For the first few million years of human evolution, technologies changed slowly. Some three million years ago, our ancestors were making chipped stone flakes and crude choppers. Two million years ago, hand-axes. A million years ago, primitive humans sometimes used fire, but with difficulty. Then, 500,000 years ago, technological change accelerated, as spearpoints, firemaking, axes, beads and bows appeared.

This technological revolution wasn’t the work of one people. Innovations arose in different groups – modern Homo sapiens, primitive sapiens, possibly even Neanderthals – and then spread. Many key inventions were unique: one-offs. Instead of being invented by different people independently, they were discovered once, then shared. That implies a few clever people created many of history’s big inventions.

And not all of them were modern humans.

The tip of the spear

500,000 years ago in southern Africa, primitive Homo sapiens first bound stone blades to wooden spears, creating the spearpoint. Spearpoints were revolutionary as weaponry, and as the first “composite tools” – combining components.

The spearpoint spread, appearing 300,000 years ago in East Africa and the Mideast, then 250,000 years ago in Europe, wielded by Neanderthals. That pattern suggests the spearpoint was gradually passed on from one people to another, all the way from Africa to Europe.

Catching fire

400,000 years ago hints of fire, including charcoal and burnt bones, became common in Europe, the Mideast and Africa. It happened roughly the same time everywhere – rather than randomly in disconnected places – suggesting invention, then rapid spread. Fire’s utility is obvious, and keeping a fire going is easy. Starting a fire is harder, however, and was probably the main barrier. If so, widespread use of fire likely marked the invention of the fire-drill – a stick spun against another piece of wood to create friction, a tool still used today by hunter-gatherers.

Curiously, the oldest evidence for regular fire use comes from Europe – then inhabited by Neanderthals. Did Neanderthals master fire first? Why not? Their brains were as big as ours; they used them for something, and living through Europe’s ice-age winters, Neanderthals needed fire more than African Homo sapiens.

The axe

270,000 years ago in central Africa, hand-axes began to disappear, replaced by a new technology, the core-axe. Core-axes looked like small, fat hand-axes, but were radically different tools. Microscopic scratches show core-axes were bound to wooden handles – making a true, hafted axe. Axes quickly spread through Africa, then were carried by modern humans into the Arabian peninsula, Australia, and ultimately Europe.

Ornamentation

The oldest beads are 140,000 years old, and come from Morocco. They were made by piercing snail shells, then stringing them on a cord. At the time, archaic Homo sapiens inhabited North Africa, so their makers weren’t modern humans.

Beads then appeared in Europe, 115,000-120,000 years ago, worn by Neanderthals, and were finally adopted by modern humans in southern Africa 70,000 years ago.

Bow and arrow

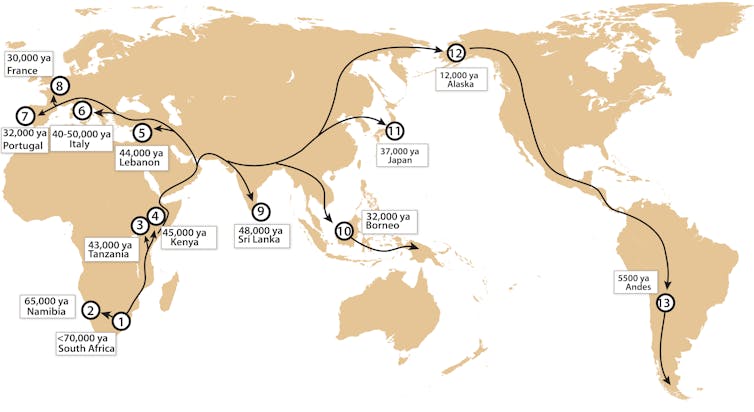

The oldest arrowheads appeared in southern Africa over 70,000 years ago, likely made by the ancestors of the Bushmen, who’ve lived there for 200,000 years. Bows then spread to modern humans in East Africa, to south Asia 48,000 years ago, on to Europe 40,000 years ago, and finally to Alaska and the Americas, 12,000 years ago.

Neanderthals never adopted bows, but the timing of the bow’s spread means it was likely used by Homo sapiens against them.

Trading technology

It’s not impossible that people invented similar technologies in different parts of the world at roughly the same time, and in some cases, this must have happened. But the simplest explanation for the archaeological data we have is that instead of reinventing technologies, many advances were made just once, then spread widely. After all, assuming fewer innovations requires fewer assumptions.

But how did technology spread? It’s unlikely individual prehistoric people travelled long distances through lands held by hostile tribes (although there were obviously major migrations over generations), so African humans probably didn’t meet Neanderthals in Europe, or vice versa. Instead, technology and ideas diffused – transferred from one band and tribe to the next, and the next, in a vast chain linking modern Homo sapiens in southern Africa to archaic humans in North and East Africa, and Neanderthals in Europe.

Conflict could have driven exchange, with people stealing or capturing tools and weapons. Native Americans, for example, got horses by capturing them from the Spanish. But it’s likely that people often just traded technologies, simply because it was safer and easier. Even today, modern hunter-gatherers, who lack money, still trade – Hadzabe hunters exchange honey for iron arrowheads made by neighbouring tribes, for example.

Archaeology shows such trade is ancient. Ostrich eggshell beads from South Africa, up to 30,000 years old, have been found over 300 kilometres from where they were made. 200,000—300,000 years ago, archaic Homo sapiens in East Africa used tools from obsidian sourced from 50-150 kilometres away, further than modern hunter-gatherers typically travel.

Last, we shouldn’t overlook human generosity – some exchanges may simply have been gifts. Human history and prehistory were doubtless full of conflict, but then as now, tribes may have had peaceful interactions – treaties, marriages, friendships – and may simply have gifted technology to their neighbours.

Stone Age geniuses

The pattern seen here – single origin, then spread of innovations – has another remarkable implication. Progress may have been highly dependent on single individuals, rather than being the inevitable outcome of larger cultural forces.

Consider the bow. It’s so useful that its invention seems both obvious and inevitable. But if it really was obvious, we’d see bows invented repeatedly in different parts of the world. But Native Americans didn’t invent the bow - neither did Australian Aborigines, nor people in Europe and Asia.

Instead, it seems one clever Bushman invented the bow, and then everyone else adopted it. That hunter’s invention would change the course of human history for thousands of years to come, determining the fates of peoples and empires.

The prehistoric pattern resembles what we’ve seen in historic times. Some innovations were developed repeatedly – farming, civilisation, calendars, pyramids, mathematics, writing, and beer were invented independently around the world, for example. Certain inventions may be obvious enough to emerge in a predictable fashion in response to people’s needs.

But many key innovations – the wheel, gunpowder, the printing press, stirrups, the compass – seem to have been invented just once, before becoming widespread.

And likewise a handful of individuals – Steve Jobs, Thomas Edison, Nikola Tesla, the Wright Brothers, James Watt, Archimedes – played outsized roles in driving our technological evolution, which implies highly creative individuals had a huge impact.

That suggests the odds of hitting on a major technological innovation are low. Perhaps it wasn’t inevitable that fire, spearpoints, axes, beads or bows would be discovered when they were.

Then, as now, one person could literally change the course of history, with nothing more than an idea.

Comments are open on selected articles and must comply with our community standards.

David Jordan

Haven’t we been here before?

When I studied archaeology in the early 1980s I was taught that, following a long period when migration was the presumed means of culture spread, we had come to understand that culture spread by contact and exchange. Then along came DNA and C14 studies which showed that, in fact, ancient tribes had indeed been charging around the Old World taking their cultures and technology with them rather than it spreading (primarily) by exchange. And that (with a lot of extra subtleties) remains our understanding.

I’m all for iconoclasm but the arguments here seem weak and very hard to test with independent data. 50 to 150km may be typically more than modern hunter-gatherers move about as a group but individuals move much greater distances and it’s not unreasonable to suppose that those who innovate have reasons and abilities to move atypically far.

I’m sorry if this seems ungenerous but it concerns me that we have put so much time and energy into teaching archaeology students untestable stuff which proves to be wrong, because it is fashionable, rather than concentrating on gathering data which then allows us to hypothesise at the edge of an expanding volume of what we genuinely know.

After all, it isn’t as though there isn’t a vast amount of data still to be gathered.

David Jordan

Shouldn’t the title (which I appreciate isn’t in the gift of the author) read “It’s not inconceivable that …” instead of “How …”?

It’s entirely conceivable that the same evidence could support radically different interpretations.

David Jordan

Add “isotope” to “DNA and C14”, of course.

Gustav Clark

I don’t see the article as being about trade vs migration. They are both compatible with technologies spreading from single centres of innovation. In historical times there is no doubt that most people spend most of their lives within 50 miles of where they are born, getting new ideas by trading information, whilst the Marco Polos and the Elon Musks travel the world.

Deena Hai

logged in via Google

I’m not sure if you’re familiar or unfamiliar with admixture or genetics but the world is moving fast. There’s plenty of genetics, in bones, oral history, in each of us alone but primarily there’s a ridiculous amount of adna that backs up thousand year old stories.

So… not sure what you mean about untestable stuff but I do agree that archeology students need to be taught waaaay outside their breadth now. History, mythology, genetics, decolonization. But that’s only because it really should be required. Some places it looks like they started moving forward…

Torbjörn Larsson

logged in via Google

The claimed “adna that backs up thousand year old stories” typically doesn’t exist though. There is a confusion between cherry picked correlation and causation and mostly seen in the soft versions of anthropology.

“You must remember this, a myth is still a myth”, as the song may have said.

I agree with both David Jordan and Gustaf Clark, thanks for the thoughtful contributions!

Terrence Treft

thanks for the interesting article.

but just how can you be definitive “that Instead of being invented by different people independently, they were discovered once, then shared”? what specific evidence, out of millions of years and millions of individuals, is there? even in your next sentence you raise doubt, “That implies a few clever people created many of history’s big inventions.”

and, other timelines place human arrival in the americas much earlier.

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

The arrival of the bow in North America around 12,000 ya (depending on who you ask) doesn’t mark the arrival of humans- that happened much earlier, 34,500 ya or so based on some of the latest work in Alaska (with footprints and tools in New Mexico and Mexico corroborating an early arrival). The fact that people spent 10,000 or 20,000 years in North America hunting- without inventing the bow- is part of the reason to think it’s invention was highly unlikely.

Terrence Treft

point taken. thanks for the clarification. best with your research.

Terrence Treft

and thanks for taking the time to comment. most authors here do not.

Joanna Richardson

Hi Terrencehappy new year

You asked your question on epigenetics on the twin study article an hour or so before comments closed, so the author of that article had no change to reply. The only study mentioned while comments were open was the Dutch Famine Study and the links would be in the comments.

Terrence Treft

hi joanna, happy new year down under.

just looking for an expert’s definition on epigenetics, something i think i have a fundamental understanding about, but a topic not as well defined as genetics for the commoner.

as to this article, given that millions of individuals living fundamentally the same life styles were distributed over maybe millions of years, the term genius might be misplaced. that the invention of otherwise simple technologies to solve the same/similar problems might well have occurred at many sites, as, accident is the mother of invention.

as well, likely some inventions were discovered, lost and re-invented multiple times.

in a modern perspective, we have the technology necessary to control the pandemic, but we choose not to embrace it or improve upon it. of course, i mean the n-95 respirator, many brands now available. vaccines have proven unreliable in preventing infection, while the n-95 is nearly 100% effective in stopping the airborne transmission of respiratory virus.

also, some ‘genius’ invented the ear loop technology to replace the two strap design of the conventional n-95’s, rendering otherwise effective masks into slippery devices that offer little or no protection.

today we are amazed at the invention of fire and spear points, but blind to a stupid, failed ear loop. archaeologists of the future (if there is one) may have a good laugh at our muddling of this pandemic.

stay safe.

Joanna Richardson

I suppose it depends on your definition of genius. I am inclined to think adding shaping and adding a stone tip to a length of wood with twine or glue or both would count, even if someone else had to come up with the wooden spear, possibly with a fire hardened tip, the stone shaping, the glue and the twine. (I would also suggest that twines, cords and threads, possibly even glue, indicate that some of the geniuses were female.)

I am able to cope with washable masks with ear loops, despite wearing glasses which fog up in various shops. It seems that the benefit of masks depends on how many people wear them, how often and in most places.

As in my reply to Paul Burns, I think knowledge transmission was quite likely in the past, as long as land and sea routes permitted travel by the means available at the time. So various kinds of canoes and boats would also have been good inventions. Would the sharing of peaceful inventions, such as cord, be more likely than weaponry?

Terrence Treft

you are entirely correct about the skill needed to fashion things like an otherwise simple tool, such as a spear. simplicity does not negate craftsmanship. the clovis point (banner photo above) is a fine example. it was in its time, roughly about 600 years, the ultimate in hunting technology. some suggest that it and other hunting points exterminated the megafauna of north america. and it is entirely likely that, as trade was well established in north america, that the technology was shared extensively. but some similar points are found elsewhere, too.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z14Fxpg3n4U

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1gr-w6iB_E

making such a point requires the proper stone/materials too, and apparently there was trade of supplies as well. at sites where points were produced in great numbers, many discards are found. but whether this was a skill shared by many or a few select individuals or their gender is not understood.

just how many were produced in total will never be known, but in some areas they still are commonly found. in my own small vegetable garden when i first began turning the soil i found about a dozen (no clovis points), though most were broken (by my intervention or others). now, 40 years later, none.

you should wear a 3m brand n-95 if possible or a reputable n-95 approved by the cdc/niosh. i lost that site. just search it out. no mask/respirator will filter out individual virons. the are much, much to small. but because they are transmitted in respiratory fluids, those larger particles are trapped, most effectively (nearly 100%) by n-95’s.

i sanitize mine by placing them on the dashboard of a closed vehicle or on an oil-filled space heater. this study demonstrates that the virus is made inactive at relatively low heat temperatures:

(sorry, it’s on a different computer. i’ll send it later)

about 150 F for about 5-10 mins is my standard. but i usually err on the side of caution.

https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2012/04/lab-study-supports-use-n95-respirators-flu-protection

there is a link to the actual study in that site.

this organization has advanced n-95’s:

https://www.projectn95.org/

the overall benefits of “masks” (a ubiquitous term) does depend on usage, but my goal is not to flatten the curve but to zero it. wearing a respirator is a self defense tactic.

it is also interesting that the rapid and early expanse of paleolithic migration into the americas cannot be explained by foot travel. more recent theory supports the use of boats to travel down the western coast of north america and into the southern hemisphere. certainly though, that did not occur overnight.

Gustav Clark

Just occurred to me - why do you assume that all hunters were men? It seems to have been true in North America, but that is the place where they failed to invent the bow and arrow. Meanwhile, in historic times many of our fabric based crafts were largely male preserves - making fishing nets, weaving, making shirts. To a large extent our ideas of how people are supposed to conform to their gender are very recent, many being fixed only in the last 50 years.

Joanna Richardson

Reasonable point. It is how they are generally portrayed. Also is does seem to have been the case in Australia, as far as my reading indicates. Australia did not have bows and arrows but did have spear throwers and fish and eel traps. Here basketry seems to have been done by the women and included eel and other water based traps. Also the land/forest/grassland was shaped for hunting by fire as described in Dark Emu https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_Emu and Bill Gammage’s Biggest Estate on Earth https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Gammage#Books

Darian Hiles

Hunters were men because that was their social role. Women were generally working with plants, where probably the most useful inventions were made, including medicines and poisons.

Frank Tuijn

If people reached America before they could have walked over Bering land around the ice they must have traveled by boat South of the ice. And it then would have made sense to continue to use boats.

Terrence Treft

yes, that is a current theory that explains both the trajectory and speed of migration into the americas.

while dates and numbers are not agreed on, a google will provide many sources for more information.

Gustav Clark

There are no videos. No anthropologists journals. Not even oral tales retold a thousand times. If their society was the same as ours then gender roles were ill-defined, save child-rearing, and we are more conformist than 200 years ago. In the days of sail many sailors were women in disguise. Incredible inventions require incredible people.

Proposal: the bow requires familiarity with hearthside and hunting. This was a trans man, brought up with women’s skills and then learning men’s. It takes self-confidence to transition, but you can be a master of everything.

Darian Hiles

Pure imagination. “Not even oral tales”? Some of them still exist in original form today. This is nonsense. You have to be more familiar with the subject than that!

Gustav Clark

This is in itself a breakthrough idea, one that could have been formulated say 50 years ago but which the ‘standard model’ of human history would automatically reject. Historians for the last 100 years have been fighting against the Great Man view of history and instead interpreting all change as part of an inevitable evolution of mankind. I accept most of their reasoning, as each step requires a pre-existing level of technology, but what has always troubled me has been the timescale. Once we have the skill to make a hand axe then why is there such a long time before the core axe. If they arose out of random accidents then only a few hundred years should be needed. Taking your approach I can see that it needed sufficient community resources for one person to come up with an idea, to try it out and experiment before getting it to work. It may have been a few great men working together, but either way it makes sense for one centre to develop it. With the bow there are many steps to master before you get something that is better than a skilled hunter with a spear-thrower. I can not really imagine how a bow could evolve as a weapon, the early versions would have been so obviously inferior to current technology. Perhaps there was indeed an early incarnation of Elon Musk to finance its development

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

It’s a complex problem, and a deep philosophical issue. One model of history might be that societal change emerges as the result of larger social and economic and psychological forces, the masses and not the individual, in a fairly predictable way. This is the model outlined in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series, where the science of “Psychohistory” can accurately predict the fall and rise of civilizations. Another view would hold that single individuals can exert a massive influence and change history, as the villain in that series, the Mule. I suspect they are both the case. Personally I’ve been influenced a lot by catastrophism in paleontology- the idea that a freak event like an asteroid impact can change history- as well as Taleb’s “Black Swan”, where he argues that rare, improbable events exert an outsized influence. It is certainly the case that rare disasters- the Black Death, 9/11, the 2007 financial crisis, the 2020 pandemic- can have a massive influence on history. But isn’t the same thing going to be true of positive events, like innovation?

Gustav Clark

You have hit the bulls eye

Colin Matheson

“But isn’t the same thing going to be true of positive events, like innovation?”

No

successful innovation requires an inventor yes, but also a receptive environment

the bow may have been invented many times, but perhaps didnt catch on because other people were able to do just fine without it, or because it wasnt passed on due to isolation

Gustav Clark

Once a working bow arrives in a society it sticks, it never goes out of use. It is like the gun. Would any serious hunter ever abandon the use of firearms. There is however a problem with the bow, in that it’s initial incarnation would have been very ineffective compared to other tools, and it could have taken a generation to get it up to a state where it could complete. That, and the fact that there is no analogy in nature to suggest it, rather implies that it it could well have arisen just once.

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

I suspect you’re generally correct regarding the “stickiness” of bows, but given the antiquity of bows in Asia its hard for me to imagine the Polynesians were never aware of them. Maybe there just wasn’t a lot to hunt on those islands, and other weapons like clubs and slings were more effective in warfare. The point about analogies is interesting. At least some technologies have natural analogies- did weaver birds inspire human weaving, or swallow nests inspire potters? One issue might be the complexity of the bow- a Creationist might call it “irreducibly complex”, that is unless you have all three components- the bow, the string, the arrow- it’s useless. Unlike, say, an atlatl: where you can start with just a stick, then sharpen it, then add a spearpoint, and finally use the throwing stick. You can create that in an incremental way. I’m convinced there is a connection between bows and stringed musical instruments (which are highly diverse in southern Africa) and have tended to assume the bow inspired the musical bow, harp, lyre, guitar, etc. but it’s concievable it worked the other way around: there is a use for a bow without an arrow, in the form of a musical instrument. Perhaps people playing around with their musical instrument tried to make a game of shooting sticks. Fun to speculate, incredibly hard to test.

Colin Matheson

“I’m convinced there is a connection between bows and stringed musical instruments…Perhaps people playing around with their musical instrument tried to make a game of shooting sticks”

another path could have been from bent saplings with snares attached

David Morley

Or perhaps the difficulty was in getting rather conservative societies to adopt new technologies. Perhaps these innovations (and others) happened many times, but simply failed to take off. And perhaps early versions of them didn’t seem that much of an improvement. How good does a bow have to be, and how skilled must it’s user be, before it offers an advantage?

Gustav Clark

On bows vs spears, an arrow is necessarily very light and so it needs to go deep to kill. A spear can be much heavier; the weight will slow down the prey and it has more momentum to go in. The bow itself must not break too often, nor the string, so it would lack range and force. Once the bow is perfected it allows remote hunting, which is safer and more effective. Intellectually the problem is why would anyone imagine making a bow, there is no analogy in nature, and once imagined how much work would be needed to create a demonstrator. Without a lot of practice that will fail by comparison with a spear plus spear thrower. So some creative pool is throwing all this effort into it, being laughed at, just to implement a dream. The more I look at it the less I can see it emerging more than once

David Morley

Agree.

The alternative is that you adopt a poorer technology and stick with it for the time it takes both to improve the technology and to develop the most effective way of using it. It seems pretty unlikely.

David Morley

Or perhaps you just need the best marketing strategy 😀

Gustav Clark

It needed Elon Musk as head of the tribe plugging away at his dream

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

The key advantage of the bow is its accuracy. Spears and bows are both lethal at long ranges, but the spear is only accurate to around 20 meters, a primitive bow is accurate to about 50 meters. That accuracy also makes it useful for small game like birds that would be hard to hit with a spear. It also gives you more shots (you can carry many arrows) which is useful not just in terms of taking extra shots, but carrying different arrows (blunt for birds, barbs for bigger game, poison for big game). However it has less ability to penetrate deeply, or through thick skin (or an enemy shield) versus a spear. It also requires two hands, while a spear needs only one- so you could hold a shield or a club in the other hand. So it’s not always superior. Some people seem to have held out for a long time before switching.

Gustav Clark

By the time of the battle of Agincourt the bow was a truly lethal weapon. However, I agree that a hunter needs a range of tools. Having raised the question I still cannot imagine the development process. I can see the evolution of a bow for use with a fire-stick - perhaps a child playing with that could have shot an arrow?

A less fanciful question - how does this fit in with Australia and Indonesia?

Owen Parry

Don’t forget that a bow and arrow might have advantages over a spear for small fish.

Colin Matheson

“how does this fit in with Australia”

my guess is that people were doing quite well with the various hunting tools they already had

Gustav Clark

The rest of the world adopted the bow and arrow as soon as they saw it. It just better. The point is that whilst it is massively superior it is absolutely non-intuitive. It looks like it was invented once, in 100 000 years. It never reached Australia, and of course they didn’t reinvent it.

Colin Matheson

one path to the invention of a bow might be from simpler trapping techniques.

for example, you can bend a sapling and attach a snare with a piece of string (which can be made from various things), once triggered the sapling springs back and catches the rabbit

not hard to imagine people messing around with these types of traps and discovering that a released bent sapling can fling a projectile

Darian Hiles

I agree. A further case is the chameleon, which can throw a tethered projectile in the form of an elongated tongue. How does it do it? We underestimate the inquisitive and explorative nature of early people who focused intently on how simple things happen.

Gustav Clark

Most scientific discoveries can be seen as almost inevitable - the problem is recognised, the facts are available to all, it is just a rave to see who puts them together first. The problem is that the winners have a tendency to go to solve more problems, whilst the also rans seem to fall back into obscurity. Wallace may have had an idea about evolution, but Darwin also did major work on coral reefs and barnacles, and his insights carry on inspiring fresh research. Our time scales are shorter now than in the Neolithic, but we still have gaps where the problem is known but we are waiting. Are we waiting for some large black monolith to appear so we can unlock nuclear fusion?

Jon Sturley

Jon Sturley is a Friend of The Conversation

Thanks for the article. This logically makes sense: New technologies are very infrequent, and so unless the transmission of ideas is incredibly slow, it is highly probable that the invention will reach other locations before someone there would come up with the same idea. This does not suggest that others wouldn’t have made equivalent inventions, merely that the velocity of the transmission of existing ideas is much greater than the rate of technological change… no one can invent something of which they’ve already been told!

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

That is an excellent way of putting it! Of course in the modern world, the velocity of spread is so fast, and the barriers to technological spread are so few, it is harder and harder for key innovations to arise more than once. The world being as linked as it is, we don’t really get to play the game of seeing whether other people might invent the same technology or not.

cort johns

logged in via Google

I find that the article makes an interesting case for ‘The Master Mind Inventor’ concept. However, there appears to be an important inventor missing. Although Archimedes was a brilliant mathematician and he did invent the screw pump as far as we know. His mentor, Ctesibius, of the Hellenistic Period, is the elephant in the room, who has been omitted from this list.My research has traced his Hydraulis through 2000 years of artifacts and written records, connecting the Hydraulis with the Industrial Revolution. Starting with Vitruvius describing his observations of the Ctesibius’ Hydraulis, while his boss, Octavian (Caesar Augustus) conquered Alexandria in 30 B.C. The re-discovery of Vitruvius’ ‘De architectura’ at the Abbey of St. Gallen circa 1418 came to the attention of the two ‘Master Mind’ pipe organ builders, qua steam mechanics innovators, Giambattista della Porta and James Watt. Their thorough understanding of the Hydraulis points to a clear connection between the Hydraulis and the roots of our modern steam engines!

cf. “Industrial Revolutions: From Ctesibius to Mars”https://www.amazon.com/Industrial-Revolutions-MacLean-Johns-Ph-D-ebook/dp/B093LQVD3G

Gustav Clark

What you are referring to is a reasonably common occurrence. The Ancient Greeks produced much thought, but they also understood the natural world. Much of what they did seemed to remain at an exploratory level, and this possibly describes Ctesibius’s work. Is there any evidence that he produced working machines? We do know however that the workshops at Rhodes somehow produced the the Antikythera mechanism, a sophisticated device for that was not equalled (except perhaps in Rhodes) for 20 centuries. It is of the same era as Ctesibius, so perhaps there was a whole school of sophisticated engineering that sadly vanished whilst the world celebrated the Greeks for their art and philosophy. The genius of Archimedes was perhaps to realise that the ancient world did have something to offer him.

That said, it remains true that the Roman Empire and its successors through to medieval times seems to have made minimal technological progress. In the Arab world the sciences and mathematics flourished but something in the Roman and Christian world seems to have inhibited invention. Could it be that a hierarchical structure such as the Roman Army or the Christian Church is antithetical to new ideas and innovation?

cort johns

logged in via Google

Dear Colleague,Until now, we know of 2 Hydrauli artefacts, one at the Old Roman Fort Aquincum just south of Budapest and a second at Dion Greece. With the noted Hydraulis author, Melinda Kaba, I personally examined the Aquincum Hydraulis artifacts stored in the vault of the Hungarian National Museum on the Berg in Budapest. I have documented dozens of written and artefactual instances evidencing the Hydraulis through out the two millennia since Ctesibius flourished. While not even Hero of Alexandria claims this invention, there has been a steady stream of chronologies where no other person has been named to claim its priority.Frankly, I tend to think that Ctesibius relied upon his fellow Museon colleague, Euclid, and his “Elements”, Chapter II, to tune and voice the Hydraulis pipes so that when his wife Thäis reportedly played the instrument rendered a melodic sound pleasing to the ear.I have spent many an interested hour reading a wide variety of articles, books, and videos discussing the ingenious Antikythera Mechanism. Jo Marchant’s book gives the general reader a nice discovery mystery, “Decoding the Heavens” where she finds that Archimedes is its most likely inventor. I would like to agree with Dr. Marchant’s opinion yet, as we well know, Archimedes life ended in 212 B.C. in Syracuse at the time of its Roman invasion. Yet from most reports the Antikythera Mechanism was fabricated sometime during the 2nd- or 1st-century BCE.I don’t think it is too much of a leap to speculate that it was likely fabricated in one of the workshops near the Museon, very much like the one that Ctesibius used to construct his first Hydraulis. The fine tolerances need for the bronze or brass manufacture of Ctesibius pneumatic or hydraulic cylindrical pumps had still not been destroyed by Sulla, Julius Caesar, or Octavian during the prime of the Hellenistic Period.Since 1989, I have documented circa 900+ bibliographical sources with about the same number of germane footnotes. In summary, I hold the position that we have a high degree of certainty that Ctesibius along invented the Hydraulis, its hydraulic compressor, its cylindrical pumps, its metal, tuned and voiced organ pipes, and our first instrument keyboard, not to mention the first odometer and Clepsydra or water clock. In my book, had Ctesibius invented nothing more that his versatile pneumatic/hydraulic pumps and hydraulic air compressor which ensured that his pump qua fire extinguisher and pipe organ’s steady air feed is more that enough to include Ctesibius in the front row of the Pantheon of great inventors who changed the world several times over.

Ian Tully

logged in via Google

The Arab and wider Muslim world continued work begun in the Greek and Roman period and enhanced by their contacts with India and China, but although they made advances in some areas such as mathematics, chemistry and cosmology they seem to have been as slow to invent technologies as the other ancient civilisations. One of the puzzles must be why great craftsmen never take their skills beyond the craft level and begin industrialsation. The difference in scale of production between hand-spun cotton and hand-woven cloth and what was possible even with the earliest water powered machinery is immense, and the economic benefits are huge even for those at the bottom of society. Significantly the first standardised mass produced items appear to be gun parts for muskets.

Lesley Burgess

Nobody expects the industrial revolution! (To paraphrase a famous quotation.) The real question is why did it take off in 18th century Britain. The causes — availability and legal framework for private investment capital, coal and canals, and of course an occasional genius etc — provided a nurturing environment that didn’t exist in the ancient world, where slaves and peasants were the ‘engines’. The BBC has a useful summary here:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/topics/zm7qtfr/articles/z6kg3j6

See in particular the case study of entrepreneur Richard Arkwright.

Lesley Burgess

However, the Chinese did invent many technologies well before the 18th century. See this list:

https://www.ancienthistorylists.com/china-history/top-18-ancient-chinese-inventions/

Historians continue to debate why there was no industrial revolution there on the scale of the British one!

Gustav Clark

I would see it purely marxist terms. The country was rich so there was money to invest, there was a breakdown of intellectual conformity, the fruits of the Renaissance had enriched academic life and for a rare brief period it was respectable to be interested in the sciences. It all came together in a similar way that computer applications have today - the money, the ideas, the market, and the social mix. No one understand why Silicon Valley didn’t happen in New England. Also do not forget that the Industrial Revolution by-passed Southern and Eastern England - that’s why there are no cities there now.

Gustav Clark

Probably too hierarchical. Once an invention had pleased the Emperor then it has reached the pinnacle of achievement. What point would there be to mass-produce it?

Ian Tully

logged in via Google

Thanks Lesley, my MA actually covered this period of British history and I’ve been studying it ever since.

In fact there was nothing that Arkwright and the other early pioneers did that was not within the capablities of Ancient Rome. They were not using the very inefficient early steam engines which were mostly used as pumps in the mines, but water power. Canal building is the kind of project Rome was actually quite good at and was largely done by hand not with steam engines. Roman Britain mined for coal and used it to forge iron with technologies already centurries old.

If there was anything holding the British Industrial Revolution back it was a lack craftman skills, it took a while to develop the skills required to make the instruments that helped the scientific revolution and longer still to solve the important problem of precision engineering valves and joints. James Watt was a scientific instrument maker for Glasgow University before his partnership with Boulton. Asia had some of the finest craftsmen ever but their work was directed to the decorative arts.

The first examples of Joint Stock Companies are in 13th century China.and were known in Europe not long afterwards. The Limited Liability Company comes long after the First Industrial Revolution in the late 1840s in Britain and only becomes general in Law ater the Joint Stock Companies Act of 1856. The private enterprise approach could be detrimental as was seen when the British railway system was left to private initiative with the resulting mess a legacy to this day. France under State direction did it more efficienty.

Slaves and peasants were quite abundant in the British Empire. The cheap labour of France was certainly thought of as one reason why they were slower off the mark than Britain in industrialising, but then most British factories and mines employed the cheapest of labour in Workhouse “apprentices”. It is worth noting too that Britain was a highly authoritarian state in day to day reality, only a narrow social class had political representation and enforcable rights. The magistrates in industrial towns were the industrialists who met in boards to set wages, ran the Police Board, and sat in judgement on their employees in the lower Courts. They also controlled the Poor Law Boards should you become destitute when sacked.

As international trading regions China and India had a huge lead on Europe until the “Voyages of Discovery” many of which were, of course, to their regions. They had access to all the things that Europe lacked and had to go out into the greater world to acquire.

The list of inventions is interesting but let’s look at two that were not invented in China, the telescope and the microscope, both using ground glass lenses, something China knew about, and is not technically difficult once you have a clear glass to work with. With no training Herschel ground his own and completely changed our understanding of the universe. These revolutionised cosmology - a specialism in the Asian and the Muslim worlds - and the study of botany and zoology. The resultihg discoveries fed into many other areas including navigation and medicine. China invented paper-making and moveable type but neither led to the explosion of shared knowledge that happened in Europe. Printing in Europe leads to networks of knowledgable people sharing information across borders. The Scientific Revolution that helps launch the Industrial Revolution is a Europe-wide endeavour (the US joins early on too). Given that China was a unified state, with a common written language, for much of the early modern period it should have had a lead.

Lesley Burgess

I agree with all of your observations Ian! It makes the historians’ question of why Britain and not China even more of a conundrum! Are you proposing that the European scientific revolution was a deciding factor? The Chinese certainly had plenty of applied science as well as merchants. Not enough…?

Perhaps the industrial revolution is a case similar to some prehistoric inventions: it was inevitably going to start in one of the likely places, then spread.

Lesley Burgess

PS Ian,You might like to read this article on ancient Chinese optics:

http://www.epsnews.eu/2015/10/optics-in-ancient-china/

Also, the doyen of Chinese history of science, Joseph Needham, addressed the very topic of scientific revolutions with “the Needham Question” of why Europe, not China. See for example his “Science and Society in East and West.”

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

The role of culture and circumstances is another important issue. A lot of prehistory and history may come down to the actions of individual innovators. But certain times and places seem to be far more innovative than others. Ancient Greece was remarkably innovative in many different ways- technology, science, philosophy, politics, theater- and had a remarkable number of innovators in all of these fields. That suggests the unlikely innovation isn’t equally likely to arise everywhere.

The Guns Germs and Steel view would hold that this comes down to things like geography. I think there’s a lot to be said for this. Greece had a lot of sea trade, which brought wealth, ideas, and technologies from across the Mediterranean. I suspect the Mediterranean Ocean is a major reason for the rise of Western Civilization- it keeps civilizations far apart enough that they can evolve in isolation to a degree (at least until Rome conquers most of it) but still exchange technology, philosophy, religion, etc. But then, why Athens and not Sparta, or Alexandria, or Carthage? Or for that matter, why did Greece stop being so innovative, if it’s still in the same place?

Likewise you could invoke economics. A larger society just has more innovators and more chance of someone hitting on an innovation; a more productive economy can employ more people doing things like philosophy and more craftsmen coming up with new ways to make tools, buildings, weapons.

But I think culture must play a major role as well. To the extent that a culture values things like curiosity, creativity, intellectual debate, and is open to novel ideas, it is far more likely to produce major advances, I’d suggest. I think you can make a strong case that Greek culture had a lot of qualities that made it innovative, but it’s hard to quantify the extent to which they valued curiosity more or less than, say, Sparta, and how these values changed over time. I think culture matters- economy and geography aren’t by themselves destiny- but it’s hard to examine in a scientific way.

Frank Tuijn

The “Optics in Ancient China” article mentions the important scientific, technical and philosophical activities during the Warring States Period. Might it be that more and more diverse people had power in these matters, of course especially military and military technologists? The European Warring States period is now lasting more than 1600 years and I do not expect the military to be as useful in this respect as it perhaps was a few hundred years ago.

Lesley Burgess

Good point!

Ian Tully

logged in via Google

An interesting link, and thanks for the Needham reference, perhaps it suggests some solution. What we see in the Western Scientific Revolution, which I think is intrinsically linked to the technological one, are two things abstraction and classification. Gennady Gorelik of Boston University has linked this in with the Biblical idea of Laws governing Creation, (paper on Academia.edu) and much of the work of Galileo, Newton, Boyle et al. is about discovering universal laws not simply collecting examples of what happens if you do this or that. The Chinese optical discoveries do not seem to lead to a general theory about light or perception. Neither Galileo’s nor Newton’s work could be done outside of creating abstract mathematical models and then comparing them with what was observable, the same process as we are still engaged in with Einstein’s work. This is a huge change in thinking and given that actually creating those “other things being equal” situations that it requires for the confirmatory experiments or observations something of a leap of faith.

Along with it comes a mania for collecting data, everything from incredibly detailed star charts to the first full systems of plant and animal classifications. Once you have the data you can start do the comparitive analysis. Trying to understand the dedication of men like Copernicus, Kepler, the Herschels brother and sister as simple enthusiasts is hard for us today. In his student days Charles Darwin joined the beetle collection fad of his day and became one of the top collectors in the UK, he learned to distinguish between dozens of kinds and to see their similarities. His degree did not include botany or zoology it wa an amateur pursuit of his lecturers.

When I read about events such as Volta’s first electric battery leading to Davy’s mad experiments at the Royal Society using electricity in separating gases the sheer pace of the leaps from one discovery to another is exhilarating. I can see nothing like this in earlier eras anywhere, instead we get one isolated discovery after another often centuries apart. From the late 17th century until well into the 19th the gentleman amateur is an important figure linking pure science with practical applications. Readers of Jenny Uglow’s “The Lunar Men” will know of this. The professionalisation of science may actually have set us back.

PS; if you are interested in educational history sites my favourite is Spartacus Educational, where there is a huge trove of documents to supplement the narrative history..https://spartacus-educational.com/

Frank Tuijn

Because of our long Period of Warring States we were able to develop the capability to rob other nations. The Portuguese took over the Indian Ocean trade and Spain the riches of the Americas from about 1500 CE and half a century later Western science and technology started their take off.

Anecdote: Half a century ago I made a new friend who at our fourth meeting said “I’m a racist. I go with my complaint to a neurologist who is an Indonesian and I have the feeling that his ancestors only recently climbed out of the trees.” I said that his ancestors had left Africa with our own a hundred thousand years ago. “But if we are not better men we came there as robbers!” “Yes”, I said, “that’s how I have always seen it”. He went to a gymnasium near Utrecht in the 1930’s and racism was at that time part of the education.

Lesley Burgess

The riches of the colonies plundered by Europeans helped to finance the industrial revolution. I’m not sure about any connection between imperialism and the scientific revolution, except perhaps the stimulation of discoveries in new territories. But no doubt all these developments are linked.

By the way, in your anecdote about the racist, it might be helpful to some readers to explain that “gymnasium” means “high school” in this context!

Frank Tuijn

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gymnasium_(school)

This says that this type of school appeared in the sixteenth century to prepare students for university. In the Netherlands we had “Latin schools” until the state took a hand and introduced the “gymnasium” in the nineteenth century. To most people the main difference with other secondary schools is that it teaches Latin and sometimes still, a little, old Greek. My wife went to a gymnasium and learned very little Greek as well as Latin, English and - her mother’s language, German. She was allowed to drop French early - the language her father taught. I went to a lesser school which taught me French, English and German, all very badly. I needed those languages at university so had to put in that effort later.

Frank Tuijn

I think that the scientific revolution was supported by crumbs from those stolen riches.

Ian Tully

logged in via Google

One would have to ask given these conditions why the rather more advanced civilisation of Egypt did not progress beyond the “craft” use of knowledge to scientific abstraction. Even allowing that “Greek” can be as misleading a designation as “Roman” when talking about the Classical World it is people who identifiy themselves as in the Hellenistic tradition who we remember as the mathematicians and proto-scientists. The Egyptians had long used the square on the hypotenuse formula with right-angled triangles to redraw fields but they did not come up with Pythagaros general rule for example.

It is probably true that, as the Africanists continually tell us, that much of Greek knowledge has Egyptian roots but it is not just because our tranmission is via Greece and Rome that we do not credit Egypt with it. It is in Alexandria and not Thebes or any other ancient Egyptian city that intellectual debate flourishes.

The Egyptian economy was central to Mediterranean trade, under the Roman Empire it was Italy’s breadbasket. The large number of new settlements from this period show that migrants were attracted there. Its population was always considerably greater than that of Greece or even the Greek diaspora. Rome, with a population of 1 million at its Roman Empire peak was never a great centre of innovation despite being something of a meltig pot. We might remember that at the start of the 19th century Britain’s population of 10 million was much smaller than that of France. at 29 million which had historically had at least a quarter of Europe’s population until the Revolutionary Wars created a demographic crisis. Admittedly London was already the largest city in Europe.

It is certainly true if you look at the early Industrial Revolution in Britain that there is a remarkable multiplier effect. Each innovation creates new needs which require further innovation, and the centres cluster because often the factories and mills have their own workshops on site. You can easily see in the history of Clydebank how mill-owners requiring steam engines branch out into engineering companies and ship-builders, all financed by their own banks in an often family network of entrepreneurs. The same families often lead in other areas too, James Clerk Maxwell unites two highly influential ones.

Geoffrey Watson

The main part of this article about the ancient spread of various technologies is fascinating. However the hypothesis that this pattern required “stone age geniuses” doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

In my opinion, if anything the examples put forward as modern analogies support the opposite view, that most inventions are inevitable. The prominence of Jobs, the Wrights, Watt etc are all examples of being the cleverest, luckiest or most dedicated out of a number of people all seeking a technological solution to a well known issue at the same time. I think that if none of these geniuses had existed the world a few centuries on from now would not be noticeably different.

Technology is driven by need, and humans have always strived for an optimum technology. For instance the bow and arrow has advantages and disadvantages, and in many cases if you already have the spear, the woomera, the blowpipe, or the slingshot, the advantage of a bow may be marginal or non-existent. So the need to invent it might not exist.

Gustav Clark

In retrospect just about all inventions appear to be inevitable. The challenge is to master time travel. However in modern times it is not the inventor who matters, rather it is the entrepreneur who sees the potential of an idea and pushes it’s development. The world is awash with ideas for handling climate change, but only photovoltaics, wind and batteries are being implemented at scale. If we mastered fusion tomorrow all that would happen would be 5 years of wrangling about who is going to pay for another demonstrator. To save the world we shall need an individual who sees that this will make him immeasurably rich, puts his money where his heart is and rolls it out across the world. After which you will see just how inevitable it all was.

Sian Parkinson

Very interesting article. It seems to me that the second essential element to a lone genius theory is the ability to communicate with others so the discovery can be disseminated. What we are talking here is the mass communication from tribe to tribe over thousands of miles. Maybe one person invented something but others spotted the potential and acted on it?

It’s always been humans’ strength not so much inventing things in the first place but sharing (or copying) that knowledge

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

Yes, you’re right- if you invent something, and nobody knows about it, does it matter? Columbus and the Norse both ‘discovered’ the New World, but Columbus’ voyage was widely known and would lead to additional voyages, the Vikings’ adventures were not- to the extent that almost 1000 years later, people debated whether they’d even been there or not.

Geoffrey Watson

We are talking about useful inventions here, so anyone who who saw the “new gadget” in action would want one. Every human group has contact with its neighbours, most often friendly, sometimes not. This contact is so useful that it is generally organised into trade links that are fostered specifically to facilitate the exchange of desirable objects. So over thousands or tens of thousands of years the long distance transmission of “inventions” is to be expected.

John Ocafrain

logged in via Google

You seem to have conveniently forgotten pottery and metallurgy as “repeatedly invented”. Let alone the stone building methods! 1 million years of stone age and within 10 000 years all that is invented separately and independently? I don’t believe that that paradigm has a leg to stand on.

Deena Hai

logged in via Google

How do I put this nicely? Mate, you have no clue what you’re talking about. This is unresearched, backdated colonial gaze hogwash. No mention of Denisovans and their many discoveries. I recommend you give David Reich a read, visit his Harvard lab. Read or listen to Razib Khan, who makes history and genetics pretty straightforward. Add to your repertoire, Rumi and journeys on the Silk Road. Read about Ancient North Eurasians. Pretty much everything as we know it was invented in Central Asia or North Africa, the former includes the Indus Valley. Here is some more reading. Gedrosia. Ottoman Empire. Scythians, Saka. The Bajau peoples. Mamluk dynasties. Safavid. Dehli. Good god I can’t

A small brown skinned female child was making intricately crafted jewelry 300k years ago, they lived in advanced cave systems and followed solar calendars somehow still. And dude, the Fertile Crescent to Rome all had plumbing systems that Europeans couldn’t figure out for hundreds of years. Phoenicians brought with them language and symbols they learned a long the way and taught and shared. Technically doesn’t begin, nor does innovation, with just a handful of, albeit very studied individuals. Aka white dudes. And nary a mention of Newton either.

Gustav Clark

Well, my immediate reaction is that you know something, but you need to back it up with some proper work. Get yourself a PhD.

In displaying your erudition you have omitted all of the kingdoms of Africa, of which there were many, make a start with Great Zimbabwe. You also seem to have forgotten China. I can say definitively that we know nothing of the discoveries made by the Denisovans. That does not mean that they didn’t make them, just that statements need evidence. I guess the real problem for your tirade is that the article was almost entirely about events long before the societies you claim to know. The time scales of evolution are vast and ungraspable, human history is a bit easier. The Neolithic age lasted c 1500 years, something like from the withdrawal of the Roman legions to the death of Victoria. That’s a long time with very little innovation going on.

You are right that there is lot of new work going on - to keep up you need to keep a critical eye on archaeology, population genetics, linguistics. You also need to keep your mind open to new ideas. It is very easy to get trapped in the feeling of the inevitability of evolution, but every biologist knows that is a total fallacy. We could have got to where we are today and yet still not invented the bow and arrow.

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

The length constraints do not really allow for treating these issues in depth or with nuance. The original version went into more depth here- making the explicit point that what has been called “Western Civilization” really draws broadly on innovations from around the world- Greek philosophy and science, Roman engineering and politics, Jewish ethics, Egyptian letters, Indian mathematics, Arabic numbers, lots of Chinese technology (gunpowder, compasses, paper); this was cut out during the editing due to length constraints. The prehistoric record suggests something even more remarkable- at least some of our innovations may come from other species, like Neanderthals.

And I would love to name a wider range of innovators but unfortunately, the people who invented the stirrup, or gunpowder, or the compass- we don’t know their names.

With respect to the Denisovans, I did consider this, but we still know very little of them, or their technology, so I couldn’t find a clear case where an innovation could be attributed to them. We have a finger bone, a few teeth, some skulls that (likely) belong to them, not a lot of record of their technology as far as I know. It would not surprise me if Denisovans came up with innovations but if they did, I couldn’t find anything in the literature about it.

Gustav Clark

This is raising more questions for me. I have always understood that the spear thrower was ubiquitous, but it seems that it is unknown in Africa. It turns up in Europe, America and Australia, but perhaps there has been a 2 or maybe 3 independent inventions

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

The spear-thrower is pretty widespread, being used in prehistoric Europe, by Clovis people and historically by Aztecs and Eskimo in North America, Australians; there’s no good evidence it was ever used in Africa as far as I know. One possibility is that the spearthrower was invented by the Out-of-Africa people before they left Africa, or soon after, and carried with them. Alternatively, it could have been invented several times. Unfortunately it’s hard to tell. The size and shape of a spearthrower point can overlap with that of a thrown spear to where it’s difficult to conclude whether it was hand-launched or with a thrower. The key thing to test these patterns is whether these technologies show a continuous/successive distribution as expected for single invention (showing up one place, then farther and farther away at younger at successively younger dates) or a disjointed distribution (showing up many places, with nothing in between) as expected for multiple. It doesn’t seem we have the evidence to draw these inferences for spearthrowers yet.

Colin Matheson

Steve Jobs? I dont think so, he just bullied skilled engineers to package things that had already been invented into a marketers dream

John Church

Nicholas R Longrich, with respect, what a typical male view of history.The most important innovation was when the first female fashioned a sling to carry her baby. Until then we were browsers, eating where we found food.Being naked and needing our hands to carry a staff for protection or carry a child we had no way to carry anything else.She changed all that and also started women’s fascination with changing their appearance.She transformed our species into gatherers.Now we could split up into different foraging parties and meet at a central location to share.For 30 yrs I listened to African women tell their folklore and it is nothing like the the history we teach kids.

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

The ability to use a sling to carry children would have been one of the most important inventions in history. Unfortunately that innovation- like many others- can’t be tracked as done here for bows, since it wouldn’t have preserved. The vast majority of ‘stone-age’ hunter-gatherer technology wasn’t actually stone- it was skin, wood, sinew, and soforth, as in modern hunter-gatherers, and so it wouldn’t have preserved. Some of these innovations were almost certainly made by women- houses, for example, are constructed by women in Bushmen and Hadzabe tribes, so it’s likely women were responsible for many innovations in making early houses. The tools that do preserve well are often weapons- spearpoints, bows- which are traditionally made and used by men. So the archaeological record probably gives us a better picture of the tools used by men than women. It is quite likely that beads were invented by women, however, since Bushmen women are the ones who make beads today.

Paul Burns

Thanks for the article.

Newton wrote about standing on the shoulders of giants, that he achieved what he did thanks to earlier advances. The same is true of early techologies. Take the bow and arrow. Earlier innovators had developed the working of wood, the use of stone tips or the hardening of a pointed end with fire, and the making of string from sinews or fibres.

I admire modern innovators, But let’s not lose sight of the fact that all of them at least learned to read, write and do some arithmetic from school or family. Some had university education. Jobs shared ideas with the Homebrew Computer Club. The more complex a new invention or theory, the more likely it needs many inputs from the wider culture.

Perhaps the greatest innovators are those who use their genius to overcome conventional thinking that blocks progress.

Geoffrey Watson

The whole “great inventors” idea idea doesn’t stack up. There were many other contemporaries doing what Jobs, Edison, Tesla and the Wrights were doing at the same time. Watt possibly made the most personal impact.

Paul Burns

I think you overstate. The creativity of some individuals create a profound new understanding - e.g. Einstein’s four ground-breaking papers in 1905. Others are outstanding in the range of their inventions - e.g. Edison and Tesla.

With the Wrights, they may have had the first powered flight, but several contemporaries were working on the same idea because many had come to suspect that engines would make flight possible. And how far would any of the early aviators have got without the internal combustion engine and refinements made to it that increased the power delivered while reducing the weight?

In other instances, more than one person arriving at the same breakthrough does not detract because of the scale of the breakthrough. e.g. Darwin and Russell identifying the role of evolution and promoting the concept (in Darwin’s case after much hestiation) despite the hostility of those who insisted on a literal Bible.

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

With the Wright Brothers, the key innovation probably wasn’t coupling a motor to a glider; it would have been obvious that the high power/weight ratio of small gas engines should make powered flight possible (and many were attempting this). The Wrights’ key contribution was developing 3-axis control, specifically by adding roll control to their aircraft. The system they used- wing warping, which let the aircraft roll into a banked turn- was inspired by birds and was later replaced by ailerons, but it was critical to making flight controllable, and nobody else was doing anything similar. They also did early work with wind tunnels. The argument isn’t so much that we wouldn’t have aircraft without them, as that we might have had to wait a few more years before it happened; they accelerated the inevitable. Of course it’s all sort of speculative, we can’t rerun history, or see what a parallel universe without the Wrights looks like. But with the widely separated stone age people, we have effectively separate experiments, almost like parallel universes. Does technological progress in the New World, Old World, Australia, etc. follow similar paths? In some ways it does, in some ways it doesn’t. The New World didn’t invent wheels or bows, for example, or domesticate animals to ride. They do show a lot of parallels however- pyramids, large hierarchical civilizations, elaborate state religions, calendars, mathematics.

Gustav Clark

I don’t think that the modern world is much of a guide to stone age times. Steve Jobs didn’t invent anything significant, and I been really do not know who did invent the mobile phone. Work like that is done by companies or groups working together/in competition. We still have genius mathematicians and scientists. EO Wilson, Feynman, these guys thought for themselves, I do not believe that there could have been another Godel, or Cantor, and without them about half of modern mathematics is missing. In technology I think you need to go back to medieval times to find decent analogies to inventing the wheel. After the giants are too well known.

Joanna Richardson

I had been hoping someone would mention string, twine or thread.

While archeology depends on things that do not rot, the invention of cords is easily drawn from finding bows and beads, both mentioned in the article but the form of which which must have come after the making of string or thread. I might posit that cords cut from tanned hides would have followed curing hides and sting could be twined from human hair. These humble and rather gendered items may fall outside the notions of genius but twine is very useful and leads to many things other than bows, including woven cloth and basketry. The other peaceful inventions which accompany string are decoration and dying or painting. However these can also be used a power symbols and display threats when bows and arrows are novel or harder to see in displays of aggression.

With such nonviolent articles I do quite like the gift and exchange method of transferring ideas across populations.

I would posit that some (even many) of the prehistorical geniuses were female. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/the-overlooked-innovation-woven-throughout-human-history/2020/01/09/11b9c0fe-f4f4-11e9-ad8b-85e2aa00b5ce_story.html

Paul Burns

Thanks for your comment and the link.

A pay wall stops me seeing the title and author of the book being reviewed. I would appreciate knowing these as the little I could read added to my interest.

Joanna Richardson

Sorry, I assumed that if I could see the review that others would be able to, my mistake. The book is;

by Kassia St Clair

In terms of this article and inventions of the past, there are separate chapters on topics such as the linen bandages of mummies, the amount of labour to make the sails of viking ships and why wool was good for sails, sports clothing and fabric from spider webs.

I found it well written. Each chapter could stand alone but fits into the overall story through time.

She has also written https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Secret_Lives_of_Colour but I have not read that one, although the topic also interests me.

Nicholas R. Longrich

Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, University of Bath

In writing (and discussing) this article it did occur to me that many key early technologies were probably invented by women. To the extent that women in many traditional societies tended to be less involved in hunting and more involved in making clothes, in weaving, textiles, and soforth, it’s highly likely that women invented key innovations like cords and string, beads, sewing and sewing needles, shoes, coats, baskets, ceramics. Again, we know less about their origin and spread because most of these things don’t preserve as well as stone tools. I would guess a man invented the bow, but that the string may have been invented by a woman. It’s also possible that string spread with beads into southern Africa, spurring the development of the bow. Bows appear in Africa about the same time as beads do- which require a string. Coincidence? Maybe, maybe not.

Paul Burns

Thanks Joanna. I have ordered and very much look forward to the book.

Gustav Clark

Weaving is an interesting case. The belt-strap loom leaves no trace but the vertical loom needed loom weights, making them recognisable in the fossil record.

Joanna Richardson

I had also been thinking of plaiting of hair or string, as a precursor of various forms of weaving.

I assume a belt strap loom is similar to the back strap looms I saw in Bhutan.

Joanna Richardson

Finding pieces of woven cloth or looms may not be the only evidence to establish when the process of weaving began. For example;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silk

I would guess that silk thread would not leave enough of a trace compared with pieces of fabric?

And linen goes back even further;

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linen

Joanna Richardson

Thanks for the article and for responding to comments, including mine.

Gustav Clark

I know of belt/back strap looms from South America - they seem to be ubiquitous. It would be hard to create something big, maybe 1m x 30cm, but multiple strips can be joined end to end and side to side. They have the great virtue over normal looms in that they are very easy to transport, and with a string heddle they are require so little skill that I can make one.

Gustav Clark

Joanna, the paper with the flax fibres is very interesting (and accessible). Inter alia they had a mixture of plant and animal hairs, and a perforated bone needle. It’s Upper Palaeolithic with core flint working. We must be getting such small snapshots of how people lived at that time - caves may be useful but there must have been thousands more settlements in open country where nothing survives.

Ian Tully

logged in via Google

The mention of the Wright Brothers’ wind tunnels raises the issue of how fortuitious circumstances help with innovation. They just happened to own a barn through which the wind blew fairly stongly and consistently which allowed well over 100 tests of airframes. If the barn had been set at a different angle would they have succeed in beating the competition?

It certainly appears that those cut off from cultural transmission simply do not progress. The aboriginal inhabitants of Australia, Papua New Guinea and even those remarkably far flung relations of theirs in the far south of the American continent do not move out of the paleolithic period. The Tierra del Fuegans were a particularly shocking example to early European explorers, and seemed almost more like seals than fellow humans. Yet not so far away from Australia or New Guinea in Java, Sumatra and the Philippines we have a succession of highly evolved cultures open to innovation along very long transmission routes.

Sergio Bouza

logged in via Google

I don’t see the logical reasoning in going from someone doing something extraordinary to someone being extraordinary. I don’t think one clever person makes improbable innovations, I think clever enough person, as all of us are, in the right conditions and with the right preparation make the innovations. And some might be hard to come by than others, but nothing extraordinary there. Is not just that previous knowledge need to exist, is that the society itself have to be on some form for innovations to happen. You do speak about the first millions of years without nothing happening, where were the geniuses then? Why in the modern times all the geniuses happen to be from the rich occidental world?

I think that the extracted implication of stone age geniuses is not really necessary. As you say, there is always a level of technology spread, so instead of thinking that at some point progress may have been highly dependent on single individuals it can be said that at some point human society as whole reached a point where innovation dissemination reached a level where it started to overcome more and more the odds of individuals innovations. It seem to me more logical to think that at some level of technological spread is easy for the invention of the bow to spread instead of happening two times that to think that at some point human technological evolution happens to depend of something that apparently weren’t nowhere before as geniuses.

But anyway I think that this is another innovation in itself, or a sub-product of one, someone thought that doing something extraordinary, makes you extraordinary and then you deserve more respect or whatever, probably being a king or being a chosen by god, and we are still dealing with that. I remember from an archaeological talk that it seem that during the first 7 thousand years of settlements all the houses seem to be of the same size and then someone come with the idea that they deserve a better house than the rest. Is not natural or normal, is another idea and it probably worked fine, most of what drove innovation in the modern or classic times was people rich enough to have free time for it, but I think that now that idea is no longer useful.

As we need bigger and more complex installations to make innovations is clear that a biggest implication by the society is necessary and every one have to enjoy the credit for that. As we are celebrating the launch of the Webb telescope and hopping it goes well, a lot of papers would come from it, but they would come thanks to the taxes paid by everyone and if we want to have more taxes to build even better things, I think is about time we start to tell people a lot more that they are participating in all of this. They always have, but without working societies and public investment we are going nowhere and if we don’t start to share recognition it might not happen. And I think is more close to the truth, I don’t think anyone working on the CERN is better than anyone else, it just happens they are lucky enough, or have the interest, to have ended there.

I think that then, as now, one idea could literally change the course of history, and whoever have it deserve some recognition, like we all do for everything we do, but without blowing it out of proportion.

Gustav Clark

Good reasoning. Now apply it to America, with no wheels or bows or animals to ride, or Australia, in a similar state. Or Neanderthals who never madtered the bow. Does your theory predict these missing inventions.

Al my life I have been taught to think like you, that it is all down to society and economics. It was politically convenient but quite wrong

Sergio Bouza

logged in via Google

I don’t understand your point, can you please clarify?

Gustav Clark