliable form of epistemology humans know and the only way to guarantee truth3, this sets a basic upper bound on how much confidence we can put on any belief, and given the lurking existence of systematic biases, it may even be possible for there to be too much evidence for a claim ( et al 2016). There are other rare risks, from mental diseases4 to hardware errors5 to how to deal with contradictions6, but we’ll look at mathematical error.

Error Distribution

When I asked what it was, he said, ‘It is the probability that the test bomb will ignite the whole atmosphere.’ I decided I would check it myself! The next day when he came for the answers I remarked to him, ‘The arithmetic was apparently correct but I do not know about the formulas for the capture cross sections for oxygen and nitrogen—after all, there could be no experiments at the needed energy levels.’ He replied, like a physicist talking to a mathematician, that he wanted me to check the arithmetic not the physics, and left. I said to myself, ‘What have you done, Hamming, you are involved in risking all of life that is known in the Universe, and you do not know much of an essential part?’ I was pacing up and down the corridor when a friend asked me what was bothering me. I told him. His reply was, ‘Never mind, Hamming, no one will ever blame you.’

…of the two major thermonuclear calculations made that summer at Berkeley, they got one right and one wrong.

Toby Ord, The Precipice 2020

This upper bound on our certainty may force us to disregard certain rare risks because the effect of error on our estimates of existential risks is asymmetric: an error will usually reduce the risk, not increase it. The errors are not distributed in any kind of symmetrical around a mean: an existential risk is, by definition, bumping up against the upper bound on possible damage. If we were trying to estimate, say, average human height, and errors were distributed like a bell curve, then we could ignore them. But if we are calculating the risk of a super-asteroid impact which will kill all of humanity, an error which means the super-asteroid will actually kill humanity twice over is irrelevant because it’s the same thing (we can’t die twice); however, the mirror error—the super-asteroid actually killing half of humanity—matters a great deal!

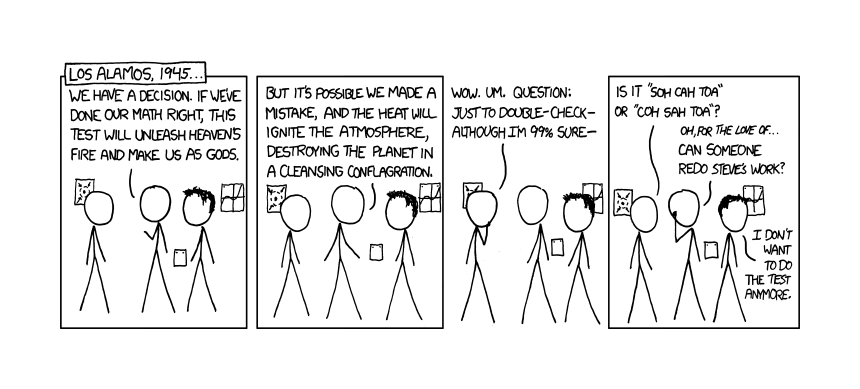

XKCD #809 “Los Alamos”

How big is this upper bound? Mathematicians have often made errors in proofs. But it’s rarer for ideas to be accepted for a long time and then rejected. But we can divide errors into 2 basic cases corresponding to type I and type II errors:

Mistakes where the theorem is still true, but the proof was incorrect (type I)

Mistakes where the theorem was false, and the proof was also necessarily incorrect (type II)

Before someone comes up with a final answer, a mathematician may have many levels of intuition in formulating & working on the problem, but we’ll consider the final end-product where the mathematician feels satisfied that he has solved it. Case 1 is perhaps the most common case, with innumerable examples; this is sometimes due to mistakes in the proof that anyone would accept is a mistake, but many of these cases are due to changing standards of proof. For example, when David Hilbert discovered errors in Euclid’s proofs which no one noticed before, the theorems were still true, and the gaps more due to Hilbert being a modern mathematician thinking in terms of formal systems (which of course Euclid did not think in). (David Hilbert himself turns out to be a useful example of the other kind of error: his famous list of 23 problems was accompanied by definite opinions on the outcome of each problem and sometimes timings, several of which were wrong or questionable7.) Similarly, early calculus used ‘infinitesimals’ which were sometimes treated as being 0 and sometimes treated as an indefinitely small non-zero number; this was incoherent and strictly speaking, practically all of the calculus results were wrong because they relied on an incoherent concept—but of course the results were some of the greatest mathematical work ever conducted8 and when later mathematicians put calculus on a more rigorous footing, they immediately re-derived those results (sometimes with important qualifications), and doubtless as modern math evolves other fields have sometimes needed to go back and clean up the foundations and will in the future.9 Other cases are more straightforward, with mathematicians publishing multiple proofs/patches10 or covertly correcting papers11. Sometimes they make it into textbooks: Carmichael realized that his proof for Carmichael’s totient function conjecture, which is still open, was wrong only after 2 readers saw it in his 1914112ya textbook The Theory of Numbers and questioned it. Attempts to formalize results into experimentally-verifiable results (in the case of physics-related math) or machine-checked proofs, or at least some sort of software form, sometimes turns up issues with12 accepted13 results14, although not always important (eg. the correction in 2013). Poincaré points out this mathematical version of the pessimistic induction in “Intuition and Logic in Mathematics”:

Strange! If we read over the works of the ancients we are tempted to class them all among the intuitionalists. And yet nature is always the same; it is hardly probable that it has begun in this century to create minds devoted to logic. If we could put ourselves into the flow of ideas which reigned in their time, we should recognize that many of the old geometers were in tendency analysts. Euclid, for example, erected a scientific structure wherein his contemporaries could find no fault. In this vast construction, of which each piece however is due to intuition, we may still today, without much effort, recognize the work of a logician.

… What is the cause of this evolution? It is not hard to find. Intuition can not give us rigor, nor even certainty; this has been recognized more and more. Let us cite some examples. We know there exist continuous functions lacking derivatives. Nothing is more shocking to intuition than this proposition which is imposed upon us by logic. Our fathers would not have failed to say: “It is evident that every continuous function has a derivative, since every curve has a tangent.” How can intuition deceive us on this point?

… I shall take as second example Dirichlet’s principle on which rest so many theorems of mathematical physics; today we establish it by reasonings very rigorous but very long; heretofore, on the contrary, we were content with a very summary proof. A certain integral depending on an arbitrary function can never vanish. Hence it is concluded that it must have a minimum. The flaw in this reasoning strikes us immediately, since we use the abstract term function and are familiar with all the singularities functions can present when the word is understood in the most general sense. But it would not be the same had we used concrete images, had we, for example, considered this function as an electric potential; it would have been thought legitimate to affirm that electrostatic equilibrium can be attained. Yet perhaps a physical comparison would have awakened some vague distrust. But if care had been taken to translate the reasoning into the language of geometry, intermediate between that of analysis and that of physics, doubtless this distrust would not have been produced, and perhaps one might thus, even today, still deceive many readers not forewarned.

…A first question presents itself. Is this evolution ended? Have we finally attained absolute rigor? At each stage of the evolution our fathers also thought they had reached it. If they deceived themselves, do we not likewise cheat ourselves?

We believe that in our reasonings we no longer appeal to intuition; the philosophers will tell us this is an illusion. Pure logic could never lead us to anything but tautologies; it could create nothing new; not from it alone can any science issue. In one sense these philosophers are right; to make arithmetic, as to make geometry, or to make any science, something else than pure logic is necessary.

Isaac Newton, incidentally, gave two proofs of the same solution to a problem in probability, one via enumeration and the other more abstract; the enumeration was correct, but the other proof totally wrong and this was not noticed for a long time, leading Stigler to remark:15

If Newton fooled himself, he evidently took with him a succession of readers more than 250 years later. Yet even they should feel no embarrassment. As Augustus De Morgan once wrote, “Everyone makes errors in probabilities, at times, and big ones.” (Graves, 1889137ya, page 459)

Type I > Type II?

Lefschetz was a purely intuitive mathematician. It was said of him that he had never given a completely correct proof, but had never made a wrong guess either.

Gian-Carlo Rota16

The problem with wrong proofs to correct statements is that it is hard to give a counterexample.

Case 2 is disturbing, since it is a case in which we wind up with false beliefs and also false beliefs about our beliefs (we no longer know that we don’t know). Case 2 could lead to extinction.

The prevalence of case 1 might lead us to be very pessimistic; case 1, case 2, what’s the difference? We have demonstrated a large error rate in mathematics (and physics is probably even worse off). Except, errors do not seem to be evenly & randomly distributed between case 1 and case 2. There seem to be far more case 1s than case 2s, as already mentioned in the early calculus example: far more than 50% of the early calculus results were correct when checked more rigorously. Richard Hamming (199828ya) attributes to Ralph Boas a comment that while editing Mathematical Reviews that “of the new results in the papers reviewed most are true but the corresponding proofs are perhaps half the time plain wrong”. (WP mentions as well that “His first mathematics publication was written…after he discovered an incorrect proof in another paper.”) Gian-Carlo Rota gives us an example with Hilbert:

Once more let me begin with Hilbert. When the Germans were planning to publish Hilbert’s collected papers and to present him with a set on the occasion of one of his later birthdays, they realized that they could not publish the papers in their original versions because they were full of errors, some of them quite serious. Thereupon they hired a young unemployed mathematician, Olga Taussky-Todd, to go over Hilbert’s papers and correct all mistakes. Olga labored for three years; it turned out that all mistakes could be corrected without any major changes in the statement of the theorems. There was one exception, a paper Hilbert wrote in his old age, which could not be fixed; it was a purported proof of the continuum hypothesis, you will find it in a volume of the Mathematische Annalen of the early thirties. At last, on Hilbert’s birthday, a freshly printed set of Hilbert’s collected papers was presented to the Geheimrat. Hilbert leafed through them carefully and did not notice anything.17

So only one of those papers was irreparable, while all the others were correct and fixable? Rota himself experienced this:

Now let us shift to the other end of the spectrum, and allow me to relate another personal anecdote. In the summer of 197947ya, while attending a philosophy meeting in Pittsburgh, I was struck with a case of detached retinas. Thanks to Joni’s prompt intervention, I managed to be operated on in the nick of time and my eyesight was saved. On the morning after the operation, while I was lying on a hospital bed with my eyes bandaged, Joni dropped in to visit. Since I was to remain in that Pittsburgh hospital for at least a week, we decided to write a paper. Joni fished a manuscript out of my suitcase, and I mentioned to her that the text had a few mistakes which she could help me fix. There followed twenty minutes of silence while she went through the draft. “Why, it is all wrong!” she finally remarked in her youthful voice. She was right. Every statement in the manuscript had something wrong. Nevertheless, after laboring for a while, she managed to correct every mistake, and the paper was eventually published.

There are two kinds of mistakes. There are fatal mistakes that destroy a theory; but there are also contingent ones, which are useful in testing the stability of a theory.

A mathematician of my acquaintance referred me to pg118 of The Axiom of Choice, 1973; he had found the sustained effect of the 5 footnotes humorous:

The result of Problem 11 contradicts the results announced by Levy [196363yab]. Unfortunately, the construction presented there cannot be completed.

The transfer to ZF was also claimed by Marek [196660ya] but the outlined method appears to be unsatisfactory and has not been published.

A contradicting result was announced and later withdrawn by Truss [197056ya].

The example in Problem 22 is a counterexample to another condition of Mostowski, who conjectured its sufficiency and singled out this example as a test case.

The independence result contradicts the claim of Felgner [196957ya] that the Cofinality Principle implies the Axiom of Choice. An error has been found by Morris (see Felgner’s corrections to [196957ya]).

And referred me also to the entries in the index of Fourier Analysis by Tom Körner concerning the problem of the “pointwise convergence of Fourier series”:

excessive optimism

excessive pessimism

Delambre, 473–4

general, 4, 74

Lagrange, 473

Tchebychev, 198

Some problems are notorious for provoking repeated false proofs. P=NP attracts countless cranks and serious attempts, of course, but also amusing is apparently the Jacobian Conjecture:

The (in)famous Jacobian Conjecture was considered a theorem since a 193987ya publication by Keller (who claimed to prove it). Then Shafarevich found a new proof and published it in some conference proceedings paper (in early 1950-ies). This conjecture states that any polynomial map from C^2 to C^2 is invertible if its Jacobian is nowhere zero. In 1960-ies, Vitushkin found a counterexample to all the proofs known to date, by constructing a complex analytic map, not invertible and with nowhere vanishing Jacobian. It is still a main source of embarrassment for Arxiv.org contributors, who publish about 3–5 false proofs yearly. Here is a funny refutation for one of the proofs: “Comment on a Paper by Yucai Su On Jacobian Conjecture (2005-12-30)”

The problem of Jacobian Conjecture is very hard. Perhaps it will take human being another 100 years to solve it. Your attempt is noble, Maybe the Gods of Olympus will smile on you one day. Do not be too disappointed. B. Sagre has the honor of publishing three wrong proofs and C. Chevalley mistakes a wrong proof for a correct one in the 1950’s in his Math Review comments, and I.R. Shafarevich uses Jacobian Conjecture (to him it is a theorem) as a fact…

This look into the proverbial sausage factory should not come as a surprise to anyone taking an Outside View: why wouldn’t we expect any area of intellectual endeavour to have error rates within a few orders of magnitude as any other area? How absurd to think that the rate might be ~0%; but it’s also a little questionable to be as optimistic as Anders Sandberg’s mathematician friend: “he responded that he thought a far smaller number [1%] of papers in math were this flawed.”

Heuristics

Other times, the correct result is known and proven, but many are unaware of the answers19. The famous Millennium Problems—those that have been solved, anyway—have a long history of failed proofs (Fermat surely did not prove Fermat’s Last Theorem & may have realized this only after boasting20 and neither did Lindemann21). What explains this? The guiding factor that keeps popping up when mathematicians make leaps seems to go under the name of ‘elegance’ or mathematical beauty, which widely considered important222324. This imbalance suggests that mathematicians are quite correct when they say proofs are not the heart of mathematics and that they possess insight into math, a 6th sense for mathematical truth, a nose for aesthetic beauty which correlates with veracity: they disproportionately go after theorems rather than their negations.

Why this is so, I do not know.

Outright Platonism like Gödel apparently believed in seems unlikely—mathematical expertise resembles a complex skill like chess-playing more than it does a sensory modality like vision. Possibly they have well-developed heuristics and short-cuts and they focus on the subsets of results on which those heuristics work well (the drunk searching under the spotlight), or perhaps they do run full rigorous proofs but are doing so subconsciously and merely express themselves ineptly consciously with omissions and erroneous formulations ‘left as an exercise for the reader’25.

We could try to justify the heuristic paradigm by appealing to as-yet poorly understood aspects of the brain, like our visual cortex: argue that what is going on is that mathematicians are subconsciously doing tremendous amounts of computation (like we do tremendous amounts of computation in a thought as ordinary as recognizing a face), which they are unable to bring up explicitly. So after prolonged introspection and some comparatively simple explicit symbol manipulation or thought, they feel that a conjecture is true and this is due to a summary of said massive computations.

Perhaps they are checking many instances? Perhaps they are white-box testing and looking for boundaries? Could there be some sort of “logical probability” where going down possible proof-paths yield probabilistic information about the final target theorem, maybe in some sort of Monte Carlo tree search of proof-trees, in a broader POMDP framework (eg. 2010)?26 Does sleep serve to consolidate & prune & replay memories of incomplete lines of thought, finetuning heuristics or intuitions for future attacks and getting deeper into a problem (perhaps analogous to expert iteration)?

Reading great mathematicians like Terence Tao discuss the heuristics they use on unsolved problems27, they bear some resemblances to computer science techniques. This would be consistent with a preliminary observation about how long it takes to solve mathematical conjectures: while inference is rendered difficult by the exponential growth in the global population and of mathematicians, the distribution of time-to-solution roughly matches a memoryless exponential distribution (one with a constant chance of solving it in any time period) rather than a more intuitive distribution like a type 1 survivorship curve (where a conjecture gets easier to solve over time, perhaps as related mathematical knowledge accumulates), suggesting a model of mathematical activity in which many independent random attempts are made, each with a small chance of success, and eventually one succeeds. This idea of extensive unconscious computation neatly accords with Poincaré’s account of mathematical creativity in which after long fruitless effort (preparation), he abandoned the problem for a time and engaged in ordinary activities (incubation), is suddenly struck by an answer or insight, and then verifies its correctness consciously. The existence of an incubation effect seems confirmed by psychological studies and particular the observation that incubation effects increase with the time allowed for incubation & also if the subject does not undertake demanding mental tasks during the incubation period (see 2009), and is consistent with extensive unconscious computation.

Some of this computation may happen during sleep; sleep & cognition have long been associated in a murky fashion (“sleep on it”), but it may have to do with reviewing the events of the day & difficult tasks, with relevant memories reinforced or perhaps more thinking going on. I’ve seen more than one suggestion of this, and mathematician Richard K. Guy suggests this as well.28 (It’s unclear how many results occur this way; Stanislaw Ulam mentions finding one result but never again29; J Thomas mentions one success but one failure by a teacher30; R. W. Thomason dreamed of a dead friend making a clearly false claim and published material based on his disproof of the ghost’s claim31; and Leonard Eugene Dickson reportedly had a useful dream & an early survey of 69 mathematicians yielded 63 nulls, 5 low-quality results, and 1 hit32.)

Heuristics, however, do not generalize, and fail outside their particular domain. Are we fortunate enough that the domain mathematicians work in is—deliberately or accidentally—just that domain in which their heuristics/intuition succeeds? Sandberg suggests not:

Unfortunately I suspect that the connoisseurship of mathematicians for truth might be local to their domain. I have discussed with friends about how “brittle” different mathematical domains are, and our consensus is that there are definitely differences between logic, geometry and calculus. Philosophers also seem to have a good nose for what works or doesn’t in their domain, but it doesn’t seem to carry over to other domains. Now moving outside to applied domains things get even trickier. There doesn’t seem to be the same “nose for truth” in risk assessment, perhaps because it is an interdisciplinary, messy domain. The cognitive abilities that help detect correct decisions are likely local to particular domains, trained through experience and maybe talent (ie. some conformity between neural pathways and deep properties of the domain). The only thing that remains is general-purpose intelligence, and that has its own limitations.

Leslie Lamport advocates for machine-checked proofs and a more rigorous style of proofs similar to natural deduction, noting a mathematician acquaintance guesses at a broad error rate of 1⁄333 and that he routinely found mistakes in his own proofs and, worse, believed false conjectures34.

We can probably add software to that list: early software engineering work found that, dismayingly, bug rates seem to be simply a function of lines of code, and one would expect diseconomies of scale. So one would expect that in going from the ~4,000 lines of code of the Microsoft DOS operating system kernel to the ~50,000,000 lines of code in Windows 2003 (with full systems of applications and libraries being even larger: the comprehensive Debian repository in 200719ya contained ~323,551,126 lines of code) that the number of active bugs at any time would be… fairly large. Mathematical software is hopefully better, but practitioners still run into issues (eg. et al 2014, et al 2017) and I don’t know of any research pinning down how buggy key mathematical systems like Mathematica are or how much published mathematics may be erroneous due to bugs. This general problem led to predictions of doom and spurred much research into automated proof-checking, static analysis, and functional languages35.

The doom, however, did not manifest and arguably operating systems & applications are more reliable in the 2000s+ than they were in the 1980–10199036yas36 (eg. the general disappearance of the Blue Screen of Death). Users may not appreciate this point, but programmers who happen to think one day of just how the sausage of Gmail is made—how many interacting technologies and stacks of formats and protocols are involved—may get the shakes and wonder how it could ever work, much less be working at that moment. The answer is not really clear: it seems to be a combination of abundant computing resources driving down per-line error rates by avoiding optimization, modularization reducing interactions between lines, greater use of testing invoking an adversarial attitude to one’s code, and a light sprinkling of formal methods & static checks37.

While hopeful, it’s not clear how many of these would apply to existential risks: how does one use randomized testing on theories of existential risk, or tradeoff code clarity for computing performance?

Type I vs Type II

So we might forgive case 1 errors entirely: if a community of mathematicians take an ‘incorrect’ proof about a particular existential risk and ratify it (either by verifying the proof subconsciously or seeing what their heuristics say), it not being written out because it would be too tedious38, then we may be more confident in it39 than lumping the two error rates together. Case 2 errors are the problem, and they can sometimes be systematic. Most dramatically, when an entire group of papers with all their results turn out to be wrong since they made a since-disproved assumption:

In the 1970s and 1980s, mathematicians discovered that framed manifolds with Arf-Kervaire invariant equal to 1—oddball manifolds not surgically related to a sphere—do in fact exist in the first five dimensions on the list: 2, 6, 14, 30 and 62. A clear pattern seemed to be established, and many mathematicians felt confident that this pattern would continue in higher dimensions…Researchers developed what Ravenel calls an entire “cosmology” of conjectures based on the assumption that manifolds with Arf-Kervaire invariant equal to 1 exist in all dimensions of the form 2n − 2. Many called the notion that these manifolds might not exist the “Doomsday Hypothesis,” as it would wipe out a large body of research. Earlier this year, Victor Snaith of the University of Sheffield in England published a book about this research, warning in the preface, “…this might turn out to be a book about things which do not exist.”

Just weeks after Snaith’s book appeared, Hopkins announced on April 21 that Snaith’s worst fears were justified: that Hopkins, Hill and Ravenel had proved that no manifolds of Arf-Kervaire invariant equal to 1 exist in dimensions 254 and higher. Dimension 126, the only one not covered by their analysis, remains a mystery. The new finding is convincing, even though it overturns many mathematicians’ expectations, Hovey said.40

The parallel postulate is another fascinating example of mathematical error of the second kind; its history is replete with false proofs even by greats like Lagrange (on what strike the modern reader as bizarre grounds)41, self-deception, and misunderstandings—Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri developed a non-Euclidean geometry flawlessly but concluded it was flawed:

The second possibility turned out to be harder to refute. In fact he was unable to derive a logical contradiction and instead derived many non-intuitive results; for example that triangles have a maximum finite area and that there is an absolute unit of length. He finally concluded that: “the hypothesis of the acute angle is absolutely false; because it is repugnant to the nature of straight lines”. Today, his results are theorems of hyperbolic geometry.

We could look upon Type II errors as having a benevolent aspect: they show both that our existing methods are too weak & informal and that our intuition/heuristics break down at it—implying that all previous mathematical effort has been systematically misled in avoiding that area (as empty), and that there is much low-hanging fruit. (Consider how many scores or hundreds of key theorems were proven by the very first mathematicians to work in the non-Euclidean geometries!)

Future Implications

Should such widely-believed conjectures as P ≠ NP42 or the Riemann hypothesis turn out be false, then because they are assumed by so many existing proofs, entire textbook chapters (and perhaps textbooks) would disappear—and our previous estimates of error rates will turn out to have been substantial underestimates. But it may be a cloud with a silver lining: it is not what you don’t know that’s dangerous, but what you know that ain’t so.

See Also

External Links

“The Black Hole Case: The Injunction Against the End of the World”, 2009

“The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences”, 1960; “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics”, Richard 1980

“LA-602: Ignition of the Atmosphere with Nuclear Bombs” (“LA-602 versus RHIC Review”)

Responses:

“Flaws in the Perfection” -(Anders Sandberg commentary on this essay)

“There’s more to mathematics than rigor and proofs”, Terence Tao

“Mathematical Proofs Improve But Don’t Guarantee Security, Safety, and Friendliness” (Luke Muehlhauser)

“The probabilistic heuristic justification of the ABC conjecture” (Terence Tao)

“Could We Have Felt Evidence For SDP ≠ P?” (see particularly “Bad Guesses”)

“Have any long-suspected irrational numbers turned out to be rational?”; “Mathematical ‘urban legends’”; “Examples of falsified (or currently open) long-standing conjectures leading to large bodies of incorrect results”; “What mistakes did the Italian algebraic geometers actually make?”; “Why doesn’t mathematics collapse down, even though humans quite often make mistakes in their proofs?”; “Most interesting mathematics mistake?”

“Cosmic Rays: what is the probability they will affect a program?” or GUIDs

“Another Look at Provable Security”; “Best Practices: Formal Proofs, the Fine Print and Side Effects”, Murray & van 2018

“Burn-in, bias, and the rationality of anchoring”, et al 2012; “Where Do Hypotheses Come From?”, et al 2017

“Fast-key-erasure random-number generators”, Dan Bernstein

“Proofs shown to be wrong after formalization with proof assistant?”

“Problem Solving”, 1957

“Bloom filters debunked: Dispelling 30 Years of bad math with Coq!” (“The widely cited expression for the false positive rate of a bloom filter is wrong! In fact, as it turns out, the behaviors of a Bloom filter have actually been the subject of 30 years of mathematical contention, requiring multiple corrections and even corrections of these corrections.”)

“When Extrapolation Fails Us: Incorrect Mathematical Conjectures [About Very Large Numbers]”

“Patterns that Eventually Fail” (on Borwein integrals: 2001; 2 × cos(t) example from 2014); “How They Fool Ya”, 3Blue1Brown

“Mathematical Proof Between Generations”, et al 2022

“What Makes Mathematicians Believe Unproven Mathematical Statements?”, 2023

Appendix

1998

“A credo of sorts”; Vaughan Jones (Truth in Mathematics, 199828ya), pg208–209:

Proofs are indispensable, but I would say they are necessary but not sufficient for mathematical truth, at least truth as perceived by the individual.

To justify this attitude let me invoke two experiences of current mathematics, which very few mathematicians today have escaped.

The first is computer programming. To write a short program, say 100 lines of C code, is a relatively painless experience. The debugging will take longer than the writing, but it will not entail suicidal thoughts. However, should an inexperienced programmer undertake to write a slightly longer program, say 1,000 lines, distressing results will follow. The debugging process becomes an emotional nightmare in which one will doubt one’s own sanity. One will certainly insult the compiler in words that are inappropriate for this essay. The mathematician, having gone through this torture, cannot but ask: “Have I ever subjected the proofs of any of my theorems to such close scrutiny?” In my case at least the answer is surely “no”. So while I do not doubt that my proofs are correct (at least the important ones), my belief in the results needs bolstering. Compare this with the debugging process. At the end of debugging we are happy with our program because of the consistency of the output it gives, not because we feel we have proved it correct—after all we did that at least twenty times while debugging and we were wrong every time. Why not a twenty-first? In fact we are acutely aware that our poor program has only been tested with a limited set of inputs and we fully expect more bugs to manifest themselves when inputs are used which we have not yet considered. If the program is sufficiently important, it will be further debugged in the course of time until it becomes secure with respect to all inputs. (With much larger programs this will never happen.) So it is with our theorems. Although we may have proofs galore and a rich surrounding structure, if the result is at all difficult it is only the test of time that will cause acceptance of the “truth” of the result.

The second experience concerning the need for supplements to proof is one which I used to dislike intensely, but have come to appreciate and even search for. It is the situation where one has two watertight, well-designed arguments—that lead inexorably to opposite conclusions. Remember that research in mathematics involves a foray into the unknown. We may not know which of the two conclusions is correct or even have any feeling or guess. Proof at this point is our only arbiter. And it seems to have let us down. I have known myself to be in this situation for months on end. It induces obsessive and anti-social behavior. Perhaps we have found an inconsistency in mathematics. But no, eventually some crack is seen in one of the arguments and it begins to look more and more shaky. Eventually we kick ourselves for being so utterly stupid and life goes on. But it was no tool of logic that saved us. The search for a chink in the armour often involved many tricks including elaborate thought experiments and perhaps computer calculations. Much structural understanding is created, which is why I now so value this process. One’s feeling of having obtained truth at the end is approaching the absolute. Though I should add that I have been forced to reverse the conclusion on occasions…

Unreliability of Programs

I have never written an equation or line of code that I was 100% confident of, or which I thought had less than a 1-in-trillions chance of it being wrong in some important way. Software & real-world systems are too complex & fragile.

Every part of my understanding, the hardware, or the real-world context is less reliable than 1-in-trillions.

Let’s consider potential problems with our understanding of even the most trivial seeming arithmetic comparison checking that ‘x + x = 2x’…

Numbers that fool the Fermat primality test are called Carmichael numbers, and little is known about them other than that they are extremely rare. There are 255 Carmichael numbers below 100,000,000…In testing primality of very large numbers chosen at random, the chance of stumbling upon a value that fools the Fermat test is less than the chance that cosmic radiation will cause the computer to make an error in carrying out a ‘correct’ algorithm.

Considering an algorithm to be inadequate for the first reason but not for the second illustrates the difference between mathematics and engineering.

Hal Abelson & Gerald Sussman (Structure And Interpretation of Computer Programs)

Consider a simple-seeming line of conditional code for the arithmetical tautology: x + x == 2*x. How could this possibly ever go wrong? Well…

Where did you initialize x? Was it ever initialized to a non-null value?

(Or has it been working accidentally because it uses uninitialized memory which just happened to have a workable value?)

Is this comparison by reference, equality, hash, or some other way entirely?

Which integer type is this? Does that integer type overflow?

In some languages, x might be a string being parsed as a number. (JavaScript is infamous for this due to its type coercion and redefining operators; this will evaluate to

true:x = "1"; 2*x == 2 && x + x == "11";.)In highly dynamic or object-oriented languages,

+,==, and*could all have been redefined per x and mean… just about anything, and do anything as side-effects of methods like getters.homoglyph attack: ‘x’ might not be ‘х’… because the second one is actually a different letter (CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER HA)

“Trojan Source” attack: OK, you are sure ‘x’ is in fact ‘x’; but are you reading the right ‘x’? What you think is a line of source code might actually be a commented out line, and the comment is the source code, due to Unicode right-to-left/bidirectional characters

Does multiplying integers like this potentially trigger undefined behavior and arbitrary compiler ‘optimizations’?

If it can never overflow because it’s a “big int” with arbitrary-precision arithmetic, how much RAM does this allocate? What happens if the result is larger than fits in RAM? (How would evaluation order like laziness affect this?)

How much do you know about your big-integer library to begin with? (They do have bugs, like all software.)

If this is floating point (do you know for sure?), won’t this usually be false at larger/smaller numbers?

What about floating point rounding or other exotic modes?

Or multiplying special values like NaN or +Inf vs −Inf?

If you know about all this and really did want that… how sure are you that the compiler isn’t incorrectly equationally-reasoning that they are equal and rewriting them behind your back?

Did the compiler optimization away this check entirely because “obviously” it is true?

What is the operator precedence of this code?

By the way, are you sure it’s a conditional at all? Perhaps it was parsed as

(x + x == 2) * x?Preprocessor/macro-expansion problems: In C,

xmight be a macro that expands to an expression with side effects, evaluated a different number of times on each side. Or2*xmight lack parenthesization:#define x 1+1makes2*xevaluate to 3.

What is the evaluation order of this code?

This is serial-threaded code, right? No parallelism anywhere? If there is…

Signal handlers can interrupt your code and change stuff. So your code is de facto concurrent anyway. Oh, but you solved that? So there’s no more parallelism.

Trick question: you thought there wasn’t, but there was anyway because all systems are inherently parallel now. So there are dangers around cache coherency & races, leading to many classes of attacks/errors like Spectre.

And x here can change: the direct way of computing it would involve at least 5 values being stored & referenced somewhere. (The 3 written x in the equation, then the sum of two, and then the multiplied version.)

Are you running the right code at all? Maybe you’re running a cached binary, the build system didn’t rebuild the code, you are in the wrong working directory or the wrong VCS branch…

How likely is your computation to be corrupted or subverted by an attacker doing something like a buffer overflow attack or a row hammer attack, which winds up clobbering your x?

What happens if the computer halts or freezes or is DoSed or the power goes out halfway through the computation?

Why do you believe the hardware will always store & execute everything correctly?

“Neo, you think that’s real hardware you’re running on?” And VMs can be buggy and implement stuff like floating point incorrectly, of course.

What are the odds that the hardware will be hit by a cosmic ray during any of these operations? Even ECC RAM is increasingly unreliable.

Or that your RAM has a permanent fault in it?

(For several years, compiling this website would occasionally result in strange segfaults in apparently correct regexp code; this turned out to be a bad RAM chip where ordinary RAM use simply didn’t stress it enough.)

What are the odds that the CPU core in question is sometimes unable to add or multiply correctly? (If you’re a hyperscaler, they exist in your fleet of servers somewhere!)

What are the odds you will discover another Pentium FDIV bug?

How do you know all instances of x were never corrupted anywhere during storage or transmission?

I can safely say that in my programming life, I have written many fewer than trillions of lines of code, and I have made many more of these errors than 0.

So I infer that for even the simplest-seeming code, I am unable to write code merely as reliable as a 1-in-trillions error rate.