|

Siamese Twins A lot of people hate the term "Siamese Twins", just like they hate terms like "Welsh on a bet" or "Indian Giver".

A lot of people hate the term "Siamese Twins", just like they hate terms like "Welsh on a bet" or "Indian Giver". The alternative phrase, "Conjoined Twins" is pretty tame and has become the politically correct way to refer to this strange biological phenomenon.

Siamese twins can't be "conjoined" because they were never separated in the first place, which leaves us in a semantic quandary that can only be resolved by a swift and totally arbitrary ruling. Like it or not, you're stuck with "Siamese twins" until somebody thinks of something better... or at least until the end of this article. Siamese twins are formed when identical twinning goes awry. The cause of the syndrome is unknown, but it's suspected to be caused by environmental factors. (A high incidence of Siamese twinning was reported in areas of Vietnam exposed to Agent Orange, for instance.) Identical twins are formed when a single embryo unexpectedly divides into two embryos which bear identical DNA. Siamese twins result when an embryo starts to divide, but fails to complete the process.

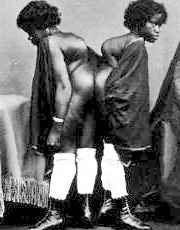

Depending on how much of the twin(s) is (are) shared, the phenomenon raises some headache-inducing questions about just what makes an individual person individual. For instance, are you two people if you have two heads? What if you share a heart? A spinal cord? What if you're just joined at the buttocks (one of the more common and viable forms of Siamese twinning)? Where does one twin end and the other begin? It's impossible to construct a one-size-fits-all answer to this conundrum, because the possible configurations are virtually unlimited.

Types of Not-Really-Conjoined TwinsThere are several major types of Siamese twins, each one stranger than the last—assuming you arrange them in increasing order of strangeness. Which is what we have, in fact, done.

The primary types listed above cover the vast majority of Siamese twins, but there are even more exotic possibilities, most of which are extraordinarily rare and even more mind-bending. These include:

Famous Not-Really-Conjoined TwinsAlthough there are scattered historical hints, there are few definitive records of Siamese twins until the second millennium, and most of those are even more recent. The vast majority of Siamese twins are stillborn even today, and that mortality rate was much higher before the dawn of modern medicine.

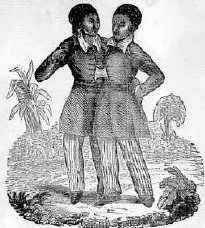

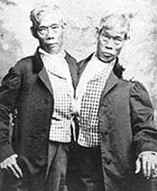

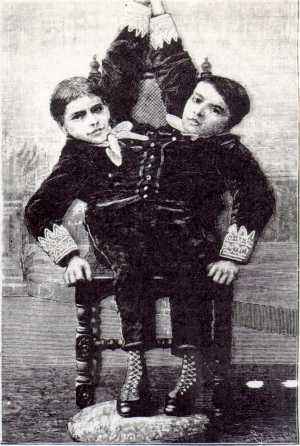

Toward the beginning of the Middle Ages, occasional reports of Siamese twins began to surface (although no one called them that). The Biddenden Maids were a celebrated pair of British women around 1100 who were supposedly joined at both the hips and the shoulders (medically unlikely). Other reports were less whimsical, including a few stories about disastrous and lethal attempts at separation. The first successful separation was reported in 1689, but even then, the many kinds of Siamese twins (still not called that) made such operations extraordinarily rare. The 19th century saw the birth of the most famous Siamese twins in history, Chang and Eng Bunker, who can be legitimately called Siamese twins, primarily because they were Siamese.

In retrospect, Chang and Eng were excellent medical candidates for separation, but risks were judged to be too great during their lifetimes. The two stayed together and eventually earned their own money performing as a freak-show and "scientific display" known as the Siamese Twins. As survival rates and mass communication techniques improved, the number of documented Siamese twins grew dramatically over the next 200 years. Many Siamese twins (like the Tocci Brothers of Italy) became celebrities in their own right. Others managed to carve out reasonably normal lives for themselves, including marriage (often to non-connected siblings) and children. After retiring from the circus, Chang and Eng lived into their 60s and fathered more than 20 children between them.

Separation Anxiety Although the first successful separation was reported in the 17th century, the definition of "successful" is pretty dicey. The earliest separations were performed when one of the twins was gravely ill or had already died, in an effort to save the other.

Although the first successful separation was reported in the 17th century, the definition of "successful" is pretty dicey. The earliest separations were performed when one of the twins was gravely ill or had already died, in an effort to save the other. Because the surgery was most often performed on older Siamese twins, the physical and psychological shock of separation was usually too much to bear, especially when one of the twins died. The surviving twin would linger for weeks or even months—but rarely years.

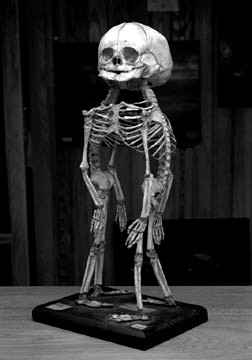

The earlier the surgery is performed, the better the chance that the separated twins can have something resembling a normal life. Today, doctors are able to tackle even the more difficult forms of Siamese twinning, such as craniopagus twins attached at the head, with a reasonable chance of success.

The many possible configurations of Siamese twins make it impossible to craft a single answer to the question: "Should they be separated?" Some twins, like Chang and Eng, have very little actual overlap in their bodies. For all intents and purposes, they were two different people and it would be an easy call—both medically and ethically—to separate them if they were born today. Similarly, no one gets worked into a lather if excess body parts are trimmed from a Siamese twin with a single brain. Of course, it's the other cases that you hear about. As separation techniques have improved, the parents of some Siamese twins have been forced into a literally Solomonic dilemma: do you kill one twin so that the other can live?

The case of Gracie and Rosie Attard, born in 2000 in Britain, was exemplary of the problem. Gracie and Rosie were joined along the chest and abdomen, but only had one heart between them. Gracie had a normally functioning brain, while Rosie had an underdeveloped brain. Because of the way their connection was configured, doctors determined that both would die if they were not separated. The Attard case prompted an especially huge brouhaha, because the parents (who were Roman Catholics) believed killing the underdeveloped twin was murder and refused to allow separation. The issue got even stickier when a British court overruled their wishes and ordered doctors to separate the twins (an issue aggravated even more deeply by the fact the Attards were not British citizens). Another stir erupted in 2003, when an adult Siamese twin pairing sought separation of their own accord. Laleh and Ladan Bijani were joined at the head. They had spent their 29 years of life dreaming of the day when they would be separated from each other. Unfortunately, both of them died during the 50-hour operation.

Some members of the pro-life lobby have also strenuously objected to any procedure which risks the lives of either twin, no matter how incomplete that twin might be. The most recent example was Manar Maged, an Egyptian girl who was born with an extra head, which prompted howls of outrage from bloggers and holy rollers who swore that if the head could smile—which it could—it must be considered a fully participating human being. The second head was removed in 2005 and Maged is reportedly recovering well. Obviously, it's an extremist view to insist that any given mass of flesh automatically qualifies as a human life, but the issue does raise reasonable questions about what exactly is normal and human, and what isn't. In 2000, Lori Schappel, one half of an adult "conjoined" pair, told the BBC: "We never wanted to be separated, we never do want to be separated and our families never ever wanted us separated because we fully believe that God made us this way and He had a purpose for us and you do not ruin what God has made."

Speculation on this point has led to lectures and books with titles such as "Conjoined Twins and the Future of Normal" and the growth of advocacy groups which urge society to embrace Siamese twins as part of an expanded definition of "normal" which can include hermaphrodites and other unusual birth configurations such as dwarfism and gigantism. Of course, you run into the same problem with "normal" here that you encounter with "conjoined." Normal means "the usual or expected state, form, amount, or degree." Conjoined twins are neither conjoined nor normal, but how about this? They're "OK"—which means "agreeable; acceptable." Life-threatening conditions aside, you'd have to be a cold-hearted bastard to tell perfectly functional human beings that he, she, they or it are not acceptable on prima facie grounds. I'm OK, you're OK, midgets are OK, giants are OK, elephant men are OK, hermaphrodites are OK, Siamese twins are OK. "And I think to myself, what a wonderful world..."

|

Unfortunately, the term is completely inaccurate, since "conjoined" means "to join or become joined together, or to unite," which is exactly the opposite of what happens in these cases.

Unfortunately, the term is completely inaccurate, since "conjoined" means "to join or become joined together, or to unite," which is exactly the opposite of what happens in these cases.

The result is not quite two children. Wherever the embryo stopped dividing, the twins that would have been melt back into a single entity. Siamese twins occur in one of every 200,000 live births, which works out to between one and two births per day worldwide (although many of these do not survive long).

The result is not quite two children. Wherever the embryo stopped dividing, the twins that would have been melt back into a single entity. Siamese twins occur in one of every 200,000 live births, which works out to between one and two births per day worldwide (although many of these do not survive long). Siamese twins who survived childbirth also had (and continue to have) a much lower life expectancy than other children. Many ancient socieities—including Greece, Egypt and Rome—routinely practiced infanticide and euthanasia on children born with birth defects.

Siamese twins who survived childbirth also had (and continue to have) a much lower life expectancy than other children. Many ancient socieities—including Greece, Egypt and Rome—routinely practiced infanticide and euthanasia on children born with birth defects.  Chang and Eng were connected by a short length of skin on their chests. They were born in what was then Siam in 1811 and sold to the circus by their mother when they were teenagers.

Chang and Eng were connected by a short length of skin on their chests. They were born in what was then Siam in 1811 and sold to the circus by their mother when they were teenagers. Medical advances since the 1960s have dramatically improved separation success rates. One reason for this improvement is that doctors have begun operating early, before babies become fully developed and before the brain starts to lock in neural pathways based on the connnected state.

Medical advances since the 1960s have dramatically improved separation success rates. One reason for this improvement is that doctors have begun operating early, before babies become fully developed and before the brain starts to lock in neural pathways based on the connnected state.  But there are still problematic cases, in which the shared properties of twins prompt deep and difficult moral questions and provoke great outbursts of semi-hysterical handwringing by large groups of people who have no relevant life experience on which to base their opinions.

But there are still problematic cases, in which the shared properties of twins prompt deep and difficult moral questions and provoke great outbursts of semi-hysterical handwringing by large groups of people who have no relevant life experience on which to base their opinions.  Usually, the only time this option is considered is when both twins will die without separation: When two children with two fully functioning brains share a single heart, obviously only one can survive the separation.

Usually, the only time this option is considered is when both twins will die without separation: When two children with two fully functioning brains share a single heart, obviously only one can survive the separation.  Sticky situations like these have inspired long and mostly tiresome debates about the ethics of separating Siamese twins at all, with some doctors going so far as to argue that separating the "conjoined" is mutilating one (or two) of God's creatures, at least in cases where the Siamese twins are capable of surviving joined.

Sticky situations like these have inspired long and mostly tiresome debates about the ethics of separating Siamese twins at all, with some doctors going so far as to argue that separating the "conjoined" is mutilating one (or two) of God's creatures, at least in cases where the Siamese twins are capable of surviving joined.  Whether or not you want to bring God into it, the question of what's right and proper looms large over any discussion of medical treatment for Siamese twins.

Whether or not you want to bring God into it, the question of what's right and proper looms large over any discussion of medical treatment for Siamese twins.