rotten > Library > History > Flu Pandemic of 1918

Flu Pandemic of 1918

aka La Grippe, Influenza A

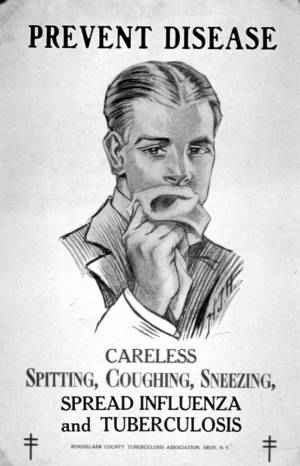

When you think of the great killer plagues of history, a few names come to mind—bubonic plague, tuberculosis, smallpox... You probably don't immediately think of the cold and flu season. But you should.

In 1918 and 1919, the Spanish Flu pandemic killed more people than Hitler, nuclear weapons and all the terrorists of history combined. (A pandemic is an epidemic that breaks out on a global scale.) Spanish influenza was a more severe version of your typical flu, with the usual sore throat, headaches and fever.

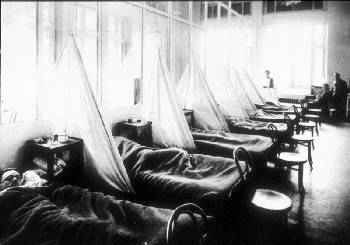

However, in many patients, the disease quickly progressed to something much worse than the sniffles. Extreme chills and fatigue were often accompanied by fluid in the lungs. One doctor treating the infected described a grim scene: "The faces wear a bluish cast; a cough brings up the blood-stained sputum. In the morning, the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cordwood."

If the flu passed the stage of being a minor inconvenience, the patient was usually doomed. There is no cure for the influenza virus, even today. All doctors could do was try to make the patients comfortable, which was a good trick since their lungs filled with fluid and they were wracked with unbearable coughing. The "bluish cast" of victims' faces eventually turned brown or purple and their feet turned black. The lucky ones simply drowned in their own lungs. The unlucky ones developed bacterial pneumonia as an agonizing secondary infection. Since antibiotics hadn't been invented yet, this too was essentially untreatable.

The pandemic came and went like a flash. Between the speed of the outbreak and military censorship of the news during World War I, hardly anyone in the United States knew that a quarter of the nation's population—and a billion people worldwide—had been infected with the deadly disease. More than half a million died in the U.S. alone; worldwide, the estimates ran as high as 50 million.

The pandemic came and went like a flash. Between the speed of the outbreak and military censorship of the news during World War I, hardly anyone in the United States knew that a quarter of the nation's population—and a billion people worldwide—had been infected with the deadly disease. More than half a million died in the U.S. alone; worldwide, the estimates ran as high as 50 million.

There were minor outbreaks around the world throughout 1918, but the real fun didn't start until winter, when the disease broke out in force in Europe, then spread over large segments of the population in America, Europe and Africa. Media censorship kept the story out of the headlines in most countries. Spain foolishly allowed its newspapers to report on the news and paid the price—the pandemic would be known forever as "Spanish Flu."

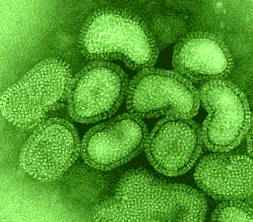

The deadly variant of influenza—technically designated A/H1N1, or simply Influenza A—had cropped up from time to time in history, but the 20th century was an era of global transportation unlike any before it. Automobiles, steamboats and even early air transportation made it easy for infected people to carry the ultra-contagious airborne virus into densely populated cities and commercial ports.

The deadly variant of influenza—technically designated A/H1N1, or simply Influenza A—had cropped up from time to time in history, but the 20th century was an era of global transportation unlike any before it. Automobiles, steamboats and even early air transportation made it easy for infected people to carry the ultra-contagious airborne virus into densely populated cities and commercial ports.

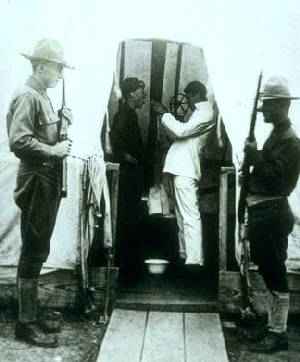

Military personnel provided one important vector for the virus, especially in the U.S., where returning World War I soldiers were among the hardest hit. Half of all U.S. military casualties in Europe died from influenza, not in combat.

Military personnel provided one important vector for the virus, especially in the U.S., where returning World War I soldiers were among the hardest hit. Half of all U.S. military casualties in Europe died from influenza, not in combat.

Because of the media blackout, it's difficult to be sure where the first significant outbreak took place. In March 1918, several hundred soldiers fell ill at Fort Riley, Kansas. Fewer that 50 died, but the company—numbering in the tens of thousands—was deployed to Europe, and apparently they took the flu along with them.

The soldiers, presumably healthier than the average schmoe, were able to survive the illness better than the people to whom they transmitted it. The flu was particularly deadly for people aged 20 to 40—a variation on the usual pattern, which is usually lethal only for the very young and the very old. No one knows exactly why young people in the prime of their life were so susceptible to the disease, but you can't argue with a massive pile of corpses.

And the pile was historic in its proportions. The exact number is unknown, in part due to the fact that many cases of flu were misdiagnosed as pneumonia. In Europe, influenza raced through the population, then expanded into Africa, India and the Middle East with similar speed. Millions of Spaniards were infected, and unknown millions more around the Continent.

And the pile was historic in its proportions. The exact number is unknown, in part due to the fact that many cases of flu were misdiagnosed as pneumonia. In Europe, influenza raced through the population, then expanded into Africa, India and the Middle East with similar speed. Millions of Spaniards were infected, and unknown millions more around the Continent.

Then the U.S. Army brought the virus back to the states, where it afflicted millions more. More than 200,000 Americans died in one month. Because of the war and the pandemic combined, the medical establishment was stretched to its absolute limit, resulting in even more deaths.

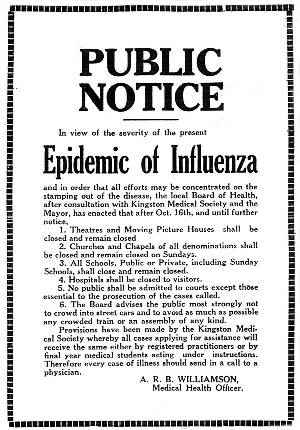

U.S. authorities responded by shutting down public places where the flu might spread, including churches, bars, theaters and schools. Survivors were often reduced to skeletal shadows. Corpses were everywhere. In Philadelphia, they were piled three deep in the streets at times, where they rotted in the open air, provoking a secondary wave of illnesses. In Alaska, many were buried in mass graves under the tundra. In France, bulldozers were used to excavate massive ditches where the dead were unceremoniously thrown. In Ireland, orderlies dug pits behind hospitals to hold the remains of their former patients.

By the end of the second wave, from late summer to early winter 1918, worldwide casualties reached the tens of millions. A third wave in the spring of 1919 concluded the pandemic, for a final minimum estimated death toll between 20 and 30 million people. Most historians believe that the total was closer to 50 million dead --- all in the course of a single year, and medical researchers have recently upped the top range of that estimate to 100 million.

Even with the low end estimates, the Spanish Flu was the most lethal documented pandemic in history—far worse than the more notorious Black Death that ravaged Europe in the Middle Ages.

Even with the low end estimates, the Spanish Flu was the most lethal documented pandemic in history—far worse than the more notorious Black Death that ravaged Europe in the Middle Ages.

No one knows exactly where the killer strain originated. At the time, conspiracy theories were common. Many Americans thought the disease was a German plot, spread through Bayer aspirin. Later, some would suggest that flu vaccinations had actually caused the disease. None of these contentions ever came to more than rank speculation.

Many flu viruses originate in birds. Genetically, bird flus tend to be different from human diseases and are not directly transmittable to humans. However, pigs are susceptible to both human viruses and viruses carried by birds like chickens and ducks. When the virus jumps to a pig, it can mix up with human viruses and mutate while under attack from the pig's immune system. Occasionally, the result is a lethal virus capable of killing people.

Some theories say the "Spanish" flu started in Tibet and spread to Europe, where it was contracted by American troops and brought back to the States. During the 1990s, research suggested that the Spanish flu virus first mutated in American swine. Under this theory, it was contracted by U.S. troops, who carried the virus around the globe during their World War I adventures.

Within the last year, an even more alarming theory has emerged. Scientists studying the genetic structure of the Spanish Flu determined that the avian version was virtually identical to the human version, raising the possibility that the virus jumped directly from birds to people.

Since birds migrate from continent to continent, the ramifications of this theory are huge, suggesting that virus outbreaks could occur almost simultaneously all over the world. With no single point of origin, there isn't much anyone can do to contain such a pandemic.

Whether or not the virus can be transmitted directly from bird to human, there is still a tremendous risk that the Spanish flu—or one of its close genetic cousins—could re-emerge in spectacular fashion.

Whether or not the virus can be transmitted directly from bird to human, there is still a tremendous risk that the Spanish flu—or one of its close genetic cousins—could re-emerge in spectacular fashion.

Modern medicine still can't cure the influenza virus, although it can treat the symptoms and often preserve life in cases that would have defeated the medical establishment of 1918. Flu vaccinations may or may not be effective against the Spanish flu variant. The merits of flu vaccinations are not universally agreed on, and not everyone gets them. Even in the best case scenario for a vaccination program, a mutated flu virus can defeat the protection of a vaccine.

There are other complications as well. Population density is much higher today than it was in 1918, especially in areas where vaccinations are not routine, and overall world population has more than tripled. In addition to those trends, the profile of international travel has changed dramatically since 1918. Tens of billions of people travel far enough to fly each each year, and many more travel more than 50 miles on any given day.

There are other complications as well. Population density is much higher today than it was in 1918, especially in areas where vaccinations are not routine, and overall world population has more than tripled. In addition to those trends, the profile of international travel has changed dramatically since 1918. Tens of billions of people travel far enough to fly each each year, and many more travel more than 50 miles on any given day.

Perhaps the more things change, the more they stay the same. Balancing increased travel against improved health care, the World Health Organization estimates that the next global influenza pandemic could cause 50 million deaths or more, if the strain is as virulent as the Spanish Flu.

Scientists say those millions could be saved by a concerted, lightning fast global effort to quarantine affected areas and aggressively treat the afflicted there. Scientists also say that such an effort ain't gonna happen, because of the recurring motif of the 21st century—"We'll burn that bridge when we come to it."

After all, in 2005, the U.S. couldn't coordinate its response to a hurricane it saw coming for days... and everyone involved in that effort spoke the same language, worked for the same government, followed the same rules and had the benefit of instant coverage by the news media. If influenza broke out in some politically inconvenient place, like China or Darfur, the chances of a coordinated global response are less than zero.

After all, in 2005, the U.S. couldn't coordinate its response to a hurricane it saw coming for days... and everyone involved in that effort spoke the same language, worked for the same government, followed the same rules and had the benefit of instant coverage by the news media. If influenza broke out in some politically inconvenient place, like China or Darfur, the chances of a coordinated global response are less than zero.

In 2005, an article in the New England Journal of Medicine estimated that a recurrence of the 1918 influenza epidemic could kill between 180 million and 360 million people worldwide. The author concluded:

Is there anything we can do to avoid this course? The answer is a qualified yes that depends on how everyone, from world leaders to local elected officials, decides to respond. We need bold and timely leadership at the highest levels of the governments in the developed world; these governments must recognize the economic, security, and health threats posed by the next influenza pandemic and invest accordingly. The resources needed must be considered in the light of the eventual costs of failing to invest in such an effort. The loss of human life even in a mild pandemic will be devastating, and the cost of a world economy in shambles for several years can only be imagined.

All it takes is bold and timely leadership? What a relief!

Pornopolis |

Rotten |

Faces of Death |

Famous Nudes

|