|

Leonardo da Vinci Leonardo da Vinci was an amazing guy. But let's get one thing straight: he didn't have a fucking code.

Leonardo da Vinci was an amazing guy. But let's get one thing straight: he didn't have a fucking code.That's no slam on da Vinci, of course. He painted some of the most memorable images in history, including "The Last Supper" and the "Mona Lisa." And his science was as impressive as his art. An engineer and architect, da Vinci invented the helicopter 400 years before there was such a thing as a combustion engine. Many of his inventions are still used today in one form or another, such as the hygrometer, the transmission drive, the ball-bearing axle and the machine gun. But there was no da Vinci code. Sorry. Get over it. Leonardo was born in 1452, near Tuscany in Italy, the bastard son of a local nobleman. He was reportedly an artistic prodigy, who was allowed to pore through his father's library (although he was never recognized as a legitimate offspring). As a child, he was fascinated by art, anatomy and nature. At the tender age of 14, da Vinci traveled to the big city, Florence, where he became an apprentice to a very successful artist of the day named Andrea del Verrocchio, who is best remembered for such classic works as... well, OK, he's best remembered for having Leonardo as an apprentice. The judgments of history are cold and heartless.

Now, you may be thinking that "teenage boy in the big city lives with grown-up artists" sounds a bit fishy, but it was a perfectly acceptable situation within the historical context.

According to legend, Verrocchio swore he would never paint again, so humiliated was he by his student's superior talent. Apparently unaware of the legend, Verrocchio appears to have continued painting after 1477 (or, more accurately, he continued to sign his name on the paintings made by his students), but he did refocus his work on sculpture as the years went on. On the heels of this fabulous (if slightly apocryphal) triumph, da Vinci set out to make his own way in the world. His first major commission was a painting for a nearby monastery. "The Adoration of the Magi" was a sepia-toned panel that was never quite finished but is still considered great. With momentum on his side and the public humiliation of the aforementioned sodomy charge nipping at his heels, da Vinci decided it was time to move on up to Milan, where the local duke offered him a patronage.

On the face of it, "The Last Supper" is just one of about eleventy-zillion painting depicting Jesus Christ and his Apostles enjoying their last big shindig before the centurions arrive for the opening act of the Crucifixion. Admittedly, it's a pretty good version of the tableaux, and it's an unusually big one at 29 feet wide, painted on the wall of a Milanese convent. Leonardo painted "The Last Supper" over the course of three years, working at the behest of his patron, the Duke of Milan. Artistically, "The Last Supper" is exceptional—and for several hundred years, that was all anyone had to say about, except for "It's not holding up very well, is it?" The painting was made using an experimental new technique, which was unfortunately not very durable. Numerous restorations have been attempted over the centuries, with varying degrees of success.

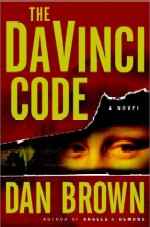

After Leo's death, "The Last Supper" became the object of a bizarre 20th century fetish cult that believes there are secret messages hidden in every square inch of wall. At first the province of obscure scholars and authors, these theories slowly ballooned into the public eye, culminating in the publication of The Da Vinci Code, a 2003 best-seller that lifted elements from a dozen ancient conspiracy theories, including tales of the Knights Templar, the Cathars, and the Holy Grail.

After Leo's death, "The Last Supper" became the object of a bizarre 20th century fetish cult that believes there are secret messages hidden in every square inch of wall. At first the province of obscure scholars and authors, these theories slowly ballooned into the public eye, culminating in the publication of The Da Vinci Code, a 2003 best-seller that lifted elements from a dozen ancient conspiracy theories, including tales of the Knights Templar, the Cathars, and the Holy Grail.

The theory propounded by the book—that Jesus didn't die on the cross, but in fact survived to father a line of French kings—is not terribly outrageous, but it's also not proven. The major plot point of the "code" is based on analysis of the painting's tiniest details, which happen to loom rather large when you view the picture at its original 27-foot width.

While the Jesus bloodline theory is actually pretty interesting, and not completely outside the realm of possibility, the da Vinci part of the premise is the weakest from an educated perspective. Virtually no one with a shred of credibility believes The Last Supper is Leonardo's coded message from beyond the grave about the paternity of Christ. (Then again, during Leonardo's life, virtually no one with a shred of credibility believed the earth was round, either.)

While da Vinci continued to work his artistic magic, Borgia wasn't interested in pretty pictures so much as he was in war and strategy. da Vinci, who had always been a dabbler in science and engineering, was teamed with Niccol Machiavelli, who lived in Florence at the time, to execute an elaborate plan for building a strategic canal system. The plan was a bust, but Macchiavelli and da Vinci remained friends. A highlight of da Vinci's second stint in Florence was a much-anticipated "paint battle" in which da Vinci and Michelangelo were to create murals on facing walls in a city plaza. The battle royale ended in a no-contest. Both artists were notorious for not finishing their works, and they lived up to their respective reputations. During this period, da Vinci finished his other enduring masterpiece, "La Gioconda"—"the joyful one", or as it is known in English, the "Mona Lisa". These days, it's taken as an established fact that the Mona Lisa's expression holds some sort of secret, that she wears an enigmatic smile. This interpretation of the painting, however, is fairly recent, first being made by art historian Walter Pater in 1873. In his book The Rennaisance, Pater wrote the following purple passage on the painting:

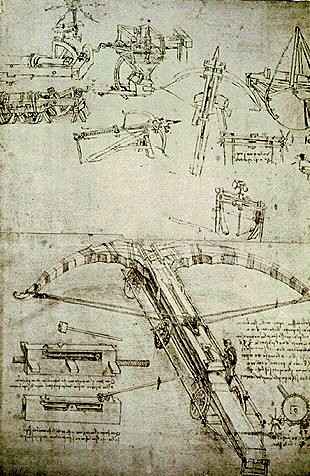

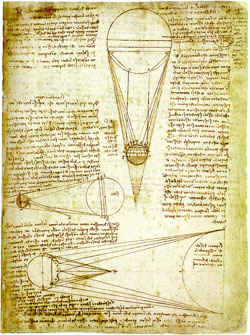

To better inform his studies of bone and musculature, Leonardo dissected several cadavers, a practice that was still quite controversial at the time. However, for the most part, da Vinci avoided the sort of religious and political rows that would plague other scientists of the period, like Galileo. Leonardo's fascination with science led him down many dead-ends, but also to quite a few useful discoveries. da Vinci is credited with a number of inventions that were firsts for his time, including some so far ahead of his time that they wouldn't actually be built for centuries. They include:

In addition to these still-employed devices, da Vinci invented a series of scientific instruments for measuring everything from tensile strength to humidity.

Leonardo collected his technological innovations in notebooks called codeci. One of the best preserved is the Codex Leicester, deals with everything from fossils to astronomy, included sketches of the how the moon's light is seen from earth, and the properties of water and rocks. For many years, the Codex Leicester was owned by Armand Hammer who called it the Codex Hammer from 1980 until his death; in 1994, it was bought by Bill Gates, who returned its original name. da Vinci had become an extremely celebrated artist by the time he entered middle age, and in Italy, there was only one more realm for him to conquer: Rome. In 1513, da Vinci entered the patronage of Pope Leo X, a scion of the wealthy and powerful Medici family. At the Vatican, Leonardo had mixed successes. Artistically, he found himself dominated by his rivals, Michelangelo and Raphael. Although he received several commissions for paintings, he also spent a lot of time on architecture and engineering.

After a couple of years, Leonardo left Rome under the patronage of Giuliano Medici, the Pope's brother, where he appears to have spent the last years of his life quietly. For the last decade of da Vinci's life, his constant companion (and presumed lover) was a much younger man named Francesco Melzi, whose life is mostly distinguished by that relationship. He was reportedly an extremely good looking guy, a minor nobleman from Milan and a talented amateur artist. After Leonardo died, Melzi inherited everything, including the inventions, the codeci, books and numerous drawings and paintings, which he carefully preserved for posterity. Leo was a pretty interesting guy in life, but in death, he took on mythic proportions. For centuries, various untrue legends surrounding his life and his works, including a variety of spurious claims about his death and many forgeries of his work. Among the bullet points you can cross off your list of "things to believe," da Vinci did not die in the arms of the king of France, he didn't invent the bicycle, and he didn't use the same model for Judas as he did for Jesus in "The Last Supper." In the 20th century, Leonardo has been an obsessive figure in the pages of fiction, with appearances in everything from Star Trek to a Saturday morning cartoon of Bill and Ted's Excellent Adventure. One of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles was named after da Vinci. Between fiction and nonfiction, Leonardo has been featured in hundreds of movies and television shows, and tens of thousands of books. And with the breakout success of The da Vinci Code, and a movie adaptation on the way... Well, let's just say it won't be long before you're really fucking sick of Leonardo da Vinci. If you aren't already.

Timeline

|

del Verrocchio had a number of talented students who "assisted" him in painting his most successful works, in the custom of the day. Leonardo spent his days and nights hanging out with Verricchio, his fellow apprentices and other luminaries of the Florence art scene.

del Verrocchio had a number of talented students who "assisted" him in painting his most successful works, in the custom of the day. Leonardo spent his days and nights hanging out with Verricchio, his fellow apprentices and other luminaries of the Florence art scene.  The perfectly acceptable social context didn't stop da Vinci from turning out completely queer, of course. Florence was very much the

The perfectly acceptable social context didn't stop da Vinci from turning out completely queer, of course. Florence was very much the  In 1477, Verrochio made a painting titled "The Baptism of Christ," a project which Leonardo assisted by painting an angel on the far left of the picture. Although it's not immediately apparent to the untrained eye (or even to the trained eye), the angel illustration was so dazzlingly great that it made the rest of the painting look like a piece of total crap.

In 1477, Verrochio made a painting titled "The Baptism of Christ," a project which Leonardo assisted by painting an angel on the far left of the picture. Although it's not immediately apparent to the untrained eye (or even to the trained eye), the angel illustration was so dazzlingly great that it made the rest of the painting look like a piece of total crap.

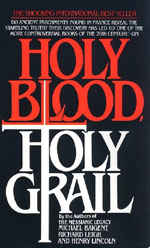

The connection between da Vinci and the Jesus bloodline was first outlined in the book Holy Blood, Holy Grail, whose authors have sued the publisher of The da Vinci Code for plagiarism. According to the authors, Leonardo was the Grand Master of a

The connection between da Vinci and the Jesus bloodline was first outlined in the book Holy Blood, Holy Grail, whose authors have sued the publisher of The da Vinci Code for plagiarism. According to the authors, Leonardo was the Grand Master of a  Anyway, after several successful years in Milan, da Vinci returned in triumph to Florence, where he was hailed as a conquering artistic hero. Leo traded up the Duke of Milan for a new patron,

Anyway, after several successful years in Milan, da Vinci returned in triumph to Florence, where he was hailed as a conquering artistic hero. Leo traded up the Duke of Milan for a new patron,  "La Gioconda" is, in the truest sense, Leonardo's masterpiece. [...] We all know the face and hands of the figure, set in its marble chair, in that circle of fantastic rocks, as in some faint light under sea. [...] The presence that rose thus so strangely beside the waters, is expressive of what in the ways of a thousand years men had come to desire. Hers is the head upon which all "the ends of the world are come," and the eyelids are a little weary. It is a beauty wrought out from within upon the flesh, the deposit, little cell by cell, of strange thoughts and fantastic reveries and exquisite passions. Set it for a moment beside one of those white Greek goddesses or beautiful women of antiquity, and how would they be troubled by this beauty, into which the soul with all its maladies has passed! All the thoughts and experience of the world have etched and moulded there, in that which they have of power to refine and make expressive the outward form, the animalism of Greece, the lust of Rome, the mysticism of the middle age with its spiritual ambition and imaginative loves, the return of the Pagan world, the sins of the Borgias. She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in deep seas, and keeps their fallen day about her; and trafficked for strange webs with Eastern merchants; and, as Leda, was the mother of Helen of Troy, and, as Saint Anne, the mother of Mary; and all this has been to her but as the sound of lyres and flutes, and lives only in the delicacy with which it has moulded the changing lineaments, and tinged the eyelids and the hands.

"La Gioconda" is, in the truest sense, Leonardo's masterpiece. [...] We all know the face and hands of the figure, set in its marble chair, in that circle of fantastic rocks, as in some faint light under sea. [...] The presence that rose thus so strangely beside the waters, is expressive of what in the ways of a thousand years men had come to desire. Hers is the head upon which all "the ends of the world are come," and the eyelids are a little weary. It is a beauty wrought out from within upon the flesh, the deposit, little cell by cell, of strange thoughts and fantastic reveries and exquisite passions. Set it for a moment beside one of those white Greek goddesses or beautiful women of antiquity, and how would they be troubled by this beauty, into which the soul with all its maladies has passed! All the thoughts and experience of the world have etched and moulded there, in that which they have of power to refine and make expressive the outward form, the animalism of Greece, the lust of Rome, the mysticism of the middle age with its spiritual ambition and imaginative loves, the return of the Pagan world, the sins of the Borgias. She is older than the rocks among which she sits; like the vampire, she has been dead many times, and learned the secrets of the grave; and has been a diver in deep seas, and keeps their fallen day about her; and trafficked for strange webs with Eastern merchants; and, as Leda, was the mother of Helen of Troy, and, as Saint Anne, the mother of Mary; and all this has been to her but as the sound of lyres and flutes, and lives only in the delicacy with which it has moulded the changing lineaments, and tinged the eyelids and the hands.

As the 15th century gave way to the 16th, da Vinci found himself increasingly interested in science, to the detriment of his painting career. While he still sketched and took commissions, Leo began to focus on such disciplines as mathematics, architecture, engineering, geology, botany, hydraulics and anatomy. da Vinci's anatomical sketches are still studied today.

As the 15th century gave way to the 16th, da Vinci found himself increasingly interested in science, to the detriment of his painting career. While he still sketched and took commissions, Leo began to focus on such disciplines as mathematics, architecture, engineering, geology, botany, hydraulics and anatomy. da Vinci's anatomical sketches are still studied today.  At least as impressive as the inventions that worked were the inventions that didn't work. Although he lacked several key components and raw materials, da Vinci nevertheless envisioned a series of inventions that would eventually be used in the modern world, sometimes with only minor changes to his original designs, including the helicopter, the hang-glider and the machine gun.

At least as impressive as the inventions that worked were the inventions that didn't work. Although he lacked several key components and raw materials, da Vinci nevertheless envisioned a series of inventions that would eventually be used in the modern world, sometimes with only minor changes to his original designs, including the helicopter, the hang-glider and the machine gun.  One of the few paintings he completed in this period was "St. John the Baptist," another controversial work which has been the subject of much discussion over the years. Catty observers often cite the painting as one indication of Leonardo's gayness, which isn't really so controversial that it needs to be continually re-proven. In the work, John appears to be sexually ambiguous, soft and feminine, with a decidedly "come hither" expression.

One of the few paintings he completed in this period was "St. John the Baptist," another controversial work which has been the subject of much discussion over the years. Catty observers often cite the painting as one indication of Leonardo's gayness, which isn't really so controversial that it needs to be continually re-proven. In the work, John appears to be sexually ambiguous, soft and feminine, with a decidedly "come hither" expression.