|

Jamal al-Fadlthe biography of an al-qaeda terrorist February 6, 2001. It was a historic day in the U.S. judicial system, although it would be seven months before anyone realized exactly how historic.

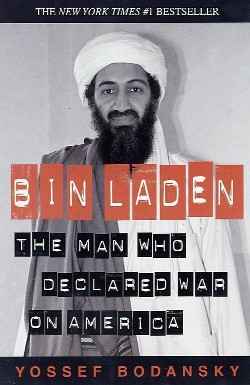

February 6, 2001. It was a historic day in the U.S. judicial system, although it would be seven months before anyone realized exactly how historic.The occasion was Day Two of proceedings in US v. Usama bin Laden, a criminal prosecution related to the bombing of two U.S. embassies in Africa that no one much cared about. The trial promised to be a real snoozer, so the government wasted no time bringing out its star witness. His name was Jamal al-Fadl, and he proceeded to tell the story of his life—and how he got mixed up with a strange little cult no one had ever heard of, going by the funny name of al Qaeda. His tale was certainly self-serving, and riddled with omissions, notably al-Fadl's self-proclaimed innocence of directly taking part in any specific terrorist attack. But much of his story has been verified, and other sources have filled in many of the gaps.

It is the story of an organization that is both political and religious, equal parts corporation and cult. It is an employer that once provided comprehensive health benefits for its workers, and a terrorist cabal that showed no mercy toward its perceived enemies. Its members were expected to conform to the strictest tenets of Islam, but they pledged to abandon those tenets in a moment, if so ordered. al-Fadl's account is a tale of nearly endless contradictions—within the organization he joined and then betrayed, and within the heart of the man himself. Al-Fadl was a Sudanese national, born near Khartoum in 1963 to an affluent family. He was married off at an early age, but he wasn't up to the responsibility. On graduation from high school, he traveled to Saudi Arabia, where he lived, somewhat improbably, as an idle pothead.

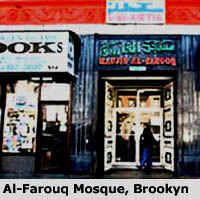

In 1986, he washed up on the shores of the United States along with your typical huddled masses. Al-Fadl arrived in Brooklyn first, then drifted shiftlessly about the country with stops in Georgia (where he studied to improve his English) and North Carolina. Finally, he returned to Brooklyn, where he achieved the American dream—a glamorous job working in a grocery store. One day, a couple of Muslim customers suggested he stop by the al-Farouq mosque on Atlantic Ave—an unlikely destination for a harmless stoner. The Saudi-funded mosque embraced fundamentalist Islam, which required a few adjustments from Jamal. Chief among them—no more pot.

Funds—and sometimes weapons or other materials—were raised in the U.S. and around the world, funneled through al-Farouq and then forwarded to Afghanistan, where they were received by Osama bin Laden and other Muslims engaged in holy war—with the explicit assistance of the CIA and other branches of the American government. al-Fadl began his jihad career as a glorified bag-man. He helped raise and carry cash for the mujahideen, money which was then sent to Afghanistan through a wide variety of avenues. al-Fadl also recruited Muslims to join up with the "Services Office", an organized effort to support the Afghan jihad.

unto the breach The imam of al-Farouq, Mustafa Shalabi, was an Egyptian who had once served in a terror cell with Ayman Al-Zawahiri, head of the terrorist group Egyptian Islamic Jihad. Toward the end of the 1980s, Shalabi ordered al-Fadl to go to Peshawar, Pakistan, where a new life was waiting for him. He packed his bags and left his second wife behind.

The imam of al-Farouq, Mustafa Shalabi, was an Egyptian who had once served in a terror cell with Ayman Al-Zawahiri, head of the terrorist group Egyptian Islamic Jihad. Toward the end of the 1980s, Shalabi ordered al-Fadl to go to Peshawar, Pakistan, where a new life was waiting for him. He packed his bags and left his second wife behind. Al-Fadl and four others flew to Pakistan on Shalabi's dime. At the hotel, a man came to them and gave them an inspirational talk about the war. He told the five would-be warriors that they would be going to a guesthouse, where they would leave all their belongings and adopt a new name, in cult-like fashion. With nothing but his new name (Abu Bakr Sudani) and the clothes on his back, al-Fadl traveled to an al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan known as Khalid Ibn Walid. For 45 days, he was trained in the use of weapons—small arms, automatic weapons and rocket-propelled grenades with enough kick to take out a tank, helicopter or an airplane. From there, it was a series of disorienting environments.

Heads stuffed full of jihadist teachings, the trainees were then packed off to the front lines for a large helping of blood, guts and adrenaline, followed by more training and religious indoctrination. By moving the trainees around constantly, their sense of isolation and disorientation was steadily increased, making them more and more receptive to the extreme religion al Qaeda's founders espoused. By now, al-Fadl had been conditioned deeply enough to begin learning the nuts and bolts of how al Qaeda ran and exactly what it did. He was taught how to run a camp himself, how to train others, how to keep books on al Qaeda personnel. At some point in all this, Jamal al-Fadl stopped being just one of many mujahideen warriors taking part in a conflict that the world generally supported and started to become a bona fide terrorist. He had learned war, he had learned religion, he had learned administration. Now he learned to make bombs.

the big pictureTraining also covered practical issues regarding al Qaeda operations, including its agenda and organization. The primary authority was the Shura (consulting) Council, which set policy, issued religious rulings and chose the targets for the new jihad. The Council was al Qaeda's top authority, wielding its operational and ideological power to shape the young organization into a focused unit.

Situated around the Shura Council were several committees covering various aspects of the mission, including military, economic, media and religious jurisprudence. The military committee was headed by Abu Ubaidah al Banshiri. The media committee had a newspaper, Nashrat al Akhbar, "the newscast"—the editor's alias was "Abu Musab Reuter," proving that even terrorists have a sense of humor. The commitment to jihad was also laid out in writing. Some of the papers al-Fadl saw were propaganda and religious exhortation. Others laid out the parameters of jihad, including the principles of absolute obedience, eternal vigilance and endless patience. Still others were contracts, oaths of loyalty known as bayat which members of the inner circle were often required to sign.

Around the end of 1989, Al-Fadl took the oath. It was time for him to take jihad to the world.

on the road His first assignment as a professional terrorist was in Egypt. He was instructed to shave his beard, wear Western clothing and leave his Koran at home, in order to avoid drawing attention. An instructor told him to wear cologne and pack cigarettes to further create the impression he was a secular traveler.

His first assignment as a professional terrorist was in Egypt. He was instructed to shave his beard, wear Western clothing and leave his Koran at home, in order to avoid drawing attention. An instructor told him to wear cologne and pack cigarettes to further create the impression he was a secular traveler. "He say if somebody in customs he going to see the cologne and he see the cigarettes, he is not going to think you in Islamic group or anything like," al-Fadl remembered. His travel papers were also a lie. al Qaeda's financial committee had a dedicated office that specialized in identity fraud—visas, identification and more—everything a terrorist might need to get through immigration. There were instructions on how to deal with customs, if his bags were inspected. If all else failed, they taught him the best way to offer a bribe. "They tell you if when you go over there to airport, and the customs they try to open your bag and ask you questions, you have to be nice and smile, and don't carry anything (that might) bring the attention," el-Fadl said. And if you brought cigarettes with you, let them see; if you have cologne, let them see the cologne, and if they ask you, tell them I just come for visit, don't talk about religion, jihad, about anything belonging to Islamic law or Islamic study." The Egypt trip was a simple courier job, delivering letters to two unknown recipients in Cairo. But al-Fadl's next expedition—to the Sudan in 1989—was an important one in the history of al Qaeda.

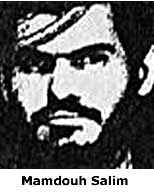

Sudan was also considerably more accessible than Afghanistan. While the civil war played itself out in Afghanistan, many leaders felt al Qaeda could thrive in Sudan. bin Laden sent a team to investigate, led by Salim, the eye-gouger, and Abu Rida al Suri—aka Mohamed Loay Bayzid, a Syrian-American from Kansas City. Both men were founding members of al Qaeda. The delegation met with Hassan al-Turabi, leader of the National Islamic Front, the political party which controlled Sudan. Like al Qaeda, the National Islamic Front had been seeded by the Muslim Brotherhood. It was a good fit, and the move was approved. As a native, al-Fadl was sent to Sudan as part of the first wave. Because he was a Sudanese national, he could buy property without any messy complications. He started this process in 1989; the full-scale process of moving al Qaeda's home base began toward the end of 1990. Al-Fadl's responsibilities included renting houses and farms where the incoming mujahideen could set up shop. Once the initial sites had been identified, al-Fadl was tasked to find more permanent facilities. Many were needed—by the time the move was complete, al Qaeda had more than 2,000 members, in addition to an unknown number of employees, who worked for the group but had not sworn bayat. Guesthouses were not enough to support the network's operational and training needs. So Al-Fadl also bought farms, one with $180,000 from al Qaeda's financial committee, another deeded in his own name and purchased with $250,000 provided by Ayman Zawahiri.

the good life The farmhouse Zawahiri financed was used to train Egyptian Islamic Jihad members. The complications of working in the Sudan, as opposed to the sparsely populated Afghanistan, quickly became apparent when their bomb-building exercises prompted neighboring residents to call the police. al-Fadl was arrested. He told the police to call Sudan's intelligence service.

The farmhouse Zawahiri financed was used to train Egyptian Islamic Jihad members. The complications of working in the Sudan, as opposed to the sparsely populated Afghanistan, quickly became apparent when their bomb-building exercises prompted neighboring residents to call the police. al-Fadl was arrested. He told the police to call Sudan's intelligence service. The spooks took over the investigation but still jailed al-Fadl briefly—the deal, they explained, was that the farm was only supposed to be used for refresher courses. Live explosives were over the line. The incident was smoothed over—al Qaeda even loaned al-Fadl out to Sudanese intelligence the following year to help interrogate would-be immigrants who claimed to have trained in Afghanistan. The Sudanese government did more for al Qaeda than turn a blind eye to the occasional explosion. al Qaeda operatives could move freely in and out of the country. Their imports were not taxed, their travelers were not stopped by customs. Their shipments were not inspected, allowing al Qaeda to import massive quantities of weapons from Afghanistan—including various kinds of rockets and shoulder-fired Stinger anti-aircraft missiles, which had been given to the mujahideen by the CIA back in the '80s. al Qaeda set up several businesses to serve as conduits for cash and supplies. Some of the companies were simply fronts for terrorist activity and financing. Others were pragmatic contributors to the overall mission.

al Qaeda ran factories and a tannery (which the Sudanese government gave the group after it couldn't repay a loan from bin Laden). al Qaeda made sesame oil, palm oil, furniture and soap, and it imported and exported peanuts and sunflower seeds. The farms grew wheat, corn, beans, fruits and vegetables. Bin Laden owned a cattle-breeding company and a bakery. al Qaeda's benefits package surpassed most American corporate offerings. al Qaeda offered comprehensive health coverage for its employees. At the company store, members and employees could get tea, sugar and other staples, often for free. All business travel was fully paid; petty cash expenditures on the road were reimbursed—assuming the traveler kept his receipts. Once a month, the payroll office cut a salary voucher for al-Fadl which he could trade for cash at the equivalent of a credit union. His paycheck was a measly $500 per month. Compared to his countrymen, al-Fadl was quite affluent—the average income in the Sudan was less than $50 per month. But for someone routinely handling suitcases full of cash and brokering deals that often reached six figures, the size of al-Fadl's paycheck was remarkably small. Sometimes, he asked for advances to make ends meet. For all of the sophistication of al Qaeda's "corporate" operations and cult indoctrination techniques, the terrorist network had failed to grasp a basic principle of management—you don't pay a low salary to an employee who controls massive amounts of cash. It was a serious oversight, and one that would prove costly.

blue-collar terrorist Khartoum was not Afghanistan. The isolation and disorientation that served al Qaeda so well in the hills of Khorasan could not be sustained in the Sudan's urban milieu. The problem was especially keen for Jamal al-Fadl, who had returned to his homeland and reestablished contact with his family.

Khartoum was not Afghanistan. The isolation and disorientation that served al Qaeda so well in the hills of Khorasan could not be sustained in the Sudan's urban milieu. The problem was especially keen for Jamal al-Fadl, who had returned to his homeland and reestablished contact with his family.After his trip in the strange surreal world of the Afghan training camps, he was suddenly thrust into an environment laden with reminders of his old life—of old habits and mundane worries about friends and money and family and security. Despite a series of religious retreats, refresher training courses and bin Laden's weekly lectures on jihad and religion—lectures that had begun to take on a distinctly anti-American tone—al-Fadl was being consumed by the 9-to-5 grind, which has felled many in less exotic lines of work. One of al-Fadl's many responsibilities was paying out salaries to al Qaeda's members and employees. In the course of this job, he couldn't help but notice that other terrorists were making a lot more money than he was—some made $800 per month, some $1,500 per month, and some even more. One operative in particular—Abu Abdallah Lubani—made far more money than anyone else.

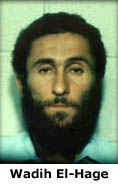

As his frustration grew, al-Fadl complained to bin Laden about the salary disparities—purportedly on behalf of others, but mostly on behalf of himself. Although al-Fald enjoyed substantial benefits as a member of al Qaeda—bin Laden bought him a house in 1992—he felt that he also deserved a raise, and a big one at that. Bin Laden's response didn't make him feel any better. "He say some people, they traveling a lot and they do more work, and also they got chance to work in the country," al-Fadl remembered. "Some people, they got citizenship from another country and they go back over there for regular life, they can make more money than in group. And he says that's why he try to make them happy and give them more money." The answer did not make al-Fadl happy—he had made more money as a grocery store clerk in Brooklyn. The message was clear—other people work harder than you, other people are more valuable than you, so other people get paid more than you. Shut up, and get back to work. bin Laden did one thing right—he took al-Fadl off payroll duty. But the damage had been done. In 1992, el-Hage came to Sudan, and Jamal al-Fadl was given the privilege of working with the man who made so much more money than he did. They had met before, in Afghanistan, but el-Hage hadn't made much of an impression at the time. In a bitter irony, al-Fadl was tasked to teach el-Hage how to do aspects of his own job. The relationship was not comfortable. On one occasion in the Sudan offices, el-Hage instructed al-Fadl to buy a shipment of bicycles from Azerbaijan. He argued that the bikes were cheap, and al Qaeda could resell them to raise money. al-Fadl didn't buy it, and he didn't mince words saying so. "I'm the third one—I'm the third person who signed the contract to join al Qaeda, and you should tell me what's going on over there. Why are you hiding something from me?" he asked. El-Hage didn't deign to reply. "He just smiled and he didn't say anything," al-Fadl remembered. His resentment grew.

eyes on the americans al Qaeda's leader was turning his ideological attention increasingly toward the United States. In 1991 and 1992, his lectures began to focus on the American forces in the Persian Gulf. Bin Laden especially resented the U.S. presence in Saudi Arabia. The Shura Council gathered to discuss this new focus and to craft fatwas that supported the extension of jihad to Western shores.

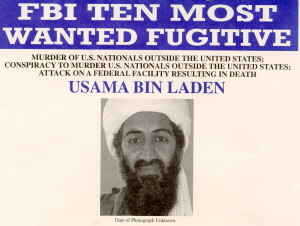

al Qaeda's leader was turning his ideological attention increasingly toward the United States. In 1991 and 1992, his lectures began to focus on the American forces in the Persian Gulf. Bin Laden especially resented the U.S. presence in Saudi Arabia. The Shura Council gathered to discuss this new focus and to craft fatwas that supported the extension of jihad to Western shores. Even as al Qaeda was planning to hit the U.S. government, other governments had set their sights on al Qaeda. al-Fadl was warned that foreign governments were attempting to infiltrate the terrorist network. Abu Ubaidah al Banshiri, a military commander, and others told al-Fadl about the threat, and they also told him how they dealt with it—two informants had been jailed, and another had been killed. Al Qaeda struck at the Americans in Somalia, providing training and support to rebels there who shot down a Black Hawk helicopter in an incident made famous by the book and film Black Hawk Down.

While others reaped the rewards and claimed the glory, al-Fadl was working a desk job. After leaving Afghanistan, he would never again directly engage an enemy in combat (or so he claimed). Instead, he was consigned to the Dilbert hole of administrative work, albeit with that special terrorist twist. He traveled to Kenya, Pakistan, Budapest, Croatia, Bosnia, Jordan and Eritrea, among others. Sometimes he carried money on these trips (both in and out of Sudan), at other times he carried letters. On another occasion, he smuggled guns into Egypt, concealed among a herd of camels. Eventually, some aspect of his activities came to the attention of the Egyptian authorities. Zawahiri sent word back to Khartoum—al-Fadl was never to set foot in Egypt again, even if it was just on a layover. The amounts of money continued to increase. al-Fadl was given $100,000 in a bag of hundred-dollar bills to carry from Sudan to Jordan. He routinely carried or escorted five and six figure amounts of cash to jihadists around the world. His duties were expanded to include many al Qaeda financing operations. As part of this expansion, al-Fadl—still supporting his family on a $6,000 annual salary—was given access to the millionaire bin Laden's bank accounts. The temptation, finally, was too much for him to bear. He began to steal from Osama bin Laden.

the worldwide jihad al-Fadl's discontent continued to grow, even as his responsibilities and knowledge of al Qaeda's operations increased. Mamdouh Salim and Mohamed Loay Bayazid occasionally took al-Fadl to a Sudanese military installation where al Qaeda was participating in a project to convert conventional weapons into chemical weapons. On another occasions, he helped move crates of explosives to Yemen on an al Qaeda boat. There were countless other such transactions.

al-Fadl's discontent continued to grow, even as his responsibilities and knowledge of al Qaeda's operations increased. Mamdouh Salim and Mohamed Loay Bayazid occasionally took al-Fadl to a Sudanese military installation where al Qaeda was participating in a project to convert conventional weapons into chemical weapons. On another occasions, he helped move crates of explosives to Yemen on an al Qaeda boat. There were countless other such transactions. al-Fadl met a wide swath of humanity while working for al Qaeda. The network's members and employees came from all over the world, from virtually every race and nationality. One member even had Israeli citizenship. The list of countries where al Qaeda had significant members and operations underway was nothing short of staggering—from Yemen to Italy to Pakistan, Nigeria, France, Chechnya, Germany, Oman, Great Britain, Bosnia, and Canada, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, the Philippines, Tajikstan... even from the United States. Especially from the United States. Other terrorist groups worked with al Qaeda in many of these countries; some of the groups had collectively made the bayat oath. Although the Western media sometimes portrays al Qaeda as a group of random killers, al-Fadl described a group with a keen focus. The bulk of the aforementioned operations were explicitly devoted to overthrowing existing governments and replacing them with Islamic governments. In a few countries so Westernized that this goal was impracticable, al Qaeda simply intended to hurt existing governments and keep on hurting them until they became so demoralized that they removed themselves from those regions al Qaeda deemed to be Muslim lands.

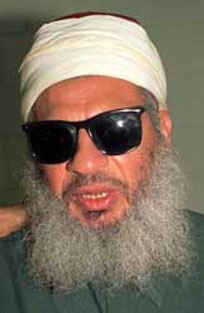

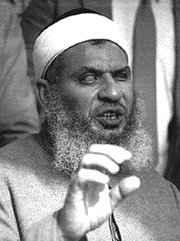

Rahman had taken over Brooklyn's Farouq mosque in 1991—after the brutal murder of al-Fadl's former imam, Mustafa Shalabi, the man who started him on the path to al Qaeda. Shalabi had deep ties within the community, and the situation was delicate. al Qaeda quietly sent al-Fadl's nemesis—Wadih el-Hage—to take charge of the transition from Shalabi to Rahman. Conveniently, el-Hage arrived in town just a few hours before Shalabi was murdered. If al-Fadl had suspicions about who had killed his old mentor, he kept them to himself. The murder has never been solved, but its most immediate consquence was to firmly align al-Farouq with al Qaeda, in both ideology and operation. With Rahman ensconced in the al-Farouq mosque, al Qaeda was now in a position to take its jihad to the United States.

nuclear aspirations As Rahman's followers began to lay plans for a terrorist attack on U.S. soil, Jamal al-Fadl was diving ever deeper into al Qaeda's terrorist agenda. Toward the end of 1993, the head of al Qaeda's financial committee called al-Fadl with a new assignment, his biggest to date.

As Rahman's followers began to lay plans for a terrorist attack on U.S. soil, Jamal al-Fadl was diving ever deeper into al Qaeda's terrorist agenda. Toward the end of 1993, the head of al Qaeda's financial committee called al-Fadl with a new assignment, his biggest to date. "He told me we hear somebody in Khartoum, he got uranium, and we need you to go and study that, is that true or not," al-Fadl said. The seller was a former president of the Sudan and the asking price was $1.5 million, plus commission for two of the middlemen. al-Fadl investigated the claim and set up a meeting. Bayazid was brought in to oversee the operation, along with Abu Musab al Suri, a red-headed expert in weapons of mass destruction who had become a member of the Shura Council. Returning to al-Fadl, Bayazid rattled off a list of criteria the uranium would have to meet before the purchase could proceed. The questions were detailed and knowledgeable. This was no idle dalliance; it was only one phase in an ongoing campaign to obtain weapons of mass destruction. Bayazid attended the next meeting with the seller's representatives. After switching cars, the small group traveled to a house, where the sellers brought out a cylinder two to three feet tall, engraved with technical information, which Bayazid examined. "OK, that's good," he told al-Fadl.

When they returned to al Qaeda's offices, Bayazid filled out what appeared to be al-Fadl had another meeting with an officer named Mobruk, another representative of the seller. Mobruk told al-Fadl he wanted to deal directly with Bayazid from now on. According to al-Fadl, Mobruk gave him $10,000 (more than his yearly salary) and thanked him for a job well done. After this exchange, al-Fadl said, he was not involved in any further activity regarding the uranium purchase. He said he didn't know if it was ever completed. The account doesn't add up, of course. If the purchase did not proceed, why was al-Fadl given a $10,000 payment? Was it a middleman commission, or was it intended for al Qaeda's coffers, just one in a number of thefts by the ever-more resentful, low-wage terrorist worker? U.S. authorities later captured or questioned most of the al Qaeda operatives involved in the uranium deal. It is believed that the sale was never completed, but unanswered questions remain.

terror in new york In 1993, jihad arrived in America—in the form of a truck bomb planted beneath the World Trade Center.

In 1993, jihad arrived in America—in the form of a truck bomb planted beneath the World Trade Center.With Rahman's guidance, a group of terrorists from various backgrounds had coalesced into two separate, but closely linked, cells. The first cell struck in February, when it executed the Trade Center bombing under the operational control of Ramzi Yousef, whom al-Fadl had met during his early training in Afghanistan. A few months later, the second cell prepared to strike, but its' planned Day of Terror was foiled by the FBI, which had placed an informant in the group. The plotters were arrested, and Rahman was arrested as their leader.

An emergency meeting was called when news of Rahman's arrest arrived in al Qaeda's Sudan headquarters, but no action came of it. Some al Qaeda members resigned in protest. Others simply took action under the auspices of affiliated groups. Bin Laden promised that something would be done, but not until later. Al Qaeda remained focused on its primary goal. Disillusioned, resentful and less than wealthy, Jamal al-Fadl had become a parasite on al Qaeda's terrorist operations. During his time in the Sudan, al-Fadl handled some of al Qaeda's legitimate business transactions, such as purchases of sugar and oil, which bin Laden's businesses then resold at a profit to the Sudanese. Al-Fadl began skimming "commissions" off the purchases, which were funded by a combination of al Qaeda and bin Laden's personal bank accounts. Eventually, his "commissions" totaled more than $110,000, according to al-Fadl—probably a low-end estimate. He used the money to buy real estate for his sister and himself, and he bought a car.

The officials were appalled. He was one of al Qaeda's original members; such a betrayal was inconceivable. Al-Fadl apologized and offered to try to repay the money. They asked why. Osama bin Laden, they told him, wanted to know why. al-Fadl launched into a tirade. Others had done what he did, he claimed. The Egyptians had done it. The Egyptians got the best of everything. They got higher salaries than al-Fadl. Everyone got higher salaries than al-Fadl! And he was a senior member! Who deserved it more than he? The financial committee was not impressed. This is no reason to steal, they told him. It was agreed he would pay back the money. Al-Fadl produced about $30,000, but he said he couldn't get any more. Not good enough, the head of the financial committee told him. If he paid back half, they would consider letting him pay the rest in installments. Any alternative to this proposal would have to be approved by bin Laden.

"I don't care about the money, but I care about you, because you have been with us from the beginning. You worked hard in Afghanistan, you are one of the best people in al Qaeda," bin Laden said (as al-Fadl related the story). "We want to know... We give you a salary, we give you everything. When you travel we give you extra money. We pay your medical bills. Why you did that? What did you need the money for? Did someone outside of al Qaeda put you up to it?" Al-Fadl repeated his complaints about the Egyptians, and he repeated his complaints about the inequities in salary. People with less seniority made more than he did! It wasn't fair! Bin Laden was the picture of wounded sincerity, as al-Fadl remembered it. "There's no reason for you to do that. If you need money, you should come to us," he responded. "You should come speak with me, and tell me 'I want to buy a house. I want to change my car.' And you didn't do that. You just stole the money." Al-Fadl did not say whether a tiny tear of sorrow and betrayal appeared in the corner of the global terrorist chief's eye, but one can easily imagine it. "I ask you to forgive," al-Fadl said. "I want to be part of al Qaeda again. I want to continue." "There's no forgiveness until you bring all the money back. I cannot do that," bin Laden said. "If I say OK, that means everybody else in al Qaeda will accept your reason for taking the money. Go do your best, and give all the money back. And after that, everything will be fine. " "But there's no money left," al-Fadl said. "I can't forgive you until you give back all the money," bin Laden replied. That was the end of the meeting.

escape from al qaeda al-Fadl was filled with despair. He tried to plead with the financial chairman, but he got only the same response—"You have to bring the money back, and after that everything is going to be fine." But al-Fadl didn't have the money, and he wasn't willing to give up the money he did have. In February 1995, he decided to flee, leaving his wife and family behind.

al-Fadl was filled with despair. He tried to plead with the financial chairman, but he got only the same response—"You have to bring the money back, and after that everything is going to be fine." But al-Fadl didn't have the money, and he wasn't willing to give up the money he did have. In February 1995, he decided to flee, leaving his wife and family behind. Al-Fadl's escape took him through several countries as he searched for someone to help him. He went to Syria, where he asked for help from the United Nations. They gave him some money to live, but little else. From there, he went to Jordan, where he asked an al Qaeda member he knew there to help him resolve the dispute. This too yielded little result. He tried to go to Israel, on the theory that the Israelis hated the Sudanese National Islamic Front enough to help him, but he never made it across the border. In Lebanon, he tried to sell a book about the NIF, but the publisher was too greedy. Seven years earlier, al-Fadl had devoted his whole life to the cause of jihad. Now, his only cause was money.

There, al-Fadl tried to win support for opposing bin Laden, who by this time had fallen out of favor with his home government. He was received by senior members of the Saudi intelligence, who were politely disinterested in the NIF. Instead, they cheerfully suggested he assassinate bin Laden. Al-Fadl cheerfully replied that he would be happy to undertake the task with the assistance of relatives back in the Sudan. But the Saudis didn't offer any cash up front, and he soon became disillusioned. In the summer of 1996, the Saudis sent him back to Eritrea and told him to sit tight, then report to their embassy there. He didn't like the plan they had proposed, which would have him traveling back to Pakistan at great personal risk. Even worse, he began to suspect that the Saudis would give most of their money to his Sudanese relatives and cut him out of the loop. Despairing of the ever-elusive paycheck, al-Fadl finally set his sails toward his berth of last resort. Al Qaeda's greatest enemy was the United States. Surely, the Americans would protect him. "I went to the American embassy [in Eritrea], and I went to the visa line," he said. When he had waited his turn, he told the man behind the counter, "I have some information for your government, and if your government help me. I have information about people. They want to do something against your government." He was asked to take a seat. After 20 minutes, a woman escorted him into a back office and asked what sort of information he was offering. "I was in Afghanistan, and I worked with a group," he told her. "And I know those people, they are trying to make war against your country."

The woman behind the desk told him to come back Wednesday. When he did, she had a battery of more specific questions for him. After he answered them all, she asked him to come back Friday. There were U.S. intelligence agents waiting for him, with more questions. The conversations continued for days. Al-Fadl answered many of their questions, but he didn't tell them he had stolen from al Qaeda. They pressed him, saying that they knew about something he had done in the Sudan, and finally he confessed. He gave them hundreds of names of people linked to al Qaeda. Some they asked about and others he volunteered. After weeks of back and forth, the Americans were satisfied that they had a person of value on their hands. Al-Fadl was shuttled off to Europe. There, U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald and FBI Agent Danny Coleman flew to meet with the man who would soon become their star witness. Al-Fadl was shocked as he continued to meet with these people, enemies of Islam, the people upon whom he had worked to unleash nuclear armageddon. "You know, you really don't have horns in your heads," he told Fitzgerald. After negotiations, al-Fadl agreed to come to the United States with no agreement in place. In a leap of faith, he entrusted himself to the American criminal justice system and agreed to do everything the prosecutors asked of him. In November of 1996, he put his pledge in writing, trusting the system would reward him for the information he offered. The system would not let him down.

the trial Al-Fadl pleaded guilty to multiple counts of conspiracy against the United States, with a maximum sentence of 15 years. He didn't have a firm agreement regarding his sentence, but sentencing was deferred while he cooperated with officials in their investigation of al Qaeda.

Al-Fadl pleaded guilty to multiple counts of conspiracy against the United States, with a maximum sentence of 15 years. He didn't have a firm agreement regarding his sentence, but sentencing was deferred while he cooperated with officials in their investigation of al Qaeda. For nearly two years, al-Fadl was kept in custody by the FBI, which watched him 24 hours a day. Eventually, he was moved into the Witness Protection program. The government arranged to have al-Fadl's Sudanese family flown to the U.S. to join him in hiding. They covered his living expenses and those of his family. The bills for al-Fadl's upkeep would eventually extend into hundreds of thousands of dollars—with no end in sight. Despite all this activity and cost, nothing happened for months on end. Al-Fadl talked and the government listened. Prosecutors had a witness, but no case in which he could testify. al Qaeda obliged them.

Salim and Ali Mohamed had their cases broken away from the primary case, which would bear the fateful name US v. Usama bin Laden. Salim's case was separated after the aforementioned eye-stabbing incident. Ali Mohamed's case was handled separately because, well, you really have to read it to believe it. Jamal al-Fadl had finally hit the jackpot. He could get his revenge on the overpaid Egyptians, and get paid to do it. al-Fadl came out on the second day of the trial and stayed for several days, telling his long and convoluted story. His role as a witness was sometimes questionable—between his admitted love for money, the government's humongous bills for supporting him and his family, and the sometimes fuzzy nature of his recollectons. However, he did better than the other al Qaeda informant who testified during the trial that when he identified el-Hage to an interrogator as an al Qaeda member, "I did not tell him the entire truth. My aim was to have him get me out of my jail cell." Inconsistencies or no, el-Hage and the other three defendants were convicted and sentenced to life in prison on a variety of charges. Three were convicted on murder charges; el-Hage was convicted only on conspiracy, since no one ever connected him to the bombings proper. Al-Fadl had done his duty. Now he awaited his reward. Would his sentence be zero years or 15?

Then, of course, everything changed. al-Fadl was in the catbird seat. Just a couple months earlier, al-Fadl had been a small fish playing a vital role in a complicated case that had already been largely forgotten. He was also a felon—having entered a guilty plea to conspiracy to injure and destroy national defense material, premises and facilities of the United States, and conspiracy to carry an explosive during the commission of a felony. His sentence was supposed to be somewhere between zero and 15 years, depending on how useful he made himself. al-Fadl being al-Fadl, he somehow managed to negotiate a $20,000 "loan" from the U.S. government on top of the sentencing deal.

On September 12, Jama al-Fadl was suddenly a national treasure. His sentencing was simply forgotten, apparently permanently. Although he had been "arrested" when he surrendered to the U.S., he was never imprisoned, despite six years as Osama bin Laden's right-hand man. His services were too much in demand. In addition to new visitors from intelligence agencies and the military, there were new cases in which his testimony was sought, such as the government's prosecution of the president of the Benevolence International Foundation. (Al-Fadl's star turn was aborted by a plea deal at the last minute.) To this day, al-Fadl has never seen the inside of a jail cell, and there's a good chance he never will. The value of his testimony to the historical record is significant, but there is a serious question whether his value to prosecutors justifies the substantial cost of his upkeep. At the end of 2005, al-Fadl's greatest achievement—the conviction of el-Hage and three others for the African embassy bombings—teetered on the verge of falling apart when it was revealed that the U.S. Marshals Service (administrators of the Witness Protection program) had withheld hours of videotapes recording al-Fadl's conversations with FBI agents.

The presiding judge in the case denied el-Hage's bid for a new trial, but in a harshly worded ruling, he savaged the Marshals for "a mixture of inaction, incompetence and stonewalling" and an attempted "cover-up," while urging the defendant to appeal, which he has since done. An overturned conviction would not mark a glorious note on which to end al-Fadl's career, but then he wasn't exactly a glorious guy. The pot-head turned terrorist turned terrorist-paper-pusher turned embezzler turned snitch is most likely destined to live out his days churning up increasingly inane bits of trivia to keep the dogs at bay, until, at last, he wears out his welcome or bankrupts the Witness Protection program. A swift deportation followed by a drive-by shooting will most likely follow, although he could alternatively end up in a secret prison at an undisclosed location. Either way, he isn't making his mother proud. |

To this day, al-Fadl's story is best available public account of the origins of al Qaeda, and the most detailed description of how the group transforms aimless young men into bloodthirsty holy warriors.

To this day, al-Fadl's story is best available public account of the origins of al Qaeda, and the most detailed description of how the group transforms aimless young men into bloodthirsty holy warriors.  The Kingdom was the wrong place for alternative lifestyles. Jamal and Ted's excellent adventure came to an end when al-Fald's roommate was busted for possession (two years in prison, but he apparently escaped flogging). al-Fadl hit the road, looking for a land more friendly to

The Kingdom was the wrong place for alternative lifestyles. Jamal and Ted's excellent adventure came to an end when al-Fald's roommate was busted for possession (two years in prison, but he apparently escaped flogging). al-Fadl hit the road, looking for a land more friendly to  Like many

Like many  At guesthouses, the recruits gathered to absorb the inspirational preaching of Osama bin Laden and other eminent theologians, such as Mamdouh Salim, who would later distinguish himself by throwing pepper sauce into the eyes of an American prison guard, then gouge out one of the same eyes with the sharpened tip of a comb.

At guesthouses, the recruits gathered to absorb the inspirational preaching of Osama bin Laden and other eminent theologians, such as Mamdouh Salim, who would later distinguish himself by throwing pepper sauce into the eyes of an American prison guard, then gouge out one of the same eyes with the sharpened tip of a comb.  The Shura Council included Zawahiri, bin Laden, Sheikh Sayyid el Masry, Dr. Fadhl el Masry, Abu Musab al Suri, and a number of people known to al-Fadl only by aliases.

The Shura Council included Zawahiri, bin Laden, Sheikh Sayyid el Masry, Dr. Fadhl el Masry, Abu Musab al Suri, and a number of people known to al-Fadl only by aliases.  Again invoking cult-like techniques, the bayat vow required extraordinary commitment from followers. If a follower was told to go anywhere in the world, or cooperate with any other group, he was obliged to obey—even if the order was haram, forbidden under normal circumstances by Islamic law. In this, al Qaeda's leaders were following a tradition that dated back to

Again invoking cult-like techniques, the bayat vow required extraordinary commitment from followers. If a follower was told to go anywhere in the world, or cooperate with any other group, he was obliged to obey—even if the order was haram, forbidden under normal circumstances by Islamic law. In this, al Qaeda's leaders were following a tradition that dated back to  After the withdrawal of the Soviets, Afghanistan had devolved into a series of battles between various factions, each of whom saw themselves as the rightful rulers of the land. While things were getting bogged down there, the government of Sudan came under the control of Islamic fundamentalists.

After the withdrawal of the Soviets, Afghanistan had devolved into a series of battles between various factions, each of whom saw themselves as the rightful rulers of the land. While things were getting bogged down there, the government of Sudan came under the control of Islamic fundamentalists.  Like any other multinational corporation, al Qaeda had an office suite. Osama Bin Laden had the corner office, of course. Based out of Khartoum, al Qaeda's headquarters operation employed receptionists, secretaries, accountants and bureacrats. Subsidiary companies had their own CEOs.

Like any other multinational corporation, al Qaeda had an office suite. Osama Bin Laden had the corner office, of course. Based out of Khartoum, al Qaeda's headquarters operation employed receptionists, secretaries, accountants and bureacrats. Subsidiary companies had their own CEOs.  Lubani—whose real name was Wadih el-Hage—was an American citizen and one of bin Laden's most trusted aides. If al-Fadl especially resented el-Hage, he didn't let on. By the end, al-Fadl would have the last laugh. His revenge on el-Hage would exceed the wildest dreams of even the most resentful corporate drones.

Lubani—whose real name was Wadih el-Hage—was an American citizen and one of bin Laden's most trusted aides. If al-Fadl especially resented el-Hage, he didn't let on. By the end, al-Fadl would have the last laugh. His revenge on el-Hage would exceed the wildest dreams of even the most resentful corporate drones.  Although he had been put on standby, al-Fadl he never went to Somalia himself (or so he later claimed when staring down the barrel of a criminal prosecution). He knew other people who had. Abu Talha al-Sudani came to al-Fadl on his return from Somalia, flush with cash, and asked al-Fadl to help him buy a house with the bonus money he had been paid by al Qaeda.

Although he had been put on standby, al-Fadl he never went to Somalia himself (or so he later claimed when staring down the barrel of a criminal prosecution). He knew other people who had. Abu Talha al-Sudani came to al-Fadl on his return from Somalia, flush with cash, and asked al-Fadl to help him buy a house with the bonus money he had been paid by al Qaeda. To accomplish these stratospheric ambitions, al Qaeda collaborated with other groups all over the world. One such partner was the Islamic Group, an Egyptian jihadist organization headed by blind sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, an ally of bin Laden and Zawahiri, who had recently taken up residence in al-Fadl's old stomping grounds.

To accomplish these stratospheric ambitions, al Qaeda collaborated with other groups all over the world. One such partner was the Islamic Group, an Egyptian jihadist organization headed by blind sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman, an ally of bin Laden and Zawahiri, who had recently taken up residence in al-Fadl's old stomping grounds.  a requisition, which al-Fadl took to Mamdouh Salim for approval. Once Salim signed off on the request, al-Fadl set up another meeting with the seller's representative, a man named Basheer. The deal was on, but Bayazid and Abu Musab wanted to test the uranium using a machine they would import from Kenya.

a requisition, which al-Fadl took to Mamdouh Salim for approval. Once Salim signed off on the request, al-Fadl set up another meeting with the seller's representative, a man named Basheer. The deal was on, but Bayazid and Abu Musab wanted to test the uranium using a machine they would import from Kenya.  al Qaeda had provided support for both plots. As part of Rahman's trial, prosecutors released a long list of unindicted co-conspirators—including Osama bin Laden, his brother-in-law

al Qaeda had provided support for both plots. As part of Rahman's trial, prosecutors released a long list of unindicted co-conspirators—including Osama bin Laden, his brother-in-law  When his customers started complaining to headquarters that al-Fadl was charging commissions on al Qaeda transactions, officials from the financial committee confronted him with the allegations. He denied them, but then the charges were repeated by other customers, trusted customers. Al-Fadl was called into the office again. Caught, he finally confessed his crime.

When his customers started complaining to headquarters that al-Fadl was charging commissions on al Qaeda transactions, officials from the financial committee confronted him with the allegations. He denied them, but then the charges were repeated by other customers, trusted customers. Al-Fadl was called into the office again. Caught, he finally confessed his crime.  Although al-Fadl still owned most of the properties he had bought using bin Laden's money, he continued to insist that repayment was impossible. Al-Fadl asked the financier to set up the meeting, and it was arranged for the following week.

Although al-Fadl still owned most of the properties he had bought using bin Laden's money, he continued to insist that repayment was impossible. Al-Fadl asked the financier to set up the meeting, and it was arranged for the following week.  Al-Fadl landed in Eritrea and repeated the routine. This time, he approached the local al Qaeda affiliate and tried, fruitlessly, to interest them in funding a Sudanese opposition group. When they passed, he went where the real money was—Saudi Arabia.

Al-Fadl landed in Eritrea and repeated the routine. This time, he approached the local al Qaeda affiliate and tried, fruitlessly, to interest them in funding a Sudanese opposition group. When they passed, he went where the real money was—Saudi Arabia. Al-Fadl's warning, rendered in halting English, was prophetic nevertheless. "Maybe they try to do something inside United States, and they try to fight the United States Army outside, and also they try make bomb against some embassy outside."

Al-Fadl's warning, rendered in halting English, was prophetic nevertheless. "Maybe they try to do something inside United States, and they try to fight the United States Army outside, and also they try make bomb against some embassy outside." On Aug. 7, 1998, the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, were attacked with

On Aug. 7, 1998, the U.S. embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, were attacked with  US v bin Laden wasn't even an early contender for trial of the 21st century—not when viewed against such highlights in the history of jurisprudence as the

US v bin Laden wasn't even an early contender for trial of the 21st century—not when viewed against such highlights in the history of jurisprudence as the  And all that was before the

And all that was before the  The chats covered his immigration status, about his inability to find a job, about his prospects for zero jail time—in short, the million and one reasons why he might want to tilt his testimony in the direction prosecutors wanted to go.

The chats covered his immigration status, about his inability to find a job, about his prospects for zero jail time—in short, the million and one reasons why he might want to tilt his testimony in the direction prosecutors wanted to go.