rotten > Library > Hoaxes > Temp Agencies

Temp Agencies

Brian

Lee's resumé showcases the mad skills of a motivated, dynamic,

detail-oriented I.T. professional with nearly half a decade of industry

experience under his belt. Brian

Lee's resumé showcases the mad skills of a motivated, dynamic,

detail-oriented I.T. professional with nearly half a decade of industry

experience under his belt.

Through no particular fault of his own, Brian's last job ended rather

unceremoniously

during a round of layoffs. At

age 28, he finds himself having been unemployed for close to five

years. Lately he's been checking out weekly job fairs at the local

community college, but so far the leads have been dismal. unceremoniously

during a round of layoffs. At

age 28, he finds himself having been unemployed for close to five

years. Lately he's been checking out weekly job fairs at the local

community college, but so far the leads have been dismal.

He's starting to suspect there's some kind of conspiracy

afoot, one meant to squish flat the essential bare necessities of

young people trying to make it in the world. Needless to say, he's

more than a whisper paranoid. "These days it seems like

even homeless people have better prospects than I do,"

Brian laments. "At least they've accepted their situation. I'm harboring

a lot of hope and blind faith that I'm gonna get

out of this situation, but the truth is I hate getting out of bed."

|

|

When

his savings account sagged just below twenty dollars, he grabbed a

handful of change and hopped on a bus to Placement Strategies, a temp-to-perm

employment agency square in the middle of downtown. When

his savings account sagged just below twenty dollars, he grabbed a

handful of change and hopped on a bus to Placement Strategies, a temp-to-perm

employment agency square in the middle of downtown.

He'd never been there before. The parking lot was filled with BMWs,

Jeep Cherokees, Mercedes convertibles and brand new

Explorers. He liked the abstract art hanging in the lobby.

Lush carpeting ran the length of looming mahogany hallways, offering

Brian immediate sanctuary and much-needed relief from his anxieties.

But after the receptionist greeted him with a half-hearted hello and

virtually no eye contact, everything fell apart. Nothing at Placement

Strategies was what Brian expected, and the whole "temp agency" experience left him with a

terrible taste in his mouth. |

| "I can do anything," Brian says. "I was jockeying for some kind

of systems administration position, but all they seemed to care about

was my typing speed. They treated me like a

retarded child. Like a data entry clerk."

|

Above: an ASIC designer places his fingers on the home keys. |

Placement Strategies set him up with an outdated version

of Microsoft Word, a pair of tubular headphones, and the audio

cassette of Tom Clancy's Air Force One, voiced by Wilford

Brimley.

The test was administered on an outdated PC with a dusty keyboard

yellowed with age. The software measuring his words

per minute didn't allow him to use the backspace key, so it looked

as though he was making dozens of mistakes. And then that was it.

The "introductory interview" was all over, and his resumé was

more or less politely dismissed. Brian grew incensed.

"I possibly raised my voice and

said some stuff," he remembers. "I specialize in server configuration.

Who the hell cares if I type thirty words a minute? I don't transcribe

fucking novels, I type filenames and cd

into dirs." |

|

| Junior Placement Strategist Dr. Edward Macavee [right]

was up front about Brian's test scores.

"His performance was disappointing to say the least.

We don't calculate how many words you can delete per minute.

Maybe when you're at home alone with the bong and your IRC friends,

missed keystrokes aren't a big deal. But a number of our clients

work on Wall Street, and typos there aren't gonna fly."

"When he finally left at three o'clock, Brian seemed bitter. He

insisted on taking the test again, suggesting I was somehow related

to Adolf Hitler. I gave him my speech about how

I'm sorry, how I don't make the rules... but I was shaking inside.

I was worried he'd come back with a rifle and take everyone out. He didn't seem like someone we'd feel comfortable

sending out into the world attached to our company's name and

reputation."

|

|

| Chad Willets was the receptionist that day. He's a thin,

sharply dressed 20 year old who speaks clearly and distinctly,

enunciating every syllable. He's outspoken, and not afraid to lay

it on the line. |

"Most candidates have a two-pronged strategy," he whispers. "Hoping

and moping. This isn't Jobs-R-Us, it's Placement Strategies. When

a mortgage company wants a data entry clerk, they want a chirpy, pleasant

blonde girl with a nice smile. Someone with an extensive

wardrobe of interesting clothes which aren't from Mervyns.

Someone who isn't jaded or sarcastic after five years of service in

the field. When a brokerage firm is hiring developers, again that's

code for send us a girl. That's all anyone

cares about anymore. Girls and blondes. These men in their offices

work hard. These are fucked-up times and

men need something to look at. Even women with smaller boobs

are securing rewarding careers." |

|

| Puzzle:

Which of the following four applicants is ineligible for hire? |

|

Chad's

supervisor, Barbara Flack [right], remembers Brian—but just barely.

Today she's peering through the rippled glass of her quiet office,

observing the latest crop of applicants. Chad's

supervisor, Barbara Flack [right], remembers Brian—but just barely.

Today she's peering through the rippled glass of her quiet office,

observing the latest crop of applicants.

They sit in straight-back Ikea chairs, clutching clipboards, filling

out preliminary paperwork with stubby golf pencils.

Some of them are bouncing their knees up and down. Others are staring

at the ground. Roberta's face is tightly pinched into a spazzed-out

Prozac smirk, like she wants a cigarette.

"More systems guys with scruffy beards," she

sighs. "I count one, two, three pot bellies. Each with a

T-shirt bearing the name of some ridiculous software product I've

never heard of." |

| She pauses. "Now one of them is talking to someone.

They're laughing about something. Christ, they're sitting there like

lumps waiting for something magical or positive to happen in their

lives. They've come here from twenty miles away on the bus or the

train just to get their heads chopped off in the big city." |

Formerly

with Oxford and Associates, Barbara has seen it all. Applicants who

don't do their laundry. Thirty-two year old men who arrive stoned

in the middle of the afternoon. She holds two different resumes up

to the fluorescent light, superimposing on one top of the other. Formerly

with Oxford and Associates, Barbara has seen it all. Applicants who

don't do their laundry. Thirty-two year old men who arrive stoned

in the middle of the afternoon. She holds two different resumes up

to the fluorescent light, superimposing on one top of the other.

"Interesting," Barbara muses. "These guys have identical work

histories, and each lists the other as a reference."

She hauls open a long metal filing cabinet packed with paper, and

struggles to stuff the incoming applications somewhere toward the

back.

"These dumbshits waltz in with forged documents containing phone numbers

of friends willing to pose as former employers. Like we've never seen

that before. Then they shuffle out disappointed, wondering why we

can't or won't place them." |

|   She

confides: "Systems administrators used to be mollycoddled with dainty

chocolate croissants piled high in every conference room. Same with

web designers, Java programmers or anyone claiming proficiency with

3D Studio Max. These days they're all just spoiled,

disposable human beings. They're a dime a dozen." She

confides: "Systems administrators used to be mollycoddled with dainty

chocolate croissants piled high in every conference room. Same with

web designers, Java programmers or anyone claiming proficiency with

3D Studio Max. These days they're all just spoiled,

disposable human beings. They're a dime a dozen."

Barbara is weary of the sarcastic remarks her

applicants mutter under their collective breaths. She's sad to report

that nobody wants them, not even at nine bucks an hour.

"I'd rather give my money to homeless people,"

she chuckles. Meanwhile, Brian Lee sits at the bus stop contemplating

his sorry situation. He faces a forty-five minute journey

back home, unless there's rush-hour traffic. It's the first of the

month, and his rent is due. He stares out the window, with nothing

further to say.

|

|

But thirteen stories above his head, in the same business

tower as Placement Strategies, entrepreneur Paul Humphries surveys

the city skyline with a pair of binoculars. He refers to himself

as a placement strategist of a different color, snorting at individuals like Brian, whom he labels a procrastinator.

"Guys like that love complicating their lives trying

to work for someone else. What if they stopped being pussies for

a split second and started taking a few real risks?

All you have to do is check your ego at the door, find something

simple which makes money, and the rest of your problems are solved.

Excuses are like elbows: everybody's got one or two and they're

all knob-shaped." |

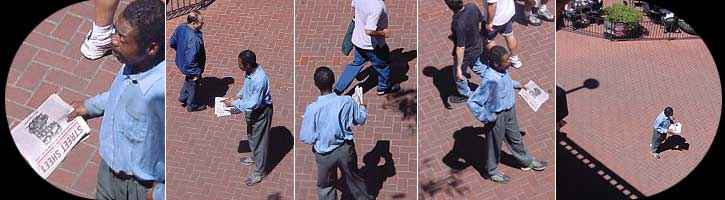

| He motions this reporter over to the window. "Look at that

guy down there selling Street Sheet. It's a generic homeless

rag, full of miserable poetry and anti-gentrification

whatnot. Even though he's wearing the regulation cornflower blue long-sleeved

collared shirt and charcoal Gap slacks, he won't sell a single copy.

I suspect he'll be out there all afternoon broiling under the sun.

But at least he's trying. At least he's got a product to push." |

|  "Yo

yo—who's up for the truth today? You sir?

Ma'am, can I interest you? Folks how's it going today?

Oh goddamnit." "Yo

yo—who's up for the truth today? You sir?

Ma'am, can I interest you? Folks how's it going today?

Oh goddamnit."

|

Paul's product is the Homeless Simulation Structure, something he came up

with six months ago after noticing something remarkably simple: homeless

people appear to do little more than just sit on the ground jingling a tin

cup, but still they manage to earn enough to stay alive week after

week. How is that even possible in a new millenium, where people need computer

skills to stay afloat? One common thread immediately ascertained is that

all these folks want help—and they're not afraid

to ask for it by name.

Paul

began studying homeless patterns the way an

oil painter might observe a landscape. "The most successful people

are those who are quiet, unobtrusive, almost completely out of sight.

If someone's all in your face, chasing you down the street, blubbering

away about how their car broke down or their wallet got stolen, your

brain clamps down and your purse strings draw shut. What a bunch of

horse shit. Get away from me. But if you're just

laying there sick-looking, totally harmless, the chances are much

greater you'll earn my respect." Paul

began studying homeless patterns the way an

oil painter might observe a landscape. "The most successful people

are those who are quiet, unobtrusive, almost completely out of sight.

If someone's all in your face, chasing you down the street, blubbering

away about how their car broke down or their wallet got stolen, your

brain clamps down and your purse strings draw shut. What a bunch of

horse shit. Get away from me. But if you're just

laying there sick-looking, totally harmless, the chances are much

greater you'll earn my respect."

Charitable contributions are predicated around the notion that

there really is a human being underneath every dirty

blanket, inside every cardboard box, or wedged way over yonder behind

that tumble-down shopping cart. The more Paul contemplated the different

lumps lounging around town, the more he wondered: what if they

didn't exist at all? What if that "homeless person"

camped outside McDonald's was really just a pair of plastic mannequin

legs partially hidden under a tarp? |

|

On a whim one morning, Paul assembled just such a prototype and

laid it forth facing a bustling street corner. To his astonishment,

it started making money within fifteen minutes.

Businessmen, mothers and grandmothers, even tourists stopped dead

in their tracks. Coins and dollars leapt from their pockets in earnest.

Not once did anyone stop to consider they were being

duped.

At the end of the day, Paul Humphries walked home with

ten dollars in change, a Chuck E. Cheese token, and a Burger King

coupon.

|

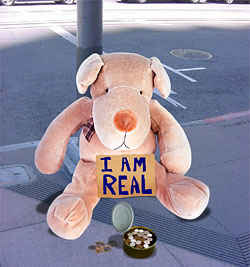

Early the next morning, filled with a newfound sense of

experimentation, Paul substituted an oversized stuffed animal in place

of the legs. This tactic generated some revenue, but not

as much as he would have liked.

Early the next morning, filled with a newfound sense of

experimentation, Paul substituted an oversized stuffed animal in place

of the legs. This tactic generated some revenue, but not

as much as he would have liked.

"Stick with a more realistic structure," he cautions. "The

floppy dog thing lasted exactly one afternoon and the results were

pretty much what you might expect. Nobody was particularly fooled

and the donations I accumulated weren't worth my getting out of bed."

He believes the all-important money cup will never be stolen,

as most everyone's unspoken assumption is that inside the structure

lives a desperate, possibly violent person who

sleeps with one eye open. Someone who's more or less hard to steal

from, someone who'd get very pissed off if anyone tried to dip into

his cash box. That message just isn't communicated with the presence

of cutesy artistic flair. |

Paul reminds us that no real crime beyond littering city

streets has taken place, and he insists that all his structures

have been assembled from household materials. Just roll a pair of tube socks

down the fat ends of a couple baseball bats, and attach flip-flop sandals

or worn-out tennis shoes. Leave them sticking out a few inches from underneath

a tarp to flesh out the illusion of a human being. Who

stares at a homeless guy's legs for more than a couple of seconds?

Believe it or not, it was that initial Chuck E. Cheese token

which inspired Paul to move forward with his next endeavor: animatronic

homeless people capable of delivering prerecorded pleas for cash,

voiced by Wilford Brimley.

Believe it or not, it was that initial Chuck E. Cheese token

which inspired Paul to move forward with his next endeavor: animatronic

homeless people capable of delivering prerecorded pleas for cash,

voiced by Wilford Brimley.

Pictured [right] is the skeletal prototype of "Clyde," in

one of his earliest incarnations. Clyde was beta-tested in Chicago

and New York, where he sat in one place for eight hours. At the end

of his shift, he'd earned sixty dollars! |

#

HSS randomly rotating phrases

# broadcast when triggered by

# motion sensor (rev 3.4.3)

%ClydeStrings =

(

"p0" => "Can I have some change?",

"p1" => "Can I have some change?",

"p2" => "Can I have some change?",

"p3" => "Can I have some change?",

"p4" => "Can I have some change?",

"p5" => "Can I have some change?",

"p6" => "Can I have some change?",

"p7" => "Can I have some change?",

"p8" => "Can I have some change?",

"p9" => "Can I have some change?"

); |

|

But Paul's business really blossomed

after striking a quiet deal with the Real Doll Corporation, a company

known for life-size silicon-based

sex partner substitutes. His structures since then have grown so elaborate, so detailed

and realistic you'd swear he's commissioned a battery of Disney's

Imagineers.

"I enjoyed Spielberg's A.I. and I love the Jamboree

Bears," he says. "Certainly each has its own

novelty, but neither is designed to put food on my table. They're

examples of what I call technology going to waste."

Like any cinematic special effect worth its salt,

subtlety is the goal. The latex surrounding each human figure is

cured in the sun to provide a weather-beaten appearance. Costumes

courtesy of the Salvation Army. |

| He gestures toward "Stephen,"

a mopey, silicon-filled human form complete with scraggly blonde horsehair

and thrift store clothes. A small motor allows him to wobble slowly

back and forth, rotating a cardboard sign along the pivotal axis of

his left wrist. Total cost: $8000.00. |

|

|

"You just don't want people to know one way or another what's going on,"

Paul whispers. "Maybe Stephen's a teenage runaway down on his luck, maybe

he's an animatronic robot I licensed from Chuck E. Cheese. People feel a

little empathy and they chip in. That's the name of the game. He's practically

my son. And wouldn't you know it, he's got a great job and he supports his

family. Stephen cleans up big time."

Granted,

a handful of dollars here and there may not seem like much for all the

trouble Paul's gone through. But in six short months, he's installed fifteen

hundred fake homeless people in major cities across the United States. Granted,

a handful of dollars here and there may not seem like much for all the

trouble Paul's gone through. But in six short months, he's installed fifteen

hundred fake homeless people in major cities across the United States.

The daily net of Paul's invisible army averages close to $100,000.

What it loses on weekends it more than makes up for during Thanksgiving

and Christmas. Homeless Simulation Structures earn Paul well over three

and a half million dollars a year, and every last coin is tax free.

"This October I'm buying my second house," he beams with pride. "Near

the beach. No homeless types whatsoever. No one bugging me for stuff.

I've already hired a few of my girlfriends to go running around collecting

cash from all the cups, and things are going just great. I could never

go back to a goddamn cubicle. Not in a million years. I'm more than happy

squeaking by on my hourly wage. I've got a life to live, and I'll bet

you do too."

|

Pornopolis |

Rotten |

Faces of Death |

Famous Nudes

|