|

Supervolcanoes Supervolcanoes might sound like a sweeps week special on the National Geographic channel, but let's face it—who cares, right? Geological oddity, power and grandeur of nature, tectonic plates, the final and total extinction of humanity, pyroclastic discharge, climate change, blah blah blah, same old...

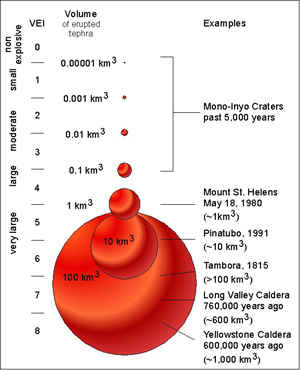

Supervolcanoes might sound like a sweeps week special on the National Geographic channel, but let's face it—who cares, right? Geological oddity, power and grandeur of nature, tectonic plates, the final and total extinction of humanity, pyroclastic discharge, climate change, blah blah blah, same old...Except that cute little geyser in Yellowstone Park—the one your parents dragged you to see when you were eight—is actually a ticking volcanic time bomb capable of covering the whole continent of North America under several inches of ash, while simultaneously shrouding the entire earth in a choking haze of burning airborne ash and smoke. The rains, when they come, will be black and filthy—and so too, eventually, the fresh groundwater we drink. The Earth's average temperature will drop anywhere from two to 50 degrees. The supervolcano at Yellowstone (just one of several around the world) detonates with the same regularity as the cute little geyser—except the volcano only goes off once every 600,000 years. The last time it blew up was 640,000 years ago. We are officially living on borrowed time. There is no hard and fast rule about what makes one volcano "super" as opposed to "very impressive." The volcano at Krakatoa has erupted with supervolcano force during prehistory. Its more recent eruptions (in the sixth and 19th centuries) had global ramifications, but they weren't quite "super." A supervolcano eruption could be hundreds of times the size of the Krakatoa eruption around 535 A.D. That eruption cooled the earth by several degrees for several years and may have blotted out the sun for an entire growing season. When you calculate the factors, total human extinction is not too extreme as a possible outcome. There are potential supervolcanoes lurking all over the world, including in North America, South America, and all across the Pacific Ocean. The most recent super-eruption was about 74,000 years ago in Sumatra. It ejected 1,700 cubic miles of ash—enough to cover the entire surface of the earth about half an inch deep. The plume rose into the stratosphere, blotted out the sun and may have cooled global temperatures by as much as 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

There are three notable things about this description. First, it comes from the BBC and not Pat Robertson's Final Days Club. Second, the boldface is theirs, not ours. And third, it describes a blast of a thousand Hiroshima bombs per second lasting for DAYS. Sadly, this supervolcano eruption is not a question of "if" but "when." It is inevitable, the only uncertainties are "How long until it happens?" and "How bad will it be when it does?"

While world leaders and Hollywood filmmakers have entertained themselves devising strategies for avoiding a major asteroid impact, there is no currently imaginable strategy for defusing a supervolcano—if anyone even sees it coming.

An eruption of this magnitude clearly holds severe implications for the survival of species—including homo sapiens (the only one we really care about when push comes to shove). A supervolcano eruption consistent with those from the past would probably not result in the total extermination of humanity, but it could very realistically thin the ranks by somewhere between a few and several billion people. A global temperature drop of 40 degrees—even for a single year—could devastate agriculture and the world food supply. (Soylent Green, anyone?) For instance, if the Yellowstone supervolcano finally meets its missed deadline, it could wipe out the U.S. agricultural belt and likely end America's superpower status. With most of North America a smoldering ruin buried under feet of ash, the future of civilization would most likely rest in the hands of Osama bin Laden. Unpleasant as that prospect might be, the scenario described above isn't even the alarmist perspective. Terrifyingly, it's the conservative estimate of what could happen. A sufficiently large eruption might cause the earth to tilt on its axis of rotation. Although this is unlikely, the results would be pretty spectacular. Assuming the planet wouldn't just fall entirely to pieces, the oceans would slosh over most inhabited land. Although major cities probably wouldn't be completely submerged for more than a few days, even world class divers can only hold their breath for 10 minutes.

Even if the apocalyptists are wrong and the earth's axis remains largely untilted after Yellowstone (or some other supervolcano) finally blows, there is the problem of climate change. In the past, supervolcanoes As noted above, the Toba supervolcano probably cooled the earth by 40 degrees. A 60-degree drop in global temperatures would freeze most of the planet for most of the year, possibly inaugurating a new Ice Age. Since the planet hasn't been frozen in recent memory, no one knows how long it might take to thaw, assuming it eventually does. However, we can look to history for a guide. The last ice age occurred shortly after the Toba eruption. It lasted for about 1,000 years. According to a cheering theory based on DNA evidence (promulgated by Prof. Stanley Ambrose of the University of Illinois), the Toba explosion may have reduced the earth's human population to as few as 5,000 people. Remember how upset we all were on September 11, when we thought as many as 5,000 or 10,000 people working in the World Trade Center might have been killed? Imagine a world where that many people are all that remains. Maybe if you're lucky, the flu pandemic will get you first.

|

The BBC recently estimated the force of a possible Yellowstone eruption in the following colorful terms: "It will explode again with the unimaginable force of a thousand Hiroshima bombs per second... And the eruption will last for days."

The BBC recently estimated the force of a possible Yellowstone eruption in the following colorful terms: "It will explode again with the unimaginable force of a thousand Hiroshima bombs per second... And the eruption will last for days."

have frozen out the planet by throwing so much ash, rock and volcanic glass (collectively known as "tephra") into the atmosphere that it literally blotted out the sun.

have frozen out the planet by throwing so much ash, rock and volcanic glass (collectively known as "tephra") into the atmosphere that it literally blotted out the sun.