|

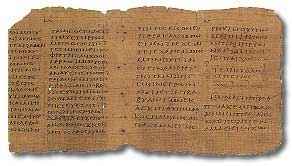

The Co-opting of the Tanach Translating the Tanach, or Hebrew Bible, into Greek (300-100 B.C.) was to have consequences the Jews had never foreseen. As the teachings of Jesus Christ grew in popularity, his following expanded among the gentiles, most of whom spoke Greek, not Hebrew. The Septuagint, the Greek language version of the Tanach/Hebrew Bible, allowed these Greek speaking Christians access to the scriptures so often referenced by Jesus and the Apostles. No doubt they hoped to gain some greater insight into Jesus' mysterious parables through reading Jewish scripture. In addition, within the Septuagint, the Christians found references and prophecies which seemed to validate their belief that Jesus was the Messiah, the blessed savior long foretold by the prophets of Judaism.

Translating the Tanach, or Hebrew Bible, into Greek (300-100 B.C.) was to have consequences the Jews had never foreseen. As the teachings of Jesus Christ grew in popularity, his following expanded among the gentiles, most of whom spoke Greek, not Hebrew. The Septuagint, the Greek language version of the Tanach/Hebrew Bible, allowed these Greek speaking Christians access to the scriptures so often referenced by Jesus and the Apostles. No doubt they hoped to gain some greater insight into Jesus' mysterious parables through reading Jewish scripture. In addition, within the Septuagint, the Christians found references and prophecies which seemed to validate their belief that Jesus was the Messiah, the blessed savior long foretold by the prophets of Judaism.

Understandably, most Jews did not appreciate having their holy book co-opted by an upstart religious cult—especially one that had clearly misunderstood the mission of their (long awaited, and still awaited) Messiah. Worse yet, having propped up their own leader as a false Messiah, these Christians were now spreading his fame, and his heretical teachings, far and wide to all who would listen. As far as mainstream Judaism was concerned, not only was Jesus not the Messiah, he wasn't even a real prophet. In fact, there had been no new prophets in roughly the 500 years since the closing or canonization of the Prophets portion of the Tanach. To amend this concept and acknowledge Jesus as a true prophet was absurd. His apparent teachings threatened the very foundations of Jewish society: the Law of Moses and the power and leadership of the priests. Meanwhile, Christians were mixing the Torah and other scriptures of the Tanach (i.e. the Jewish scriptures) with texts generated by their own cult - and presenting both as co-equal scripture. What's more, the rituals of the Early Christian Church were direcly borrowed from rituals performed in the Jewish synagogue, further blurring distinctions. Finally, the Christians were an evangelical cult, actively seeking and recruiting new members—Jew and gentile alike. Increasingly, Jewish leaders felt the need to draw a sharp distinction between "true" scripture and the various other writings in circulation. It would not do for Jews, especially those living in far flung posts of the Roman Empire, to become confused about their own religious heritage and doctrine. Such confusion could take them down the same misguided path trod by Christians - a path which included, among other things, abandoning kosher food rules and all observance of sacrificial duties, as well as the rite of male circumcision. Such a mode of living might be fine for gentiles, but Jews were the "chosen people", meaning they were required by God to uphold the agreements of their covenant with him, negotiated through Abraham and Moses, which required the very customs and observances that Christians were ignoring. Moreover, it might be said that the common thread (and threat) that ran throughout Jewish scripture was the idea that God abandons his chosen people when they forget to honor that covenant. Without God's support, they would repeatedly found themselves helpless before their enemies—a point which was surely on their minds after Rome destroyed the Second Temple in 70 A.D.

The texts excluded by these criteria, which had been present in the Septuagint, included Baruch, Judith, Sirach, Tobit, Wisdom, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and parts of Daniel and Esther. The Council also excluded a number of other books that once were in circulation as part of the Writings portion of the Tanach, though it is not clear whether any of these were ever truly deemed scripture. Part of the reasoning behind the "written in Hebrew" requirement was surely the exclusion of Christian influenced works, as almost all of these were written in Greek. But a larger purpose must have been to preserve Jewish culture from annihilation through assimilation. If the Jews could not maintain their national identity as a political entity (that having been already crushed by Rome), then they would need to preserve a cultural identity or risk disappearing as a people. Ultimately, this goal was achieved through maintaining their own separate language, as well as other distinctive practices which set them apart no matter where they emigrated. The irony here is that the Greek language Septuagint, which had originally come into being in order to preserve Jewish culture, was now being abandoned hundred of years later for the same purpose—to preserve Jewish culture.

For example, according to Christian mythology, Jesus had been the product of a virgin birth. The prediction that the savior would be of virgin birth could only be found in the Septuagint: "'Look, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall name him Emmanuel' which means, 'God is with us.'"Interestingly, while Greek translators interpreted the word almah as "virgin" in this passage, it actually means "the young woman". The word which meant "a virgin", was actually besulah. Oddly, elsewhere in the Septuagint, translation is in more in accord with this usage. Not surprisingly, Christian theologians who have acknowledged the error have attributed it to divine action, that is, to God paving the way for correct understanding of Jesus' role. Jews do not share this interpretation. Ultimately Christianity would retain the Septuagint, paired with assorted New Testament texts, for many centuries to come, although it would modify it drastically by translating it a second time—this time into Latin. The later revisions of this Latin translation would come to be known as the Catholic Bible.

But of course, long before any of these developments came to pass, the Christian faith would continue to fall ever more heavily under the influence of the Roman Catholic Church, a body which would profoundly change the nature and purpose of Christian worship, the politics of Western Civilization, and the usage and content of the Bible.

|

In response to this disturbing development, Jewish religious leaders convened the Council of Jamnia in 92 A.D., determined to separate true scripture from wannabe texts and outright heresy, Christian or otherwise. According to the Council, for a text to be retained as official scripture, it must:

In response to this disturbing development, Jewish religious leaders convened the Council of Jamnia in 92 A.D., determined to separate true scripture from wannabe texts and outright heresy, Christian or otherwise. According to the Council, for a text to be retained as official scripture, it must:

Meanwhile, Christians had no problem with using the Septuagint. In fact, its usage was vital to the spread of their religion, as it would be nearly 500 years before the Hebrew language texts of the Tanach/Hebrew Bible became accessible as a stand-alone text—that is, without requiring oral instruction by a Rabbi. Rabbinical instruction was generally not available nor desirable to gentile Christian converts, but the Septuagint was already available, not to mention highly accessible, being written in a language they already knew, Greek. Christians also found the Septuagint version to be in greater accord with their own doctrines: specifically, only the Septuagint contained references and turns of phrase that supported their own claim that Jesus was the Messiah.

Meanwhile, Christians had no problem with using the Septuagint. In fact, its usage was vital to the spread of their religion, as it would be nearly 500 years before the Hebrew language texts of the Tanach/Hebrew Bible became accessible as a stand-alone text—that is, without requiring oral instruction by a Rabbi. Rabbinical instruction was generally not available nor desirable to gentile Christian converts, but the Septuagint was already available, not to mention highly accessible, being written in a language they already knew, Greek. Christians also found the Septuagint version to be in greater accord with their own doctrines: specifically, only the Septuagint contained references and turns of phrase that supported their own claim that Jesus was the Messiah.

1,000 years later, the Septuagint would become even more identified with the newly emergent Orthodox Christian Church. Shaking off the Roman Catholic Church's demand of total subservience and obedience, the Greek speaking Orthodox Church established itself as a thoroughly independent entity. Naturally, to avoid the taint of heresy, the Orthodox Church portrayed itself as remaining true to the original Christian Church while the Catholic Church broke away in a strange and offensive new direction. This schism between Rome and Constantinople (formerly heads of the Western and Eastern branches of the Church) would serve as a model for later schisms in the faith, 1500 years after the birth of Christ.

1,000 years later, the Septuagint would become even more identified with the newly emergent Orthodox Christian Church. Shaking off the Roman Catholic Church's demand of total subservience and obedience, the Greek speaking Orthodox Church established itself as a thoroughly independent entity. Naturally, to avoid the taint of heresy, the Orthodox Church portrayed itself as remaining true to the original Christian Church while the Catholic Church broke away in a strange and offensive new direction. This schism between Rome and Constantinople (formerly heads of the Western and Eastern branches of the Church) would serve as a model for later schisms in the faith, 1500 years after the birth of Christ.