|

The Historical Construction of The Biblealterations within the old testament Because the Old Testament books of the Bible are essentially translations of the Hebrew Bible (or Tanach), the story of the Bible's construction and frequent reconstruction begins with that of the first 5 books of the Hebrew Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Also known as the Torah or the Pentateuch, these early books are fabled to have been written by Moses. According to legend, the first four were given by God himself in dictation, while the fifth was wholly authored by Moses.

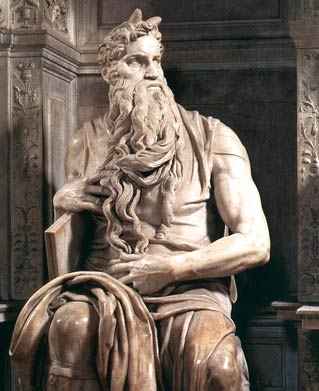

Because the Old Testament books of the Bible are essentially translations of the Hebrew Bible (or Tanach), the story of the Bible's construction and frequent reconstruction begins with that of the first 5 books of the Hebrew Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Also known as the Torah or the Pentateuch, these early books are fabled to have been written by Moses. According to legend, the first four were given by God himself in dictation, while the fifth was wholly authored by Moses.

Rabbinical scholars, studying the Jewish Torah and other texts point out that there is no actual written evidence for this folkloric belief, noting that only four passages are actually credited to Moses by scripture. Christian scholars reached this same conclusion in the 18th century, after extensive textual analysis revealed that while Moses may have contributed to early drafts of the Torah, he certainly could not have written the whole thing himself. To begin with, the final book of the Torah ends with an account of Moses' own death and burial, and is written in the third person. Clearly, this portion at least was added by someone else. As scholars continued their close textual examination, they discovered significant variations of style, language, and ideology throughout the 5 books. The degree and quality of the variations indicated that various authors, living at distinctly different time periods, had composed different portions of the Torah.

The evidence thus far suggests that the Torah was the collective work of four or five authors and that in all probability it was edited and altered by yet more individuals over the course of time. It is useful to note here that religious scholars place the time of Moses at 3300 to 3450 years before the present. Perhaps, as some conservative religious scholars assert, all this editing and redacting was divinely guided. Perhaps the entire three and a half thousand year process of editing, deleting, and revising was done wholly according to some divine will, and human bias and ambition never entered into it (although this implies that earlier drafts of the Bible were wrong, so how do we know if anyone's gotten it right yet?). And perhaps no part of the text was ever lost due to accident or decay prior to being edited into the final form of the Torah. Ultimately, we can only wonder. No records survive to tell us what really happened. We know that changes occurred, but no one leaves a memo revealing why. However, if we were to infer from modern experience, such as the changes and revisions that affect state laws and the U.S. Constitution (cf. Sodomy and the Supreme Court), or even from historical changes made to Christian scriptures for political reasons, then we would tend to conclude that in ancient times, as in more recent centuries, spiritual doctrines were frequently altered or even suppressed to suit the political needs and personal beliefs of those in power. Meanwhile, we certainly do know that the Tanach/Hebrew Bible continued to undergo additions and revisions over time. Additional books (Prophets, Writings) were added, with changes or redactions made here and there to the wording of these texts, possibly to bring scripture into alignment with the moral and political climate of the day.

But simply copying and distributing more volumes would not be enough. Hebrew was fast becoming the dead language of scholars. The majority of Jews now spoke a dialect of Greek. Greek was also the written language of commerce, personal correspondence, and other mudane tasks. Thus if more Jews were to have access to scripture—whether through reading it or through having it read to them—the Tanach would have to be translated into Greek. The resultant translation was called the Septuagint, a name which refers to the seventy scholars who, according to legend, were locked in different rooms and all eventually emerged with the same translation. (Historians claim the Septuagint was more likely the product of a series of translations over time.)

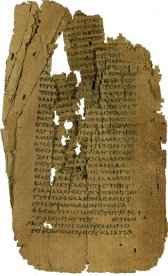

First, prior to the 6th century A.D., the written Tanach consisted primarily of consonants. To be able to actually translate the written text into understandable and meaningful words, one would have to receive special instruction by a teacher or rabbi. Knowledge of this correct interpretation or reading was passed down orally from teachers to students over the generations. Second, as if to further confuse matters, words were written without spaces in between. Thus knowledge of where one word ended and another began was, as with vowel sounds, dependent on the oral tradition. The significance of these practices is that they opened the door to error and gross mistranslation. This would prove to be a serious problem in the Christian era, as those who had never received such training attempted to decipher the meaning of Hebrew language texts. However, since the discovery of "Old Testament" texts among the so-called Dead Sea Scrolls of Qumran, historians now know that dissent and discrepancies had been creeping into interpretation/transliteration of the scriptures for centuries. Simply put, transcribing the words without vowels or word breaks allowed different people to read different meanings into the text.

|

Some variations might be explained by the fact that the Torah once existed in many different versions and editions. These were then copied and recopied over the centuries, until they were gathered up by Jewish scribes and cobbled into a single, reasonably consistent text. However, Bible/Torah scholars maintain that this fact, on its own, does not sufficiently explain the anomalies, unless of course what had existed prior to this process was not the Torah as such (i.e. not just different versions of the Torah), but an assortment of other religious texts, edited together to form a single narrative. The resulant work, repackaged as the Torah, was then passed along to later generations and mythologized as having always been a single narrative, told by one single man—Moses. This mythology (that the Bible was created as a whole, direct from the mouth of God) would later be inherited by Christians, who would use this mythology to justify the torture and execution of anyone who dared question it's contents or construction, an approach epitomized by the

Some variations might be explained by the fact that the Torah once existed in many different versions and editions. These were then copied and recopied over the centuries, until they were gathered up by Jewish scribes and cobbled into a single, reasonably consistent text. However, Bible/Torah scholars maintain that this fact, on its own, does not sufficiently explain the anomalies, unless of course what had existed prior to this process was not the Torah as such (i.e. not just different versions of the Torah), but an assortment of other religious texts, edited together to form a single narrative. The resulant work, repackaged as the Torah, was then passed along to later generations and mythologized as having always been a single narrative, told by one single man—Moses. This mythology (that the Bible was created as a whole, direct from the mouth of God) would later be inherited by Christians, who would use this mythology to justify the torture and execution of anyone who dared question it's contents or construction, an approach epitomized by the  Eventually, between 300 and 100 BC, under the Roman Empire and Roman Law, Jewish cultural and national identity was crumbling. If the Jews were to continue as a people, and if they were to keep the covenants made with God through Abraham and Moses despite being scattered and increasingly influenced by gentiles, they would need ready access to the scriptures.

Eventually, between 300 and 100 BC, under the Roman Empire and Roman Law, Jewish cultural and national identity was crumbling. If the Jews were to continue as a people, and if they were to keep the covenants made with God through Abraham and Moses despite being scattered and increasingly influenced by gentiles, they would need ready access to the scriptures.

The translation of the scriptures into Greek proved to be an important turning point in the development of the Christian Bible, as we shall

The translation of the scriptures into Greek proved to be an important turning point in the development of the Christian Bible, as we shall