|

WatergateAt the end of the day, Watergate will probably be remembered best as the political scandal that caused the suffix "-gate" to be senselessly appended to every political scandal that followed it.

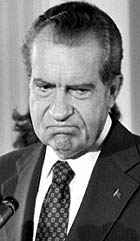

President Richard M. Nixon had always been a polarizing figure, from his earliest days in Congress as a henchman to Commie-hunting Senator Joseph McCarthy, to his scandal-tainted tenure as vice president under Dwight Eisenhower, when his political career was saved only by brandishing a small dog in front of a television camera. So everyone pretty much knew Nixon was a mean, crazy fuck. Unfortunately, this intellectual understanding didn't translate itself into a visceral experience until Watergate erupted onto the front pages, by which time it was too late. In 1969, Nixon rode into office with the resounding approval of what he called the "Silent Majority," so named because it possibly didn't actually exist. He inherited the Vietnam War, among other things, and busied himself attempting to end the war "with honor" using a "secret plan" which was later shockingly discovered also to not have existed. Nixon was feeling edgy about his political enemies and his reelection chances as 1972 drew near. He needn't have worried. His opponent, George McGovern, couldn't have campaigned his way out of a paper bag. But in 1971, Nixon's paranoia was sharpened by the release of the "Pentagon papers," a leaked series of documents containing various unsavory secrets about the Vietnam War.

The PlumbersYou don't get to be known as "Tricky Dick" by sitting around waiting for your enemies to attack. Nixon put together a shady group of operatives known as "The Plumbers," who were given the job of stopping leaks (get it?).The Plumbers quickly proved themselves to be a far greater detriment to the country than any crummy leak. The group included E. Howard Hunt, a disgruntled former CIA operative, possible assassin of John F. Kennedy and author of bad spy novels; and G. Gordon Liddy, a raving psychopath and former FBI agent. Among the Plumbers' exploits was the 1971 burglary of a psychiatrist's office, where they were trying to dig up dirt on a poor schmuck named Daniel Ellsberg, who had cemented his place in history by leaking the Pentagon Papers, but whose name would tragically be attached to the words "psychiatrist's office" for the rest of his life. The Plumbers made their big mistake in 1972, when a team of mostly Cubans was caught breaking into the Democratic Party's national headquarters in the Watergate Hotel (a location which would later be called "home" by Bob Dole and Monica Lewinsky). The story of the Plumbers' arrest was broken in the Washington Post, of course, by that immortal and celebrated hero of journalism, Alfred E. Lewis.

Then, a couple days later, two nobodies named Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein got hold of the story, which changed everything, mostly because of their remarkable resemblance to Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman. Woodward and Bernstein stumbled onto a tiny detail that Alfred E. Lewis had somehow missed (say it ain't so!), namely that a former CIA spook named James McCord was among the men arrested at the Watergate. McCord's current job was working for the very unfortunately named "Committee to Re-Elect the President," aka CREEP. By August, the Washington Post had tied CREEP to the Plumbers through diverted funds, which were controlled by former Attorney General John Mitchell. When Carl Bernstein called Mitchell for comment, the head of Nixon's election campaign responded famously: "[Post Publisher] Katie Graham's gonna get her tit caught in a big fat wringer if that's ever published." In October, the Post reported that the break-in was part of a massive campaign of spying and sabotage being carried out by Republicans on behalf of the Nixon administration. The American people were outraged, needless to say, and they showed their fury by viciously and savagely re-electing Nixon in a historic landslide. That'll teach the bastard!

The Noose TightensMcCord was convicted in early 1973, and the four other Watergate burglars entered guilty pleas. Liddy was convicted; Hunt entered a guilty plea.Had the whole thing stopped there, Watergate would simply have been the worst scandal in the history of American presidential politics and an appalling abuse of the powers vested in the Executive Branch. But of course, it didn't stop there. In fact, it just kept getting worse and worse. Because, behind the scenes, the Nixon White House was in this mess up to their eyeballs, to an extent that was still inconceivable to anyone on the outside. As the story continued to unfold, it quickly became clear that the "President's Men" had been directly involved in the Plumbers' actions, as McCord started naming names, including top Nixon adviser John Erlichmann and White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, Nixon lawyer Charles Colson, Nixon campaign chief John Mitchell, deputy campaign manager Jeb Magruder and White House Counsel John Dean.

In March 1973, Dean went to the president and initiated a self-serving conversation in which he told the president "There's no doubt about the seriousness of the problem we're, we've got. We have a cancer within, close to the Presidency, that's growing. It's growing daily. It's compounding, it grows geometrically now because it compounds itself." Dean went on to tell Nixon that some of the people connected to the Watergate mess including specifically Hunt were threatening to talk unless they were paid hush money. Some money had already been paid, and Dean told Nixon he could expect the shakedown to continue. Nixon already knew all this stuff; Dean's objective in this meeting was to create a good-looking centerpiece for his eventual testimony. After all, the Senate had already been running nationally televised hearings on the Watergate scandal, and by April, the writing was on the wall. After the "cancer on the presidency" conversation, Dean started seriously pursuing CYA as a way of life. By the time Jeb Magruder implicated Dean in the break-in, the White House counsel had already put word out on the street that he was willing and able to implicate the president.

After Dean and Co. were cut loose, it was clear that the normal functions of law enforcement were not well-suited to investigating the President of the United States. Newly appointed Attorney General Elliott Richardson took the unprecedented step of naming a special prosecutor to investigate the president, a distinguished legal scholar named Archibald Cox. Nixon appointed Alexander Haig, an aide to Henry Kissinger, to take over the role of White House Chief of Staff.

The TapesThroughout the spring, the depth and breadth of the Watergate problem started to take shape for the public. An elaborate web of deception began to emerge, and it was clear that the president's closest advisers had been up to dirty dealings indeed. The key crimes in Watergate included:

Until July 1973, Dean's testimony was treated largely as a case of one disgruntled employee's word against the word of the President of the United States. But all hell broke loose on July 13, when insignificant presidential minion Alexander Butterfield let slip the secret of the century: President Nixon had a secret taping system installed in the White House, which recorded every conversation held in the Oval Office. As political bombshells go, this still ranks among the biggest and best. It instantly transformed the scandal rocking the Nixon administration by dangling the prospect of conclusive evidence.

It would have looked awful, but there were half a dozen reasonably plausible rationales that could have been concocted to justify the move, which would likely have eliminated any chance investigators would ever find a "smoking gun" irrefutably implicating the president in the Watergate mess. For reasons destined to remain one of history's greatest mysteries, Nixon let the tapes be. Haig ordered the taping system shut down immediately, but that hardly mattered. It was far too late to help things. By the end of the July, both the Senate committee and the special prosecutors were salivating over the tapes. Nixon refused to turn the tapes over willingly, so both the committee and Cox issued subpoenas. This set the stage for an all-out battle between the executive, legislative and judicial branches of government, the likes of which had never been seen before or since.

The Constitutional CrisisBehind the scenes, top Nixon officials were in a state of panic. The president issued a statement making it painfully clear that he would not acknowledge the legitimacy of any court order that he turn over the documents, which meant the case was headed for the Supreme Court and a genuine constitutional crisis.Even more unclear was the question of whether Nixon would allow compliance with a Supreme Court order. The president's aides were forced to consider lurid worst-case scenarios, such as an armed squad of U.S. Marshals arriving at the White House to collect the tapes on orders from the Supreme Court, only to be barred at the gate by armed U.S. soldiers taking orders from the commander-in-chief. Nixon insisted the tapes were protected by "executive privilege," a non-Constitutional premise which had wormed its way into court precedent over the years, although never in such a dramatic context. He also maintained steadfastly that nothing on the tapes contradicted his insistence that neither he nor his top aides knew anything about Watergate or the ensuing coverup. Cox wasn't buying the "executive privilege" argument and continued aggressively pursuing the president, his flunkies and the tapes. By October, Nixon decided he'd had enough and made perhaps the worst decision of his presidency. In what would later become known as the "Saturday Night Massacre," Nixon decided that as president he didn't have to take all this crap. He instructed Attorney General Elliott Richardson to fire Cox and close the office of the special prosecutor. Richardson refused to comply with the order and resigned. Nixon then ordered Deputy Attorney General William Ruckleshaus to fire Cox. Ruckleshaus also refused the order, and resigned. Solicitor General (and future Supreme Court nominee) Robert Bork was next in line. Bork complied with the order. FBI agents were sent to the Justice Department on Nixon's orders to secure the premises and make sure none of the departing officials or staffers attempted to remove any documents or copies on their way out the door. Cox's offices were sealed. The massacre devastated Washington, D.C. No one had ever seen anything even remotely approaching this. The president was widely seen as defying the laws of the land to protect himself. In November, Nixon was forced to replace Cox after a massive public outcry. He brought in Texas lawyer Leon Jaworski to take over the Watergate investigation. Jaworski was politically invulnerable after the disaster of the Saturday night massacre. That month, Nixon made an extraordinary public statement, a lie that would eventually come to define his presidency, when he told the American people, "I am not a crook." In December, the crisis continued to heighten. Nixon had presented a plan by which the White House would provide edited transcripts of the subpoenaed Watergate tapes, which he (and only he) thought would satisfy the demands of the subpoenas, which hadn't gone away despite the firings. During the course of this process, it came out that one of the tapes had an 18 and a half minute gap, where a presidential conversation had been erased, provoking a new storm of controversey. No one has ever explained the gap, although Nixon tried to pin it on a clerical error by his secretary at the time. Alexander Haig suggested some "sinister force" was behind the erasure.

Richard M. Nixon was secretly named by the grand jury as an "unindicted co-conspirator" in the cover-up. In April, Nixon turned over 1,200 pages of edited transcripts from some of the subpoenaed tapes. The disclosures proved the worst of all worlds. Aside from immortalizing the phrase "expletive deleted," the editing of the transcripts made them entirely unsatisfactory to the various investigations. Even more disturbing was the fact that even the edited transcripts failed to clear Nixon in the least. In fact, they implicated him even more deeply, depicting conversations in which Nixon talked to aides about how to raise money to pay blackmailers, using presidential powers to commute the sentences of conspirators and discussing ways in which "national security" could be invoked to protect defendants. If these were the edited tapes, everyone began to wonder just what the flying fuck was on the unedited tapes. Shortly thereafter, Erlichmann and Liddy were convicted on charges related to the Ellsberg break-in. By July, there was no escaping the ramifications of the tapes and the continuing series of convictions against the president's top aides. The Supreme Court ordered Nixon to turn over the tapes, and the House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment.

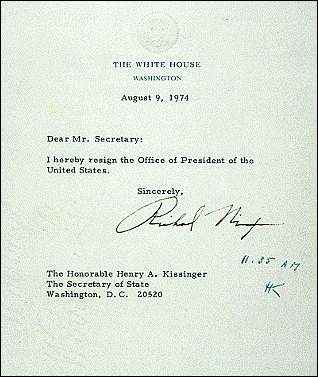

The ResignationIn August, Nixon faced the music. In a televised address to the nation, he tendered his resignation amid a final flurry of self-serving lies. The following excerpts are annotated for your convenience:

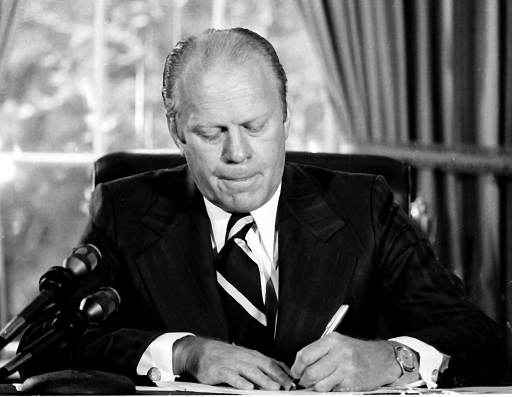

The AftermathNixon left the White House the next day, August 9, 1974. He was pardoned by his successor, Gerald Ford, one month later.

Americans were deeply disturbed to find out that their president was pretty much the same as their crazy black-sheep uncles and/or themselves, and they never really lived it down. Woodward and Bernstein went on to become famous movie stars. The identity of "Deep Throat," the top-secret anonymous source who steered the reporters toward many of their scoops, was revealed in 2005 to be W. Mark Felt, the No. 2 official at the FBI. The revelation was somewhat anticlimactic, especially since Carl Bernstein's son had blabbed the secret to his buddies at summer camp a few years earlier. Archibald Cox and Leon Jaworski went on to become folk heroes for about five minutes, after which they were forgotten. Just about everyone else in this story went to jail, and pretty much all of them are back on the streets and/or dead today. Except for Ford, that is, who served out the remainder of Nixon's presidency and was trounced in 1976 by Democrat Jimmy Carter. Carter ran on a platform of "honesty" and was apparently the only president in American history to actually mean it. See where it got him... Richard Nixon died April 23, 1994. If he had lived just four more years, he would have had the grim satisfaction of watching President Bill Clinton get impeached over a blow job. To the best of anyone's knowledge, Katie Graham's tits were just fine until her death in 2001, may they rest in peace.

Timeline

|

Well, OK, that and a genuine political crisis. Unlike the

Well, OK, that and a genuine political crisis. Unlike the  Although some small controversy still surrounds the purpose of the visit, it's generally thought they were there planting bugs and other surveillance equipment in order to spy on the Democrats. The reason for this theory is that they were pretty much caught in the act, holding a bunch of bugging and spying equipment.

Although some small controversy still surrounds the purpose of the visit, it's generally thought they were there planting bugs and other surveillance equipment in order to spy on the Democrats. The reason for this theory is that they were pretty much caught in the act, holding a bunch of bugging and spying equipment.  Unfortunately for Nixon, Dean was a different breed from the slavishly loyal Erlichmann and Haldeman. Dean had been a key player in staging the Watergate break-in; he had also briefed Nixon about the incident on the same day the burglars were arrested.

Unfortunately for Nixon, Dean was a different breed from the slavishly loyal Erlichmann and Haldeman. Dean had been a key player in staging the Watergate break-in; he had also briefed Nixon about the incident on the same day the burglars were arrested.  On April 27, FBI director Patrick Grey resigned after it became clear he had destroyed evidence provided to him by Dean. On April 30, in an effort at damage control, Nixon fired Dean, Erlichmann, Haldeman and Attorney General Richard Kleindienst.

On April 27, FBI director Patrick Grey resigned after it became clear he had destroyed evidence provided to him by Dean. On April 30, in an effort at damage control, Nixon fired Dean, Erlichmann, Haldeman and Attorney General Richard Kleindienst.  At this point, one might think that Nixon would have immediately burned all the tapes. In retrospect, numerous analyses of the Watergate scandal have concluded that if Nixon (or his selected fall guy within the administration) had destroyed all the tapes the moment their existence was made public, it could very well have saved his presidency.

At this point, one might think that Nixon would have immediately burned all the tapes. In retrospect, numerous analyses of the Watergate scandal have concluded that if Nixon (or his selected fall guy within the administration) had destroyed all the tapes the moment their existence was made public, it could very well have saved his presidency.  The situation continued to drag on for months as Nixon stalled under the pretext of reviewing and transcribing the tapes. In March, a grand jury indicted Mitchell, Haldeman and Erlichmann for conspiring to obstruct the investigation of Watergate.

The situation continued to drag on for months as Nixon stalled under the pretext of reviewing and transcribing the tapes. In March, a grand jury indicted Mitchell, Haldeman and Erlichmann for conspiring to obstruct the investigation of Watergate.  "I would have preferred to carry through to the finish (true) whatever the personal agony it would have involved, and my family unanimously urged me to do so (lie). But the interest of the Nation must always come before any personal considerations (lie).

"I would have preferred to carry through to the finish (true) whatever the personal agony it would have involved, and my family unanimously urged me to do so (lie). But the interest of the Nation must always come before any personal considerations (lie). "As he assumes that responsibility, he will deserve the help and the support of all of us (true). As we look to the future, the first essential is to begin healing the wounds of this Nation, to put the bitterness and divisions of the recent past behind us (true but self-serving), and to rediscover those shared ideals that lie at the heart of our strength and unity as a great and as a free people (more or less true).

"As he assumes that responsibility, he will deserve the help and the support of all of us (true). As we look to the future, the first essential is to begin healing the wounds of this Nation, to put the bitterness and divisions of the recent past behind us (true but self-serving), and to rediscover those shared ideals that lie at the heart of our strength and unity as a great and as a free people (more or less true). Most of the notorious tapes were eventually released. They revealed a president deeply steeped in the illegal activities of his underlings, a president who was openly racist and prone to rants about Jews and blacks, a president who swore an awful lot, a president who was deeply paranoid and liked nothing better than to fume and plot regarding his numerous enemies (real and imagined).

Most of the notorious tapes were eventually released. They revealed a president deeply steeped in the illegal activities of his underlings, a president who was openly racist and prone to rants about Jews and blacks, a president who swore an awful lot, a president who was deeply paranoid and liked nothing better than to fume and plot regarding his numerous enemies (real and imagined).