No single device has done so little good and caused so much annoyance as the car alarm. Before we turn to just how ineffective that blaring bit of ersatz security is (and how effective other forms of anti-theft devices are), let's examine first how this invention went awry.

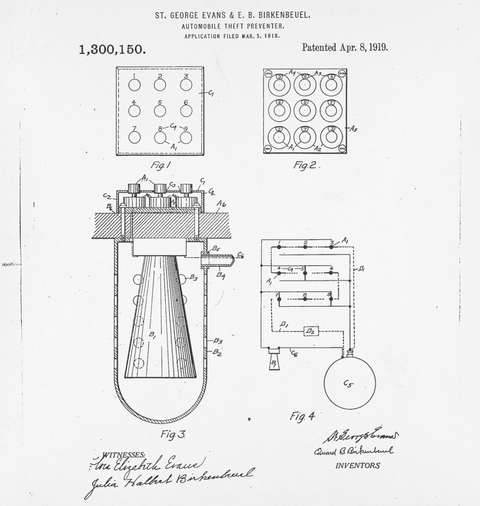

The approach of attention-as-deterrent dates back to 1918, when St. George Evans and E. B. Birkenbeuel of Oregon patented a device that would, "automatically signal an attempt to move an automobile by unauthorized persons." It was pretty clever for that time—start the car without entering the correct three-digit code combination and electricity is diverted to the horn. Maybe that was a good idea if you had the only car in the neighborhood, but almost a century later, when nearly everyone has one, it's collective masochism.

Noise as a solution makes sense, in theory: No thief wants attention, so make something that'll draw lots of it. Problem is, we (police included) have become desensitized. We know how easy it is to accidentally trigger the those horrific whines and screeches —a heavy truck rumbling by, a motorcycle that's had the baffles removed (another issue on its own), or just someone accidentally brushing against the side of the car while walking by. Even if the alarm is triggered during an honest-to-God break-in, what exactly are good Samaritans supposed to do? If anyone has ever rushed into the street at the sound of every car alarm, ready to go full vigilante on some ne'er-do-well shattering a window, I want to meet that person. In the city, a guy conspicuously stealing a bicycle doesn't even get a second glance—how is a someone quickly smashing a window and running off supposed to rate?

So in the car alarm, we have a device that's both ineffective and annoying. It's also unneeded: it's nearly impossible to start a modern car without the key. If anyone wants to steal a car nowadays, says Robert Sinclair of AAA, "they're going to have to bring a truck."

Starting in 1996, auto manufacturers were required to equip vehicles with OBD-II, a computerized engine diagnostics system that links the engine systems in a car (it's that port to the left of the steering column where mechanics plug in to asses car issues). That's when cars went from having flat metal keys to the keys with RFID immobilizers. No longer could you go to a hardware store to duplicate a key, and hot-wiring didn't work like the movies. Car theft rates have been since declining ever since, going from about 1.6 million annual incidents in the 1990s to around 800,000 in 2014, according to the National Insurance Crime Bureau, which analyzes crime like break-ins and grand theft auto.

There is, perhaps, one saving grace for car alarms: As our cars have evolved into a storage locker for our tablets, laptops, and Bluetooth paraphernalia, the alarm is also meant to guard against smash-and-grab break-ins. Car alarm proponents also say the device can stop thieves from taking wheels and tires. But, as Roger Morris at the National Insurance Crime Bureau explained to me, guys will "break in, roll the car to a vacant lot, and strip it for parts. Breaking into cars is a billion-dollar business."

Therein lies the rub. Break-ins are the problem. No one's driving away with these things unless the car is over 25 years old, or if the owner leaves the keys in the car (which does happen—there were 46,000 incidents of that last year, and that's just the owners who admitted to it). I drive everywhere with a $450 Valentine One radar detector, so even locking it in the glove box makes me nervous, especially when you hear that it's not hard to hack modern cars. Here's to hoping that gets fixed pronto. Until then, I avoid using my car as a storage space as much as I can. That, and I order a lot of Seamless.

I asked automakers how the alarms on their 2016 models work. Generally, the only way they trigger is if the car has been locked and the doors are opened from the inside—that is, if someone breaks the window and opens the door from the inside handle, then it'll sound. That's a big change from cars a few years back. Davis Adams, who works at Honda and drives an S2000, told me about a Lotus Elise he used to own that had a motion sensor. "If you locked the door, and moved your hand in the open air," he said, "the alarm would go off. So if you left a dog in the car, or someone leaned in the open convertible to look, it'd trigger the alarm."

If you've been hearing fewer errant car alarms lately, there's a reason. Back in the early 2000s, advocacy groups took legal action to make alarms less sensitive and quieter. Manufacturers have since, it seems, taken heed. "My impression is that there are far fewer false alarms now, and that this started around that same time, when the [New York] City Council held some hearings on the issue," says Professor Mateo Taussig-Rubbo of SUNY Buffalo Law School. He authored a 2003 paper called The Case for Banning Car Alarms in New York City. "I would speculate that the industry, especially the aftermarket sector, which may have had more problems, made the alarms less sensitive in order to get out ahead of any potential legislation," he says. Mercifully, that seems to be correct, (though you can still find it in some cars like the 2015 Escalade).

No one steals radios anymore, and cars have gotten impossible to steal (except via sophisticated hacking), which brings us to a wonderfully evolved era where, it seems, we've stifled some noise pollution, and gotten rid of something that doesn't work. Now, if only we can get ambulances and fire trucks to be less deafening.

Need to know the biggest scientific breakthroughs in our galaxy?

Get our newsletter for most fascinating space insights.

You're going to better understand our universe!

Thanks for joining us!