|

Catholicismaka the Holy Roman Catholic Church See also Popes, Gnosticism, Inquisition, Heresy, Crusades, Jesus Christ, The Historical Construction of The Bible, Secret Archives of the Vatican, Marian Apparitions, Relics

See also Popes, Gnosticism, Inquisition, Heresy, Crusades, Jesus Christ, The Historical Construction of The Bible, Secret Archives of the Vatican, Marian Apparitions, RelicsThe Roman Catholic Church claims to be the official keeper of the teachings and traditions of Jesus Christ. This in itself is not surprising. Virtually every religion claims it has exclusive access to the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. What's really impressive is the massively complicated structure of beliefs piled on top of this simple claim, many of which have next to nothing to do with anything Jesus taught. Catholics believe their religion is directly descended from Christ, via St. Peter, the apostle Jesus allegedly called "the rock (on which) I shall build my church." Early Christianity was a mishmash of different beliefs, espoused by various charismatic figures. Although records are sparse, we know the names of a few influential early Christian teachers including the apostles Peter, Paul and James, and other figures who were later dismissed as heretics, including gospel writers using the names of the Apostle Thomas and Jesus's pal Mary Magdalene. From what little evidence survives, we can infer that there were several distinctly different sects of Christianity during the first decades after Christ's death. The two most powerful, as best anyone can determine, were the Jerusalem Church and the Roman Church. After the death of Christ, the 11 surviving apostles had set up shop in Jerusalem, an entirely natural home base for what was an essentially Jewish sect. The Jerusalem church was led by James, sometimes described as the brother of Jesus, and to some extent by Peter. But Christianity quickly spread beyond the confines of Judaism, in large part because of Paul, a Jew and a Roman citizen who had converted to Christianity after Christ's death. Paul (who never heard Jesus preach in life) made significant changes and additions to the teachings of Jesus to make them more palatable to non-Jewish audiences. He successfully converted many Romans to his version of Christianity, which eventually became the dominant strain. Paul had to write many letters to the early Christians in order to make sure they kept to his vision. Peter and Paul eventually traveled to Rome, where an underground church had established itself. Both were martyred during the mid 60s C.E. At some point in all this, the official story goes, Peter formally became leader of the church. Before his death, Peter allegedly passed the torch to Linus, who is believed to be the second pope despite a dearth of historical documentation. James and the Jerusalem Church saw their influence dwindle in the decades that followed Christ's death. When Peter left for Rome, it reflected a power shift that had already been underway for some time. The final blow came when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in 70 C.E. The carnage scattered the Jewish Christians and removed their power base. In the ensuing void, Paul's Gentile converts easily took control. Bust even among Paul's followers, the first several decades of Christianity were fractious and inconsistent. Making religion is like making sausage; you're probably happier not knowing. The early church was a haphazard collection of disparate sects with often wildly divergent beliefs that all centered around the figure of Jesus to a greater or lesser extent. Early Christian theologians desperately tried to create a single orthodox base for Christianity, but none of these efforts succeeded until the fourth century.

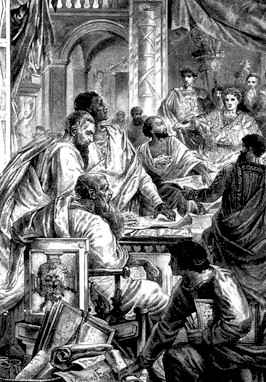

Constantine was motivated by a desire for political stability. He was not a Christian and wasn't baptized until he lay on his deathbed. Nevertheless, he was a force to be reckoned with. Although he didn't directly shape the theological content of Christianity, Constantine convened the Council of Nicea in 325, bringing together the scattered bishops of Christian communities around the ancient world. Basically, he locked them in a room and told them not to come out until they had agreed on a definition for orthodox Christianity. The resulting "Nicene Creed" defines Roman Catholicism today. Everything else was designated as heresy and targeted for extermination.

The Beliefs of the Catholic ChurchDrafted at the first synod and formally ratified toward the end of the 4th century, the Nicene creed outlines the basic beliefs of the Roman Catholic faith and has been recited with minor variations by believers ever since:

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten Son of God, and born of the Father before all ages, light of light, true God of true God. Begotten not made, consubstantial to the Father, by whom all things were made. Who for us men and for our salvation came down from heaven. And was incarnate of the Holy Ghost and of the Virgin Mary and was made man; was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate, suffered and was buried; and the third day rose again according to the Scriptures. And ascended into heaven, sits at the right hand of the Father, and shall come again with glory to judge the living and the dead, of whose Kingdom there shall be no end. And in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of life, who proceeds from the Father, who together with the Father and the Son is to be adored and glorified, who spoke by the Prophets. And one holy, catholic, and apostolic Church. We confess one baptism for the remission of sins. And we look for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. Amen. The creed unified various strains of thought about Jesus and his teachings, including a few items that were nowhere to be found in the four gospels which were finally identified as "canonical."

Over the centuries, other important doctrinal points arose. Many of these concepts dated back to the first century in some form or another, but most of them were not fully fleshed out by the time of the Nicene Council. The most important of these include:

In addition to these main points, there are a host of beliefs which are today considered uniquely Catholic, including a prohibition on women as priests and an insistence that priests may not marry. These precepts were not necessarily part of Christian practice in the first century after Christ.

Other major Catholic beliefs include:

The PapacyThe one point that irrevocably sets the Catholic Church apart from all other versions of Christianity is the issue of the papacy. Catholics believe that the pope is the direct successor to Peter, a concept known as the apostolic succession, which invests the papacy with a mandate to lead Catholicism which supposedly dates back to Jesus himself.

The need for such a limitation became clear pretty early in Church history. By the close of Christianity's first millennium, the papacy had been occupied by some truly mindblowing hedonists and degenerates. The phrase "died while committing adultery" appears surprisingly often when you review the annals of the Vatican. The list of popes includes such distinguished figures as John XII, who had sex with his mother and sisters; John VIII, who may have been a female transvestite masquerading as a man; Clement V, who unleashed the terrors of the Inquisition against the Knights Templar in a naked grab for the society's valuable real estate; and Sergius III, who reportedly fathered an illegitimate child through incest and then installed that child as Pope John XI. Many non-Catholics have trouble understanding how this extremely uneven track record can possibly reflect the divine mandate implied by the doctrine of the apostolic succession. The confusion deepens when you see just how spotty the actual succession can be. For the first 100 years after the birth of Christ, there exists only a bare approximation of a historical record to vindicate the notion that the papacy goes all the way back to Peter. If you can get past that rather significant point, you then find that there is no particular indication that the early Christians gave any special or universal rank to the pope, who was then known simply as the bishop of Rome. The most powerful early Christian bishoprics included Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Constantinople, but many other bishops were well-represented and politically powerful.

Then there's the "unbroken succession" issue. For most of the Catholic Church's history, the selection of popes has been a haphazard affair. Sometimes popes were elected, at other times they were appointed. Some popes chose their own successors. On several occasions, popes were installed or deposed by the military might of Roman emperors and Italian kings. Sometimes there were two claimants to the papacy at once, or even three. Such "antipopes" began to appear with alarming regularity as early as the third century of the Church. There were at least 30 before the election of popes was standardized in the 16th century. The leading status of the Bishop of Rome was, at first, a secular political consideration. Rome was the heart of the Roman Empire, which became Christian in the wake of Constantine I. Naturally, the Bishop of Rome was in a position to represent himself effectively. Up until the fourth century, the word "pope" wasn't even specific to Rome and applied to any bishop. Etymologically speaking, the beginning of the papacy can be traced to Pope Siricus the 38th bishop of Rome installed at the end of the fourth century, according to the list used by the church, who ruled on various doctrinal matters as if his opinion was the one that mattered. The actual stated doctrine of infallibility evolved slowly over the centuries that followed, but it wasn't precisely codified until the end of the 19th century. The nature of the papacy has also varied wildly throughout the years. From the eighth century through medieval times, popes frequently took an active role in global politics, even going so far as to launch wars from time to time. In contrast, the 21st century papacy is politically impotent, ruling a few square miles of Vatican City.

The Future of the Catholic ChurchThe Catholic Church is still the largest single denomination in the world, with more than a billion believers who identify themselves as members. But time has wrought ravages on Rome's status, power and future outlook.Although the entire history of Christianity is rife with schisms, heresies and breakaways, the watershed moment for Catholicism came with the Protestant Reformation, the first Christian movement to successfully break with Rome (without being exterminated) since Constantine originally consolidated the Church in Nicea. Every year, there are fewer and fewer Catholics, as a percentage of the world's population. The fastest growing religion in the world, Sunni Islam has close to a billion adherents and will almost certainly surpass Catholicism within the next several years.

Few young Catholics are inspired to take up the priesthood these days. One study suggests that by 2020, about half of all priests will be older than 70, and that survey was conducted before the American church was rocked by reports that dozens of priests had been molesting young boys for decades while church authorities covered up their offenses. Over the long history of the church, there have occasionally been a few who prophesied its end. None of these prophecies speak of death by attrition. Religions are not expected to go out with a whimper; true believers demand a bang. But if Armageddon is on the wing, it's hard to see how the Catholic Church ends up being the major player. Granted, the world is currently consumed with a Holy War, and there are plenty of people who are happy to cast Osama bin Laden in the role of Antichrist. But Pope John Paul II wasn't exactly a robust leader likely to call Catholic troops to the final war. His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, had just turned 78 years young when he was made Pope on 18 April 2005, and openly admits his tenure will be short-lived (literally). Not very encouraging. According to a Catholic church legend, St. Malachy presented Pope Innocent II with a list of all the future popes, in what was said to be a divinely inspired prophecy. There are 13 popes remaining on the list, now that J.P. II had made his final farewell. According to the final prophecy of St. Malachy:

In the final persecution of the Holy Roman Church there will reign Peter the Roman, who will feed his flock amid many tribulations, after which the seven-hilled city will be destroyed and the dreadful Judge will judge the people. The End.No pope has ever taken the name Peter, and it's hard to imagine anyone would, after a prophecy like that. Of course, Peter could be the future pope's birth name, or it could be one of those tricky metaphorical deals to which prophets are so often prone. Papal reigns have ranged from days to decades, so 13 popes is a pretty indefinite amount of time. On the bright side, it leaves open the possibility that a bang might break out before the inevitable triumph of the whimper. Check back with us in 80 years or so for an update.

|

Christianity had been outlawed in the Roman Empire for its entire history. Then, in 313 C.E., a woman named Helena converted to Christianity. Helena just happened to be the mother of Roman Emperor Constantine, and she prevailed on him to legalize the religion. Constantine did her one better, not only legitimizing Christianity for the first time but exerting his political might to force the divergent Christian sects into an uneasy unity.

Christianity had been outlawed in the Roman Empire for its entire history. Then, in 313 C.E., a woman named Helena converted to Christianity. Helena just happened to be the mother of Roman Emperor Constantine, and she prevailed on him to legalize the religion. Constantine did her one better, not only legitimizing Christianity for the first time but exerting his political might to force the divergent Christian sects into an uneasy unity.  The final Nicene draft included the relatively new concept of the Holy Trinity the idea that God is actually made up of three separate but equal branches as well as the Virgin Birth, the Holy Spirit and the Resurrection of the Dead.

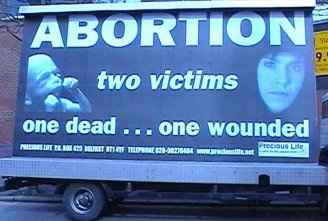

The final Nicene draft included the relatively new concept of the Holy Trinity the idea that God is actually made up of three separate but equal branches as well as the Virgin Birth, the Holy Spirit and the Resurrection of the Dead.  Even more recently, the Catholic Church has chosen to identify itself powerfully with doctrines that are even more recent in derivation, particularly a total ban on contraception and the idea that life begins at the moment of conception (thus making

Even more recently, the Catholic Church has chosen to identify itself powerfully with doctrines that are even more recent in derivation, particularly a total ban on contraception and the idea that life begins at the moment of conception (thus making  In its modern form, the most meaningful part of this mandate is known as infallibility. The doctrine of papal infallibility teaches that the pope is incapable of making an error when it comes to matters of religious teaching. In recent years, this concept has been sharply limited in its application and includes only specific kinds of papal proclamations.

In its modern form, the most meaningful part of this mandate is known as infallibility. The doctrine of papal infallibility teaches that the pope is incapable of making an error when it comes to matters of religious teaching. In recent years, this concept has been sharply limited in its application and includes only specific kinds of papal proclamations.  When Constantine wanted to unify the church, he didn't rely on Sylvester, the Bishop of Rome at that time. He called in all 250-plus bishops from around Christendom, all of whom had their own special ideas of what constituted a Church. Pope Sylvester I was barely a footnote to the proceedings.

When Constantine wanted to unify the church, he didn't rely on Sylvester, the Bishop of Rome at that time. He called in all 250-plus bishops from around Christendom, all of whom had their own special ideas of what constituted a Church. Pope Sylvester I was barely a footnote to the proceedings.  Even more foreboding, the numbers game here doesn't reflect the depth of involvement with the Catholic Church and its core issues. For most of the billion people who self-identify as Muslims, religion is an overpowering consideration in every aspect of their daily lives. Those who identify themselves as Catholics don't necessarily share that sense of urgency, especially American Catholics, who are notorious for missing Sunday mass and for disagreeing with some of the pope's quaint but still infallible notions about birth control.

Even more foreboding, the numbers game here doesn't reflect the depth of involvement with the Catholic Church and its core issues. For most of the billion people who self-identify as Muslims, religion is an overpowering consideration in every aspect of their daily lives. Those who identify themselves as Catholics don't necessarily share that sense of urgency, especially American Catholics, who are notorious for missing Sunday mass and for disagreeing with some of the pope's quaint but still infallible notions about birth control.