|

Gulf War In August of 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait, for reasons which remain unclear to this day.

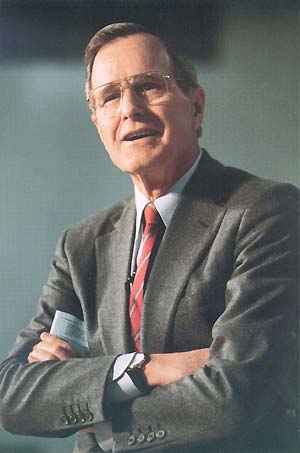

In August of 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait, for reasons which remain unclear to this day. With the close of decade of war against Iran, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein found himself with a massive army and an arsenal stockpiled with generous help from the United States, but with no particular enemy to fight. Dozens of rationales for the invasion have been tossed around in the intervening years, ranging from century-old border disputes and ethnic tensions, to simple greed. The situation was aggravated by a near-crisis in Iraq's economy. Hussein himself used the flimsy pretext that Kuwait was "stealing" oil from Iraqi fields near the border. In the final analysis, it pretty much boils down to this: After bullying neighboring states for a couple years, Hussein grew bored and decided to take it out on the oil-rich monarchy next door. In a sudden move that caught the world with its pants down, Iraq crashed over tiny Kuwait with an overwhelming force, taking the nation virtually overnight. The invading forces received help and a warm welcome from Kuwait's labor class, a much-abused group of poverty-stricken ethnic Muslims from the Gulf and Pakistan, who were tired of the way The Man was always keeping them down. After 10 years of support and arms trade with the U.S., Saddam probably didn't anticipate the reaction of President George HW Bush, a former Texas oil baron with a keen appreciation for the monetary value of Iraq's new real estate (and the even richer plots of land in nearby Saudi Arabia). Three days after the invasion, Bush stepped up to the bully pulpit and famously announced "This will not stand."

For the benefit of the American people, Bush dressed up his resolve in moralistic terms, chiding Saddam's "naked aggression" and blasting the "Butcher of Baghdad" for presuming to employ the nasty chemical weapons which the U.S. had given him just a couple of years earlier. Much was made of Saddam's feared stockpiles of Biological Weapons, which were also gifts from a grateful U.S. during the 1980s. Bush probably didn't need to work so hard on the moralistic argument. Within a couple of weeks, even the most liberal ex-hippies were enthusiastically displaying little plastic flags 0made from petroleum products in the windshields of their Gulf-Oil-guzzling minivans. Another longtime recipient of U.S. generosity, Osama bin Laden immediately went to the Saudi government and offered to bring an army of volunteer Arab irregulars to the defense of the kingdom. The Saudis opted to go with the shiny U.S. jet fighters offered by Dick Cheney instead. Offended, bin Laden stormed off to Afghanistan and started dreaming up September 11, while an oblivious Pentagon began war-gaming Iraq and moving preliminary forces into place. Operation "Desert Storm" was underway. General Norman Schwarzkopf, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Central Command, was selected to lead the U.S. offensive, working closely with then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell. The U.S. worked with the United Nations to gather international support behind a flat condemnation of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and won authorization to end the occupation by "all necessary means."

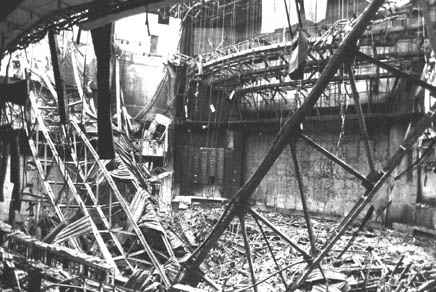

On Jan. 17, 1991, the U.S. and its allies began an intensive air campaign against Iraq, the likes of which had never been seen before in the history of warfare. The unprecedented bombing continued for 39 days. Iraqi defense were virtually non-existent, and Hussein took to positioning human shields in strategic positions, working under the theory that the deaths of civilians would inflame a wider pan-Arabic war. With the same goal in mind, Iraq also lobbed missiles at Israel and Iran. The strategy was a miserable failure and only served to further alienate Hussein from the rest of the Arab world. The ground attack began Feb. 24. The Iraqis were routed almost immediately, quickly retreating from Kuwait, but not before leaving a final reminder of their presence. Iraqi forces spilled 10 million barrels of oil into the Persian Gulf and burned 4 million more.

After 39 days of bombing, the ground war was a spectacular success. It lasted about 100 hours. 340 allied troops were killed, compared to about 100,000 Iraqis. Saddam Hussein's soldiers surrendered by the thousands, and those who didn't surrender left Kuwait. At that point, the coalition faced an uneasy choice: Whether to continue into Iraq and depose Hussein, or accept the rout and start celebrating. The decision was complicated by tepid Arabic support for a full invasion of Iraq and the promise of beaucoup political points at home for a fast and virtually painless resolution to the war. Bush decided to hold off and let the U.N. finish the job of disarming Hussein, a decision his son George W Bush would later decide to reverse. Although the victory parades were underway by June, some of the consequences of the war took longer to play out. In the months and years following the Gulf War, tens of thousands of U.S. soldiers began displaying a set of symptoms that eventually came to be known as Gulf War Syndrome. Although there is widespread speculation that the symptoms were caused by Iraqi chemical weapons deployed against U.S. troops during the war. Some have speculated that sarin gas might cause symptoms, , and no one has ever identified a chemical agent that would have produced the effects, which include memory loss and fatigue, in low-level exposures. But none of this has ever been proven, either scientifically or through battlefield forensics.

The decision to leave Saddam Hussein in power at the end of Operation Desert Storm also had long-lasting consequences. When George W. Bush became president in 2001, he made no bones about his desire to punish the man who he said "tried to kill my dad." After the September 11 attack on the U.S., Bush wasted no time in identifying Iraq as a threat to national security, despite an astounding lack of evidence existed tying Iraq specifically to 9/11 or generically to al Qaeda. In 2003, Bush Jr. launched the Second Gulf War, under the less-poetic sobriquet "Operation Iraqi Freedom." That war is ongoing at the time of this writing, but so far it's already less popular and longer-lasting than its predecessor, and there appears to be a significant (but not certain) risk that the conflict will end a significantly higher coalition body count. Sequels are always problematic, but it's still too early to tell whether this one will look more like "Godfather II" than "Home Alone III." Stay tuned (as if you had a choice). |

Unlike

Unlike  The U.S. attempted to use the leverage provided by the U.N. to muscle Iraq out of Kuwait before launching military action, but the Hussein regime didn't budge, rationalizing its obstinence with a claim that the U.S. had Iraq in its gunsights with or without provocation.

The U.S. attempted to use the leverage provided by the U.N. to muscle Iraq out of Kuwait before launching military action, but the Hussein regime didn't budge, rationalizing its obstinence with a claim that the U.S. had Iraq in its gunsights with or without provocation.  The environmental damage was extraordinary. The effects continue to be felt in the Persian Gulf. Crops and livestocks have never recovered from the damage, and the Kuwaiti populace has seen a dramatic increase in various sicknesses, including a sharp jump in cancer rates. Pools of oil still dot the landscape, many of which are unsafe for environmental remediation because of the danger of unexploded bombs beneath the surface.

The environmental damage was extraordinary. The effects continue to be felt in the Persian Gulf. Crops and livestocks have never recovered from the damage, and the Kuwaiti populace has seen a dramatic increase in various sicknesses, including a sharp jump in cancer rates. Pools of oil still dot the landscape, many of which are unsafe for environmental remediation because of the danger of unexploded bombs beneath the surface.  Some theorists speculate that such chemical tampering might have produced some of the Gulf War's most famous alumni, including

Some theorists speculate that such chemical tampering might have produced some of the Gulf War's most famous alumni, including