|

National Security Letter The list of "compromises" between liberty and security in the post-September 11 era gets longer every day, but the worst part is that some of those "compromises" make it illegal for anyone to figure out just how many "compromises" have been added to the tote board.

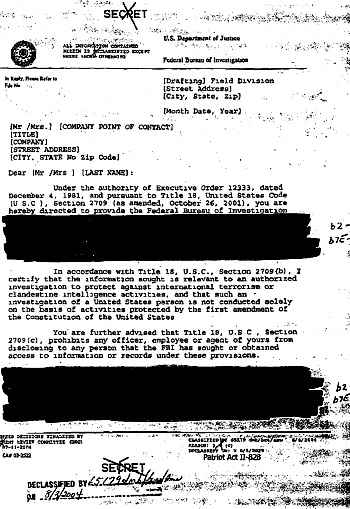

The list of "compromises" between liberty and security in the post-September 11 era gets longer every day, but the worst part is that some of those "compromises" make it illegal for anyone to figure out just how many "compromises" have been added to the tote board. Consider the brave new tool known as the National Security Letter, one of the PATRIOT Act's many Easter Eggs, provided for in Section 215 of the 131-page homeland manifesto. National Security Letters are nothing less than warrantless searches—so secretive that to disclose the very request is itself a prosecutable violation of national security. NSLs are issued by FBI agents, without so much as a nod to the courts. They are directed to businesses, usually demanding they cough up information on their customers. The companies must comply and cannot even disclose the fact that a request was received. And if you're thinking this tool is being judiciously and selectively used to protect the United States against terrorists, think again. More than 30,000 NSLs are issued every year, according to the Washington Post. And that's just an estimate from anonymous sources. The actual number could be far higher, but we'll never know, because—you guessed it—it's a national security secret. "There is no requirement that the FBI demonstrate a need for such records. It need only assert that the records are 'sought for' an intelligence or terrorism investigation," according to a 2003 statement on the Senate floor by Sen. Patrick Leahy—ranking Democratic member of the increasingly anachronistic "Senate Subcommittee on Constitution, Federalism and Property Rights". The National Security Letter existed and was used sparingly to track mostly illegal financial transactions before the PATRIOT Act transformed it into the default tool for collecting information on American citizens. The FBI could circumvent a warrant by using an NSL, but it had to provide specific facts to support its request (not that anyone except the recipient of the letter would actually see these facts).

Well, yes, it does. But the Supreme Court ruled during the 1970s that this right does not include protection of information provided to businesses. So as soon as you voluntarily disclose information to a business—a virtually unavoidable action—it becomes fair game for a warrantless search. In other words, if they don't kick in your actual door or tap your actual phone, pretty much everything else is fair game. That was bad enough to start with. Then the PATRIOT Act offered the FBI wide latitude to go after banks and credit card companies to obtain information without even bothering to provide a factual basis for its request—a factual basis which, you will recall, was not subject to outside verification or oversight. Instead of having to produce a pretext—however flimsy—for its seizure of financial records, the FBI could now simply assert the request had something to do with terrorism and go to town. Even that wasn't enough power, however, to suit the "new normal" in Washington. So the PATRIOT Act was amended and expanded to allow the FBI to send NSLs to virtually any kind of business or institution—"car dealers, pawn brokers, travel and real estate agents", according to Leahy. And so much more. The Act states that the FBI may demand "production of any tangible things (including books, records, papers, documents, and other items) for an investigation to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities" from an ever-broadening spectrum of business types.

Despite their barking protests, Congressional Democrats have been willing to bite and filibuster additional PATRIOT amendments that have expanded the NSL's reach still further since PATRIOT's 2001 debut. Businesses from self-storage to manufacturing were now potentially facing the risk of the secret letter, the ungentle demand for information and the outright threat of criminal prosecution if they breathed a word of this to anyone. The ACLU finally decided to tackle the issue head-on, filing a lawsuit on behalf of four librarians served with NSLs in the seething terrorism hotbed of Connecticut. In addition to a demand for patron records, all four were told they would go to jail if they discussed the NSLs with anyone, and that the duration of this gag order was forever and ever, world without end, amen. It was barely clear from the PATRIOT Act that they even had the right to contact an attorney. As the judicial tide began to shift in favor of the librarians, the Justice Department moved to implement what has lately become its legal strategy of first resort:

The idea here is to prevent the law from being declared unconstitutional and to force every potential future plaintiff to take the time and trouble of litigating their complaint in next week's exciting episode of "Stall, Bargain and Moot". But that isn't the only goal. While this process was playing out in the Connecticut case, you see, the PATRIOT Act was coming up for renewal. The librarians—understandably—wanted very much to speak out about this pending vote, but the government employed every legal tactic in its arsenal to keep them quiet until after the Act was renewed. Meanwhile, the law was subtly changed to disarm some of the plaintiff's best legal arguments (most notably by conceding explicitly that recipients of NSLs could talk to a lawyer before complying). The librarians finally won a fairly Pyrrhic victory in which the perpetual gag order was decreed "probably" unconstitutional, while the Justice Department dropped its efforts to enforce the order against them specifically once the PATRIOT Act was renewed for years to come. Many provisions were made permanent. Section 215—the NSL proviso—was not, but it was extended four more years. As one of the plaintiffs told the New York Times after the May 2006 decision, the victory felt "like being allowed to call the Fire Department after the building has burned down". Bloodied but unbowed, the Bush Administration continues to use NSLs to "fight terrorism". For instance, they've been particularly aggressive in using the letters to go after those dangerous extremists in the U.S. news media who don't toe the party line. Around the same time that the librarians were celebrating their righteous victory, an anonymous source contacted ABC News to inform its investigative reporters that the federal government knew who they were calling—and not just ABC reporters, but reporters for the New York Times and the Washington Post as well. Needless to say, there would be quite a stink if the FBI had to go through the courts seeking warrants for the phone records of mainstream news reporters covering government misconduct. But that's what the NSLs are for! ABC reported—and the FBI carefully non-denied—that an investigation of alleged CIA leaks was being facilitated by the use of NSLs and that journalists' phone records were most definitely not exempt.

A slew of nondenial-denials, half-admissions and weird obsfuscations followed. No one denied the NSA had the phone numbers. Yet the NSA was specifically exempted in the PATRIOT Act from using NSLs to collect whatever data it damn well pleases. So how did the agency convince all those phone and Internet companies to cough up their data? USA Today claimed they made arrangements directly with the companies. But the two companies that were willing to comment on the story denied that.

"One of the most glaring and repeated falsehoods in the media reporting is the assertion that, in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, Verizon was approached by NSA and entered into an arrangement to provide the NSA with data from its customers' domestic calls." Interesting choice of words there. What about BellSouth? The company issued the following:

"As a result of media reports that BellSouth provided massive amounts of customer calling information under a contract with the NSA, the Company conducted an internal review to determine the facts. Based on our review to date, we have confirmed no such contract exists and we have not provided bulk customer calling records to the NSA." Let's go back to Leahy's statement to the Senate. We'll pick it up mid-speech as he's enumerating the many things that the PATRIOT Act neglected to regulate when granting this considerable power to the FBI:

"Nor are there sufficient limits on what the FBI may do with the records or how it must store them. For example, information obtained through NSLs may be stored electronically and used for large-scale data mining operations." So let's walk through this. The NSA wants all these phone records, but it can't ask for them. The FBI can demand the records and threaten the companies with prosecution if they tell anyone that the bureau ever asked for anything. And once FBI has the records, it can do whatever it wants with them.

"[T]he intelligence activities I authorized are lawful and have been briefed to appropriate members of Congress, both Republican and Democrat." The gaping holes in the NSL law clearly allow for the possibility, and maybe even the "lawful" possibility. If the companies had received NSLs, they would be legally prohibited from saying so. For the moment, the question of whether it happened this way must remain unanswered. But really, this is just one of so many, many, many Big Brother scenarios that could play out in the wide open spaces surrounding the FBI's use of material seized through this mechanism. Use your imagination. It's a conspiracy theorist's delight, or it would be, except once they finish analyzing your Web-browsing, Amazon-reading, phone-calling, library-borrowing patterns, it's off to the gulag before you even get the chance to say "I told you so".

|

Now you might be wondering, doesn't the Fourth Amendment state that "the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized"?

Now you might be wondering, doesn't the Fourth Amendment state that "the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized"?  The most common uses—that we know of—include snatching customer data from Internet service providers of every ilk, the numbers and dates of subscriber phone calls and library records, because as everyone knows, what you read could be hazardous to the country's health.

The most common uses—that we know of—include snatching customer data from Internet service providers of every ilk, the numbers and dates of subscriber phone calls and library records, because as everyone knows, what you read could be hazardous to the country's health.  Oh, and remember that big NSA phone database that had everyone so upset? In May 2006, USA Today reported "The National Security Agency has been secretly collecting the phone call records of tens of millions of Americans, using data provided by AT&T, Verizon and BellSouth."

Oh, and remember that big NSA phone database that had everyone so upset? In May 2006, USA Today reported "The National Security Agency has been secretly collecting the phone call records of tens of millions of Americans, using data provided by AT&T, Verizon and BellSouth."  Could these be signs of a legal end-run using the NSLs as cover? Let's go the President.

Could these be signs of a legal end-run using the NSLs as cover? Let's go the President.