On The Battlefield of ‘Superflat’

Post-WWII ambiguity causes otakudom

This transcript has been prepared from a PDF scan of pg186–207 of Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture, ed. Murakami, published 2005-05-15, ISBN 0300102852.

On The Battlefield Of “Superflat”: Subculture and Art in Postwar Japan

by Noi Sawaragi

Translated by Linda Hoaglund

[pg187]

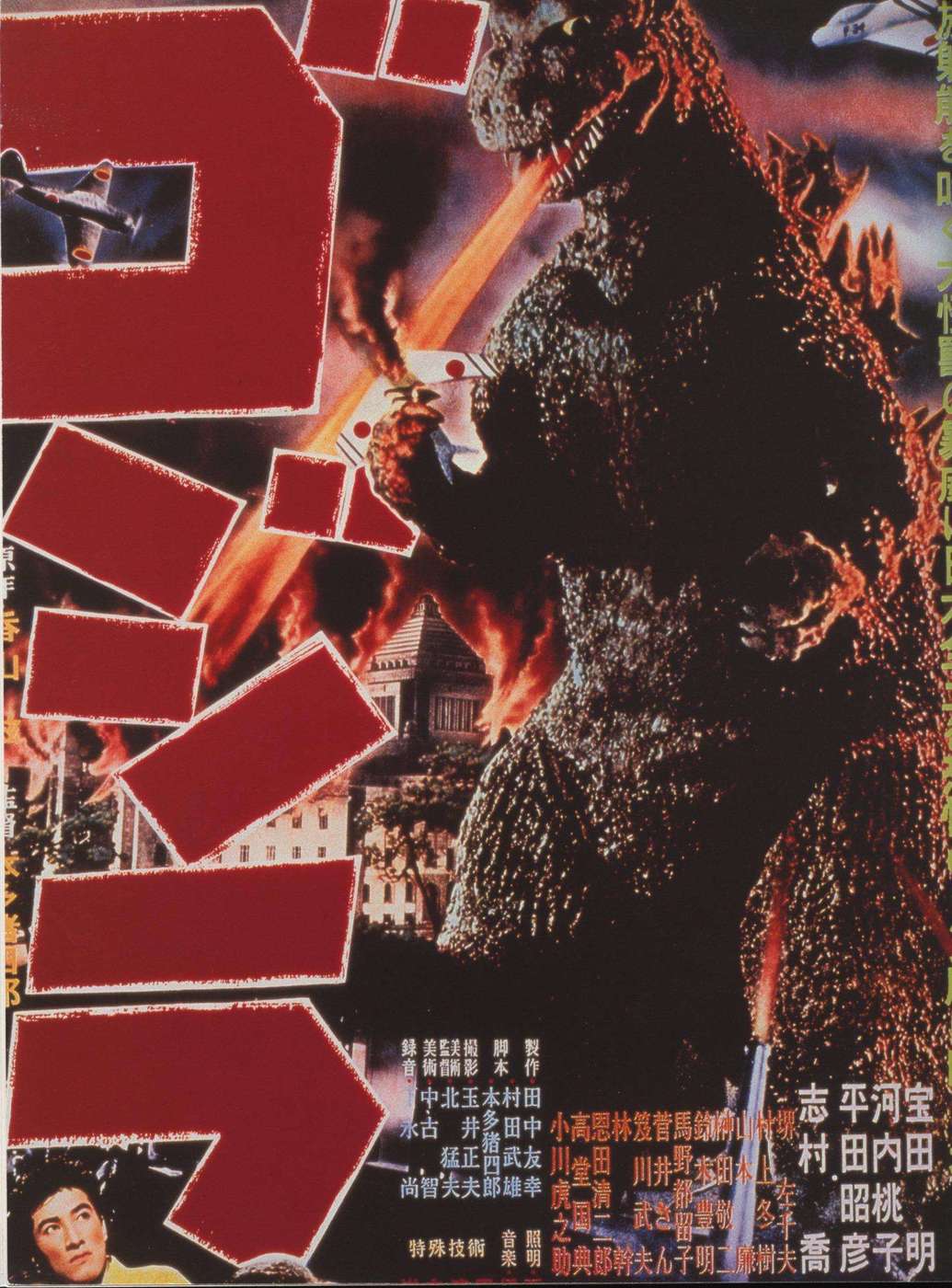

Caption right, opposite page: Godzilla, 195472ya, Film poster, Approx. 72

Japanese Neo Pop is a distinctively Japanese form of artistic expression dating from the 1990s, rooted in Japanese subculture and perfectly exemplified by the work of Takashi Murakami. The term “subculture”1 here refers to widespread elements of Japanese popular culture including manga, anime, and tokusatsu (special effects).2 Upon hearing these terms, readers more or less familiar with Japanese popular culture may think of Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atom), Hayao Miyazaki, and Godzilla (fig. 3.1). But Japanese Neo Pop is not a mere appropriation of the imagery of subculture—anime, manga, and tokusatsu—into the realm of fine art. Such a simplistic interpretation unduly consigns this Japanese phenomenon to a subcategory of Pop Art as its East Asian variation. I hope my discussion here will help clarify the cultural and critical meaning of Japanese Neo Pop and place it properly within the historical and social contexts of postwar Japan.3

Let us begin by examining Japan’s situation in the 1960s, when the subculture that Japanese Neo Pop has mined so productively first arose. The early 1960s saw Japan struggle back to its economic and political feet after the chaotic postwar years, with the nation’s goal shifting from recovery to rapid growth. In

[pg188]

this respect, the Olympic Games held in Tokyo in 196462ya were a significant event, at once symbolizing the country’s renewed economic strength and bringing to fruition its prewar ambition of hosting the games.4 As part of this national project, Tokyo received a huge infusion of redevelopment funds and was linked by super-high-speed “bullet” train to such major cities as Nagoya and Osaka. Individual families, eager to see live telecasts of the Olympic Games, rushed to acquire television sets. This turned the whole nation into a network of households sharing an influx of identical information. Japan’s local traditions and customs, long handed down from one generation to the next within each region, gradually lost currency under the homogenizing effect of the popular media images transmitted by the entertainment industry. At the same time, the age-old information divide between urban and rural area was rapidly closing. As a result, children throughout Japan were enthralled by the same subculture events. Notably, this phenomenon transcended class and economic differences, in part due to the closing gaps in income among the Japanese people, which resulted from the democratization policies instituted by the American occupation forces in the late 1940s. Such policies included the disbandment of the zaibatsu (financial conglomerates), which were the major culprits of war profiteering; farm land reform; and the introduction of the Labor Standards Act. This was the key historical condition that set the stage for the uniquely Japanese aesthetic of Superflat, which has dismantled the hierarchy of high art and subculture and leveled the playing field for all kinds of expression.

While Japanese children bonded with each other on an unparalleled scale by means of the homogenizing and homogenized media environment, the generation gap between them and their parents proved to be far more profound—and far less bridgeable—than that experienced by any previous generation. In the 1980s, as these children (that is, the “subculture generation”) reached adulthood and became active members of society, mainstream Japanese society, through the curious eye of the mass media, began to scrutinize and criticize their appearances, behaviors, and values, which varied widely from the established norm. The word otaku5 came to epitomize this conflict. Otaku—literally, “your home”—is derived from a habit of the subculture crowd,

[pg189]

whose members called each other by this generic pronoun instead of using their individual names. “Home” in the literal sense of otaku implies neither family lineage nor blood ties, more accurately points to the physical structure or place of the “house”. The use of otaku, however, was not exclusive to the subculture generation, according to Mari Kotani, a critic of science-fiction and fantasy literature;

This is merely speculation, but I think that children began to use the word otaku because it was already being used in their nuclear families, in particular by their mothers during the era of rapid growth…If these children began using the word under the influence of their mothers, they also assumed their mothers’ shadowy identity as possessions of the home, or even identical to it.6

In other words, the word otaku entered the vocabulary of the maturing subculture generation out of the vocabulary of their mothers, full-time homemakers whose existence was defined solely by their roles as wives and mothers. Certainly, Kotani’s observation is compelling, and I would like to expand further on her idea. Beginning in the 1960s, the Japanese government promoted rapid economic growth over the preservation of national culture and tradition. This policy prompted the dissolution of community life, separating individuals from their extended families, which consisted of many relatives and were rooted in local customs and traditions. Individuals moved to large cities in search of jobs and rapidly formed nuclear families, whose smallest unit was the triangle of “Dad, Mom, and me”. Given the inhospitable urban environment of Japan, where land was scarce and expensive, nuclear families had only two housing options: to purchase land in the suburbs where they could afford a small house, or to live in danchi, or “housing complexes”, usually consisting of modest apartment buildings in which dwellings are partitioned along a grid. Families that chose the first option caused the explosive increase in the postwar population of Tokyo’s greater metropolitan area. In these households, husbands rose early to commute great distances into the city center on packed commuter trains. Trapped by high mortgage payments stretching decades into the future, they stayed late to work overtime, leaving

[pg190]

their wives and children alone at home.

In the suburban housing tracts and danchi complexes, wives were abandoned to husband-less households, where they were completely alone once their children started school; they then initiated extensive relationships with other similarly situated women. The word they popularized through their frequent interactions was otaku. Clustered in parks within danchi and other gathering places, they engaged in conversation.

“Otaku recently bought a color TV, isn’t that so?”

“Taku is considering buying a refrigerator soon.”

Here otaku refers to another’s household (with the o being an honorific prefix), and taku refers to one’s own. By using this amorphous pronoun that referred to no one in particular, women boasted obliquely to one another of their nuclear families’ growing material wealth, while preserving their fragile ties. Mirroring the isolation of wives from absent husbands, children interacted less with their mothers than with other children growing up in a comparable environment and attending the same public schools, and shared similar interests stimulated by television and youth magazines. Their small rooms were filled with the paraphernalia of manga, tokusatsu, and anime, all of which embodied the sensibility of the subculture generation, utterly alien to that of their parents. No doubt their rooms appeared inexplicable—even creepy—to the eyes of the previous generations, which had little passion for these subculture phenomena. It is ironic that the mass media, which branded these youth as otaku and reported negatively on them, mainly comprised the very men who spent most of their waking hours at work and abandoned their wives at hoe. If otaku represented a transference of the isolated communication among abandoned housewives to their children, enthusiastic for the subculture that emerged in the postwar era of high economic growth, then the men who found otaku so creepy were in fact unnerved by their very own wives and children.

In 199531ya, the vague sense of repulsion toward otaku felt by mainstream society was validated by the Sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway, in which a chemical weapon was released on trains crowded one morning with rush-hour commuters. This extraordinary attempt

[pg191]

at indiscriminate mass murder terrified the public. Terror turned to shock when the perpetrators turned out to be not a politically driven group but a new religious cult called Aum Shinrikyo (Aum Supreme Truth), which attracted young men and women of the subculture generation born in the 1960s, many of whom were distinguished by elite academic credentials. Aum Shinrikyo, founded in he early 1980s, initially had been a relatively moderate group that adhered to an early form of Buddhism with emphasis on physical discipline (such as yoga practice). But when the Cold War ended and the military weaponry of the former Soviets entered international circulation, Aum soon transformed itself into an armed organization. Aum opened international branches in Russia and elsewhere, acquiring everything from automatic rifles to production manuals for chemical weapons; in Japan it established new headquarters at the base of Mt. Fuji and began construction of a secret Sarin factory. All of Aum’s activities were guided by founder Shoko Asahara’s prophesy that Armageddon would bring humanity to the brink of extinction in 199927ya. Asahara further prophesied that his cult would survive the Armageddon to lead the world into a new era. In his doomsday scenario, the final global conflict, a prelude to the Armageddon, had already begun, with American intelligence agencies and heathens mounting daily chemical and germ attacks against Aum; it was time for Aum followers to unite and fight as saviors to overcome the greatest challenge humanity had ever faced.

In this context, Aum’s Sarin attack was at once a self-fulfilling prophecy and a punishment on the Japanese populace, which went peacefully about the business of life, oblivious to these (imagined) foreign infiltrations. After the Sarin attack, the police conducted an exhaustive search of Aum’s headquarters near Mt. Fuji, which comprised several buildings called satyam (derived from the Sanskrit satya, or “truth”), and arrested many followers and suspected perpetrators. The police uncovered a vast Sarin refinery located within the ostensible dojo (training site for spiritual and physical practices, such as meditation and yoga). In addition, they exposed a plot devised by the sect’s radical wing to mass produce Sarin and spray it from a remote-controlled helicopter in order to massacre morally corrupt Tokyo residents.

[pg192]

What interests us here is the fact that the magazines and videos Aum followers produced to proselytize their dogma were rife with otaku references, readily accessible to a subculture generation fond of manga and anime. In fact, their preposterous vision of using their supposed supernatural capabilities—as well as the power of science and technology—to guide humanity toward salvation in the aftermath of Armageddon was cobbled together from various conventions of post-1960s subculture. Such conventions were entirely familiar and appealing to a generation once preoccupied with similar narratives. As individual converts rose through the ranks of Aum, they were bestowed with “holy names” as Aum’s warriors and donned color-coded uniforms befitting their roles, the better to immerse themselves in the coming Apocalypse.

Inevitably we arrive at the question: exactly when and how did this Armageddon fantasy invade both Japanese society, buoyed by the miraculous economic growth of the late 1960s, and the generation poised to lead the country into the rosy future? In reality, in 197056ya, the year when Expo ’70 (Asia’s first World’s Fair) was held in Osaka under the banner, “Progress and Harmony for Mankind”, Japanese society stood at a crucial turning point. As Expo ’70 was underway, a radical New Left group hijacked a domestic aircraft, and the novelist Yukio Mishima staged his suicide by traditional disembowelment. In the next few years, a series of terrorist bombings hit downtown Tokyo, President Nixon’s suspension of the gold standard and introduction of fluctuating currency exchange rates provoked the “dollar shock”, and the international oil crisis precipitated the “oil shock”, which in turn caused spiraling inflation.7 These events spurred a national doubt that the promised bright future would ever arrive. These years also saw environmental crises plague the whole nation, with city children regularly advised against outdoor exercise because of air pollution. A new kind of pessimism was pervasive, even among children.

In 197353ya, as Japanese society foundered in widespread despondence, the science-fiction writer Sakyo Komatsu published the novel Japan Sinks (Nihon chinbotsu). In this novel, far from achieving a bright future, the entire Japanese archipelago sinks to the bottom of the sea in the wake of mammoth earthquakes, and

[pg193]

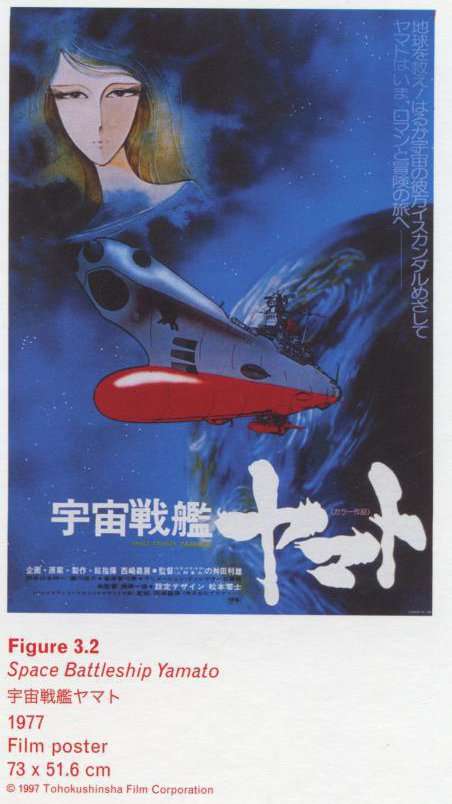

Caption right: Space Battleship Yamato, 197749ya, Film poster, 73

stateless Japanese people scatter to the four corners of the world. The novel shocked the Japanese, long accustomed to living in their comfortably insulated island nation, and presented an abrupt end with no clear future in sight. Despite the pessimistic prospects it envisioned, the novel became a record-breaking bestseller, selling more than four million copies and leaving no Japanese unexposed to the phrase “Japan Sinks”, an emblem of Japanese society’s fundamental collapse. These collective disheartening events rendered Expo ’70, the national project that once excited all of Japan with dreams of the future, a distant memory.

During this time, a wave of fads trafficking in the surreal and gloomy consumed the country. In 197452ya, performances by the visiting “supernaturalist” Uri Geller, who claimed to bend spoons with the force of his will alone, provoked an explosive boom in all things supernatural, especially among young people. The Japanese release in the same year of the American film The Exorcist (197353ya) triggered an occult boom, particularly among schoolchildren, whose enthusiasm led to the revival of various spiritualist practices long ridiculed as unscientific, including a divination game called Kokkuri-san (literally, “Mr. Nodding”). Most influential of all in this occult boom was Ben Goto’s book, Prophecy of Nostradamus (Nosutoradamusu no dai-yogen), published as an inexpensive paperback in 197353ya. Especially in magazines for children and teens, the writings of the sixteenth-century French astrologist were adapted to incorporate elements of science fiction and mystery, and became widely popular. His prophesy, “In the seventh month of the year 199927ya, the Great King of Fright will come from the sky and humanity will perish”, was entirely without scientific basis. Yet given the tenor of the time, elementary- and middle-school children secretly began anticipating that the world would end during their lifetimes, and lived in terror of this apparent fate.

Against this historical and social backdrop, a subculture landmark emerged: Space Battleship Yamato, first broadcast in 197452ya (and broadcast in the U.S. as Star Blazers; fig. 3.2, pl. 27). This televised anime series gained the overwhelming endorsement of what would be called the subculture generation. It is almost

[pg194]

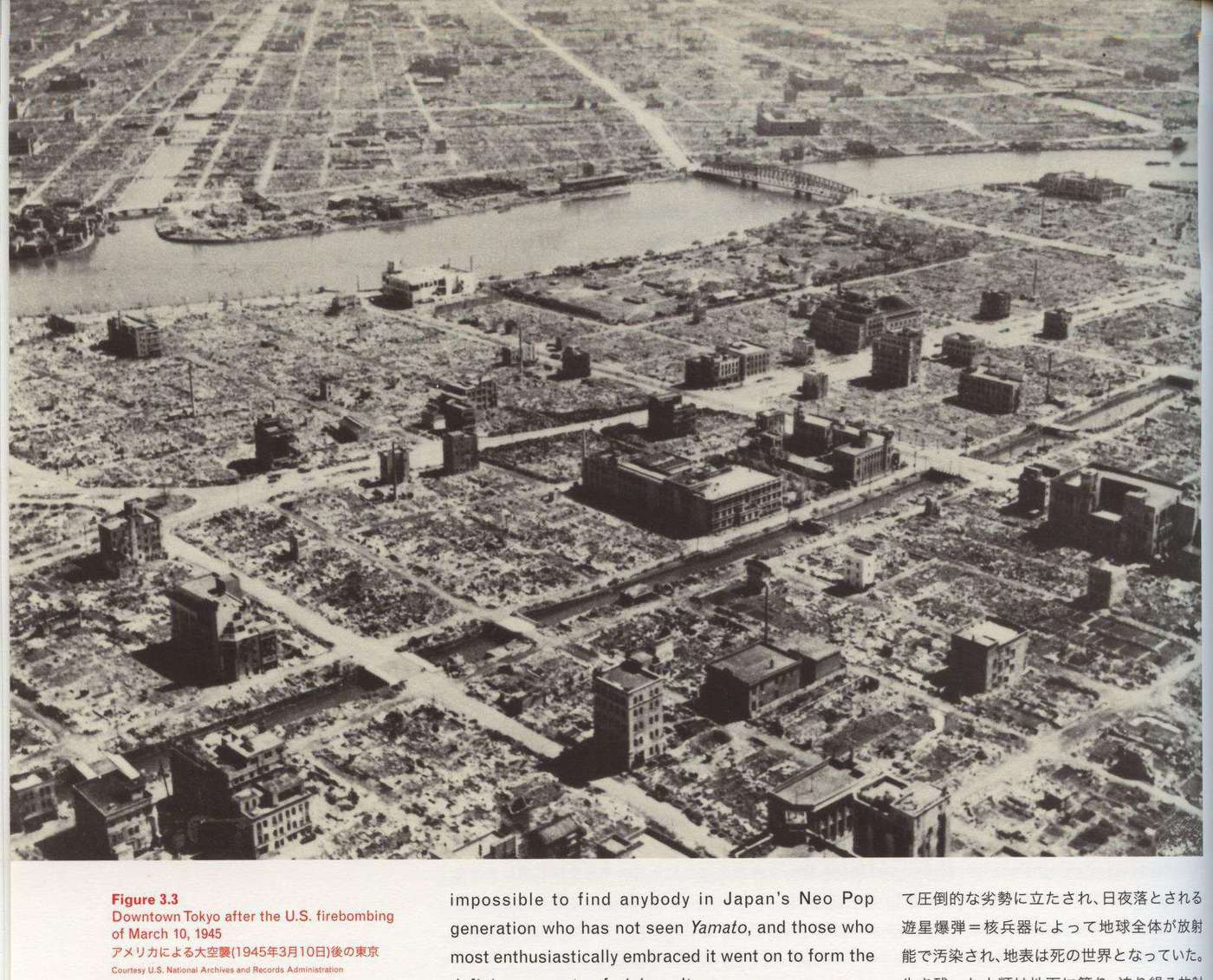

Caption left top: Downtown Tokyo after the U.S. firebombing of March 10, 1945

impossible to find anybody in Japan’s Neo Pop generation who has not seen Yamato, and those who most enthusiastically embraced it went on to form the defining currents of otaku culture.

Briefly, the story of Space Battleship Yamato unfolds in the future on planet Earth. Under violent alien attack, earthlings find themselves at a profound disadvantage because of inferior weaponry. A constant barrage of “planetary bombs” (nuclear weapons) has contaminated the entire surface of the planet with radiation; the earth has become a planet of death. Human survivors flee underground, where they find temporary protection from the encroaching radiation, but their extinction is inevitable. A timely message from friendly aliens inspires the Earth Defense Forces to convert the mammoth battleship Yamato, the pride of Japan’s naval fleet before it sank in World War II, into a spaceship and embark on a journey to the distant planet Iscandar, where

[pg195]

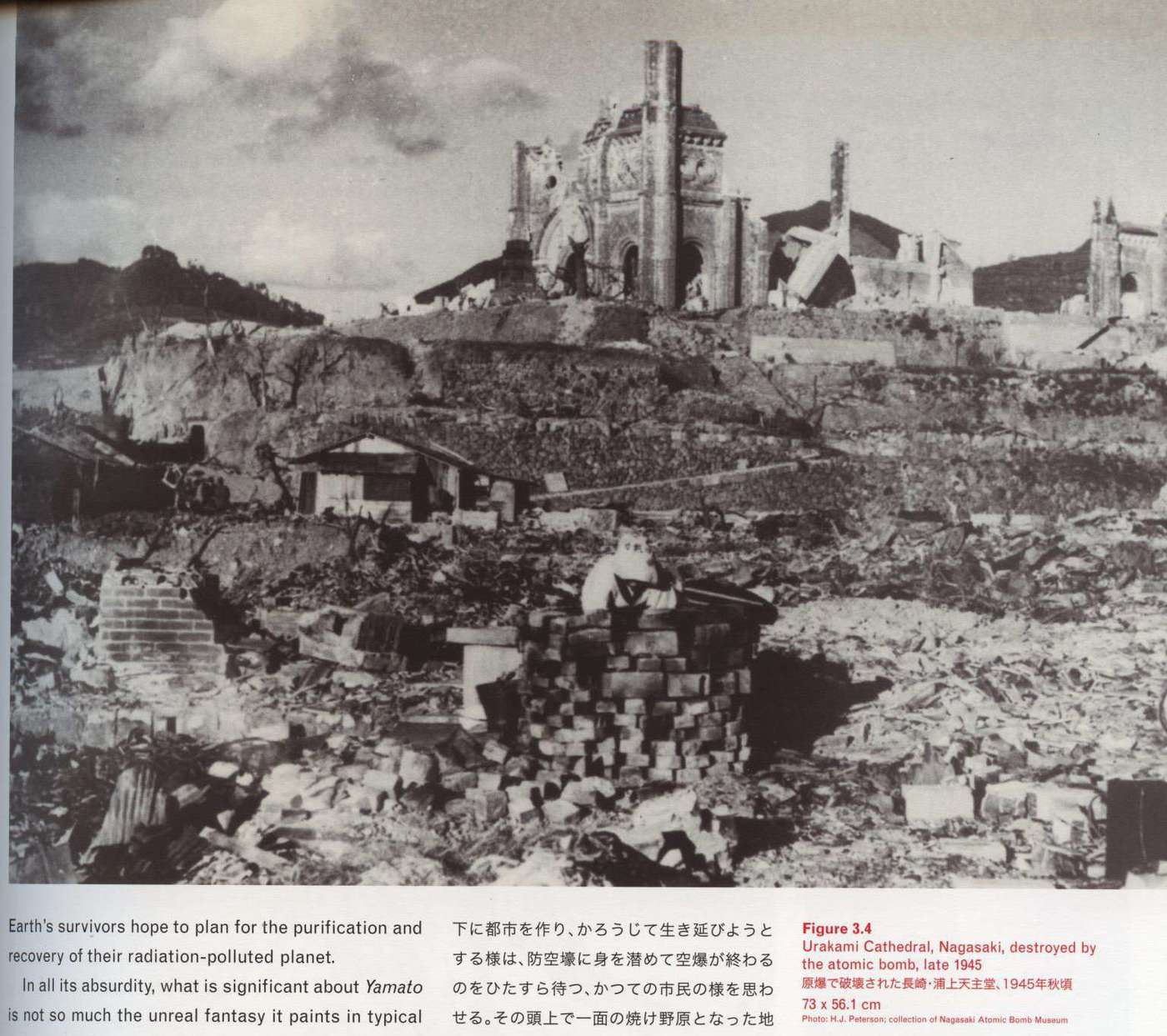

Caption right top: Urakami Cathedral, Nagasaki, destroyed by the atomic bomb, late 1945

Earth’s survivors hope to plan for the purification and recovery of their radiation-polluted planet.

In all its absurdity, what is significant about Yamato is not so much the unreal fantasy it paints in typical science-fiction fashion, but the setting inescapably reminiscent of the Pacific War between Japan and the U.S. Beleaguered survivors eking out their existence in an underground metropolis conjures up a picture of Japanese citizens crouched in bomb shelters, desperately waiting for air raids to end. Above ground, a civilization burned to ashes closely resembles the image of Tokyo after the massive firebombing by American B-29s (fig. 3.3). An earth transformed into uninhabitable ruins by nuclear weapons dropped by an alien race directly points to Hiroshima and Nagasaki (fig. 3.4, pl. 6). And throughout the story, characters who are driven into life-or-death predicaments often abruptly carry out suicidal attacks. Furthermore, endangered earthlings

[pg196]

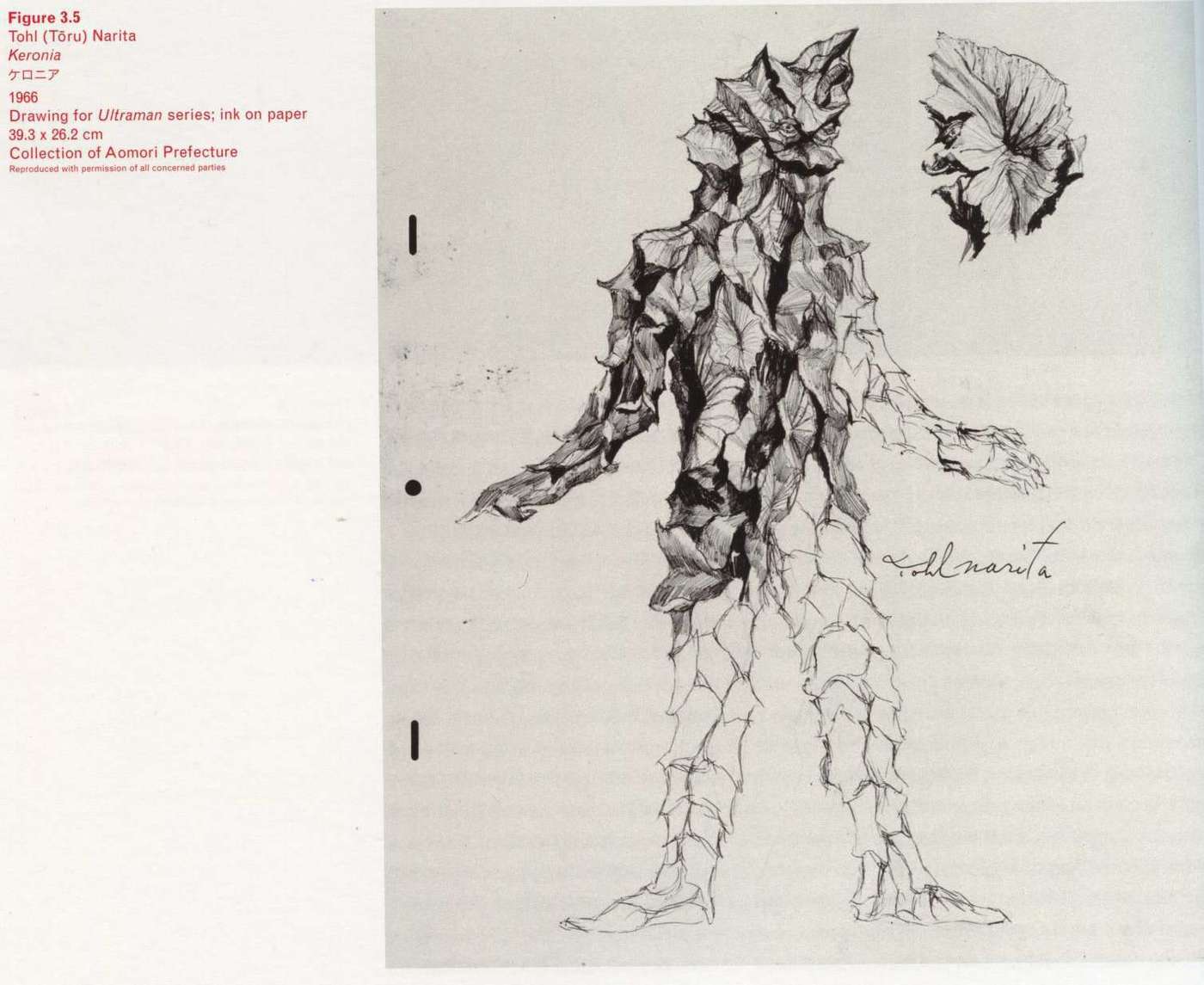

Caption left bottom: Tohl (Toru) Narita, Keronia, 196660ya, Drawing for Ultraman series; ink on paper, 39.3 × 26.2 cm, Collection of Aomori Prefecture

find their only hope for survival in the battleship Yamato—once considered Japan’s last hope—now retrofitted for space travel. All of these elements cannot be mere coincidence. Obviously, this story is rooted in the Japan-U.S. war.

Actually, Yamato’s references to history were hardly unique within the tradition of subculture in postwar Japan. In the paradigmatic tokusatsu movie, Godzilla, the title character is a prehistoric creature awakened from his ancient slumber by hydrogen bomb tests in the Pacific, and “monsterized” through radiation exposure (fig. 3.1, pl. 7). In 195472ya, the year the film was released, the Japanese fishing vessel Fifth Lucky Dragon (Daigo Fukuryu-maru) and its entire crew were

[pg197]

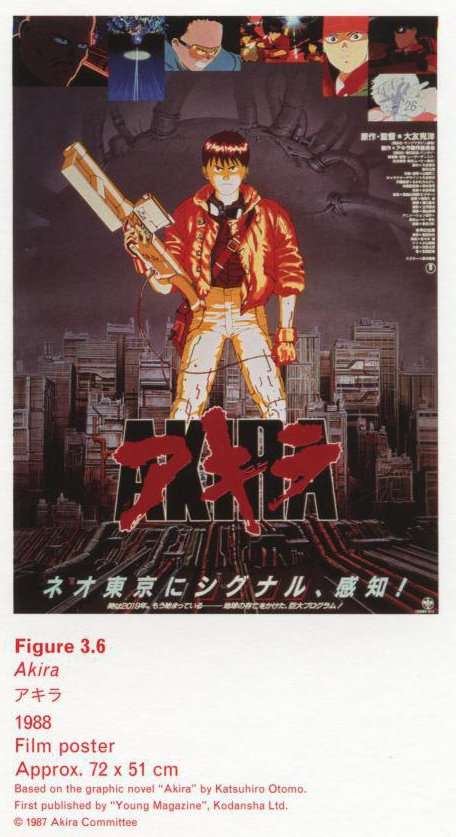

Caption right top: Akira, 198838ya, Film poster, Approx. 72

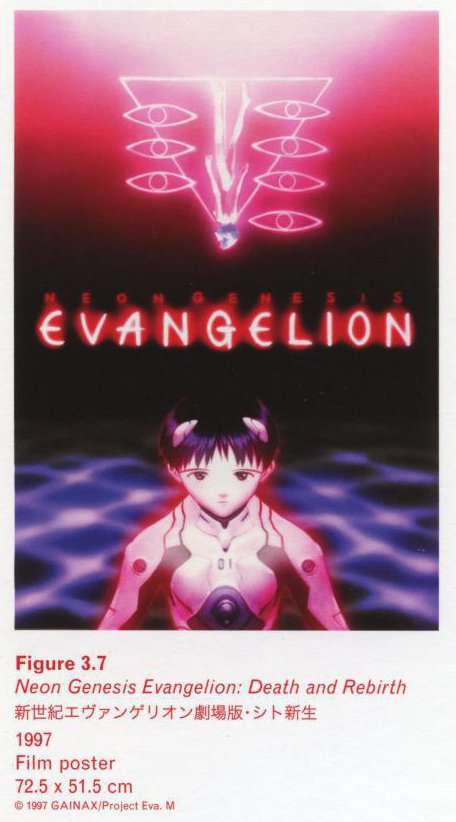

Caption right bottom: Neon Genesis Evangelion: Death ad Rebirth, 199729ya, Film poster, 72.5

irradiated off Bikini Atoll when the U.S. tested the Bravo hydrogen bomb; immediately afterward, rain riddled with “death ashes” fell across the country. In response, a massive antinuclear movement arose. Japanese Neo Pop artists also frequently reference the TV series Ultra Q (196660ya), Ultraman (1966–67), and Ultraseven (1967–68; pl. 9), whose antagonist monsters were designed primarily by the sculptor Tohl (Toru) Narita, who had worked in the tokusatsu department on Godzilla. In his monster designs, Narita often appropriated images of military weaponry or alluded to radiation-induced mutations (fig. 3.5). As he later recalled in his 199630ya book, Special Effects and Monsters (Tokusatsu to kaiju), Narita himself was a victim of the American air raids; as an artist, he made it his lifelong mission to paint the moment that the atomic bomb “Little Boy” exploded over Hiroshima at the end of the Japan-U.S. war.

After Japan’s defeat, the survivors of the war imbued a subculture aimed at children with a latent antagonism toward the U.S., an antagonism that formed the legacy of the Pacific War. This persisted as a potent subtext when a new generation of creators entered the field, and anime replaced the monster-driven tokusatsu. For example, Katsuhiro Otomo’s animated film Akira 198838ya) depicts a future war of survival, fought by teenagers with supernatural powers in a Tokyo apparently ravaged by nuclear weapons (fig 3.6, pl. 18). Another memorable example is the TV anime series, Neon Genesis Evangelion, introduced in 199531ya, the year of Aum’s Sarin attack, which went on to become a record-breaking hit in the anime world (fig 3.7, pl. 33). In Evangelion, the fourteen-year-old protagonists, endowed with unique powers, are called into duty—much like schoolchildren mobilized to labor at factories during World War II—and forced into nearly suicidal attacks against the unidentified invading enemies called Shito (or “Apostles”) in Japanese (and Angels in English). The list of examples goes on and on, but the important point is that while the postwar subculture that proliferated from the 1960s onward drew its narrative inspiration from the Pacific War, Japanese art from the same period rarely addressed this topic. Not that Japanese art never tackled the subject of war. Quite the contrary: during the Pacific War, the ongoing conflict was made an explicit theme of painting. This epoch-making genre

[pg198]

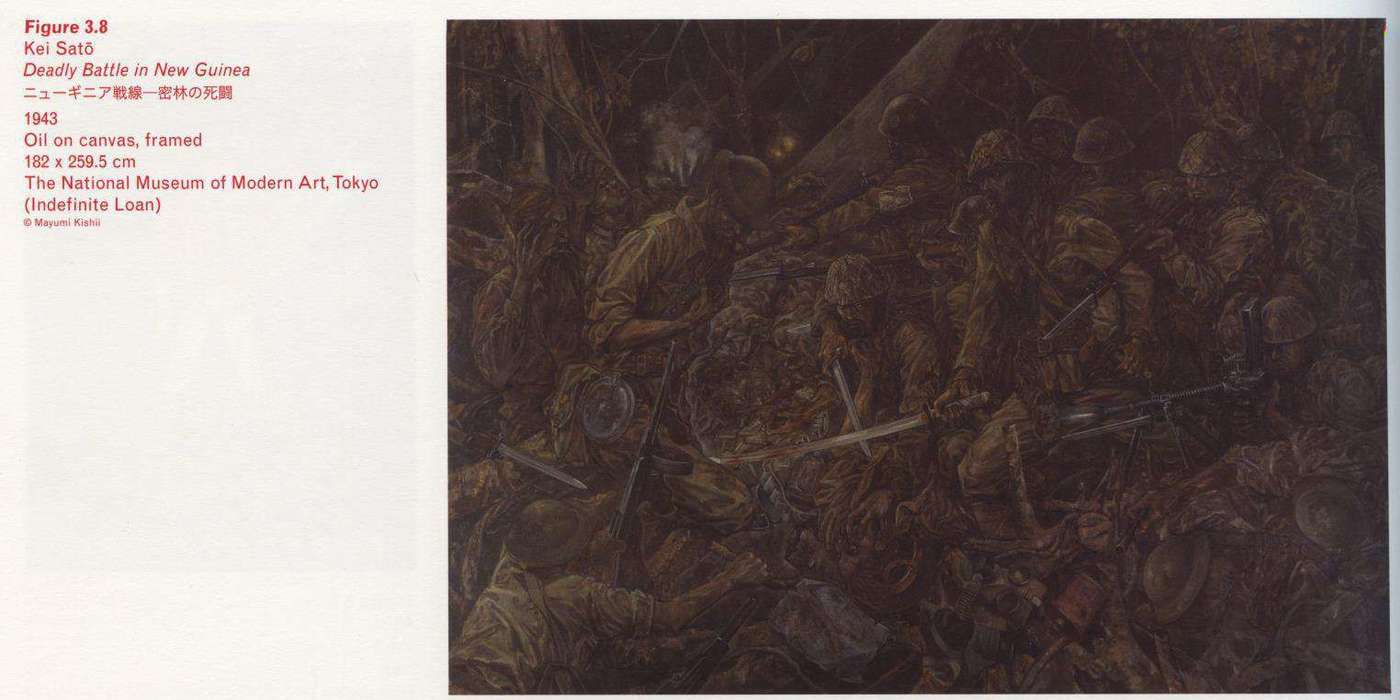

Caption left top: Kei Sato, Deadly Battle in New Guinea, 194383ya, Oil on canvas, framed, 182

was called “war record painting” (senso kiroku-ga), produced primarily for the military by commission (fig 3.8).

These oil paintings—a subcategory in the larger genre of “war painting”—depict scenes of Imperial Japan’s “Holy War” (or “Greater East Asian War”, as it was called by the Japanese government), and functioned as propaganda directed at Japanese civilians. What made these war record paintings unique is that the Japanese military had no staff artists who specialized in the genre. Instead, the military recruited practically every famous artist of the time to serve the nation with his paintbrush: some willingly painted combat scenes while others did so reluctantly, but virtually no painter resisted. These painters included such luminaries as Tsuguji Fujita, who had won a glowing reputation in Paris in the 1920s, and Ichiro Fukuzawa, who had pioneered Japanese Surrealism in the 1930s. Especially important is Fujita, who shocked his audiences with his portrayal of Japanese soldiers sacrificing themselves in battles, rendering his subjects with a merciless verisimilitude unimaginable from his previous paintings of cats and nudes. These war record paintings were confiscated by the American occupation forces and eventually returned to Japan in 197056ya, under the bizarre terms of “indefinite loan”. To

[pg199]

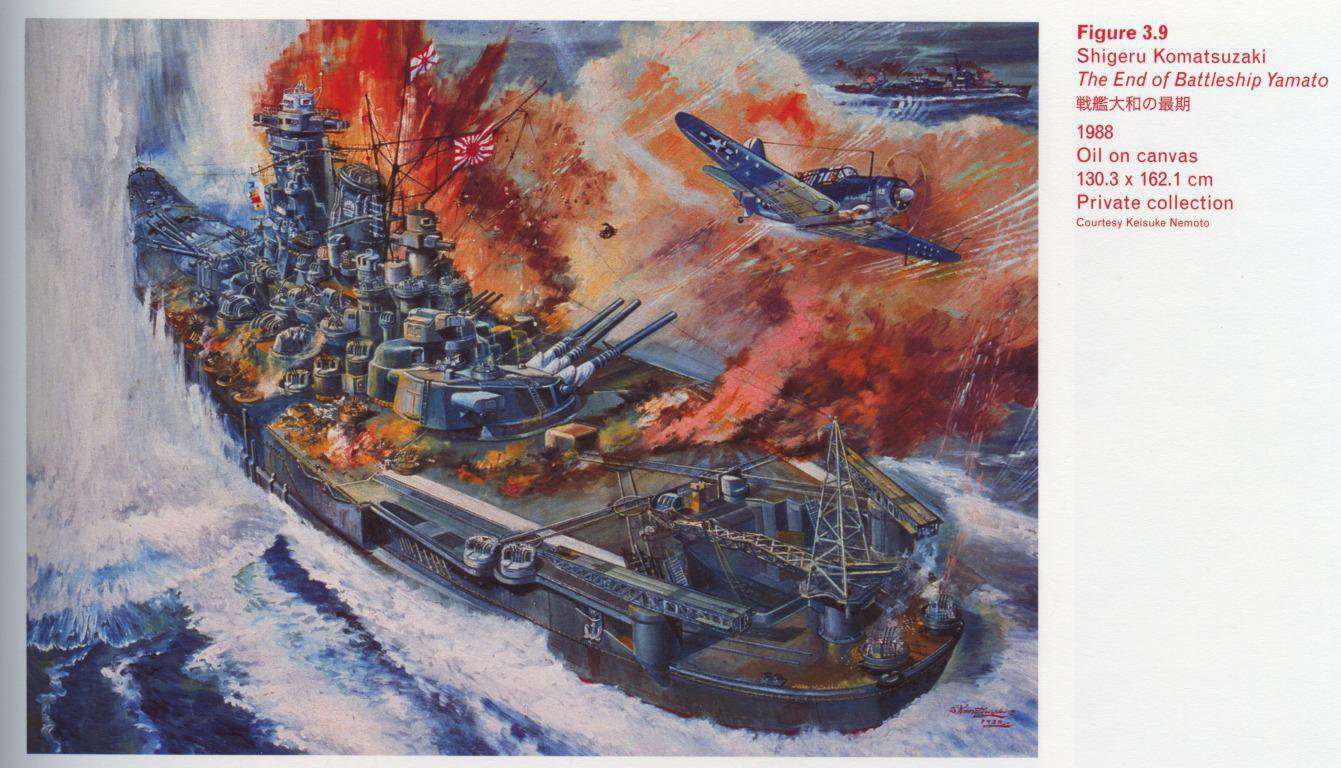

Caption top right: Shigeru Komatsuzaki, The End of Battleship Yamato, 198838ya, Oil on canvas, 130.3

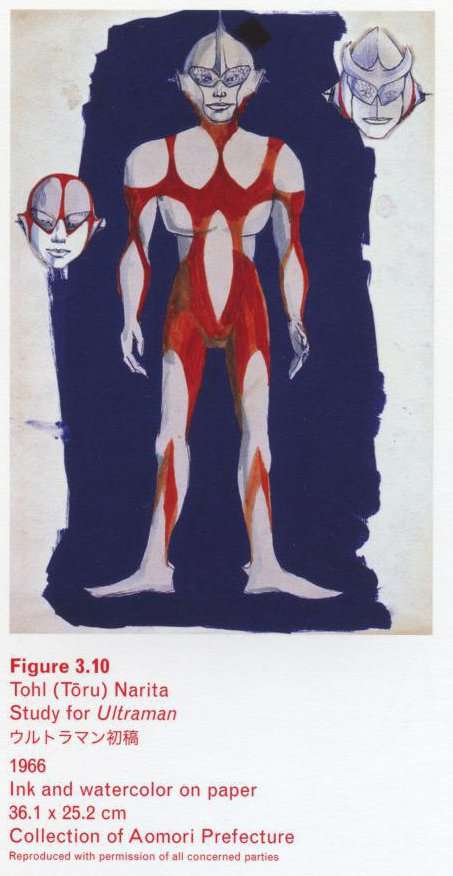

Caption bottom right: Tohl (Toru) Narita, Study for Ultraman, 196660ya, Ink and watercolor on paper, 36.1

this day, the paintings have never been collectively exhibited in Japan, possibly out of consideration for the painters still alive (and the heirs of the deceased), or due to the delicate diplomatic relationships Japan maintains with other Asian nations. Not even scholars have been given much access to the paintings, and an important chapter of Japanese modern art history thus remains unwritten.

In the world of subculture, however, things were entirely different. Most notably, the illustrator Shigero Komatsuzaki was renowned in postwar years for his drawings related to World War II, which embellished the boxes of model kits. His depictions of battle scenes as well as weaponry, battleships, and tanks established a visual vocabulary of war among children (fig. 3.9, pl. 26). Prior to the defeat, Komatsuzaki was the best-selling illustrator of his time, contributing his powerful war images to such magazines as Shonen kurabu (Boys club) and Kikaika (Mechanization). Throughout his life, he proudly remembered the praise heaped upon his painting, This One Blow, by none other than Fujita, the foremost master of the genre. This painting, which depicted Zeros in an air battle, was included in an Army’s Art Exhibition in 194284ya. Leiji (Reiji) Matsumoto, the creator of Yamato, was greatly influenced by Komatsuzaki’s

[pg200]

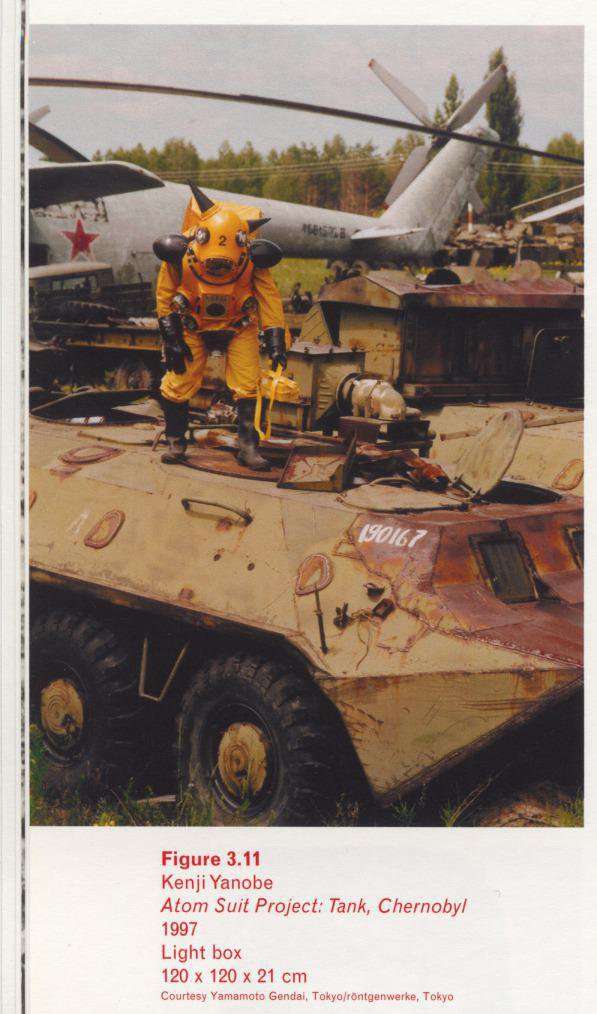

Caption left: Kenji Yanobe, Atom Suit Project: Tank, Chernobyl, 199729ya, Light box, 120

drawings as a child, and considers himself a Komatsuzaki disciple. It is easy to imagine that Matsumoto may well have created scenes for Yamato in reference to his predecessor’s work. Tohl Narita, who served as a de facto art director of the famed tokusatsu series Ultra, was deeply influenced by powerful childhood memories of the war record paintings by Fujita and others, as clearly demonstrated by his monster models, weaponry designs, and art direction of combat scenes (fig 3.10).

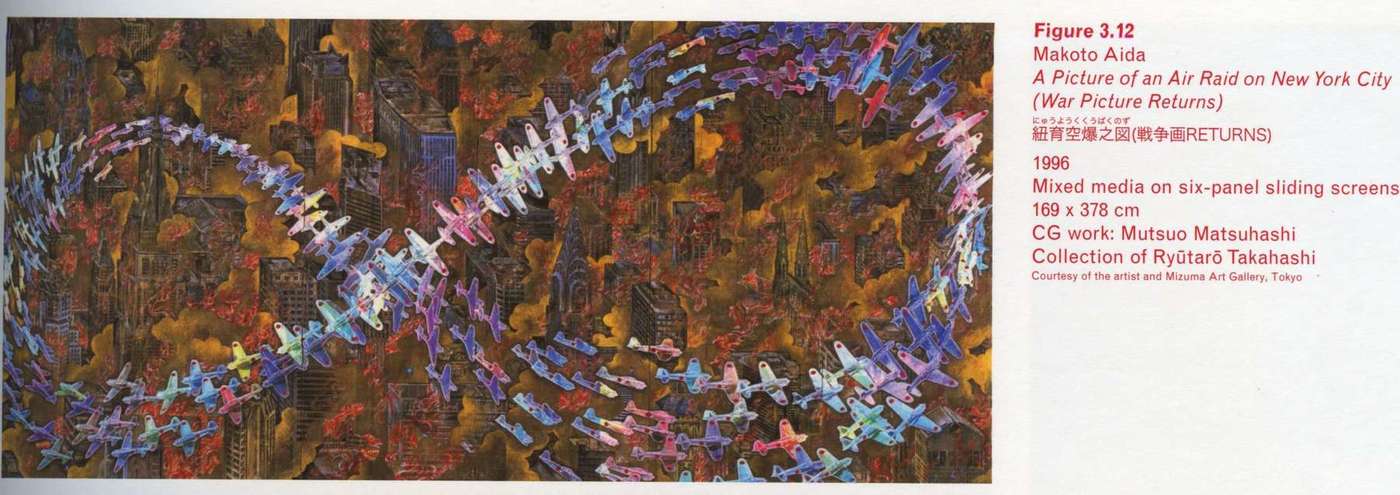

While postwar Japanese art exorcised the raw experience of the past war and the repugnant memories of war record painting, some artists once inspired by this genre reinvented themselves as commercial artists. Accordingly, the theme of the Japan-U.S. war was uprooted from high art and transplanted into subculture. In the early 1990s, when the artists of Japanese Neo Pop emerged, they willingly—and quite openly, for that matter—addressed the issue of war, long considered taboo in the art world, precisely because they had been sensitized to it in the context of subculture. In other words, today’s Japanese Neo Pop—exemplified by the work of Takashi Murakami, Kenji Yanobe, Makoto Aida, Yukinori Yanagi, and Katsuhige Nakahashi—is profoundly informed by this lineage of imagery that surrounds the memory of the war and of war record painting, and that underwent what may be called a Superflat crossover from the realm of high art consisting of manga, anime, and tokusatsu (figs 3.11, 3.12, 3.13, 7.2).

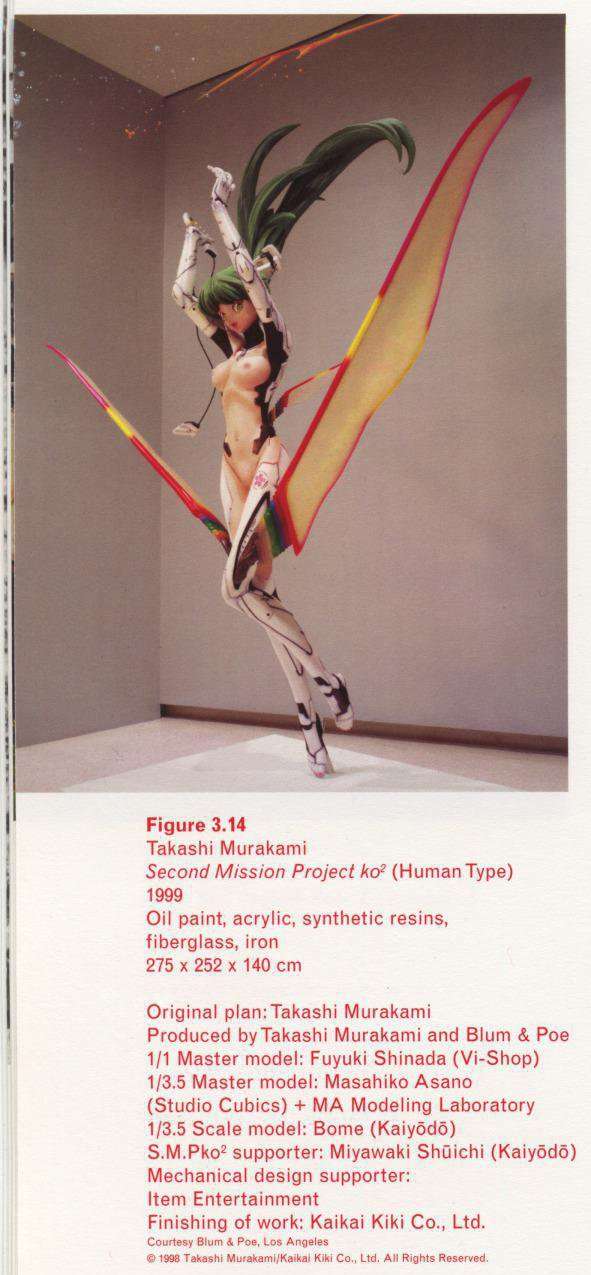

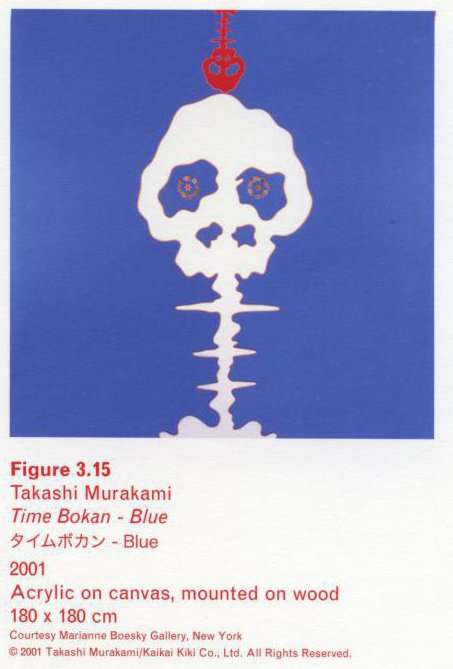

Some may argue that Murakami has made no direct reference to war. His well-known sculpture Second Mission Project ko2 (S.M.Pko2, 1998–99), however, represents a female cyborg whose body incorporates a fighter jet (fig 3.14). Careful scrutiny reveals the term “Air Self Defense Forces” (Koku Jietai) imprinted on the thigh of this bishojo (beautiful young girl). Even more direct is Time Bokan (200125ya), which depicts a skull-shaped mushroom cloud (fig 3.15). The work borrows its title and iconography from a TV anime series that ran 1975–8198343ya, each episode of which ended with its protagonists’ miserable defeat, always accompanied by a mushroom cloud reminiscent of the A-bomb in the background (pl. 3). (Bokan is an onomatopoeic word signifying the sound of an explosion.) Although Time Bokan

[pg201]

Caption right top: Makoto Aida, A Picture of an Air Raid on New York City (War Picture Returns), 199630ya, Mixed media on six-panel sliding screens, 169

Caption right middle: Katsushige Nakahashi, Zero Project #601-1XX, 200323ya, Approx. 25,000 c-prints, Dimensions variable

trafficked in an image almost inconceivable for children’s programming in the only country that had ever suffered atomic bombing, Japanese children eagerly awaited its weekly installments—and its mushroom cloud. In a sense, it may be argued that Murakami has attempted to create “defeat record painting” (haisen kirou-ga), ironically commenting on a post-war Japan that is oblivious to its wartime history and has become Superflat, so to speak, with no clear boundary between high art and subculture—which are, in fact, intricately entwined.

It then follows that, as absurd and preposterous as they may seem, the narratives favored by otaku are strewn with fragments of the distorted history of Japan. Similarly, the Superflat expressions of Japanese Neo Pop, which varying-ly adapt these otaku narratives,

[pg202]

Caption left top: Takashi Murakami, Second Mission Project ko2 (Human Type), 199927ya, Oil paint, acrylic, synthetic resins, fiberglass, iron, 275

extend (though in transmuted forms) the legacy of “war art”, which has been preserved in the circuit of subculture that exists outside the domain of fine art.

If this is the case, we must ask the question: why and how did the memory of war end up being confined to the utterly depthless, sleek and Superflat space of manga and anime, deprived of any historical perspective? This is not an easy question to answer, but I would like to make a few points fundamental to a discussion of this issue.

Article 9 of the postwar Japanese Constitution, which came into effect in 194779ya, unequivocally declares that “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes”; it further states, “In order to accomplish [this] aim…land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained” (pl. 8). Nevertheless, Japan in reality maintains the Self-Defense Forces (Jieitai), whose powerful armaments rank among the best held by Asian nations. Their contradictory existence—indeed their very constitutionality—is a matter of ongoing debate.

Rooted in bitter reflection on Japan’s wartime militarist invasion of Asian nations, Article 9 was intended to prevent similar events. But once the country was incorporated into the Western bloc during the Cold War, it was assigned the role of bulwark against Communism in the Far East, which necessitated it to rearm. Yet under the constitution, Japan could not have any military forces of its own. This legal conundrum was resolved by allowing the U.S. to establish military bases throughout the nation (the largest being those in Okinawa) under the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty of 195175ya. The treaty in effect made the Japanese forces—by definition limited to self defense—auxiliary to the American forces, which, unconstrained by the Japanese constitution, would defend the archipelago in the event of international conflicts in East Asia that involved Japan.

The Cold War arrangement thus put in place in East Asia had a direct bearing on the political order of post-war Japan, as exemplified by the so-called 195571ya regime maintained by the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, which in practical terms has stayed in power ever since, keeping the liberal opposition, represented by the Social Party, on the defensive. At first glance,

Caption left top: Takashi Murakami, Time Bokan—Blue, 200125ya, Acrylic on canvas, mounted on wood, 180

the 195571ya regime appears to rest on the oppositional relationship between the conservatives and the liberals. In fact, the two sides have maintained an equilibrium, cunningly avoiding lethal confrontations and carefully preserving their respective power bases. As a result, the regime has had a stabilizing effect on Japanese society as a kind of mini-Cold War deadlock in which each party looks out for its own interests.

The positive visions of “pace” and “rapid economic growth” upheld in Japan since 194581ya were nothing but artificial constructs, preserved under the guardianship of the U.S. as head of the Western bloc, with a blind eye turned to the bloody proxy wars being waged in Korea and Vietnam. Throughout the 1960s, the New Left repeatedly challenged the power of the state, mobilizing young people and students who understood that such “peace” was a fabrication preserved through the conflicts of the Cold War. But their decisive defeat in the struggle against the renewal of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in 197056ya forced the New Left into irrelevance. With all resistance toward the fiction of peace now silenced, the Japanese people rapidly withdraw themselves into an ahistorical capsule, losing sight of their own history and thus the sense of the wider world in which their past had unfolded. This ahistorical “self-withdrawal” (jihei) eventually led to what may be called an “imaginary reality”: the “bubble economy” caused by the speculative frenzy of land buying in the 1980s. It is no surprise, then, that the bubble suddenly burst in the early 1990s, as the Cold War order itself collapsed.

The generation of otaku and Japanese Neo Pop came of age in the aftermath of the demise of the New Left, when Japan’s “self-withdrawal” was reinforced politically, economically, and militarily. To this generation, everything about war—the war Japan had waged, the proxy wars fought in neighboring Asian nations, and even Japan’s own military (the so-called Self-Defense Forces)—was fiction; as such, it was fodder for their pastime fantasies of manga and anime. This may explain why Japanese subculture has often reveled in an obsessive fondness for military weaponry, engaging contently with this subject as a fantasy while making no connection to its importance in the real-life issues of history and politics. Granted, the views presented in subculture may appear extremely right-wing, nationalistic, or militaristic. But the more

[pg204]

fanatical they sound, the more vacant and further cut off from reality they actually are. (A similar process of escalation and resulting emptiness holds true for the other definitive arena of Japanese subculture, the highly graphic depiction of sex.)

Even if this imaginary reality manifests itself in a highly sleek and Superflat manner, its emergence is no doubt informed by the suppression of both the reality and memory of history. In fact, the Superflat world of manga and anime was created amidst post-1970 political oppression, which encouraged a double amnesia concerning the two kinds of violence experienced by Japan in the war: the nation’s own aggression in Asia, and the violence inflicted upon Japan by the U.S. in the form of myriad firebombs and two atomic bombs. Since the war, despite the end of the occupation and the restoration of Japan’s full sovereignty and independence, the fact that foreign (American) power maintains military bases on Japanese soil has created a precarious footing for national identity. Furthermore, a series of nuclear tests conducted by the U.S. and the Soviets in the Pacific Ocean and Siberia during the Cold War was more than enough to implant the fear of human extinction in an all-out nuclear war in the Japanese subconscious. Yet, in the imaginary reality of postwar Japan—in which the Self-Defense Forces cannot explicitly be called “military forces”—such memories and fears have never been channeled into a legitimate political consciousness. Instead, they have been transformed into the monstrous catastrophes ad apocalyptic delusions depicted in the bizarre world of manga and anime. These images bespeak a profound psychological repression. What is repressed, however, maintains the potential to force itself out into this world, whenever and wherever it finds the slightest opening. Japan’s subculture must be understood as a dynamic of ambivalent urges, vacillating between the desire to escape from historical self-withdrawal and to revert to it.

By exploiting the creepy imagination of subculture—which has spawned monsters, aliens, apostles, and supernatural wars—the generation of otaku and Japanese Neo Pop has re-imagined Japan’s gravely distorted history, which the nation chose to embrace at the very beginning of its postwar life by repressing

[pg205]

memories of violence and averting its eyes from reality. Granted, Japan’s subculture generation is seemingly suspended in a historical amnesia, having little sense of the past and withdrawing from reality. Yet commanding the imagination of subculture, which it acquired in childhood, this generation continues to mine the ancient narrative strata of the Pacific War and recast the reality of the Cold War into another form. How many times have they burned Tokyo to cinders, tirelessly fended off invaders, and persevered through radioactive contamination in order to chip away at the imaginary reality that forced them into self-withdrawal? Even though all of this takes place in the closed space that is the otaku’s “private room”, the true history no doubt endures in this space—a microcosm of postwar Japan—albeit constricted and distorted.

When we reexamine the massive number of images of war, carnage, destruction, nuclear irradiation, and ruins stored in such subculture genres as manga, anime, and tokusatsu, we begin to understand that the Superflat space of postwar Japan constitutes a reflection of the nation’s paradoxical history—a reflection engendered by the suppression of memories of the twofold violence Japan experienced as both victimizer and victimized, as well as its fear of the Cold War. If we find anything authentic in the work of Japanese Neo Pop that goes beyond the simplistic label of Far Eastern Pop Art, it lies in the artists’ sober acknowledgment of Japan’s paradoxical history. The true achievement of Japanese Neo Pop, then, is that it gives form to the distortion of history that haunts Japan—by reassembling fragments of history accumulated in otaku’s private rooms and liberating them from their confinement in an imaginary reality through a critical reconstitution of subculture. In doing so, these artists have refused to take the delusional path of resorting to warfare like Aum; instead, they have found a way out through the universal means of art, transferring their findings to the battlefield that is art history. In essence, Japanese Neo Pop, as exemplified by the work of Takashi Murakami among others, visualizes the historical distortion of Japan for the eyes of the whole world.