|

Firewalking There's a certain mystical cachet to walking across hot coals or burning embers, but the actual process is no more spiritual than healing a bacterial infection with penicillin.

There's a certain mystical cachet to walking across hot coals or burning embers, but the actual process is no more spiritual than healing a bacterial infection with penicillin. From early Christian sects to Buddhism, from Hinduism to animistic aboriginal religions]], holy men and women of every philosophical bent have exploited the extraordinary theatrical spectacle of fire-walking. The basic idea goes like this: You set a big bonfire over about eight to 12 feet, and when the fire has burned down to smoldering coals, you walk across the coals. If you're doing it right, you emerge on the other side unscathed. Virtually every religion has dabbled in firewalking at one point or another, some more deeply than others. The geographic dispersion of firewalking suggests it must have been one of humanity's earliest rituals. The tradition is most visible in India, Africa and North America, but it can be found in China, Japan, Europe, Australia, South America and beyond. While most prominent in shamanic religions, firewalking has been used to prove a point about faith in Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, Judaism and Sufi Islam. Even Christianity has a history with the practice—Saint Peter Igneus was celebrated for performing a relatively mundane act of firewalking. Despite these widely diverse religious schemes, the firewalking ritual is pretty consistent from one culture to the next. It's most commonly used for one or more of the following purposes:

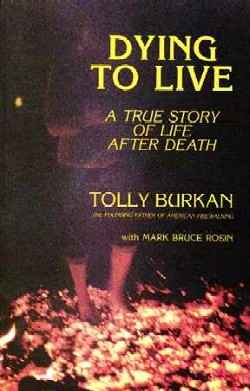

The trick is to keep a brisk, even pace. Hot coals are not good conductors of heat, and the soles of your feet have relatively thick skin. If you keep an even pace, you'll probably be all right. That doesn't mean this is a risk-free venture. If you walk too slow, the heat will penetrate and you'll get burned. If you panic and start running, the impact of your feet hitting the coals will allow the heat to penetrate and you'll get burned. Whatever you do, don't stop walking. There are other potential complications as well. For instance, a coal can crumble under your foot and stick to your skin. Your pants or skirt can catch fire. And, of course, if you trip and fall, your faith will probably not protect you from hideous and disfiguring injuries. For all these reasons, in addition to basic common sense, it's probably best not to undertake a firewalk without professional training. Luckily, you don't have to live among aboriginal shamans to learn the technique. Western civilization rediscovered firewalking during the late 1970s. There are plenty of people who are eager to take credit for this development. The most vocal self-promoter in this respect is Tolly Burkan, a New Age self-empowerment guru who has proclaimed himself "the founding father of firewalking" and openly sneers at everyone else who teaches firewalking, even those who learned it from him.

As you can infer from the above, firewalking won't solve all of your lingering personality issues. But it's not an experience lightly dismissed either. The reason firewalking is so effective in religious ritual—or, more recently, as sideshow entertainment or corporate leadership training—has to do with a deeply ingrained fear of fire common to virtually all of the Earth's creatures. Taming fire is arguably humankind's greatest accomplishment. Certainly, it represents a triumph of intellect and spirit over the deeply ingrained animal instinct to fear flames. Like smoking, firewalking is a celebration of man's mastery of fire. Even the skeptics admit that the emotional impact of firewalking is overwhelming. The adrenaline rush of a firewalk can be very empowering and transformative, and the entire process represents a reasonably healthy confrontation with fear—like skydiving or eating blowfish.

Firewalking can also be fairly effective in its role as judge, jury and executioner. The phrase "trial by fire" derives from the practice of making an accused person firewalk in order to prove their innocence or guilt. The theory here is that the innocent will pass through the fire unharmed, while the guilty will be burned. In cultures where firewalking hasn't been demystified by science-minded killjoys, there's a reasonable chance this approach would play to the cultural expectations of the walker, causing guilty parties to panic, step wrongly and suffer the consequences. Granted, this form of criminal justice isn't infallible, but then what system is?

Imperviousness to FireThe concept of "trial by fire" isn't strictly limited to firewalking however. Firewalking isn't the same as imperviousness to fire or heat.The Inquisition employed several "trial by fire" techniques to identify heretics or witches. Considerably less forgiving than firewalking, these methods included searing suspected witches with hot irons or burning them at the stake. Virtually no one passed these examinations.

There are other scattered reports of immunity to fire as a miraculous event in various religious contexts, such as in Voudoun, where individuals who have been possessed by the gods become temporarily invulnerable. There are numerous anecdotal reports of voodoo ritual participants displaying imperviousness to fire. While impressive, these accounts are not especially verifiable. Even in anecdotal reports, immunity to fire usually comes off as a dangerously unreliable phenomenon. On the one hand, you have the Old Testament story in which God rescues Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego from the fire simply to make a point about idol worship. On the other hand, you have 19-year-old Joan of Arc, whom God callously abandons to an excruciating death at the stake, only to preserve her heart and "entrails" from the flames. As moral victories go, this seems pretty feeble. The historical record strongly suggests you stand a better chance of surviving an inferno armed with a chemical fire extinguisher than with a rosary. "He" might move in mysterious ways, but chemistry is reassuringly predictable.

|

That said, there is nothing particularly miraculous about walking on hot coals. Though there are scattered examples of cultures which treat the feet with oils or drugs, it's possible to walk on hot coals without the benefit of either.

That said, there is nothing particularly miraculous about walking on hot coals. Though there are scattered examples of cultures which treat the feet with oils or drugs, it's possible to walk on hot coals without the benefit of either.

"Tolly literally created a new paradigm, and later instructors merely had to follow in his footsteps," his Web site proclaims, notwithstanding thousands of years of history and his ex-wife's claim that they were both taught the technique by literally following in someone else's footsteps.

"Tolly literally created a new paradigm, and later instructors merely had to follow in his footsteps," his Web site proclaims, notwithstanding thousands of years of history and his ex-wife's claim that they were both taught the technique by literally following in someone else's footsteps.  Such intense experiences can be channeled to produce specific mental or spiritual results, especially if the walker is conditioned in advance to associate the process with any given religious context or other expectations, which is why firewalking is so effective as an initiation ritual.

Such intense experiences can be channeled to produce specific mental or spiritual results, especially if the walker is conditioned in advance to associate the process with any given religious context or other expectations, which is why firewalking is so effective as an initiation ritual. According to folklore, salamanders are impervious to flames, and they were sometimes used to create

According to folklore, salamanders are impervious to flames, and they were sometimes used to create