|

al Qaeda as Ecumenical Outreach After September 11, many casual observers sought to draw comparisons between al Qaeda's brand of deadly Islamic fundamentalism and the Assassin cult. But it doesn't take long to identify the big problem with the notion.

After September 11, many casual observers sought to draw comparisons between al Qaeda's brand of deadly Islamic fundamentalism and the Assassin cult. But it doesn't take long to identify the big problem with the notion. al Qaeda is a Sunni Muslim fundamentalist sect; the Assassins were Shi'ites. And when you think about fundamentalists, you usually think about people who too intolerant to work with those who do not share their beliefs. But since the fall of the Soviet Union, a direct result of the Afghanistan jihad, experts have tracked a surprising amount of cooperation among disparate groups of Islamic extremists. They may not like each other, but they can work together when it serves their purposes. The trend began in the late 1970s, when a series of events rocked the Islamic world. For politically minded Muslims of every sect (sometimes referred to as Islamists), 1979 was a year to remember, with three watershed developments that permanently changed the world's political and religious landscape.

The first event created a broad surge of enthusiasm among many Muslims, whether Sunni or Shi'ite. As Washington Post editor Steven Coll noted in Ghost Wars: The Secret History of Afghanistan, the CIA and bin Laden, the Iranian revolution reverberated powerfully among small bands of Sunni militants around the world. Perhaps the most powerful such group at the time was the Muslim Brotherhood, a secret society with the goal of establishing Islamic governments around the world, which many believe was responsible for the 1979 attack on Mecca. Although closely associated with Sunni fundamentalism, the Brotherhood's reach extended into many diverse communities in pursuit of its stated political goal of creating Islamic governments. The third domino was the sum of the first two. Abdullah Azzam, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood and Osama bin Laden's mentor, led a pan-Islamist charge into Afghanistan to repel the Soviets. It was the first step toward creating al Qaeda in the form we know it today. Although the Afghan jihad reached across many sectarian lines, a deeper agenda played out over the course of the conflict.

The Theology of MisdirectionEveryone knows Osama bin Laden wants to kill Americans, but if you asked people on the street, you would find very few who can articulate what bin Laden actually believes.al Qaeda's top leadership is dominated by a few specific fundamentalist influences. The most dominant of these is Al Takfir Wal Hijra, an Arabic phrase meaning "excommunication and exile." The Takfir cult originated as an Egyptian separatist movement. Led by an agricultural specialist named Shukri Ahmed Mustafa, the original Takfiris believed in emulating the Prophet Muhammad's flight from Mecca to live a purified life in the desert. Mustafa and some followers set up a self-sufficient survivalist-style camp in a remote area, where inhabitants lived according to the strictest interpretation of Shariah law. The group was derisively referred to as "the Desert Flogging Group," after their habit of kidnapping and flogging those who didn't live up to their moral standards.

For a while, people thought that was the end of the sect. Unfortunately, they were dead wrong. It's unclear whether the survivors regrouped, or whether the sect reconstituted itself under a different name.The most likely scenario is that it was reconstituted by its original parent group, the Muslim Brotherhood. Although the original Takfiris were concerned with isolating themselves and battling the secular government of Egypt, the cult is believed to have been an offshoot of the Brotherhood, an international movement. Shukri Mustafa was a member of the Brotherhood, once arrested for distributing its literature in Egypt. The Takfiris and the Saudi Wahabbi sects both drew inspiration from the writings of another Muslim Brother, Sayyid Qutb. Qutb was an Egyptian writer who traveled to the United States during the late 1940s. Appalled by American culture, he returned to Egypt, joined the Brotherhood and began outlining a philosophy of jihad. He died a martyr to his cause, executed by the government in 1966. Qutb believed that the world is repeating the events that occurred at the birth of Islam, when Muhammad arrived to redeem Arabia from what Muslims believe was a period of barbarism, great depravity and ignorance of the true God—a condition summed up by the Arabic word jahiliyyah. In Qutb's view, Muhammad's solution was to convert as many as he could and conquer those he could not. Qutb proposed much the same scenario as the solution to the evils of the modern, Western world. Among Qutb's major points are the need to purify a sinful world, and he urged Muslims to avoid living with kuffar (infidels) in order to avoid being contaminated by their lax morals. The most efficient solution to the problem, of course, is to get rid of the kuffar. "This movement uses the methods of preaching and persuasion for reforming ideas and beliefs, and it uses physical power and jihad for abolishing the organizations and authorities of the jahili system which prevents people from reforming their ideas and beliefs," Qutb wrote.

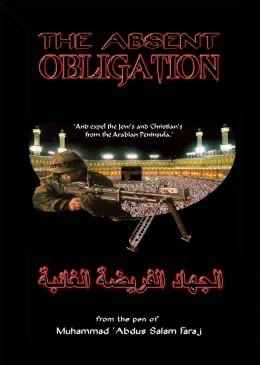

[T]his religion forbids the imposition of its belief by force, as is clear from the [Koranic] verse, 'There is no compulsion in religion,' while on the other hand it tries to annihilate all those political and material powers which stand between people and Islam, which force one people to bow before another people and prevent them from accepting the sovereignty of God. [...] After Qutb, another Egyptian writer helped delineate the boundaries of jihad, or more accurately, he helped eradicate any boundaries to jihad. One of the most influential extremist tracts in the Muslim world, The Neglected Duty by Muhammad Abd al-Salam Faraj was a significant text for the Takfir cult. Printed during that momentous year of 1979, The Neglected Duty (also known as The Absent Obligation) urges Muslims to undertake violent jihad with the ultimate goal of creating the global caliphate. For its justification, Duty turns to a verse in the Koran known as "the verse of the sword": So when the sacred months have passed away, then slay the idolaters wherever you find them, and take them captives and besiege them and lie in wait for them in every ambush, then if they repent and keep up prayer and pay the poor-rate, leave their way free to them; surely Allah is Forgiving, Merciful. Even more significantly, from the perspective of the terrorist, Faraj—yet another former member of the Muslim Brotherhood—endorsed the use of any means necessary to advance the cause of jihad. The sword was not the only Assassin's art he endorsed. A paper titled Apocalypse 9/11, written by John R. Hall and published online by the University of California, Davis's Center for History, Society, and Culture, describes the broad exemptions outlined by Faraj: Faraj insisted that jihad is not subject to codified Islamic legal restraints-for example, prohibiting the killing of non-combatants-and that it does not require a fatwa, or religious ruling affirming approval by Muslim authorities. Moreover, for Faraj, according to sociologist Charles Seligman, jihad is no longer simply a series of battles between soldiers; it can draw on "deception and deceit, surprise attacks, trickery and large scale violence." Farah also redefined taqiyya, an Arabic word for theologically justified deception in Islam. Among moderates, taqiyya is the act of pretending to be non-Muslim in order to avoid persecution. Moderate Muslims have a very narrow view of circumstances under which it is acceptable to practice taqiyya.

Takfiri cells are trained to blend into Western societies, which they view as "kufar" (atheist, corrupt, or infidel) in order to plot terrorist attacks against those "corrupt" societies. Members of Takfiri cells may live together, not pray or attend Mosque, partake in alcohol and narcotics, and dress to assimilate and integrate into the communities they live in an attempt to avoid suspicion and/or detection. Using these tactics, the Takfiris expanded out of Egypt and across the Middle East, Europe and Africa. They are known or suspected to operate actively in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sudan, Lebanon and Algeria. Much like the fidais of the Assassins, Takfiri agents have infiltrated in Germany and the U.K. Al-Zawahiri, the sect's best known member, traveled to the United States and Australia to raise funds and seek recruits during the 1990s, with assistance from sleeper operatives in the host countries. According to Time Magazine, Takfiri recruits were sent to train in the Afghanistan indoctrination camps, where they were inducted into al Qaeda and further trained in Takfiri ideology.

By the time al-Qaeda had resettled in Afghanistan, ideological training was an integral part of the curriculum, according to a (Middle Eastern) recruit who went on to bomb the U.S. embassy in Nairobi. Students were asked to learn all about demolition, artillery and light-weapon use, but they were also expected to be familiar with the fatwas of al-Qaeda, including those that called for violence against Muslim rulers who contradicted Islam-a basic Takfiri tenet. French terrorism expert Jacquard describes Takfiri indoctrination this way: "Takfir is like a sect: once you're in, you never get out. The Takfir rely on brainwashing and an extreme regime of discipline to weed out the weak links and ensure loyalty and obedience from those taken as members." The result of all this was to subtly shift the dynamic of the political Muslim community. Abdullah Azzam, who led the jihad against the Soviet Union until his assassination in 1989, was a "pan-Islamist," running what seemed to be a broadly inclusive campaign. Azzam went to Afghanistan and united the disparate Islamic constituency there by appealing to Muslim identity over and above the many tribal and sectarian splits. The same appeal was used to summon a flood of Muslims from around the region as holy warriors. bin Laden has used similar appeals, issuing statements under broadly inclusive language. In a 1998 statement on behalf of a coalition of terrorist groups called the World Islamic Front, bin Laden ruled that it is the obligation of Muslims everywhere to kill Americans, quoting the Koran in urging Muslims to "fight the pagans all together as they fight you all together." But once the volunteer fighters arrived in Afghanistan, the definition of "all together" became more clear. Recruits were indoctrinated at training camps into a secret society, using a system of initiated degrees similar to the structure employed by the Assassins a millennium earlier (see Mind Control And Murder Cults). This organization is the core al Qaeda network. Using a strategy of outward inclusiveness, the Takfiri seized an opportunity to indoctrinate new recruits with its ideology.

Modus OperandiThe use of such subterfuge under the guise of Islamic unification is not new. Like the Takfiris, The Assassins used deceptive tactics to recruit new members, as well as to protect themselves in times of danger and forge alliances across sectarian lines.Both sects have both used the principle of taqiyya—religiously sanctioned deception—to assimilate and cooperate with other Muslims—for as long as it suits their purposes. Like the Takfiris, the Assassins had always practiced taqiyya as part of infiltrating hostile cultures. But at one point, the entire sect underwent a radical change of outer religious practice in order to integrate with the politically dominant Sunni empire that surrounded them.

Declaring himself Caliph, the divinely appointed leader of Islam, Hassan demanded that they turn their backs to Mecca when they prayed, then led them in a debauch of wine, pork and orgies. He even ordered those who clung to the Shariah to be stoned as blasphemers. Not surprisingly, this development did not endear the Assassins to the mainstream Muslim community, and they were branded as heretics. The tension between the Nizaris and mainstream Muslims in the region continued for almost 50 years, until the reign of Hassan III. Hassan III didn't just take the Assassins back to its Shi'ite origins; he constructed a rapprochement with the Sunni caliphate, the dominant political force in the region. While outwardly embracing Shariah, the Assassins maintained the inward radicalism of the sect with a complex theological argument for "occultation," according to James Wasserman, author of The Templars and the Assassins, The Militia of Heaven. A variation on taqiyya, the doctrine called for the outward practice of Shariah as a transitional period before the final emergence of the Mahdi (messiah). As a result, the Assassins forged peace with the Sunni empire, and even accepted the authority of the Sunni Caliph, who allowed his court to intermarry with the Nizaris. But the core beliefs of the sect endured until their final military defeat in the mid-13th century, and beyond, when the group broke up into small scattered communities and dispersed around the world. The occultation doctrine was not widely known at the time, of course, or else the Sunnis would not have accepted the Nizari efforts at reconciliation. There is no information about the Takfiris attitude on the subject either, but al Qaeda has frequently presented an ecumenical call that belies its fundamentalist roots. The result is a seemingly paradoxical pattern. Although establishment fundamentalists such as the Wahabbis decry the Shi'ites as apostates, the core al Qaeda group has called for Muslim unity at the same time that its affiliates attack Shi'ite mosques. al Qaeda has frequently worked with Shi'ite regimes and organizations, including the government of Iran and terror groups like Hezbollah. It isn't known how deep these ties run, but the evidence suggests that the relationship is at least comfortable. Even Abu Musab al-Zarqawi—one of the most strident anti-Shi'ites—has reportedly been sheltered by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, along with other top al Qaeda military commanders. On its surface, the relationship is inherently duplicitous on both sides, perhaps appropriate for Iran, the homeland of the Assassins. "The Iranians play a double game. Everything they can do to trouble the Americans, without going too far, they do it," a French official recently told the L.A. Times. "They have arrested important al Qaeda, but they have permitted other important al Qaeda people to operate. It is a classic Iranian style of ambiguity, deception, manipulation." It's a classic al Qaeda style of operation as well, and the approach was practically invented by the Assassins. But these rough parallels between the beliefs and practices of the Assassins and al Qaeda are simply that—parallel lines that never meet—unless some historical track can show where and how those lines might converge. To search for that possible convergence, we must trace al Qaeda's practice of taqiyya back to the terror network's origins, to the original secret society that shaped virtually every aspect of Osama bin Laden's terror network—the Muslim Brotherhood. Next: Then And Now: The Missing Link

|

As a local operation, Takfir Wal Hijra was something of a bust. It quickly came into conflict with Egypt's secular leadership (which represented everything the sect hated) and adopted the methods of terrorism, including kidnapping, firebombing and intimidation. Mustafa, known as the sect's "Commander of the Faithful," was hung in 1978 after the sect kidnapped and executed an Egyptian government official.

As a local operation, Takfir Wal Hijra was something of a bust. It quickly came into conflict with Egypt's secular leadership (which represented everything the sect hated) and adopted the methods of terrorism, including kidnapping, firebombing and intimidation. Mustafa, known as the sect's "Commander of the Faithful," was hung in 1978 after the sect kidnapped and executed an Egyptian government official.  Qutb became the theological voice of the Muslim Brotherhood, and his writings strongly influenced the Takfiris as well as the Wahabbis, the fundamentalist sect that dominates Saudi Arabia. His writings were not subtle in their intent:

Qutb became the theological voice of the Muslim Brotherhood, and his writings strongly influenced the Takfiris as well as the Wahabbis, the fundamentalist sect that dominates Saudi Arabia. His writings were not subtle in their intent:

Faraj expanded the concept to include taqiyya and terrorism, hand-in-hand, as weapons for jihad. While the strategy pervades al Qaeda and may cross sectarian lines, taqiyya and terrorism are particularly employed by the reconstituted Takfiri cult. According to a 2002 U.S. indictment:

Faraj expanded the concept to include taqiyya and terrorism, hand-in-hand, as weapons for jihad. While the strategy pervades al Qaeda and may cross sectarian lines, taqiyya and terrorism are particularly employed by the reconstituted Takfiri cult. According to a 2002 U.S. indictment:

In 1164, Hassan II (descendant of the sect's founder, Hassan I-Sabbah) declared the coming of the Millennium, known as the Qiyama. According to Hassan, the absolute leader of the Nizaris, the end of the world was at hand. During Ramadan, a monthlong period of fasting and contemplation, Hassan told his followers that they had been freed from the constraints of Islamic law, the Shariah.

In 1164, Hassan II (descendant of the sect's founder, Hassan I-Sabbah) declared the coming of the Millennium, known as the Qiyama. According to Hassan, the absolute leader of the Nizaris, the end of the world was at hand. During Ramadan, a monthlong period of fasting and contemplation, Hassan told his followers that they had been freed from the constraints of Islamic law, the Shariah.