|

Abu Faraj al-Libyaka Dr. Taufeek Help wanted: Top terrorist network seeks operational planner. Must have eye for detail, strong work ethic and a thirst for blood. Five to ten years experience, Afghan war a plus. Resemblance to Michael Jackson a plus. Requires masters degree. Salary commensurate with experience. Not an equal opportunity employer.

Help wanted: Top terrorist network seeks operational planner. Must have eye for detail, strong work ethic and a thirst for blood. Five to ten years experience, Afghan war a plus. Resemblance to Michael Jackson a plus. Requires masters degree. Salary commensurate with experience. Not an equal opportunity employer.When the government of Pakistan arrested al Qaeda's top military mind, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, it created a void. After all, the media needs someone to describe as the "mastermind" of any given terrorist attack, whatever that's supposed to mean. Like Richard M. Nixon, Khalid Shaikh was a hard act to follow. Abu Faraj al-Liby could be therefore be considered the Gerald Ford of international terrorism—although his reign was short and undistinguished, there is a certain historical cachet that comes with simply having the job. Born in Libya, Faraj was KSM's protege. He helped Khalid organize the September 11 attack, in some unknown capacity, perhaps fetching coffee and making Xeroxes. Before his arrest, Faraj's most famous characteristic was a bad case of vitiglio, the skin disease that allegedly transformed Michael Jackson from a black man into an almost-white man. It's not every al Qaeda kingpin who can claim solidarity with the Wacko Jacko, the King of Pop.

Most of the Libyan's known exploits were based in Southeast Asia and Northern Africa, where he served as al Qaeda's regional commander. North Africa isn't a bad job to have on your terrorist resume. During his tour of duty, Faraj saw years of extensive infrastructure-building and the execution of a few high-profile attacks on U.S. interests in Somalia and in Tanzania and Kenya. He once served as an assistant to Osama bin Laden, probably while al Qaeda was based in the Sudan during the early 1990s.

After assuming military command of al Qaeda, Faraj hung his hat in Pakistan. His extended visit to the country was a violent one, but he worked to make the country into a more hospitable environment with such political initiatives as his repeated attempts to assassinate Pakistan's president Pervez Musharraf.

Faraj hid out along the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan, where tribal chiefs are the only effective legal authority and the Pakistani military has trouble operating. Al Qaeda's most prominent leaders, bin Laden and Ayman Al-Zawahiri, are also suspected of operating in the region, although the direct evidence for this contention is remarkably slim. The U.S. botched a golden opportunity to collect intelligence on Faraj during the summer of 2004, when a leak exposed a double agent who had been in contact with the Libyan while working for the CIA. Muhammad Naeem Noor Khan was an al Qaeda computer systems expert, who coordinated operations via e-mail from his home base in Karachi, Pakistan. Khan took messages verbally and in writing from top al Qaeda leaders along the Pakistan-Afghanistan border, then encrypted and e-mailed them. Khan processed message traffic for the elite of al Qaeda, including bin Laden, Zawahiri and Faraj, until a story in the New York Times trumpeted his arrest and blew Khan's cover, ending the fruitful operation. Despite this mishap, the Pakistanis finally caught up with Faraj in the spring of 2005—or so the story goes. The Pakistanis announced the arrest rather gleefully, prompting an effusive bout of praise from the Bush Administration—yet another X through the picture of a "senior al Qaeda leader" racked up on the scorecard GW keeps in his desk drawer. Except that the arrest may not have been what it seemed. About a week after the trimphant announcement, rumors began to spread (starting with a report in the Times of London) that the captured al Qaeda operative had been Anas al-Liby, one of the planners of the 1998 African embassy bombings, and not Faraj al-Liby. Both men were, after all, from Libya, and all Libyans look alike. Like Faraj, Anas al-Liby also has a disfigured face, but there's a big difference between having a scar and having vitiglio. After a year of silence on this topic, it appears likely Faraj was actually the guy the Pakistanis apprehended, but then the recriminations about his importance began. Was he al Qaeda's No. 3 commander, as officials claimed? (Probably not. It's not even clear al Qaeda [[mind control and murder cults|works that way].) The Times quoted a bin Laden associate as saying Faraj used to "he used to make the coffee and do the photocopying." It wasn't clear whether Faraj or Anas was the No. 3 guy, if there was a No. 3 guy, or whether one of the half-dozen other guys labeled "al Qaeda's No. 3" might be the actual No. 3, if there ever was such a thing. Regardless of whether Faraj was enriching uranium or straining grounds out of the coffee pot, he appears to be out of the loop now. Fortunately, there is an apparently unending supply of "senior al Qaeda leaders" to fill the gap when one drops out. Pakistan wanted to keep al-Liby for trial, what with the assassination attempts and everything, but they caved and turned him over to the U.S. in June 2005, which promptly deposited him in secret CIA prison in an undisclosed location. Needless to say, Faraj al-Liby will never be seen again if the Bush Administration has its way. But "never" is just another word for 2009, when a new president will step in and presumably try to pick up whatever shattered pieces of the Constitution haven't been already been ground into dust.

|

As far as the West was concerned, Faraj barely existed until 2003, when a series of suspects were arrested around the world, and all of them appeared to be taking orders from the same guy.

As far as the West was concerned, Faraj barely existed until 2003, when a series of suspects were arrested around the world, and all of them appeared to be taking orders from the same guy.  At some point, Faraj became a deputy to KSM. His contacts stretched around the world, including

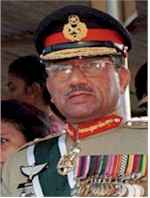

At some point, Faraj became a deputy to KSM. His contacts stretched around the world, including  Musharraf, a virtual dictator who seized power through a military coup, is not an ideal leader by American standards, but he's better than some of the alternatives (and worse than many others). A successful assassination could plunge Pakistan into a civil war, or even worse, allow the sizable contingent of radical Islamists (and al Qaeda sympathizers) in the Pakistani army to seize control of the military—and Pakistan's nuclear arsenal.

Musharraf, a virtual dictator who seized power through a military coup, is not an ideal leader by American standards, but he's better than some of the alternatives (and worse than many others). A successful assassination could plunge Pakistan into a civil war, or even worse, allow the sizable contingent of radical Islamists (and al Qaeda sympathizers) in the Pakistani army to seize control of the military—and Pakistan's nuclear arsenal.