|

Unamerican Activities

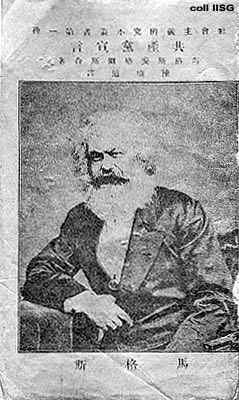

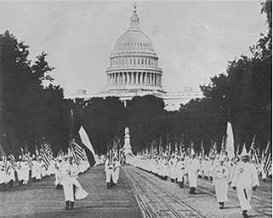

The War Against Communism gave us many wonderful things: The space program, satellite TV, a neurotic obsession with Armageddon, Richard M. Nixon, the Plumbers, Ronald Reagan, aerosolized anthrax, ultra-secret death rays, Osama bin Laden, and, of course, the House Un-American Activities Committee, sometimes known by the vacuum cleaner-like acronym, HUAC. Communism existed long before there was ever a committee to investigate it. In one form or another, communism (with a lowercase c) dates back to the earliest written histories, and probably even much earlier, since many tribal systems are communal. The modern form of communism was born in 1848, with the publication of the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Engels was obscured by the rising currency of Marx, a German Jew who somehow became the national hero of the Soviet Union, which was not known for being particularly fond of either Germans or Jews. Marx became closely associated with such evil communist credos as "Workers of the world unite; you have nothing to lose but your chains" and "From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs." Clearly, his was a diabolical genius. Communism and its kissing cousin, socialism, were not especially considered national enemies until the 1917 Russian Revolution, in which the tsars and the tsarists were tossed out in favor of the Communists, with a capital C, leaving Vladimir Lenin as absolute dictator once the smoke eventually cleared. As leader of Russia, Lenin abolished private property and outlawed religion, which made some in the United States nervous. That nervousness became consternation when Lenin died and was replaced by Josef Stalin, who cherry-picked the writings of Marx in order to justify an ever more despotic dictatorship. He murdered his rivals, oppressed his people, built up his army and signed a nonaggression pact with Adolf Hitler.

A Republican named J. Parnell Thomas guided HUAC after the war was over, and he established a principle that Republican politicians would follow for years to come: "When in doubt, blame Hollywood." This credo put HUAC on the map in 1947, when the Committee called more than 40 prominent American screenwriters, producers and other artists to testify about their Un-American leanings. The witnesses saw a pattern quickly emerged: It was easy to be a good American. All you had to do was point out how good you were compared to bad Americans, as long as you could identify those bad Americans by name. The witnesses were good Americans. They named names. What had begun as just another House committee performing just another meaningless task as government committees are wont to do, quickly turned into a star-studded battle royale. As the Committee called more and more Hollywood bigwigs to testify, the headlines became larger and more frequent. HUAC's profile became even higher when Hollywood began to fight back. Through the naming of names, HUAC identified eleven witnesses who were considered "hostile," i.e., they were suspected of being Communists and thus of fighting to destroy everything that made America great. Bertolt Brecht, a highly regarded German playwright, fled the country rather than face the Committee, leaving a group that would become infamous as the Hollywood Ten. The ten were:

You may have noticed two major common elements among the Ten. Most of them were involved in writing film noir, a 1940s movie genre that glamorized decadence and encouraged a distrust of authority, and most of them were involved in writing 1940s "war movies," which was not so much a film genre as a U.S. government-subsidized propaganda campaign of drippingly patriotic garbage the likes of which has never been seen before or since. A grateful nation gives its thanks. Outraged by what it saw as the

persecution of these writers, a group of high-profile Hollywood bigshots

led by Humphrey Bogart organized a protest to the committee's

inquisition, only to retreat in shame when some of the Hollywood Ten HUAC had marshalled the awesome power of the U.S. Congress to destroy the lives of a few patriotic Americans, but this was only the beginning. The blacklist was expanded to include many Hollywood luminaries whose names were given up by witnesses under pressure, including such dangerous criminals as Leonard Bernstein, Charlie Chaplin, Dashiell Hammett, Burl Ives, Arthur Miller and Orson Welles. Some blacklistees saw their careers ended; others survived by working as expatriates or simply riding out the storm. In 1947, Walt Disney appeared before HUAC to rat out his fellow artists. Disney boasted of his record producing pro-U.S. propaganda (despite the fact that some of the Hollywood Ten had more impressive resumes on this front) and insisted that everyone at his company was "100 percent American." He blamed Disney Co.'s labor relations problems on Communists and fingered several former employees as pinko rats that he smoked out and disposed of.

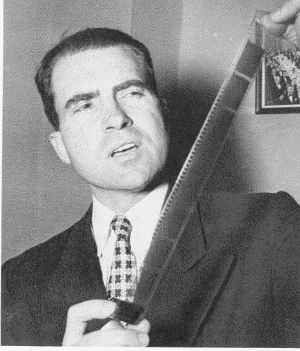

In 1948, HUAC enjoyed its greatest triumph when it nailed a former State Department employee named Alger Hiss to the wall. Whittaker Chambers, a confessed Communist spy turned red-baiting journalist, implicated Hiss as a Soviet agent. In a dramatic piece of theater, Chambers led HUAC investigators to a pumpkin patch, where he revealed two rolls of film inside a hollowed-out pumpkin. The film contained images of State Department documents Hiss had allegedly copied for his Soviet masters.

An investigation of the film rolls revealed that they were made in 1945, but the documents were supposedly photographed in 1938. It also turned out that Chambers had actually put the film into the pumpkins in the first place. Chambers claimed the documents were authentic, however, saying they had been saved from his days as a Commie spy. Nixon was furious, but recovered quickly when a follow-up investigation of the film conveniently confirmed the original date. Speaking later on his famous White House tapes, Nixon explained his law enforcement strategy for anyone who had missed it: "We won the Hiss case in the papers. We did. I had to leak stuff all over the place. Because the Justice Department would not prosecute it. Hoover didn't even cooperate. It was won in the papers. We have to develop a program, a program for leaking out information. We're destroying these people in the papers."

An Un-American epidemic was clearly brewing by this time, and despite Nixon's star turn, the House of Representatives was strictly bush league. The main focus of the anti-Communist movement shifted to the Senate in 1950, when Joseph McCarthy infamously charged that Communists had infiltrated the State Department. McCarthy was a member of the Senate's Government Operations Committee (GOC), another version of the anti-Communist inquisition, and he pressed for an investigation of these alleged State Department spies. When another Senate committee investigated the charges and branded them fraudulent, McCarthy was undeterred.

In 1953, McCarthy became chairman of the GOC, marking the official launch of perhaps the ugliest period in American history, one that would forever bear his name. The GOC and HUAC launched a series of public hearings in which witnesses were challenged to refute allegations that came in over the transom, usually unsourced and largely unfounded. Witnesses were denied due process, harassed and threatened with prison if their answers didn't please the committees. Among the luminaries summoned to testify before the twin hearings were composer Aaron Copland and poet Langston Hughes. J. Robert Oppenheimer, father of the U.S. H-bomb, was targeted by the FBI and by McCarthy for his alleged Soviet sympathies and security breaches. As these examples showed, McCarthy and HUAC took a perverse pleasure in attacking individuals who had performed extraordinary services for their country, or who would, in the years ahead, become almost iconic examples of America. The Oppenheimer case was only one of many in which the FBI and McCarthy collaborated to harass "subversives." J. Edgar Hoover had a lot in common with Roy Cohn, one of McCarthy's top aides. Both were ultra-closeted, self-loathing homosexuals who didn't hesitate to exploit any sign of questionable sexuality in their enemies as evidence of commie pinko leanings. Outwardly a raving homophobe, McCarthy himself was rumored to be gay. Between the three of them, the U.S. government spent nearly as much time outing and censuring gays as it did Communists.

McCarthy reciprocated by sharing the names he gathered in secret sessions where he battered witnesses with ominous but vague threats. Although McCarthy made a lot of noise about treason, no one was ever sent to prison for refusing to answer his questions.

After terrorizing much of the civilian bureaucracy in Washington, McCarthy turned his attention to the Army. With a retired general in the White House, the decision to attack the army proved a fatal and final mistake. McCarthy called Army officials out in public and private sessions, focusing on a Brigadier General's promotion of a dentist with alleged Communist leanings. The confrontation with the Army culminated in testimony from Joseph Welch, a private attorney hired to represent the Army, who snapped after McCarthy directed one of his famous insinuations directed against another attorney at Welch's firm, with the object of intimidating Welch into acquiescence. Welch fired back, "Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness." In the high-profile hearing, which was broadcast live on national television, Welch defended his colleague:

WELCH: It is, I regret to say, equally true that I fear he shall always bear a scar, needlessly inflicted by you. If it were in my power to forgive you for your reckless cruelty, I would do so. I like to think I'm a gentle man, but your forgiveness will have to come from someone other than me. That earnest question would resonate powerfully with an American public exhausted and disgusted by the Un-American witch hunt. With the utterance of those words, McCarthy's career came to an abrupt end. Humiliated in front of a national audience, McCarthy suddenly discovered that Americans could see through his attack-dog bluster. His ability to shape public opinion destroyed, McCarthy was censured by the Senate for abusing his power. His health began to decline, fueled in no small part by his rampant alcoholism and an addiction to morphine, and he died in disgrace in May 1957. The House Un-American Activities Committee continued for another two decades, although it changed its name to the more politically-correct House Internal Security Committee in 1969. The Government Operations Committee was renamed the Committee on Governmental Affairs in 1978. In recent years, a crop of McCarthy apologists has sprung up, arguing that old Joe really wasn't that bad, and that a lot of the people he hammered were in fact communists. This phenomenon may be connected to the latest iteration of the Un-American craze, Attorney General John Ashcroft's modern crusade against terrorism. While inevitable, the oft-repeated comparisons between McCarthyism and Ashcroftism are doomed to fall flat. As bad as McCarthy's tactics were, remarkably few people ended up in prison because of them. Ashcroft, on the other hand, imprisoned thousands of Arab-Americans after September 11 with no charge and apparently solely on the basis of their ethnicity, with no pesky public hearings and thus no risk that anyone might embarrassingly inquire after his sense of decency. Whew!

|

The foundation of America was actually based on anti-monarchy

views and not anti-Communist views, a fact which may not be

immediately clear to anyone who grew up during the 1950s, or for that

matter, during the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and the first part of the

1990s.

The foundation of America was actually based on anti-monarchy

views and not anti-Communist views, a fact which may not be

immediately clear to anyone who grew up during the 1950s, or for that

matter, during the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and the first part of the

1990s. The House Committee on Un-American Activities was formed in

1938 as a special committee to investigate all kinds of subversives

on U.S. soil, including

The House Committee on Un-American Activities was formed in

1938 as a special committee to investigate all kinds of subversives

on U.S. soil, including  shot back at the committee that was attempting, rather successfully,

to destroy their lives and careers. All ten were convicted of

contempt of Congress, after exercising their right to refuse to

answer HUAC's questions on Fifth Amendment grounds. All ten went to

prison for at least a year. On their release, they found themselves

blacklisted, although some managed to get uncredited work from time

to time.

shot back at the committee that was attempting, rather successfully,

to destroy their lives and careers. All ten were convicted of

contempt of Congress, after exercising their right to refuse to

answer HUAC's questions on Fifth Amendment grounds. All ten went to

prison for at least a year. On their release, they found themselves

blacklisted, although some managed to get uncredited work from time

to time.

In the case of one former employee, "I looked into his record

and I found that, No. 1, that he had no religion and, No. 2, that he

had considerable time at the Moscow Art Theater studying art

direction or something." In the case of another, Disney said,

"If he isn't a communist, he sure should be one." Disney

recommended outlawing labor unions for Un-American tendencies such as

interfering with his profits. The committee tabled the

recommendation.

In the case of one former employee, "I looked into his record

and I found that, No. 1, that he had no religion and, No. 2, that he

had considerable time at the Moscow Art Theater studying art

direction or something." In the case of another, Disney said,

"If he isn't a communist, he sure should be one." Disney

recommended outlawing labor unions for Un-American tendencies such as

interfering with his profits. The committee tabled the

recommendation.

Richard Nixon, then a rookie Congressman from California, trotted

out the "Pumpkin Papers" in a dramatic press conference

which instantly elevated him to national celebrity. Unfortunately,

like many of Nixon's subsequent career highlights, the accomplishment

was quickly tarnished with the taint of scandal and deceit.

Richard Nixon, then a rookie Congressman from California, trotted

out the "Pumpkin Papers" in a dramatic press conference

which instantly elevated him to national celebrity. Unfortunately,

like many of Nixon's subsequent career highlights, the accomplishment

was quickly tarnished with the taint of scandal and deceit.

Hiss escaped an espionage charge by virtue of the statute of

limitations, but he was convicted of perjury related to the papers

and sentenced to five years in jail. He denied all the charges

against him until his dying day. After the collapse of the Soviet

Union, documents were released to the public which apparently

confirmed that Hiss had been a Soviet spy, but the pedigree of the

latest disclosures is considered questionable by some.

Hiss escaped an espionage charge by virtue of the statute of

limitations, but he was convicted of perjury related to the papers

and sentenced to five years in jail. He denied all the charges

against him until his dying day. After the collapse of the Soviet

Union, documents were released to the public which apparently

confirmed that Hiss had been a Soviet spy, but the pedigree of the

latest disclosures is considered questionable by some.

McCarthy repeatedly claimed he had a list of Communists working in

the State Department, but the number of names on his list comically

changed every time he repeated the charge. (The ever-changing figure

was cuttingly satirized in 1962's The Manchurian Candidate when

pompous Senator Johnny Iselin plaintively asks his wife, a Soviet

spy, to give him "Just one real simple number that'd be easy for

me to remember.")

McCarthy repeatedly claimed he had a list of Communists working in

the State Department, but the number of names on his list comically

changed every time he repeated the charge. (The ever-changing figure

was cuttingly satirized in 1962's The Manchurian Candidate when

pompous Senator Johnny Iselin plaintively asks his wife, a Soviet

spy, to give him "Just one real simple number that'd be easy for

me to remember.")

Hoover provided McCarthy with a gold mine of unsubstantiated

allegations to use in his hearings, including documentation of

illegal surveillance camouflaged so that it would not be clear the

FBI was the source. Hoover put the FBI's resources to work keeping

tabs on critics of McCarthy (a big job) and performing background

checks on individuals McCarthy wanted to put the screws to.

Hoover provided McCarthy with a gold mine of unsubstantiated

allegations to use in his hearings, including documentation of

illegal surveillance camouflaged so that it would not be clear the

FBI was the source. Hoover put the FBI's resources to work keeping

tabs on critics of McCarthy (a big job) and performing background

checks on individuals McCarthy wanted to put the screws to.

The GOC's executive sessions, held in secret and classified for

decades after McCarthy's death, were also a useful way of screening

potential witnesses. If witnesses in the closed-door hearings were

not properly intimidated, they never found their way to a public

forum where they might embarrass McCarthy. When the Committee smelled

blood, the witnesses would be dragged out for a public humiliation,

especially if McCarthy could find a way to rephrase their testimony

in a damaging light.

The GOC's executive sessions, held in secret and classified for

decades after McCarthy's death, were also a useful way of screening

potential witnesses. If witnesses in the closed-door hearings were

not properly intimidated, they never found their way to a public

forum where they might embarrass McCarthy. When the Committee smelled

blood, the witnesses would be dragged out for a public humiliation,

especially if McCarthy could find a way to rephrase their testimony

in a damaging light.