chapter

1

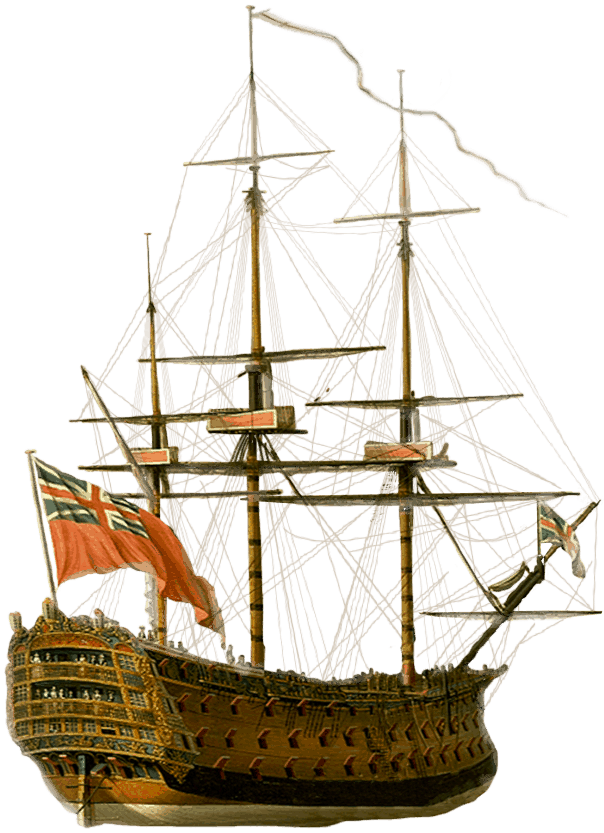

On the morning of August 29, 1782,

the HMS Royal George,

a colossal warship of five decks and 108 guns,

was anchored just off

Portsmouth Harbor at Spithead,

a favored rendezvous for the British fleet.

It was 9 am, a blustery morning, and the deck was a flurry of activity as ships arrived from shore to provision the vessel for a voyage to the Mediterranean. Its mission was to break the French and Spanish blockade of the vital British garrison on Gibraltar. The Crown was fighting a war on two fronts, against ancient rivals in Europe and its rebellious American colonies across the Atlantic. The Royal George could prove decisive. With its speed and complement of cannons, the ship was one of the most fearsome weapons in Britain’s navy. A veteran of many wars, the Royal George rose tall among the fleet, an oak leviathan festooned with acres of sails, the ship’s brass gleaming in the daylight.

In choppy waters, a delivery boat filled with casks of rum pulled alongside the Royal George. On board, wives visited husbands, children said goodbye to fathers, and merchants sold cheap trinkets and watches to the crewmen. Mingling with the sailors were “Spithead nymphs,” women who earned their living servicing men among the berths. On the gun decks, a group of sailors rolled 50 cannons to the centerline to help the vessel heel over, easing the delivery of the rum casks.

But the Royal George failed to hold steady, and the heel steepened. Lieutenant Philip Charles Durham, the officer of the watch, realized that his crew had failed to shut the gunports, now submerged, and the ship was rapidly taking on water. He ordered all hands to run the guns back to their original positions, but it was too late. The sea poured in and the ship was tipped onto its side.

Below decks chaos broke out. Cannons came loose from their lashings, careening down the sloping deck and crushing hundreds of sailors. Visitors and crew were trapped by torrents of chilly seawater rushing through the berths and passages. The ship’s towering masts crashed down onto the rum delivery boat, carving it in half. Those still on the top deck panicked; sailors, women, and children leaped into the water, only to be caught up in the ship’s tangled rigging.

The gunwales disappeared beneath the foaming waves, followed by the top deck, then the forecastle, until the entire ship sank beneath the swell of the sea and settled upright on the seabed 80 feet below. After 10 minutes, only the mast tips remained visible, like fingers grasping for the surface. The events of that morning became one of the worst maritime disasters in British naval history, with more than 900 sailors and civilians lost.

But the Royal George did not disappear from the minds of English mariners, even when settled on the seafloor. Everyone knew that the ship contained a vast fortune—the equivalent of $2.8 million worth of guns, timber, rum, and brass machinery—sitting in silt, just 80 feet from the surface. But in the era before the invention of diving technology, descending to those depths carried the risk of death. Yet the treasure that sank with the lost Royal George continued to beckon, seducing men who were desperate to change the circumstances of their lives.

chapter

2

Charles and John Deane, brothers born four years apart, grew up in a foul dockyard precinct on the edge of London. A former fishing settlement on the Thames, the area had been swallowed by Europe’s largest city. By 1800, it had become a squalid reach of maritime activity and drinking establishments overlooking a fetid waterfront. Locals called the area Deptford Green, but there was nothing green about the landscape of shipyards, slaughterhouses, and candle factories that stained the masonry black. Among the slum’s infamies was the tavern where Christopher Marlowe, one of England’s greatest playwrights, was said to have been stabbed to death in 1593.

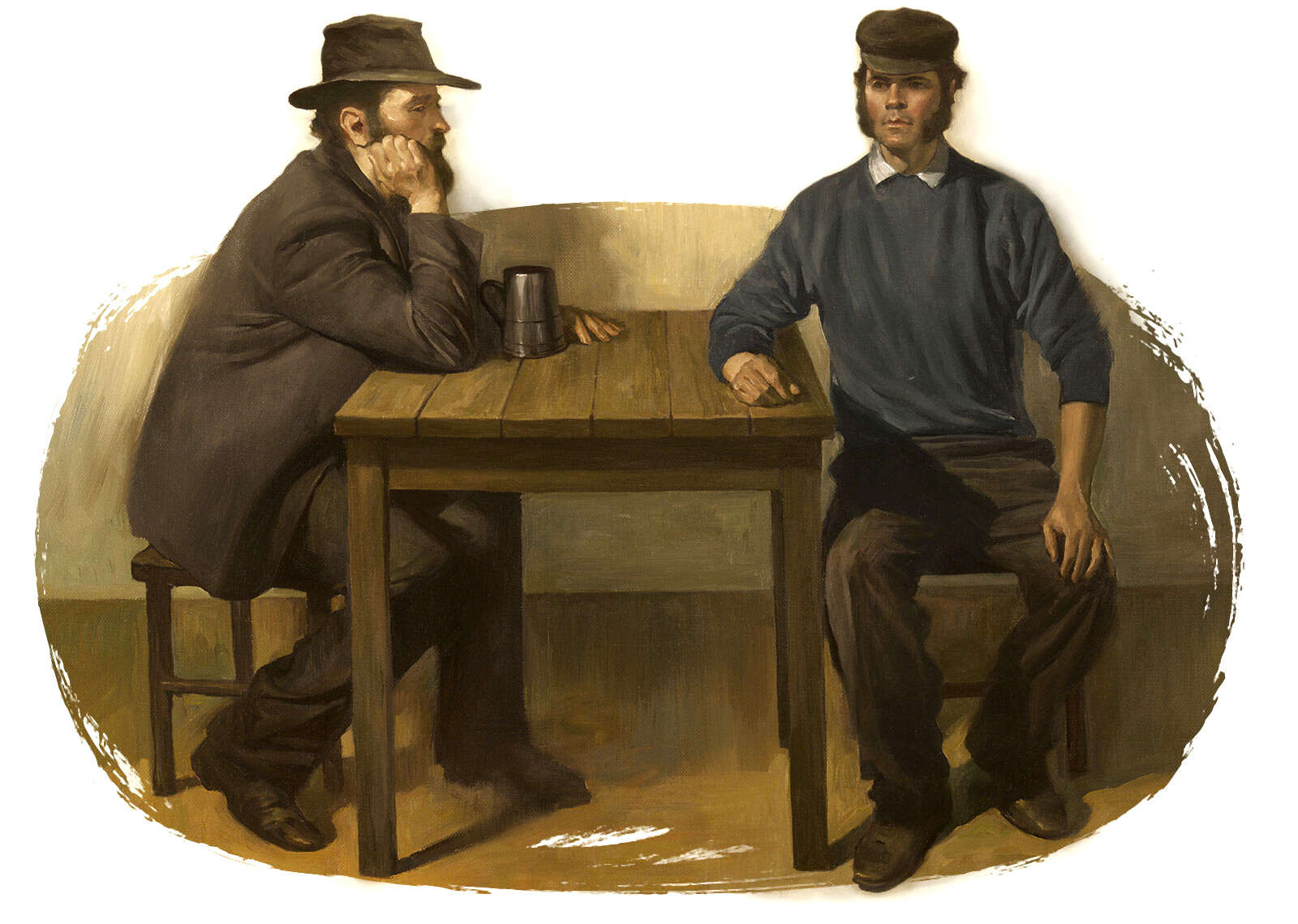

Charles and John Deane lived in poverty

on the outskirts of London.

It was ironic that the Deane family ended up living in a slum along the shores of England’s largest shipyard. A century earlier, their great-great-grandfather Sir Anthony Deane had been one of the world’s most renowned naval architects. He had spearheaded the construction of the British navy during the reign of Charles II and wrote Deane’s Doctrine of Naval Architecture, 1670, one of the earliest and most influential books on hydrodynamics. His portrait hangs in London’s National Maritime Museum. It was Sir Anthony’s navy that gave Britain unrivaled control of the seas, edging out other European powers. One of Sir Anthony’s 16 children, John, solidified the family’s fame when he was hired by Peter the Great to construct the Russian navy.

But the Deanes’ royal titles and estates had long since been squandered by the time Charles and John were born; their father toiled as a caulker, patching seams in the hulls of ships that his forebears once designed. When the brothers were boys, they were enrolled by their parents as “objects of charity” at the Royal Hospital School. They received a subsidized education, but in return they had to spend seven years as low-paid mariners. The school sought to prepare its charges for the harsh life that awaited them. The 700 students wore naval uniforms and were taught to march in unison. Charles, the older brother, shipped out in 1810 on a merchant vessel at 14 years old. Three years later, John was picked for a plum assignment as a captain’s servant. Charles and John served on many vessels, eventually sailing together to Madras, Bombay, and Macau—all difficult voyages, long months of tilting horizons while en route to distant points in the sprawling British Empire.

During the Deane brothers’ years in the merchant marine, they experienced the enormous hardships of life at sea, crammed together with hundreds of other men, poorly provisioned and tossed by waves. They survived disease and disaster; they saw men receive 300 lashes and witnessed others buried at sea. And, like many poor hands returning home to England and sailing past Portsmouth and the Royal George, they fantasized about the riches below.

In the previous decades, many daring divers had attempted to retrieve sunken treasure in a variety of contraptions—wooden containers, copper jackets, metal canisters. Some died. Others were crippled. One of the men who attempted to reach the Royal George was William Tracey, a successful ship owner who dreamed of even more wealth and constructed a formfitting diving suit out of copper with holes for his extremities and a hose to deliver air from the surface. But when he sailed into Spithead in 1782 and took his suit into the sea, he lasted only a few minutes before resurfacing. “The pressure of the water occasioned my great injury, as it was from that pressure I am now a cripple,” wrote Tracey, who lost all of his money after the misadventure and ended up in Fleet Prison, a grim debtors’ prison in London.

Yet the wreck of the Royal George remained a tantalizing prize, preserved and nearly undisturbed since the day it sank. So it was with all shipwrecks, not just in England but around the world. Since ships first sailed, countless vessels had gone to the bottom, where they remained out of reach. Throughout history, humans were limited to the surface of the sea—and feared the deep. The underwater world was regarded with superstition, a mysterious place where monsters dwelled. Every shoreline marked entry to this immense unconquered frontier, beckoning adventurous souls and, by the early 19th century, clever engineers. They were drawn by the thrill of exploration and the allure of instant fortunes—thousands of years of wealth lost beneath the waves.

To 19th century mariners, the sea was a mysterious

realm inhabited by monsters.

chapter

3

After the Deane brothers fulfilled their service as merchant marines, Charles found himself back in Deptford, living just down a dirt road from his childhood home. At 29, Charles was moody, well-worn, and complicated—a loner who had trouble getting work. He struggled to provide for his three children and eventually took a lowly job patching ships’ seams alongside his father.

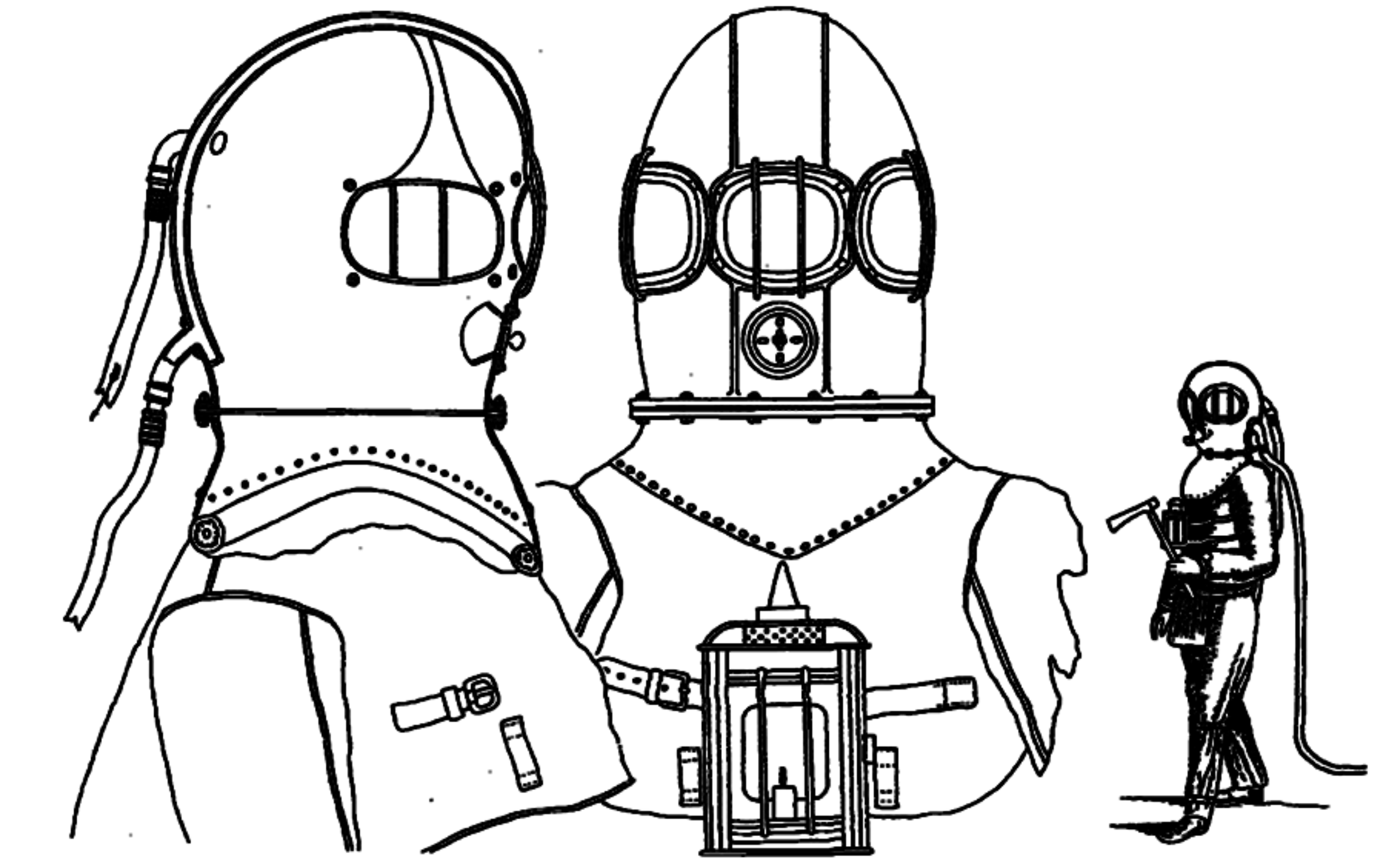

Desperate to find a way out of poverty, he began sketching an extraordinary new device that would make him rich. Like his ancestors, Charles had a passion and talent for engineering, and he knew that the greatest danger to ships at sea was not water but fire. So he devised an “Apparatus to extinguish Fire in its origin”—a copper helmet riveted to a leather or canvas jacket and fitted with a hose that delivered fresh air from a pump. On his patent application, Charles described his helmet as a

“Machine to be Worn by Persons Entering Rooms or

other Places filled with Smoke or other Vapour,

for the Purpose of Extinguishing Fire or Extricating

Persons or Property therein.”

Charles Deane dreamed up the idea of a smoke

helmet for firefighters in 1823.

The idea was promising enough that Charles was able to persuade his employer at the shipyard to invest 417 pounds in the project, the equivalent of about $47,000 today. While still working full-time at the shipyard, he spent a couple years perfecting his invention, commissioning four prototypes. It was the height of the Industrial Revolution, whose mechanized wonders and technological innovations were transforming England and making men wealthy. Charles was sure that his smoke helmet would propel him into their ranks. He gave demonstrations wherever he could, but Charles was not a salesman and could not find a market for his invention. Frustrated, he tossed the helmets onto a shelf at the shipyard, where they sat for months, ignored and practically forgotten.

Unlike Charles, John was gregarious, made friends easily, and excelled at his work. For several years, he had been largely supporting his older brother. When John received a plum position aboard an East India ship, he convinced the captain to hire Charles. When Charles needed money, John provided it. During their difficult moments—in the harsh naval school, during their hard times in Deptford—John offered cheerful words when Charles was low.

While Charles toiled in Deptford, John lived 60 miles southeast in an oyster-harvesting village called Whitstable and worked as a “sweeper,” employed by a salvage company that trolled for lost anchors and other valuables on the shallow seafloor. Sweeping paid modestly, but it was reliable work and offered the promise of discovery. One day, John and his crew would pull up a downed bale of cotton or salvage lumber; the next, a brass gun or crate of barnacled brandy.

But salvage methods were extremely limited. For centuries, the leading technique for recovering sunken goods was to hold one’s breath. It was hardly an efficient technique. In the 1500s, a great leap forward occurred when an Italian named Guglielmo de Lorena invented the diving bell, an upside-down wooden pot that held a bubble of air. De Lorena wore it over his head and was able to explore Roman barges sunk in Lake Nemi. In 1691, the British astronomer Edmond Halley—who investigated the cyclical comet that bears his name—improved on the idea by installing a window and was able to replenish the air supply by lowering barrels of air to the bell.

But the diving bell was an extremely cumbersome way to explore the ocean. The bells of the 18th and 19th centuries were made of thick metal and therefore difficult to move. Nevertheless, amateur mariners tried to use them for reaching treasures like the Royal George. The British papers regularly told tales of ingenious contraptions and disastrous dives. In 1782, a Scottish candymaker named Charles Spalding used a bell of his own design to descend to the famous ship. But visibility was poor, and he was only able to gather a few small objects from the wreck.

Eight months after visiting the Royal George, Spalding and his nephew used their bell to explore a wreck off the coast of Dublin. By the time they resurfaced an hour later, the two were dead. A subsequent inquest could not determine a cause of death, and their fate was similar to that of many would-be divers of the time, as men descended in “diving dress” of their own design and drowned or floated back to the surface with various gruesome maladies.

Most of the injuries were a function of pressure, a phenomenon poorly understood at the time. Those in watertight diving suits connected with air hoses suffered from the worst injury, a condition called squeeze.

In the shallower depths, diving seemed fine at first. Ten feet down, no problem. Twenty feet. Still fine. But at around 30 feet, they would feel pressure mount around the soft tissues of their face and neck. They’d try to breathe, but there’d be no air. At 40 feet, their face would engorge with blood. The blood vessels in their eyes would burst and bodily fluids would shoot from their orifices. Then they would hear a sickening swish at the back of the dive helmet—this was the sound of their hair being sucked off their scalp. At extreme depths, their face would rip from their head and be deposited back through the air hose on deck in a bloody spurt.

The Royal George sat in waters about 80 feet deep. At that depth, a pressure differential could create suction 10 times stronger than a modern vacuum cleaner. That might not be strong enough to rip off a face and suck it through an air hose, but it would certainly cause permanent damage or death, as was the sad fate of William Tracey and many others that came after him.

Yet these dangers were no deterrent. By 1825 modern mechanics was reshaping every field, including maritime exploration, allowing more men to take chances in the depths. That year, an inventor named William James patented a diving helmet rig, complete with an onboard air supply—an idea that wouldn’t be practical for another century, when scuba gear appeared. At about the same time, the first tunnel under the Thames began to leak and an enterprising young engineer used a diving bell to explore the damaged area. The press covered the investigation closely.

Amid all this diving interest, the Deane brothers had a flash of inspiration: Perhaps Charles’ smoke helmet could be repurposed to allow a man to breathe underwater. And if that was possible, maybe they could use it to descend those deadly 80 feet to the Royal George. Unlike the diving bell, their helmet would allow free movement underwater, and they’d be able to pull riches from the wreck.

This idea took shape just as Charles was facing a bleak future. After the Napoleonic Wars, the demand for battleships had waned and the Deptford shipyards were in decline. The local docks were shuttering because the Thames was filling up with silt, making it unnavigable for large ships. Soon, Charles would be out of work. If he didn’t figure out another means of support, he’d risk landing in debtors’ prison. Since being held (and often tortured) in a cell made it difficult to repay one’s obligations, debtors’ prison was a trap from which it could take decades to escape. The deep sea was a dangerous realm, but the Deanes had always found their living on the water. It was a risk the brothers decided they must take.

chapter

4

chapter

4

On a breezy day in 1828, Charles and John stood along a section of the Croydon Canal, a silted-in waterway once used by barge traffic through London. Pedestrians on a nearby footbridge formed a curious crowd as Charles assembled his equipment. He fitted his shoulders with canvas and seated his metal smoke helmet over his head. The brothers had spent weeks adapting the helmet for aquatic use, and here in the canal they would test their new engineering. Charles shuffled toward the channel, tethered by a leather hose to John, who stood onshore and began to pump a hand-powered billows that fed air into his brother’s helmet.

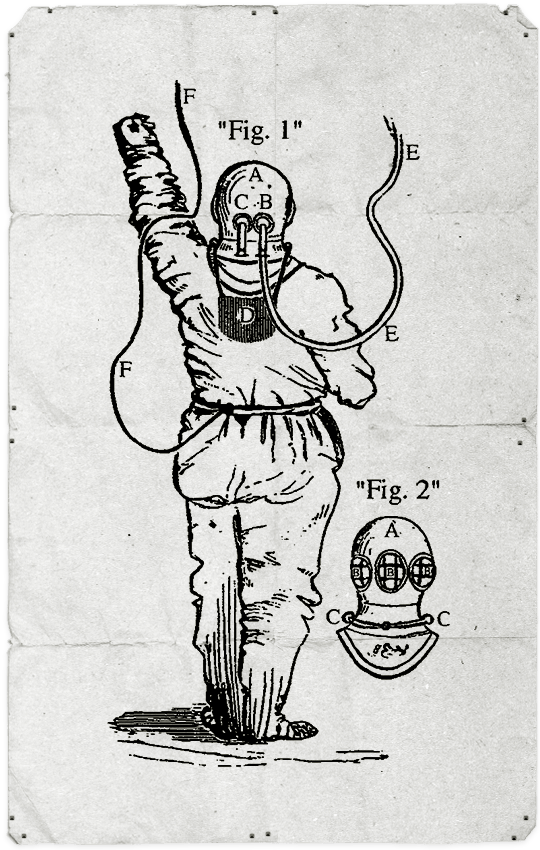

In 1828, the Deanes modified a smoke helmet to

serve as an underwater breathing apparatus.

Charles waded into the canal, his feet settling into the muck. Step by step he advanced, until the water rose to his knees, then to his shoulders. He took a deep breath and another step and finally disappeared, leaving only an oily wreath at the surface.

John’s hands, firmly joined around the pump handle, drove air into the helmet. For a moment, the water boiled with bubbles. But Charles quickly bobbed back to the surface. The air trapped in his helmet and in his clothes made him too buoyant. He tried to submerge again but leaned too far forward and the helmet filled with water, leaving Charles sputtering for air as he flung off the contraption. The brothers were learning hydrodynamics by trial and error, and the crowd got a good show.

It was a rough start, but Charles understood the flaws in his initial design and came away convinced that he and John could make the converted smoke helmet seaworthy. Over the next few months the brothers systematically solved a series of technical problems, returning again and again to the Croydon Canal to test their modifications. The Deanes even hired a Scottish chemist named Charles Mackintosh to fabricate a diving suit out of rubberized cloth—a precursor to the modern wet suit and the first submarine use of the now-famous Mackintosh slicker. Then John put up the money to hire a German engineer named Augustus Siebe to manufacture an improved helmet that would be robust enough for a true dive, one deep enough to get them to the Royal George.

By 1842, the Deanes had refined their diving outfit.

The Deane brothers intuited that pressure was the key to survival underwater. They built a powerful hand pump that would create enough air pressure to keep the helmet from flooding. And they left the bottom of the helmet open to the water, like a miniature diving bell, which alleviated the danger of a sudden lethal vacuum. If things went wrong—a ruptured hose or jammed pump—the Deane helmet wouldn't “squeeze” the face from the head of its occupant; instead, the helmet would just fill with water. The diver could swim back to the surface, fix the problem, and resume diving.

With all of these modifications in place, the brothers returned to the water for a final test—this time in the Thames, just upriver from Deptford. Charles descended a ladder from a barge with confidence and disappeared below the surface.

A crowd watched from shore. A minute passed. Then another. A froth of bubbles rose from the murk. John tended his station at the pump. After a few more minutes, Charles had been below the surface longer than a man could hold his breath. Either he was dead or the improvements to the Deane helmet were working.

John and the crowd awaited a sign of Charles’ fate, and then they got one: Charles’ hand pierced the surface and grabbed the ladder. He hauled himself up, rung by rung, as the water streamed in rivulets from his soaked suit. It was as if the crowd had witnessed a resurrection. Charles had just walked underwater, free to explore the depths. And he had returned to the surface unharmed.

But if the Deane brothers were ever going to escape their lives of poverty, they would need to take the helmet into deeper waters, to redeem sunken treasure from the sea. And there was no more coveted treasure in England than the Royal George.

chapter

5

Charles and John Deane, along with a small crew, gathered on the deck of a boat owned by John and readied their equipment. Eighty feet below lay the Royal George and $2.8 million worth of cargo and matériel. It was October 29, 1834, and the Deane brothers were sure that their diving suit was ready for the challenge of reaching the lost battleship. John stood behind Charles and lashed rope into a seal around his brother’s wrists. For insulation, Charles wore an underwear ensemble that included a wicker corset, layers of wool frocks, long johns, and a red wool cap. (The cap would later be adopted and made famous by French marine explorer Jacques Cousteau.)

John fixed a safety line around Charles’ leather waist belt, and the crew strapped on 80 pounds of lead for quick descent. Then Charles shuffled to the gunwale, where John carefully placed a gleaming copper helmet over his brother’s head.

Through three fist-sized windows in the face of the helmet, Charles watched the rope ladder unravel into the darkness below, a staircase to a netherworld. John took stock of his brother through the helmet’s windows. Inside, Charles was breathing steadily.

Both brothers knew that any misstep could be lethal. This was no rehearsal in the Croydon Canal. Charles’ destination was 12 fathoms deep in the open ocean, with currents, sharks, and the jagged remains of a warship. John was concerned for his older brother, but since Charles was willing to bet his life on the soundness of his invention, John would back him. Charles gripped the ladder, and began to climb clumsily down into the chop, disappearing slowly like a man fading into London fog.

Minutes passed. John paid out rope and hose. The deckhands cranked the air pump faster. The only sign of Charles was the periodic ripple of bubbles filtering up from below. John knew that the deeper Charles dived, the larger those bubbles would grow as the air exhaled from the helmet expanded on its way to the surface. When the roil of bubbles beside the ship doubled in size, John knew Charles had gone past 30 feet.

John released more rope and the crew doubled the action at the pump. Sixty feet. Seventy feet. At 80 feet, the rope stopped unwinding. John gave a tug and waited for Charles to return the sign. The brothers had agreed on a simple code. One tug from above meant “Are you OK?” One from below answered yes. Two tugs from Charles was a request to pay out more rope. Three tugs signaled that valuable salvage was ready to be hoisted to the surface. And constant tugging was an SOS, an emergency call to be pulled up immediately. Following John’s query down the line, there was nothing. Another moment, noresponse. Then, after a pause that felt endless, John sensed one single, solid tug.

chapter

6

chapter

6

The rope ladder reached bottom and Charles jumped from the rungs into a strange world. Here the light was a relic of the surface, stripped of warm hues and dimmed by refraction into a deep blue-green gloom. Charles could see his hands, but they seemed out of focus, almost fake. Standing in near-darkness, he squinted through the heavy glass in his helmet and observed wooden planks between the seagrass. He was standing on the deck of the Royal George.

Charles was delighted but wary. The wreck sat askew on the seafloor; its three giant masts were set at an angle, the tips receding into the distance. He had to be careful. He could now see that the deck was rotting and full of gaps. And the ancient rigging—miles of rope and tattered sailcloth rolling gently in the current—could easily snag his safety lines. Each step carried the possibility of being trapped in the wreck.

He took another deep breath and stepped away from the safety of the ladder. The deck timbers seemed to hold. Towering over Charles was the aft deck. The captain’s elegant stateroom sat inside, just past a set of decomposing doors.

The captain’s quarters were tempting, but Charles knew that the real treasure was below decks. It was an enormous risk, but he maneuvered the ladder until it fell into the belly of the wreck, then descended farther. The deck beams overhead shut out more light. He landed on a gun deck and let his eyes adjust. It was hard to see clearly, but something in the murk caught his attention; it was metallic, maybe cylindrical, and sizable. Charles moved slowly across the sloping, darkened footboards. When he reached the glinting object, he swept his hand over 50 years of sediment. Silt swirled around the glass windows of his helmet and revealed the dim but unmistakable hue of brass. He’d put his hand on an enormous cannon that would turn out to be worth about 600 pounds sterling, or nearly $75,000 today. This was more money than Charles could make in a year caulking ships. He surveyed his whereabouts. There were dozens more cannons scattered in every direction.

chapter

7

Back on the surface, John felt three quick tugs on the signal line. It was the message he’d been dreaming of for years: valuable salvage secured. John reeled in the slack of Charles’ rope and air hose as Charles ascended, moving quickly, from 60 to 50 to 40 feet. Still, John saw only bubbles—until he glimpsed movement below, a hazy gold shimmer that brightened and grew and eventually resolved into a ghostly figure slowly climbing the submerged rope ladder. The figure was accompanied by a garland of silver bubbles, swirling around what John knew to be Charles’ copper helmet, which still seemed almost distant when it suddenly burst through the surface.

Charles lurched up the ladder and onto the deck, and John helped pull off his helmet. When Charles caught his breath, he explained what he’d seen: the darkness, the ship, the fortune in cannons. A new era was dawning. That vast, impenetrable territory could now be seen through the glass of the Deanes’ helmet. Charles’ submerged steps on the rotting deck of the Royal George would eventually make all the Earth’s surface part of man’s domain, subject to exploration—and exploitation.

But for the moment, the Deanes were focused on recovering their booty below. It took hours for the brothers to haul that first cannon to the Portsmouth jetty, but the effort was worthwhile: The gun weighed 5,800 pounds, and it was in perfect condition, still loaded with shot.

Over several weeks, the brothers would take turns diving back down to the seafloor. They were able to recover an additional 23 cannons before the weather turned bad and forced them back to land. Altogether, the guns were worth approximately 10,000 pounds, roughly $1.25 million today.

And that was just the Royal George; the brothers immediately understood the broader financial implications of their jaunt off the shore of Portsmouth. They could soon move on to the centuries of wrecks around the British Isles, ships of all sizes and eras loaded with silver, jewels, gold bullion, and valuable artifacts—tens of millions of dollars, there for the taking. And Charles and John were, for the moment, the only people capable of reaching them with any consistency and safety. In an instant, they knew, their lives had been transformed. They were now wildly, ecstatically rich.

chapter

8

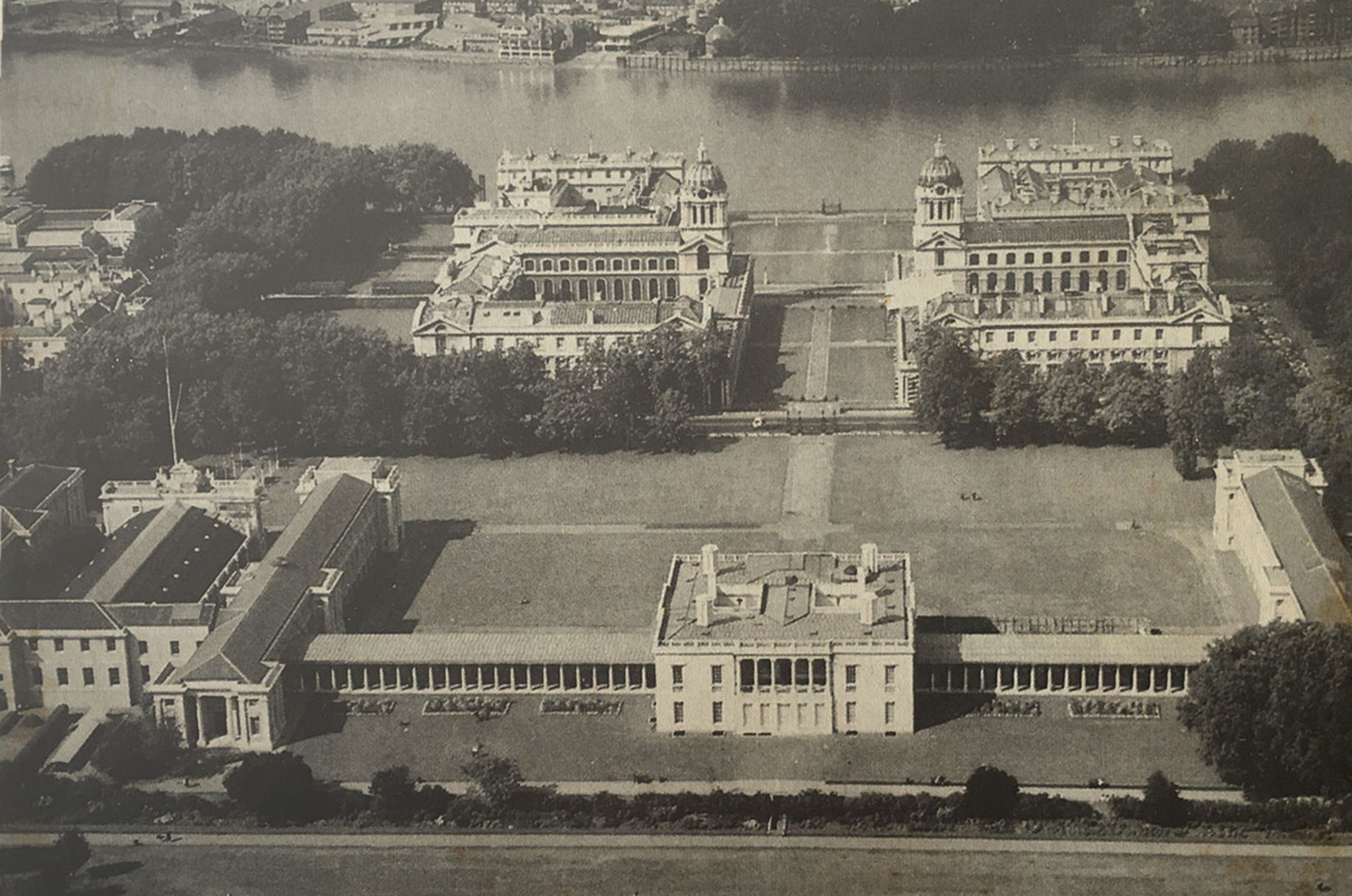

As winter set in and diving wrecks at sea became impossible, Charles chartered a boat and sailed up the Thames. It was just before Christmas—December 18, 1834—and he passed within miles of his old home in Deptford Green before anchoring in front of the Royal Hospital School. Almost three decades earlier, the Deane brothers had been objects of charity. Now fortunes had changed. Charles was returning to the scene of his impoverished childhood to demonstrate for his teachers, neighbors, and family how the young dreamer Deane had made something of himself.

The Royal Hospital School sits on the

banks of the Thames.

Children streamed from the school to witness Charles’ arrival as he rolled out one of the salvaged Royal George cannons—loaded with shot “as clean and perfect as the moment it came from the foundry,” wrote a local reporter—and lit the fuse. The 85-year-old weapon fired with a dramatic report. Later that day the bells of Deptford and Greenwich rang merry peals in Charles’ honor.

It was a hero’s homecoming, but an incomplete one. John was not in attendance. Charles had not invited his brother. In their days at the Royal Hospital School, the boys had been so close. Now, after their mutual triumph in engineering and discovery, they kept their distance from each other. Their success at sea summoned wealth from the depths, but along with it arose resentments that had been building for years.

Throughout their youth, John was the better student, rose higher through the ranks as a sailor, and had many friends. Charles was the man of ideas, but his diligent younger brother was the one getting noticed, the one who had found some measure of accomplishment. Their opposing traits, although complementary, wore into bitterness. Charles had needed his brother to complete the helmet—the invention reflected both of their personalities, equal parts practical and wildly inventive—but after so many years overshadowed by John, Charles wanted to claim credit for himself. John had by now dived in the helmet more than his brother, but Charles explained to all how the invention was solely his. When he came ashore to greet the crowds in front of the Royal Hospital, he talked about his journey to the bottom of the sea in his extraordinary new invention, but he never once mentioned his brother.

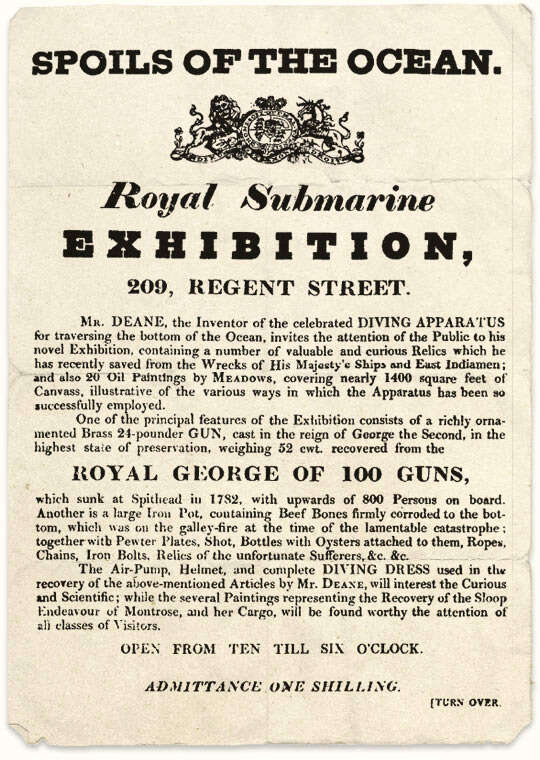

After decades living in John’s shadow, Charles wanted the spotlight for himself. He commissioned a series of oil paintings depicting his maritime triumphs and announced an elaborate exhibition at the Cosmorama, one of the West End’s most fashionable salons.

He titled the show Spoils of the Ocean and printed self-congratulatory posters heralding:

Mr. Deane, the inventor of the celebrated

diving apparatus for traversing the bottom

of the ocean, invites the attention of the public

to his novel exhibition.

For an admission price of one shilling, visitors could mingle with Charles and hear him recount his tales of adventure. He had filled the hall with a salvage menagerie of the Royal George’s guns, copper, and cannons. He even included an iron pot still filled with the beef bones set to stew when the battleship sank, and other “Relics of the unfortunate Sufferers.” Paintings of Charles exploring the wreck flanked the elaborate display, from which any depiction of John was notably absent.

Charles’ revisionism worked. Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post referred to him as

“this ingenious gentleman, whose

diving apparatus is so perfect

a nature that the bottom of the ocean

is with him as dry as land.”

The aged admiral Philip Durham, one of only two officers to survive the sinking of the Royal George, visited the exhibition and expressed “his approbation” and “good wishes for the success” of the show. Nautical Magazine published a glowing review. “Our readers have heard of Mr. Deane, and his extraordinary submarine operations on the Royal George,” the editors wrote, and went on to proclaim that

“the enterprising and truly national character of

[Charles’] labours will ensure him that cordial and generous support

from a British public which he so fully deserves.”

The London Times was similarly enthusiastic:

“The person to whom the government

and the public are indebted for the recovery

of these things is Mr. Deane.”

Charles was becoming a national hero.

The public grandstanding may have gratified Charles, but it also alerted the world to his methods. Now anyone could read in the newspaper about the Deane brothers’ exploits. Soon, three separate manufacturers began producing helmets strikingly similar to the Deanes’. Lloyd’s, the giant insurer, offered handsome commissions to anyone willing to reclaim valuables from sunken ships that it had insured. Enterprising sailors across the United Kingdom, and soon Europe, took up the challenge, sparking a 19th-century deep-sea gold rush. One of the first to produce a Deane helmet knockoff was Augustus Siebe, the former watchmaker who’d manufactured the original Deane smoke and diving helmets. In subsequent years, Siebe would build a brisk manufacturing trade around diving equipment, carrying his name into history despite Charles and John having given him the original design.

While Charles basked in public acclaim, John saw danger in the competition and set off on his own to beat rival divers. Over the next few years, he dived isolated sites in the North Sea and sailed farther south to dive the Duke of Marlborough, a sunken trading vessel with cargo valued at $3.5 million today. He learned how to use explosives to detonate ships half-buried in the mud, allowing them to offer up their bounty. He ventured along the west coast of Ireland and dived the Lady Charlotte, a large freight vessel driven ashore while sailing from Peru to Liverpool. In just a few weeks of diving, John recovered gold, dollars, and silver worth more than $11.2 million today.

While exploring near the Royal George, John discovered a ship whose cannons were engraved with a rose-and-mitre insignia and the words henricus vii, which identified it as the Mary Rose, a Tudor warship that sank in 1545 in defense of Henry VIII’s England against France. John began salvage operations and managed to pull up four more cannons.

The spectacular find eclipsed the brothers’ salvaging of the Royal George; this was not a ship from living memory—the Mary Rose had vanished centuries earlier, in an infamous naval battle. As the newspapers turned their attention to John and the Mary Rose, the focus on Charles faded, putting him once again in the shadow of his brother.

chapter

9

Eighteen thirty-six was a difficult year for Charles. His wife, Sophia, and his two youngest daughters—Royal Georginia and her younger sister, Jane, both still toddlers—died within a one-month period when typhus swept through London. Charles, now 40 years old, was devastated. His mind seemed scattered; his plans became erratic. When the Admiralty, which had authority over the Royal George, asked Charles to recover further salvage, his response was incoherent.

A wealthy Irishman met Charles on his travels and described some of his oddities. Charles appeared to be fascinated by marine flora and was “engaged in tearing away seaweed from the rocks on which he was walking.” Charles also liked to theorize about “the effect of the Drummond light in submarine illuminations, while observing the sun gleaming down through the water.”

Charles was likely suffering the effects of nitrogen poisoning. The Deane helmet, with its revolutionary open design, saved the brothers from squeeze and other injuries, but they did not realize that the greatest danger was invisible.

Pressurized air within the helmet was saturating Charles’ muscle tissues with nitrogen. When it was time to climb back to the surface, the nitrogen would expand and bubble into his bloodstream. With brief exposure, nitrogen bubbles might trigger headaches, vomiting, and numbness. After prolonged exposure from very deep and long dives, the bubbles could induce rashes, strokes, seizures, paralysis, insanity, and death. These ailments would later be dubbed “the bends,” because the condition doubled up victims in extreme pain.

Among the earliest generation of divers, dozens of men reported shattering pains of all kinds after long dives. Some vomited bloody foam, while others lost use of their limbs and began dying. “A sharp pain shot like lightning through my lower extremities,” wrote one helmet diver. “The next instant it went through my whole system, so prostrating me that I could not move a limb, or even a muscle…. The best physicians pronounced me incurable…. It was five tedious months before I could step; and in the spring I was only so far recovered as to walk a very little with crutches.”

Physicians of the era were ignorant of the cause and often did more harm than good, administering remedies like leeches or turpentine enemas. Some doctors recommended divers might take “some therapeutic Cognac” upon resurfacing, a stiff drink being a common treatment for misunderstood maladies.

Modern medicine would later learn how the absorption of nitrogen into the bloodstream could cause physical afflictions and permanent brain damage. The bends turn out to be a fickle illness. They can manifest among two physically similar divers in vastly different ways. Charles was arguably the oldest working helmet diver in the world; he’d spent countless hours diving deep and drinking heavily at taverns—factors making him more susceptible to the bends. John, who was younger, disciplined, and sober, would dive twice as often as Charles, to even greater depths—downward of 140 feet—and stay underwater for more than five hours at a time with never a single ailment. Even today, scientists can't predict the exact time or depth at which divers will suffer the bends. Sometimes it’s genetics; sometimes it’s dumb luck.

In the Deanes’ day, it was also unknown that nitrogen poisoning had a cumulative effect: The more time divers spent underwater and the deeper they went, the more nitrogen they would absorb. The Deane brothers had helped to open a new realm for humanity to roam, but a life beneath the surface could exact a terrible price. Over time, the bends could drive a man insane.

chapter

10

It was only four years after the successful dives on the Royal George that Charles’ ailing health forced him into a kind of retirement. Eventually his joints would ache so deeply that he walked with a cane. He spent his time brooding and carrying on about the many perceived maltreatments that chased away success. He rarely dived anymore and bemoaned the failure of his lawsuits against various competitors for patent infringement. His patent only covered the use of the suit as a “smoke helmet” and said nothing about diving. Charles was once again edging toward bankruptcy.

Near penniless and losing his grip on sanity, Charles announced in August 1838 that he would once again dive the Royal George, this time without John. If the wreck had made him rich and famous once, perhaps it could repeat the trick. This time he would lead a small crew and do all the diving himself, proving to all his own mettle without the aid of his brother.

He left London and took a cheap room near Portsmouth Harbor, a place notorious in England for disease and vice. At night, drunken sailors bartered with prostitutes and scavengers scooped horse and human waste from gutters to sell as fertilizer. By day, Charles dragged his broken body to the wharf and set sail for the Royal George. He arrived in position and plunged to the depths again, but this was a different ship than the one he’d seen years prior. John and other divers had salvaged all the easy pickings. Charles spent three arduous months diving alone, threshing through the broken ship, but there was only debris and ragged flax linen torn from the sails. As winter set in, Charles had salvaged nothing.

“I have become a great sufferer,” Charles wrote the Admiralty in a desperate plea for employment. Charles explained that he had hoped his diving apparatus “would prove a source of benefit to me after all my toils, but owing to the invention being copied and manufactured by many others … I do therefore most humbly submit my case in hopes your Lordships will be pleased to take my request into consideration in giving me an Appointment.” As in his youth, Charles required charity, but now there was none forthcoming.

The Admiralty had nothing for him, and Charles was left to wander the streets of London hunched over, his sanity unraveling. At times, he was still struck by the illuminations of an inventor’s mind, and he sketched out new ideas—a pneumatic subway, a rapid-fire cannon system, a waterborne vehicle that would have been a kind of precursor to the Jet Ski—but without John such things could never materialize. As Charles’ grasp on reality loosened, his family committed him for a time to the Peckham House Lunatic Asylum. When Charles’ son was asked on a school form to name his father’s profession, the boy wrote a single word: insain.

Broken and despondent, Charles was admitted to the

Peckham House Lunatic Asylum in 1839.

Whatever treatments Charles was offered by the asylum doctors over the years did little good. On the morning of November 7, 1848, Charles was living in London’s seedy Limehouse district. Over the previous few days, he had suffered delusions that unknown persons wanted to break into the house and carry him away. Charles rose from bed to get a glass of water. Then he opened a nightstand table to retrieve a straight razor. He had lived 52 years and spent most of them in struggle—with poverty, with his brother, with his own hardheadedness. He’d had a moment of glory and riches, but it was long since squandered. He had changed man’s relationship to the sea, yet had already been forgotten. Charles took the razor, drew it across his own neck, then fell back onto the bed and bled to death.

chapter

11

John was living in Whitstable when he learned that Charles had died. The London Morning Chronicle reported it under the headline

“suicide by the inventor of

the diving apparatus.”

“It appeared from the evidence that the deceased was by trade a caulker but did not follow his business and applied himself entirely to study and invention,” the article read. “The constant study had so affected his mind that he was twice confined to a lunatic asylum at Peckham.”

The brothers had been estranged for years but closely joined for much of their lives. They were reared in penury together, sailed the world together, invented together, and were rewarded with riches and fame together. They had revived the legacy of the Deanes as engineers and maritime icons, but that success had been clouded by madness, tragedy, and now the shame of suicide.

After so many years diving wrecks, John’s own family had come undone. His wife, Agnes, had long since died, in 1844. He’d been at sea when she passed, and his elder son had to sign the death certificate. Then, in the summer of 1852, John’s second son, Henry William, drowned while swimming in a London canal. With nobody else to care for them, John’s three daughters moved in with the family of Matthew Browning, John’s longtime friend and neighbor. When John returned to Whitstable, he too roomed in the Browning’s seaside cottage. It was a way to be close to his daughters, who had settled in comfortably with the Brownings.

The house was dimly lit and prone to flooding, but it had other, special charms for John, in particular Matthew’s pretty, young daughter, Sarah Ann. John was almost three decades older than Sarah, but it didn’t seem to matter. She was quickly taken with the worldly, wealthy adventurer and would sit quietly in the living room and listen as Matthew and John recounted their maritime exploits around the fire. Over time, John and Sarah grew closer. Sarah pitied John for the loss of his brother, wife, and son. She thought he needed caretaking and that she could give him comfort. Sarah was falling in love.

John could have married Sarah, of course. But for months he made no mention of matrimony. Instead they made the small, slow gestures of unspoken courtship between a middle-aged man and young woman in Victorian England, where intimacy smoldered at a distance.

Sarah Ann Browning was 29 years younger

than John Deane.

chapter

12

The knock came on October 16, 1854. John was at home when a messenger delivered a letter from Sir Baldwin Walker, an admiral in the Royal Navy. The Kingdom needed John’s help at sea. Across the globe, Britain was deeply mired in the Crimean War, a conflict that set Russia against Britain, along with its French and Ottoman allies. This was the era of the Pax Britannica, the rise of an empire on which “the sun never set”—a colonial domain stretching across six continents and ruled with 1,000 ships from the most powerful navy in the history of the world. But Russia had been rapidly expanding its own empire, challenging British naval supremacy in the Black Sea and eastern Mediterranean. For Britain, this was a matter of power and national pride. The symbolic image of Britannia was a woman holding a trident—a new master of the sea. Yet here was Russia, challenging her from Sevastopol, a city on the Crimean Peninsula where it had built the largest port on the Black Sea.

Franz A. Roubaud’s 1904 panoramic painting depicts the carnage of the Crimean War.

The Crimean War was a kind of dress rehearsal for the disastrous conflicts of the 20th century: technological, lethally efficient, intractable. At sea, the Russians had kept the British at bay with new weapons: cannons armed with exploding shells that set traditional wooden ships on fire; and the first underwater mines, deployed throughout the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. As a result, the war soon ground to a bloody stalemate, a disaster for all parties. By the time John received the admiral’s letter, more than 150,000 people had died—some 600,000 would perish over the three years of the war—and the main front would soon settle into a lengthy, dismal siege of Sevastopol.

This was the matter at hand in Admiral Walker’s dispatch to John. The British navy could not approach Sevastopol because the Russians had scuttled their entire Black Sea Fleet at the mouth of the harbor. The casualties could mount indefinitely unless they were able to clear the wreckage. The navy needed John to dive the line of wrecks and destroy them with explosive charges.

John was 54, twice the age of the average soldier. He had never dived with other people’s lives at stake. And the task itself was daunting: He would be asked to plunge into the Black Sea in winter in the middle of a war. He’d have to tangle with explosives while war raged at the surface. But he was England’s most experienced diver and subaquatic munitions expert, and he’d been hand-picked for this mission. Pride and patriotic duty called.

He retrieved his dented copper helmet, and a month later, in November 1854, he was sailing for Crimea.

chapter

13

The Russian destruction of the Turkish fleet at the Battle of Sinop sparked the Crimean War.

chapter

13

John had been a boy when Britain mobilized for war against Napoleon’s army, an era during which soldiers clashed in organized columns. But when he arrived in Crimea, John witnessed a new kind of brutality on the battlefield. Improved weaponry and dated infantry tactics turned front lines into massive slaughterhouses—horses barraged by artillery, men dead on their feet. French bands played while miserable soldiers dug as many trenches as graves; wild dogs picked skeletons clean in the snow, while vultures and ravens circled for any remainders.

The attempt to clear the blockade of Sevastopol Harbor was a failure. Russian gun positions prevented the British from getting close enough for John to deploy the explosives, and the siege wore on for another eight months. This was the first war to be photographed and seen in the press back home, where Londoners were outraged. Here was the great British Empire dragged into endless war by little Russia. Britain, as popular opinion had it, should have long since returned triumphant from Crimea. And what an embarrassment to see the beloved and powerful British navy immobilized. The British had to break the siege.

With the harbor impregnable by sea, their only chance was to enter the Sea of Azov and land an Allied army to cut Russian supply routes. Otherwise, Russia could resupply the city forever. But Britain’s grand armada was again useless, as the straits leading to Azov were full of “Infernal machines,” as the

The Crimean War saw the first widespread use of underwater mines.

underwater mines were called—a novelty of the Crimean War designed by Immanuel Nobel, the patriarch of the engineering and industrialist family that amassed a fortune commercializing explosives. (Alfred Nobel was Immanuel’s son.) The mines were designed with metal casings, filled with gunpowder, and detonated with an electrified trigger. It was a new kind of naval warfare, a modern, mechanical, and very effective means of destroying traditional wooden ships. A single mine could put a gaping hole in the hull of a vessel, sinking it within minutes. It would pulp a diver instantaneously.

No British soldier had even attempted to defuse the mines, as they were roped with weights and floated beneath the surface. This became John’s mission, as the British and French sailed toward the heart of the Crimea and Russia’s network of infernal machines. His ship was part of a sizable naval detachment: nine battleships and 47 smaller transports, carrying 16,000 troops.

John was aging and weary and 2,000 miles from his seaside cottage, and he had been given a task upon which rested the fate of thousands of men, if not the success of the war itself. Back in Whitstable, Sarah was distraught at John’s position. “You are not like our poor suffering troops who are compelled,” she wrote to him. “You go from choice…. Now do for once take the advice of a Junior Friend and think you have seen enough.”

But Sarah’s concern would not change John’s mind. He stood on deck, assembling his suit and donning his helmet. Through its three small windows John could now see the horizon, engulfed in flames. A rear guard of British battleships had begun a massive fusillade against Russian forces, but the strait was still dense with mines, and the entire British navy awaited John’s descent in his legendary Deane helmet.

Amid the chaos, John donned the diving suit he’d designed with his brother. He pulled on the same woolen underwear they’d worn, the same red cap, the same helmet they’d fashioned back in Deptford. He checked his hose, signal and safety lines, heaved himself overboard, and disappeared into the charcoal-colored ocean. Air hissed through the hose, bringing with it the odor of the carnage above. But the scene beneath the surface could be more gruesome. At Sevastopol, John saw a nautical landscape of blood and corpses, cavalry horses and soldiers decomposing in the ruins of hundreds of ships. Here, John descended to a seafloor laced with enormous potential for destruction, a dense tangle of infernal machines stretching into the distance. They looked like enormous toy tops, with a four-foot cap tapering to a point, the entire thing filled with explosives. The old sailors and their superstitions had it almost right: The deep could hide monsters, but they were made by man.

The mines were deployed in batches connected by insulated electrical wire, a sort of giant trip wire that extended for miles in the sea. John made his way to one of the mines. Wires stretched off into the distance, running a circuit to dozens of other mines and, somewhere out there, a Russian battery boat that powered the elaborate complex of booby traps. If the electric current was running, any false move could trigger a series of explosions that would kill John instantly and damage the British flotilla above him.

The water numbed John’s hands, making it difficult to handle the wires. He pulled a pair of cutters from his dive belt. It had been 21 years since he and Charles made that successful dive at the Royal George, when he watched Charles disappear down that rope ladder and then waited, looking for bubbles, until his brother gave a reassuring tug on the line. They’d survived then, and hundreds of other times since. But Charles had been gone for years, taken by madness, his life a tragedy. And now, John faced an unprecedented danger alone in a foreign sea. The Deane family had once helped build the Royal Navy, and now John was being asked to defend its power. No time on a lost wreck seeking treasure with his brother had more consequence than this moment, as John positioned the blades of his cutter around the wire that would either disarm the threat or detonate the nearby sea.

John cut the connection—and heard just the sound of his own breathing, the moment passing in relief. The loose ends of the wire drifted to the bottom, and John severed the mine’s anchor rope so it could float like a balloon to the surface, where it would be easily dismantled by sailors above. The infernal machine was no longer a machine at all.

Around him in every direction were more mines, and he moved on to the next one, and another, and another, until the strait was cleared.

chapter

14

John Deane returned to Britain a hero. After he cleared the strait, the Allies took control of the waterways in the Crimea. They landed an army and intercepted Russian supplies, ending the siege of Sevastopol. Shortly after the fortified port city fell, Russia conceded defeat. It lost its naval presence in the Black Sea, and Britain overcame the war’s early humiliations to reemerge as the world’s greatest empire and naval power.

Back home, John was greeted by a celebratory press, which dubbed him the “infernal diver.” The Admiralty awarded him the prestigious Crimea Medal. The Deane family name, nearly forgotten, returned to the headlines. It was a long and strange legacy. Nearly two centuries earlier, John and Charles’ ancestors had designed and built the modern British navy. That navy had helped Britain defeat its European enemies, acquire its colonies, then create a vast empire to fuel the Industrial Revolution. It was in this time of invention that the Deane brothers’ mechanical marvel opened the depths of the sea to discovery and naval dominion. Then, when the might of British maritime power was challenged from below, John returned to assert the Deane presence. In the minds of many, John had played no small part in saving Britannia.

It was less than a month after John’s homecoming that he stood at the altar of St. Alphege Church in Whitstable, waiting for Sarah Ann Browning. The church stone stood gray and the oil lamps gladdened the wooden rafters above the altar. When Sarah appeared, she was accompanied by John’s own daughter, Agnes. During his nearly two-year stint at the front, Sarah had waited for him, distressed by his mission but believing in his abilities. When she learned he’d succeeded at sea and would come home, she’d hoped they’d marry. And John had returned from the depths and asked for her hand. Now she stood in taffeta and lace before her groom, and a fair wind blew in from the sea. John would have another chance at happiness, and he never wore the helmet again.

St. Alphege Church in Whitstable.

The Deane brothers’ seminal contribution to the modern diving era was mostly forgotten; their dive suit was so frequently copied that its origin was obscured for many years. Augustus Siebe, the engineer who assembled the first Deane helmets, largely took credit for the invention and used the stolen design to build a business that thrived for more than a century.

At the 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition in Hyde Park, three years after Charles’ death, John was invited to display the Deane helmet and suit in front of several million visitors from around the world. He credited his brother as an inventor.

John Deane died in 1884 at the age of 84. He was buried in a family row reserved in Ramsgate, a wealthy seaside suburb in Kent.

The site of Charles Deane’s grave is unknown.

The author is deeply indebted to John Bevan, chairman of the Historical Diving Society in Gosport, England, and the author of The Infernal Diver: The Lives of John and Charles Deane, Their Invention of the Diving Helmet and Its First Application to Salvage, Treasure Hunting, Civil Engineering, and Military Uses. Without Bevan’s meticulously researched book and generous assistance, this story would not have been possible.

CREDITS

edited by mark robinson

design by priest+Grace

illustrations by roberto parada

FACT CHECKING by LYDIA BELANGER

ADDITIONAL EDITING by RODES FISHBURNE

Chapter 1

Headline typography by Sunday Büro

Video of water: PinnacleMotino2/Shutterstock

Painting: The Royal George at Deptford Showing the Launch of the Cambridge (1757),

John Cleveley, the Elder. Via Wikimedia Commons

Chapter 2

The Brothers Charles and John Deane circa 1828. by Roberto Parada for Epic

The Great Sea Serpent, according to Hans Egede, 1839. Courtesy the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Chapter 3

Extract from the patent specification drawings of Charles Deane's smoke helmet, 1823.

Public Domain

Chapter 4

Video of diver by Natalie So, Epic. Diver: Harry Spitzer

Deane diving helmet, Photo by SSPL/Getty Images

Deane helmet and dress as illustrated in 1842. Public Domain

Chapter 5

Red knit cap: Balaraman Arun/Shutterstock

Rope video by Natalie So, Epic

Chapter 6

Underwater video by Natalie So, Epic

Chapter 7

The Deane Diving Suit by Roberto Parada for Epic

Chapter 8

Royal Hospital School. National Maritime Museum

Spoils of the Oceans handbill. Public Domain

Chapter 10

Peckham House Lunatic Asylum. Southwark Local Studies Library

Chapter 11

Sarah Ann Browning. Portsmouth City Museums and Record Services

Chapter 12

The Siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War (1854-55).

Detail from a panorama painting by Franz A. Roubaud. via Wikimedia Commons

Chapter 13

The battle of Sinop painting by Ivan Aivazovsky via Wikimedia Commons

Photo of underwater mine. National Maritime Museum

Undersea Horror, by Roberto Parada for Epic

Chapter 14

Crimean Medal. Public Domain

St. Alphege Church. Public Domain

End credits

Water video: PinnacleMotino2/Shutterstock