|

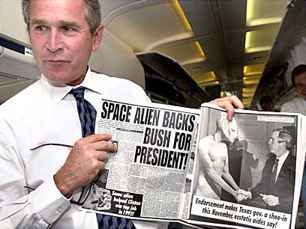

George W. Bush In the past, many of his detractors have dismissed him as a "lightweight." A chump. A joke. Many of them still do. And it's easy to see where they got this impression. Whenever he gives a speech, he invariably comes off sounding like some kind of ignoramus, who experiences difficulty wrapping his lips around the words that scroll across the Teleprompter. And when he has to work off-the-cuff, his folksy demeanor makes him seem more like the store manager of a Radio Shack than the President of the United States.

In the past, many of his detractors have dismissed him as a "lightweight." A chump. A joke. Many of them still do. And it's easy to see where they got this impression. Whenever he gives a speech, he invariably comes off sounding like some kind of ignoramus, who experiences difficulty wrapping his lips around the words that scroll across the Teleprompter. And when he has to work off-the-cuff, his folksy demeanor makes him seem more like the store manager of a Radio Shack than the President of the United States.

But George W. Bush is fully aware of how his enemies perceive him, and this is precisely how he wants them to react. His personality and mannerisms are actually the result of deliberate effort. This is not to say that it's all an act, but he does emphasize these elements of his personality for the benefit of the press and general public. And yet these affectations continue to be astonishingly effective; his act still manages to fool even his political opponents, who really ought to know better. After all, the basis of Bush's phenomenal political career has been people's underestimating him. As his political advisor Karl Rove said in 2002: "I can't explain why they underestimate him, but they do. Whatever the reason, I hope they keep doing it." Dubya has managed to cultivate the look and feel of a down-home good ol' boy. He acts like your wisecracking neighbor or maybe brother-in-law. This is no small accomplishment for someone who grew up with every possible advantage: born into a family of immense wealth and political influence, attended a prestigious prep school, then Harvard and Yale. George became a millionaire in his own right at a very early age; while he was playing in Little League, the boy personally owned a million shares of his father's oil company. And yet, implausible as it may sound for someone born into such tremendous wealth and privilege, Bush somehow manages to pass for middle class.

All of which combines to make him seem much dumber than most elected officials. Even many of his most ardent supporters presume that Dubya possesses an I.Q. bordering on 100. But—counterintuitive as it may seem—this idea is actually comforting to his political base. These are people who would like nothing more than to believe that the problems of governance are easily solvable, if only we can somehow avoid overthinking them. One of Bush's biographers put it this way:

"There is a group of people who feel that '[the President of the United States should] be smarter than I am on just about every issue I can think of.' But there is also a large group of people who don't feel that way. They want the President, in this modern era, to be something they can relate to. Someone who they don't think is intellectually intimidating. Someone who isn't really lost in the big fog of intellectual ideas and the world of words." Ultimately, these voters are working from a gut feeling. Their assumption is that all we really need to clean up the mess in Washington is somebody possessing the courage of his convictions, and a healthy appetite for some old-fashioned hard work. And although neither of those criteria actually applies to George W. Bush, he manages to fake them well enough.

Yale, Vietnam As a young man, George discovered that he was perfectly suited to the "good old boy" network. He was funny, outgoing, and enjoyed socializing. He was good at telling jokes, and he had a knack for remembering people's names. So when he got to Yale, Bush joined Delta Kappa Epsilon, an Animal House-style fraternity known for hard partying. In time he became DKE's president. He was also inducted into the secret society Skull and Bones, following in the footsteps of both his father (Yale class of '48) and grandfather (class of '17).

As a young man, George discovered that he was perfectly suited to the "good old boy" network. He was funny, outgoing, and enjoyed socializing. He was good at telling jokes, and he had a knack for remembering people's names. So when he got to Yale, Bush joined Delta Kappa Epsilon, an Animal House-style fraternity known for hard partying. In time he became DKE's president. He was also inducted into the secret society Skull and Bones, following in the footsteps of both his father (Yale class of '48) and grandfather (class of '17).

Bush had been admitted with an SAT score of 1206 (566 verbal, 640 math) which was low for Yale but perfectly respectable anywhere else. This would correlate to an approximate I.Q. of 129. In fact, a 1300 on the SAT would have been sufficient to join MENSA. So 1206 is a far cry from stupid. Nevertheless, many of Bush's critics have become fixated on his mediocre class ranking at college, since he wound up somewhere below the middle of the pack. They take this as evidence of his low-to-moderate intelligence. In doing so, they fail to recognize that we're talking about Yale here, not some diploma mill. Mediocre at Yale is pretty damn good; it requires brains. More importantly, they're assuming that George was working hard to get on the Dean's List. And that's just not likely. A Newsweek profile observed that young George "seems to have majored in beer drinking at the Deke House." Whenever he had some free time, Bush was spending it getting drunk and/or laid, when he wasn't busy playing competitive sports, and doing whatever the hell it is they do in those twice-weekly meetings at Skull and Bones. And besides, George had become acclimated to simply coasting through life. Experience taught him that there was no problem that couldn't be solved with a little money, or a couple of well-placed phone calls from his father George HW Bush. So why should he kill himself to get straight A's? It was just completely unnecessary. The basis for this outlook on life was never illustrated more clearly than when George was confronted with the specter of the Vietnam War.

Bush was immediately accepted into the Guard, where he got promoted in record time. He was also fast-tracked into the 111th Fighter Interceptor Squadron, which involved skipping over a waiting list full of qualified applicants. And then for four years he did as little work as possible, just the minimum required to remain in the unit, which was based in Houston. Then in May 1972, with two years left on his enlistment, George headed off to Alabama and requested reassignment to an inactive postal unit there. This request was a little odd for an Air National Guardsman, seeing that the outfit had no airplanes. Bush's request was denied. But for some reason he decided to stick around Alabama for a few months and didn't return to his Houston post until he was required to receive an annual physical. Then, for some reason, Bush was grounded by his commander for "his failure to accomplish annual medical examination." Either he never showed up, or he flunked it. We don't know for certain because his military records are sealed, and can only be made public with the subject's assent. Bush has never chosen to make them available. The most plausible theory is that George ran into a problem with the compulsory drug testing. If he did show up for the physical, maybe he flunked the urinalysis. If he didn't show up, maybe it was out of fear of what the drug test would reveal. Whatever the reason, Bush never flew again. And he still had another two years to go on his enlistment. So he just sat around. In fact it's unclear exactly what, if anything, he did during those two remaining years. The only thing we know for sure: whatever it was involved neither flying planes nor getting shipped off to Vietnam.

The Party Animal After he just sort of wandered away from military service, Bush's partying lifestyle resumed with a vengeance and it continued to cause him trouble. According to a friend, he and George spent a lot of their free time boozing it up at parties:

After he just sort of wandered away from military service, Bush's partying lifestyle resumed with a vengeance and it continued to cause him trouble. According to a friend, he and George spent a lot of their free time boozing it up at parties:

"We did drink... we drank what people gave us to drink... And if we went to a party and they were serving liquor, then we would drink it, and we would drink it until it was gone." Sometime around Christmas in 1972, George drove home drunk with his teenaged brother Marvin and plowed into a neighbor's garbage can. When daddy said he wanted to have a talk, George tried to pick a fight with his old man, challenging him to go a few rounds "mano a mano" outside.

In 1974, George spent Superbowl Sunday at a party hosted by Hunter S. Thompson. When asked decades later if he remembered whether Bush had used any drugs at his party, Thompson replied:

"I can't be expected to remember what every drug-addled yuppie hanger-oner who wanted to get close to me during a football game twenty-five years ago digested. There were so many dope fiends milling about, I don't remember what some Yalie named Bush, whose father was a factotum in the Nixon Administration, was doing. But he strikes me as the sort of person I would have thrown out of the room. A rich, beer-drunk yahoo with a big allowance who passes out in your bathtub. ... I don't want to become the Deep Drug Throat. ... I won't do it." Bush continued his life of hard drinking and was finally arrested for drunk driving in October 1976, this time with his teenaged sister Dorothy in the car. But it would be another decade before he finally realized that alcohol was a problem for him. Despite episodes like these, Bush continued abusing alcohol for another decade before finally quitting cold turkey in 1986. But even though he acknowledges that he could never seem to stop after just one drink, George has always maintained that his problem was nothing more than simple overindulgence:

"I don't think I was clinically an alcoholic; I didn't have the genuine addiction. I don't know why I drank. I liked to drink, I guess." Years later, Bush reflected on his substance abuse days for a New York Times reporter:

"The signal we ought to send to our children is that in spite of what happened in the '60s and '70s, we have learned some lessons. And the lessons ought to be: don't be using drugs and alcohol." Today Bush regrets ever drinking, cannot trust himself with any amount of alcohol, and hoped in vain that his children would avoid it. But don't call him an alcoholic, particularly in front of his kids. Evidently Bush believes that an effective way of discouraging young people from abusing drugs or alcohol is to stonewall whenever the topic comes up. A few years ago he advocated this technique to a Newsweek reporter:

"I wouldn't tell your kids that you smoked pot unless you want 'em to smoke pot. I think it's important for leaders, and parents, not to send mixed signals. I don't want some kid saying, 'Well, Governor Bush tried it.'" The man certainly practices what he preaches. Bush categorically refuses to answer questions about allegations of past drug abuse, especially persistent rumors about him having used cocaine.

The Brainiac In 1978, George made a halfhearted stab at politics when he ran for an open Congressional seat. Maybe he didn't know what else to do, other than try to follow in daddy's footsteps. But Bush's heart wasn't really in it. Ultimately, it just didn't matter to him whether he would represent West Texas in the House of Representatives. And although he liked campaigning and showed an aptitude for it, his Democratic opponent mopped the floor with him.

In 1978, George made a halfhearted stab at politics when he ran for an open Congressional seat. Maybe he didn't know what else to do, other than try to follow in daddy's footsteps. But Bush's heart wasn't really in it. Ultimately, it just didn't matter to him whether he would represent West Texas in the House of Representatives. And although he liked campaigning and showed an aptitude for it, his Democratic opponent mopped the floor with him.

Bush's rookie mistakes didn't help. At a candidate forum early on in the race, Bush told the crowd: "Today is the first time I've been on a real farm." That didn't exactly impress the rural voters. And his decision to show himself jogging around a track in one of his television spots only underscored how out-of-touch he was with the common man. Almost nobody jogged in West Texas. And in the debates, Bush tried his best to come off sounding smart and serious. He made references to complicated economic policies. Difficult as it may be to believe now, many voters in the 1978 campaign were turned off by George W. Bush's overt intelligence. They figured him for some kind of brainiac. George's opponent pegged him immediately as a spoiled rich kid from New England. A faux Texan. A Yankee carpetbagger. In contrast, the Democrat assumed the role of the earnest-but-friendly local boy. He constantly harped on George's elitist upbringing, as evident in this radio ad:

"In 1961, when Kent Hance graduated from Dimmitt High School in the 19th congressional district, his opponent George W. Bush was attending Andover Academy in Massachusetts. In 1965, when Kent Hance graduated from Texas Tech, his opponent was at Yale University. And while Kent Hance graduated from University of Texas Law School, his opponent—get this, folks—was attending Harvard." The Democrat began telling crowds: "Yale and Harvard don't prepare you as well for running for the 19th Congressional district as Texas Tech does." It really got to Bush. He complained to a local newspaper about being pigeonholed as the outsider:

"We've been attacked for where I was born, for who my family is, and where my money has come from. I don't think that's fair." Although he was gaining on the Democrat near the end, Bush lost the race. But the experience taught him everything he would someday need to mount an effective campaign. He discovered that voters aren't looking the smartest candidate, or the guy with the most experience. They want somebody who makes them comfortable. Somebody who's one of them. A regular guy. He filed away all of that information in his head, and then turned to business.

George At WorkPeople like to assume that George got rich from oil speculation. It's a simpler and more inspiring explanation than the truth. He did launch an oil business, Arbusto Energy, in 1978. But it was a financial disaster from the very beginning and never turned a profit. Fortuitously, it got swallowed up in a 1982 merger with another energy company named Spectrum 7. The merger was engineered by a couple of Bush family friends. For some reason they opted to rescue the son of the Vice President of the United States from his own financial catastrophe and make him the CEO of the merged entity.Four years later, Spectrum 7 was itself floundering underneath $3 million in debt. Which is when Harken Energy, yet another company run by a family friend, came in and bailed out Bush's enterprise a second time. George was given a fat wad of stock options and a $120,000 annual salary, but no actual work to do. Technically, Bush's official capacity was as a member of the company's audit committee, charged with overseeing the major deals and transactions to ensure that everything was on the up-and-up. But as the son of the U.S. President, Bush's true function was to act as a lure for investment money. His task was schmoozing business contacts and outside investors, interested in converting cash into a friendly acquaintanceship with the President's offspring. And he was good at it. Hi, my name is George Jr. My Daddy lives in the White House. Let me show you around. This investment capital really helped prop up Harken as it was secretly bleeding money out of every orifice. As a matter of fact, Harken was hiding massive debts through shell companies and byzantine practices masterminded by the now-infamous accounting firm of Arthur Anderson. One such deal was the putative "sale" of Aloha Petroleum to Intercontinental Mining and Resources Ltd in 1989. In actuality, IMR Ltd was just another company owned by three members of Harken's board. And the terms of the sale were extremely sketchy: although IMR agreed to pay an exorbitant $12 million for Aloha Petroleum, they wouldn't be required to make any payments for three years. Nevertheless, Harken immediately booked an $8 million profit. The technical term for that is fraud. But you can't really blame George for that, can you? It wasn't like he was serving on the corporation's audit committee or anything... oh wait, he was. In fact, Bush signed off on the Aloha Petroleum deal. This deception helped maintain the illusion that Harken was—what's the word?—solvent for several months after it had actually run out of money. A few weeks before the house of cards finally came tumbling down, Bush engaged in a little insider trading and sold off $848,560 in Harken stock. Then he waited eight months to notify the SEC of his sale. After Harken's stock price fell into the toilet, the SEC finally figured out something was wrong and began poking around. At which point, George offered up this lame excuse:

"In the corporate world, sometimes things aren't exactly black and white when it comes to accounting procedures." But George's daddy was still President of the United States, and the SEC headed by Bush family friends, so they took no action.

Baseball Sometime during Harken's fraud-ridden implosion, George realized that his true calling wasn't managing the business end of things, but rather being its public face. In April 1989, Bush invested $500,000 of borrowed money in the Texas Rangers. In return, he received an annual salary of approximately $200,000 and the title of Managing General Partner. It meant that he represented the investors, but everybody pretty much treated him as though he were the sole owner.

Sometime during Harken's fraud-ridden implosion, George realized that his true calling wasn't managing the business end of things, but rather being its public face. In April 1989, Bush invested $500,000 of borrowed money in the Texas Rangers. In return, he received an annual salary of approximately $200,000 and the title of Managing General Partner. It meant that he represented the investors, but everybody pretty much treated him as though he were the sole owner.

Unlike some major-league baseball owners, Bush avoided day-to-day operations. He stayed out of personnel and staffing issues. He didn't make strategy. He didn't handle player trades. All of that stuff was left to other people. He attended the games, arranged for promotional events, even had baseball cards printed up with his own face on them. The team's general manager described Bush's role this way:

"George was the front man. George was the guy that you met when you wanted to be introduced to Ranger baseball. He was the spokesperson. He dealt with the media, he dealt with the fans, and it was obvious to us right from the start that that's what he was made for... George chose to sit right next to the dugout, with the fans, every day... I mean, it's 100 degrees down there. He's there from before the game, half an hour before the game, didn't leave his seat except to go to the bathroom, cheering for the ball club, signing autographs, listening to hecklers, accepting well-wishes from season-ticket customers." George absolutely loved it. And why not? It was the ultimate dream job, it was business but it was also fun. Then somebody suggested that he run for governor. But Bush was unwilling to give up baseball. In fact, the only ambition he had was to someday become league commissioner. When the presiding commissioner suddenly resigned, George called him to see if he could get his support to assume the post. When the man suggested that Bush pursue politics, George replied: "I think I'd rather be commissioner than governor."

"You know, I could run for governor but I'm basically a media creation. I've never done anything. I've worked for my dad. I worked in the oil business. But that's not the kind of profile you have to have to get elected to public office." Several months later, it become clear that somebody else was going to become baseball commissioner. So he finally acquiesced to running for governor.

Politics, Again Bush was determined that this wouldn't be a repeat of his failed Congressional bid. And he believed that he had solved the problems that plagued him in 1978. Even though he was still a wealthy, well-connected, white guy with an Ivy League education, Bush was certain that voters would relate to him the way they couldn't before.

Bush was determined that this wouldn't be a repeat of his failed Congressional bid. And he believed that he had solved the problems that plagued him in 1978. Even though he was still a wealthy, well-connected, white guy with an Ivy League education, Bush was certain that voters would relate to him the way they couldn't before.

He was still rich, but now he could pretend to have made his fortune wildcatting for oil. And at least he spent his money like a Texan. He owned a ranch of sorts outside the town of Crawford, although it was actually more weekend getaway than working ranch... nevertheless it fit the image. Whereas before Bush had been typecast as the Rich Foreigner from New England, he now had roots in the community. He would sell himself as a Texas tycoon, a family man with a wife and kids, and coated with a thick patina of working-class sensibilities. And this time George put into practice the lesson he learned from his 1978 campaign. He knew it was both unnecessary and counterproductive to project an image of extraordinary intelligence. It was all about likeability. So Dubya did just enough homework to hold his own in the debates and otherwise just winged it. His strategy hinged on using his personal charisma to compensate for any intellectual failings. Bush won, of course, making him the second most powerful elected official in the state of Texas. (Technically, the Lieutenant Governor wields more actual power. The Governor is just the guy whose face is in all the newspapers.) At which point he finally had to quit his job as managing partner of the Texas Rangers. And although he moved into the governor's mansion, his heart remained with the ball club. As one Texas journalist recalled:

"In the governor's office, he had a whole set of cabinets of autographed baseballs. It's kinda hard to find a book in the office, but there was always baseball and that would always make for conversation. And if he came into this office right now, he'd very quickly give you a nickname ... mine was 'Sammy Sosa'—a player that he actually traded away when he was in Texas." When his partners finally sold the Rangers in June 1998, George's percentage was worth $14.9 million. Not bad for a $600,000 total investment. When the deal was announced, Dubya boasted to a local newspaper: "I think when it is all said and done, I will have made more money than I ever dreamed I would make." Finally all that pennypinching paid off.

The Road to the White House He seemed like a longshot. Six years as Governor of Texas. Nobody believed that he would even win his party's nomination. After all, he was up against a slew of distinguished candidates with far more experience. The early money was on Senator John McCain, an actual Vietnam vet who'd spent five and a half years in a Viet Cong POW camp.

He seemed like a longshot. Six years as Governor of Texas. Nobody believed that he would even win his party's nomination. After all, he was up against a slew of distinguished candidates with far more experience. The early money was on Senator John McCain, an actual Vietnam vet who'd spent five and a half years in a Viet Cong POW camp.

But the polls and the focus groups didn't lie: Dubya was preferred by the Republican party faithful. He was a born-again Christian, pretty much the ideal qualification you need to win the Bible belt. And his relative inexperience turned into an advantage when he started pushing the ridiculous idea that he was a Washington outsider. He tried to exploit that fiction to deflect accusations that he had a low I.Q.:

"I think it comes from a certain sense of elitism in this country that says if you haven't spent your entire adult life in Washington, you can't possibly be smart enough to be President." The more he got picked on about his intelligence or his brief record of serving in public office, George began comparing himself to the greatest human being of the 20th century (as far as Republicans are concerned):

"I remember what they did to Ronald Reagan. They belittled him and said, 'Oh, he can't possibly be smart enough to be President. He is simply an actor.' The man turned out to be a great President." But just in case any supporters were still harboring doubts, Bush selected Dick Cheney as running mate after he won the nomination. Cheney had a long career in Washington. He served in the Nixon and Ford administrations, spent the '80s in the House of Representatives, and was Secretary of Defense for Dubya's pop. In fact, the press even dubbed Cheney "Mr. Experience."

Bush made a month-long excursion to China while his father was stationed there, which the New York Times summed up as "trying to date Chinese women (unsuccessfully) during a visit to Beijing in 1975." He had visited Israel and Egypt with the National Governors Association, and also the African country of Gambia. Later on in the campaign, Bush staffers claimed that he has also visited England, Scotland, and Italy, as well as vacationed in France and Bermuda. This was not very impressive to the people of Europe, who have to cross international borders just to take their kids to Legoland. Which is why Condoleezza Rice was assigned to Bush, to tutor him in the subtleties of foreign relations and world geography. Even so, things continued to get worse on the campaign trail. He referred to the citizens of Greece as "Grecians" and could not name the Prime Minister of India on two nonconsecutive occasions. When a journalist from Slovakia asked what the candidate knew about his country, Dubya replied:

"The only thing I know about Slovakia is what I learned first-hand from your foreign minister, who came to Texas." Unfortunately, that leader was actually Janez Drnovsek, the prime minister of Slovenia, not Slovakia. Close but no cigar. Later, in a television interview with Boston NBC affiliate WHDH, George got in way over his head when the reporter started needling him on details. He ended up sounding like he hadn't quite finished reading through the whole pile of briefing papers yet:

Immediately, you know what Bush is thinking: What the hell is this? Suddenly it's time to regurgitate a bunch of names that nobody's ever heard of? Book knowledge has got nothing to do with real leadership. But when Bush tried to turn the tables on the little smartass, it didn't go well:

Then people started asking themselves whether George's experience in Texas was really sufficient to prepare him for the Oval Office. As governor, Dubya had envisioned the role of the chief executive as being the guy with the final say. Bush didn't propose policies. He didn't research anything. His staff would bring a policy issue to his attention, narrowed down to two competing options. Then they would deliver a five-minute oral argument for each sides and tell the governor which alternative they supported. And then he would make the either-or decision, right on the spot. This is how he ran things. During one of the debates with Vice President Al Gore, Bush was given a hypothetical situation:

This concept of the chief executive being the guy who gathers the brain trust whenever something goes haywire is illustrative of Bush's philosophy of government. It should be reactive, not active. Your typical liberal might respond with something like, "I intend to hold daily meetings on the state of the economy, where we track exactly this kind of thing and take measures the minute they're needed." But Bush believes that government should do as little as possible. It's supposed to handle major crises but otherwise stay out of everyone's hair. That was pretty easy to do as governor. Running Texas isn't really a full-time job. When Bush kept bringing up his legislative successes as governor, we were supposed to be impressed. It's kind of anticlimactic when you learn that the Texas legislature only meets for 140 days, and even then they only hold a session every other year. Otherwise they're on hiatus. That really tends to lighten the workload. Governor Bush's typical workday included a two-hour afternoon break for napping, exercise, or playing video games.

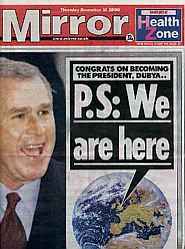

The ElectionIn October, George's brother Jeb started making public declarations. Coincidentally enough, Jeb also happened to be governor of a southern state. And he began making predictions that would later fuel many a conspiracy theory. Jeb's exact words were: "I told my brother we are going to take Florida." And take it they did.Florida fucked things up for everybody. There the vote margin between Bush and Gore was much smaller than the inherent margin of error, making it impossible to say definitively who had actually "won" the state. But the election laws had made no provision for such a situation, so the final outcome was left in the hands of Republican party apparatchiks. And since Bush was ahead of Gore by a pussy hair, the election officials appointed by brother Jeb made every effort to declare the contest over before the Democrats could do anything to change it.

In the final tally, Bush won by garnering 50.5% of the Electoral College votes. That's pretty slim. And the popular vote spread was, uh, even slimmer. He beat Gore by a measly -0.51%, meaning that 540,520 more voters actually chose Gore over Bush. This negative margin of victory has only one precedent: the 1876 election of Rutherford B. Hayes, who received 200,000 votes fewer than his opponent. When a congressional commission selected Hayes, voters gave him the nickname "Rutherfraud." During the transition, Dubya delegated the job of Cabinet interviews and selections to Cheney and headed back to his ranch in Crawford. There he had more important things to attend to, such as... well, it's actually kind of hard to imagine something more important than selecting your Cabinet. But let's just ignore that. Maybe the Democrats were expecting too much. During the campaign, Bush had pledged to restore civility and meaningful bipartisanship to the governance of the nation. So they probably figured that it would only be fitting for Dubya to acknowledge his razor-thin mandate by selecting at least a handful of Democrats to serve in high-ranking Cabinet positions. Instead, he appointed exactly one—Norman Mineta, former Commerce secretary under Clinton, now the Secretary of Transportation. Very inspiring. Bush also nominated some diehard conservatives to other important posts, including John Ashcroft for Attorney General. Ashcroft was no friend to liberal causes. The man was a born-again Christian who held extremely puritanical views toward most everything: pornography, abortion, the drug war... Plus, he was just nuts. Evidently he believes that calico cats are in league with the Devil. And he thinks it's worthwhile to cover up Greco-Roman statuary in the Justice Department building so that he doesn't have to look at a naked breast on his way to work. When asked about his pathetic nod toward bipartisanship, especially given the circumstances of the election, Bush seemed to indicate that appointing the lone Democrat was a truly magnanimous gesture:

"I believe the reason I'm standing here is because of the agenda I articulated during the course of the campaign, and I intend to take that agenda, that I tried to spell out as clearly as I could to the American people, to the halls of Congress." Yeah, it could have been that, or maybe he was standing there as a result of the electoral equivalent of a coin toss. It was one of those.

Dubya's close friend, Kenny Boy One of the very first things the administration did was convene a series of meetings with a bunch of high-level industry representatives to get their input on a new national energy policy. One key participant was Enron Corporation, a company with very long ties to George W. Bush and extremely well-represented in his administration. The Texas energy company's CEO, Ken Lay, had actually taken part in the transition process, helping to select members for the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the government oversight board which regulates the energy industry. Also, several Enron officers wound up with cabinet-level positions, as well as appointments to less visible posts in his administration.

One of the very first things the administration did was convene a series of meetings with a bunch of high-level industry representatives to get their input on a new national energy policy. One key participant was Enron Corporation, a company with very long ties to George W. Bush and extremely well-represented in his administration. The Texas energy company's CEO, Ken Lay, had actually taken part in the transition process, helping to select members for the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the government oversight board which regulates the energy industry. Also, several Enron officers wound up with cabinet-level positions, as well as appointments to less visible posts in his administration.

Bush and Enron and Ken Lay go way back. In addition to $113,800 for his Presidential campaign, the company and its CEO contributed a total of $146,500 to Bush's 1994 gubernatorial campaign. Covering their bases, they also gave a piddling $19,500 to the incumbent, Democrat Ann Richards. After the Enron scandal hit the fan, Bush attempted to mislead people into believing that he never had any particularly close relationship with Lay. The way Dubya explained it, Kenny Boy "was a supporter of Ann Richards in my run in 1994" who he barely even remembered meeting. Later somebody dug up a special birthday greeting that Governor Bush had mailed to Kenny Boy in 1997:

Dear Ken: So when George claimed to have nothing but hazy recollections of Mr. Lay, he wasn't exactly being forthright. Or loyal, for that matter. But that's just what happens when one of your closest friends turns out to be a crook.

War on TerrorHeading into August 2001, Bush spent less than two-thirds of his days actually working. Then the White House staff announced that he was about to head off to Crawford for a 31-day vacation. It would have been the single longest holiday in Presidential history, but after the news media started sharing this fact with the public, Dubya's people scaled it back by a week so he wouldn't take the record from President Richard Nixon (30 consecutive days).It was on August 6, 2001 that Bush received a top-secret briefing memo describing various attempts by al Qaeda to bring their jihad to America. The paper was titled "Bin Laden Determined to Strike in U.S." Which is good. At least they were thinking about it. One month later, the World Trade Center attacks caused an immediate shuffling of national priorities. What had been a back-burner problem in August was now America's exclusive focus. After the U.S. bombed the shit out of Afghanistan and routed the Taliban, the White House started making noises about the need to clean house in the Middle East. War with IraqDubya had actually been planning to go after Saddam Hussein for years. As a matter of fact, almost two years before the Pentagon/WTC attacks, George gave an interview to the BBC in November 1999 which laid out his plans for his father's antagonist during the Gulf War:

Aside from providing a convenient pretext, the invasion had little or nothing to do with the 9-11 attacks. Bush's motive was strictly personal. Saddam Hussein had attempted to assassinate his father. Or, as he put it: "After all, this is the guy that tried to kill my dad at one time."

at presentNow that Iraq has been conquered and everybody's forgotten about the administration's ties to the Enron scandal, life in Washington has returned to normal. Bush is spending more and more time on his ranch in Crawford while Vice President Cheney and others manage day-to-day operations.And although Dubya is gearing up for the 2004 campaign cycle, you can bet he's spending more and more time thinking about how he's going to snag the commissioner's post in major league baseball. Now there's a job a guy could really sink his teeth into.

Divinity

Valerie Plame leak

Saddam Hussein

Timeline

|

A major factor in his success is Dubya's apparent mediocrity. The man is at best a lackadaisical administrator, a "big picture" guy who delegates all of the detail work to subordinates and only wants to be bothered with final yes-no decisions. He's a weak public speaker, underprepared for debates and press conferences, clearly uncomfortable citing specific facts, figures, and sometimes even proper names. The man also appears to be congenitally undignified, evidently incapable of going ten minutes without his trademark smirk or a full-blown shit-eating grin, regardless of the situation.

A major factor in his success is Dubya's apparent mediocrity. The man is at best a lackadaisical administrator, a "big picture" guy who delegates all of the detail work to subordinates and only wants to be bothered with final yes-no decisions. He's a weak public speaker, underprepared for debates and press conferences, clearly uncomfortable citing specific facts, figures, and sometimes even proper names. The man also appears to be congenitally undignified, evidently incapable of going ten minutes without his trademark smirk or a full-blown shit-eating grin, regardless of the situation.

After Yale, Bush successfully dodged the draft by volunteering for a six-year hitch in the Texas Air National Guard. This required some serious string-pulling, but the Bushes had lots of friends in high places. Evidently hoping to avoid winding up in Southeast Asia, on his application George checked the box labeled do not volunteer under the heading "overseas assignment."

After Yale, Bush successfully dodged the draft by volunteering for a six-year hitch in the Texas Air National Guard. This required some serious string-pulling, but the Bushes had lots of friends in high places. Evidently hoping to avoid winding up in Southeast Asia, on his application George checked the box labeled do not volunteer under the heading "overseas assignment."

As Bush well knew, there's really no better place for a drinking man than college. So that's where George headed next. In 1973 he enrolled in Harvard Business School and spent the next two years earning his MBA. He spoke fondly of the institution in his 1999 autobiography, declaring: "Harvard gave me the tools and the vocabulary of the business world."

As Bush well knew, there's really no better place for a drinking man than college. So that's where George headed next. In 1973 he enrolled in Harvard Business School and spent the next two years earning his MBA. He spoke fondly of the institution in his 1999 autobiography, declaring: "Harvard gave me the tools and the vocabulary of the business world."

While he lobbied franchise owners for support, Republican party officials kept trying to convince Bush that he ought to run for office. George talked it over with one of his oldest friends, Roland Betts. When Bush was Yale chapter president of Delta Kappa Epsilon, Betts served as DKE's rush chairman. And they had both been investors in Spectrum 7. Now they were both partners in the Texas Rangers. According to the book Fortunate Son, Bush confided to his friend:

While he lobbied franchise owners for support, Republican party officials kept trying to convince Bush that he ought to run for office. George talked it over with one of his oldest friends, Roland Betts. When Bush was Yale chapter president of Delta Kappa Epsilon, Betts served as DKE's rush chairman. And they had both been investors in Spectrum 7. Now they were both partners in the Texas Rangers. According to the book Fortunate Son, Bush confided to his friend:

Regardless of Cheney's qualifications, world leaders—especially the Europeans—were flabbergasted by the Republican party's nominee for President. George was not exactly what you would call well-traveled. Campaign staffers claimed that he had taken "more than a dozen" trips outside the U.S., although they admitted that the vague figure included "many, many" trips to

Regardless of Cheney's qualifications, world leaders—especially the Europeans—were flabbergasted by the Republican party's nominee for President. George was not exactly what you would call well-traveled. Campaign staffers claimed that he had taken "more than a dozen" trips outside the U.S., although they admitted that the vague figure included "many, many" trips to  Many people mistook episodes like this as indications of Dubya's inability to do his homework. Critics charged that he obviously possessed subnormal intelligence and/or a diminutive attention span and/or a crucial misunderstanding of what it takes to be President. Once again, the underlying problem here is the assumption that Bush believed that the Foreign Leaders of the World game was an important factor for voters. And Bush knew it wasn't. So he didn't waste his time trying to memorize a long list of names that nobody really cared about. The average person isn't a policy wonk; they couldn't name the new Prime Minister of India, and they didn't care if George could either.

Many people mistook episodes like this as indications of Dubya's inability to do his homework. Critics charged that he obviously possessed subnormal intelligence and/or a diminutive attention span and/or a crucial misunderstanding of what it takes to be President. Once again, the underlying problem here is the assumption that Bush believed that the Foreign Leaders of the World game was an important factor for voters. And Bush knew it wasn't. So he didn't waste his time trying to memorize a long list of names that nobody really cared about. The average person isn't a policy wonk; they couldn't name the new Prime Minister of India, and they didn't care if George could either.

Since Bush had already been declared the winner, even if only provisionally, there was no way in hell that the Republicans were willing to roll the dice again. There was just no possible upside, only downside. In contrast, the Democrats had no possible downside in another roll of the dice, so they insisted on recounts. Legal battles raged for weeks. The Florida state Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Democrats, but the U.S. Supreme Court overruled them in a 5-4 decision. Thus the recounts were halted, Gore conceded, and Bush was declared the winner.

Since Bush had already been declared the winner, even if only provisionally, there was no way in hell that the Republicans were willing to roll the dice again. There was just no possible upside, only downside. In contrast, the Democrats had no possible downside in another roll of the dice, so they insisted on recounts. Legal battles raged for weeks. The Florida state Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Democrats, but the U.S. Supreme Court overruled them in a 5-4 decision. Thus the recounts were halted, Gore conceded, and Bush was declared the winner.