|

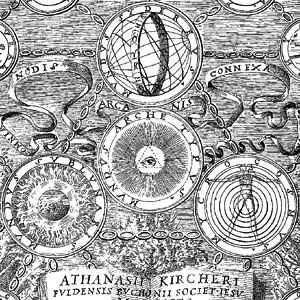

Athanasius Kircher Jesuits have a reputation for representing the intellectual side of Catholicism. That reputation was never more merited than during the life of Athanasius Kircher, a 17th century German scholar who catalogued everything from Egyptian gods to Asian mysticism, in addition to inventing a variety of truly bizarre inventions and creating much of the scientific basis for modern geology.

Jesuits have a reputation for representing the intellectual side of Catholicism. That reputation was never more merited than during the life of Athanasius Kircher, a 17th century German scholar who catalogued everything from Egyptian gods to Asian mysticism, in addition to inventing a variety of truly bizarre inventions and creating much of the scientific basis for modern geology. About the only thing he isn't reknowned for studying is Christianity, making him the consummate Jesuit.

Kircher's prodigious skills as a mathematician and especially as a linguist catapulted him to prominence at an early age. He studied—and in most cases, spoke and wrote—Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, German, French, Spanish, Portuguese, Arabic, Persian, Syrian, Samaritan, Armenian, Coptic and Ethiopian. Kircher spent several years as a conventionally successful teacher and scholar, but in 1628, he began down a path of esotericism that would make him a colorful intellectual celebrity along the lines of Salvador Dali or Andy Warhol, except with more mainstream acceptance.

As later scholars discovered, Kircher's theories were completely wrong in almost every respect (although he did correctly identify the relationship of hieroglyphics to spoken language). It is generally agreed, however, that Kircher was brilliantly wrong, which often works out better than being tediously right.

No matter how right you are, you will eventually be wrong. It happens to all the great minds. The poignant thing about Kircher was that he was so obviously and extraordinarily brilliant and yet so painfully and repeatedly wrong.

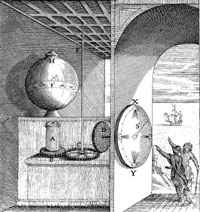

Despite his dalliances in the realms of occult metaphysics and paganism, Kircher was more good to Rome than he was a detriment as he employed his considerable intellect in what would turn out to be a largely hopeless attempt to reconcile the scientific advances of his day with Biblical history. As part of this quest, Kircher traveled to such exotic locations as the smoldering crater of Mount Vesuvius, where he attempted to discern the structure of the world (in order to make it conform to Biblical knowledge). The resulting study, Mundus Subturraneus, was a lavishly illustrated work in the budding scientific field of geology. Once again, Kircher's theories were brilliantly wrong, as he attempted to explain the action of volcanoes and bodies of water through an elaborate system of underground ducts and channels.

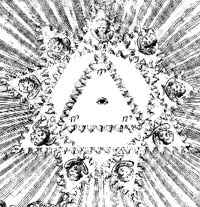

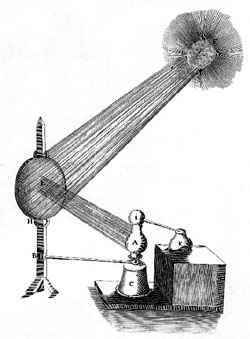

On the other hand, his epic study of magnetism, De Arte Magnetica, was far more colorful than accurate. In the fields of acoustics, optics and magnetism, Kircher was sufficiently adept to invent a series of clever and bizarre devices—from talking statues to magnetic clocks to image projectors—but his conclusions about the underlying theories were (as usual) well-reasoned, imaginative and wrong. Kircher attributed to magnetism everything from God to the movement of planets to the action of tides to sexual attraction.

Arithmologia also attempted to use math to integrate Eastern concepts with European metaphysics. In a separate tome, Kircher created the first scholarly documents outlining Chinese religion and mythology, including elements of Taoism and one of the first Western descriptions of the I-Ching. Again, his scholarly catalog was impressive, but the conclusions he drew from his data were way off base—Kircher claimed that Chinese ideogram writing was a corruption of his beloved hieroglyphic system and that the Chinese (and Mayans and Aztecs for that matter) were all descended from the Egyptians.

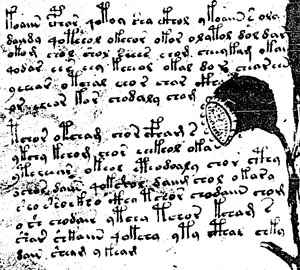

Kircher also invented a "camera obscura" which was remarkably similar in concept and structure to early photographic cameras—except that it was room-sized and didn't use film. Instead, an artist climbed inside the contraption and drew the image as it was projected on a piece of paper. One of his later obsessions was the strange document currently known as the "Voynich Manuscript"—a lengthy catalog of botanical illustrations annotated in a script that remains indecipherable to this day. Buoyed by what he imagined to be his success in solving the hieroglyphic code, Kircher spent the final years of his life on the document, which he possessed until he died.

On his death in 1680 at the age of 79, Kircher's body was buried in Rome, but according to his decidedly odd dying wish, his heart was removed and buried in a shrine he had constructed several miles away. The arrangment was strangely appropriate for a man whose mind had traveled across such wide spaces. In the years after his death, Kircher's reputation began to fall into disrepair as his numerous and often spectacular mistakes were revealed by later scholars. After the initial backlash, however, the staying power of Kircher's vibrant and imaginative ideas and artwork began to redeem his (mostly) forgivable mistakes. Author Umberto Eco was a leading voice in the rehabilitation of Kircher's reputation. The Jesuit is today remembered more for his genius than for his record on accuracy, which is entirely as it should be.

|

Kircher was born in 1601 to a professor of theology and philosophy in a small German town along the Rhone river. Kircher signed up for a tour of duty with the Jesuits when he was 17. He followed his father's academic path, but opted for ordination instead of the secular life after a number of traumatic incidents, culminating in what he believed was a

Kircher was born in 1601 to a professor of theology and philosophy in a small German town along the Rhone river. Kircher signed up for a tour of duty with the Jesuits when he was 17. He followed his father's academic path, but opted for ordination instead of the secular life after a number of traumatic incidents, culminating in what he believed was a  It started with his introduction to hieroglyphics. No one had ever been able to make sense of the ancient symbols, and Kircher studied them at length—an obsession that would last for most of his life. He eventually determined that the ancient Egyptian language was actually spoken by Adam, that Moses was in fact the legendary Egyptian

It started with his introduction to hieroglyphics. No one had ever been able to make sense of the ancient symbols, and Kircher studied them at length—an obsession that would last for most of his life. He eventually determined that the ancient Egyptian language was actually spoken by Adam, that Moses was in fact the legendary Egyptian  "Brilliantly wrong" proved to be a trend in Kircher's life. Ptolemy was wrong when he said the universe revolved around the earth, Copernicus was wrong when he said the universe actually revolved around the sun, Newton was wrong when he said time was absolute and when he dabbled in alchemy,

"Brilliantly wrong" proved to be a trend in Kircher's life. Ptolemy was wrong when he said the universe revolved around the earth, Copernicus was wrong when he said the universe actually revolved around the sun, Newton was wrong when he said time was absolute and when he dabbled in alchemy,  Kircher set about crafting theories and gathering knowledge with a vengeance. Called to Rome by the pope, he quickly became a favorite of the

Kircher set about crafting theories and gathering knowledge with a vengeance. Called to Rome by the pope, he quickly became a favorite of the  Kircher continued to write about his wide variety of interests, producing tome after tome of scientific study, containing error after error, with the occasional gem of correctness scattered amid the glorious dross. During an outbreak of

Kircher continued to write about his wide variety of interests, producing tome after tome of scientific study, containing error after error, with the occasional gem of correctness scattered amid the glorious dross. During an outbreak of  Astronomy, music, archaeology, history... The books kept on coming. Arithmologia was a compendium of magical formulas, arcane symbols,

Astronomy, music, archaeology, history... The books kept on coming. Arithmologia was a compendium of magical formulas, arcane symbols,  Kircher's health began to decline as he entered his late 60s, but he continued to study and publish on a variety of topics. He built a museum featuring his strange and wonderful inventions, including a variety of tricks and illusions including "talking statues" and a fountain in which water seemed to pour upward in defiance of gravity. Among the displays was Kircher's "magic lantern"—which used a lamp, lenses and glass slides to project an image on the wall, foreshadowing the motion picture projector before film had even been conceived of.

Kircher's health began to decline as he entered his late 60s, but he continued to study and publish on a variety of topics. He built a museum featuring his strange and wonderful inventions, including a variety of tricks and illusions including "talking statues" and a fountain in which water seemed to pour upward in defiance of gravity. Among the displays was Kircher's "magic lantern"—which used a lamp, lenses and glass slides to project an image on the wall, foreshadowing the motion picture projector before film had even been conceived of.  Uncharacteristically, he never produced a translation of the manuscript—a testament to its impenetrability, or perhaps the industrious Jesuit was just slowing down in his old age.

Uncharacteristically, he never produced a translation of the manuscript—a testament to its impenetrability, or perhaps the industrious Jesuit was just slowing down in his old age.