Theodore Nash

June 1, 1952, was Whitsunday, and provided the young Michael Ventris with a convenient break from his duties as an architect. At the end of the day he would write his 20th Work Note on Minoan Language Research, with the somewhat disbelieving title, “Are the Knossos and Pylos Tablets Written in Greek?” Responsibility was disclaimed: this was only “a frivolous digression”, that would “sooner or later come to an impasse, or dissipate itself in absurdities.” It became instead one of the great intellectual achievements of the 20th century.

Discovery and Background

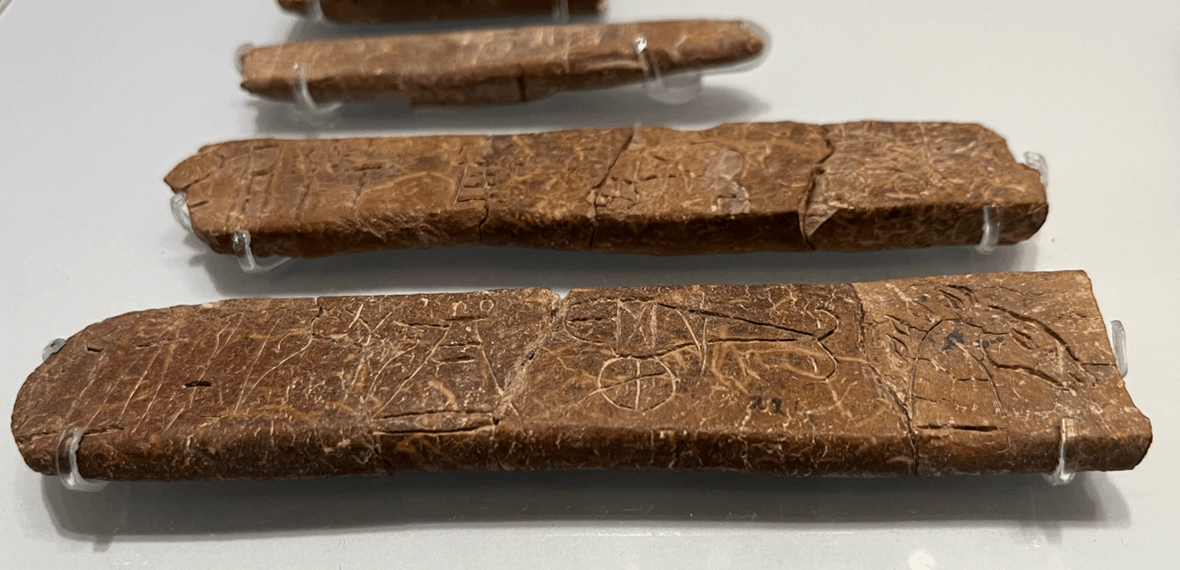

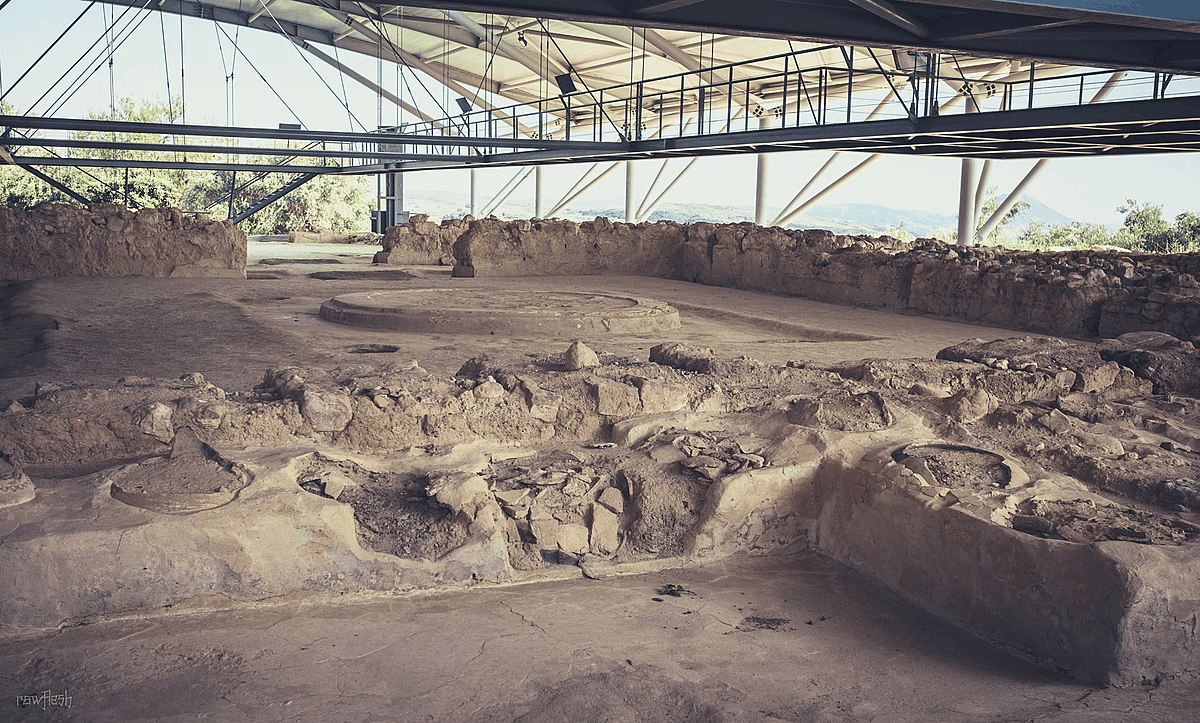

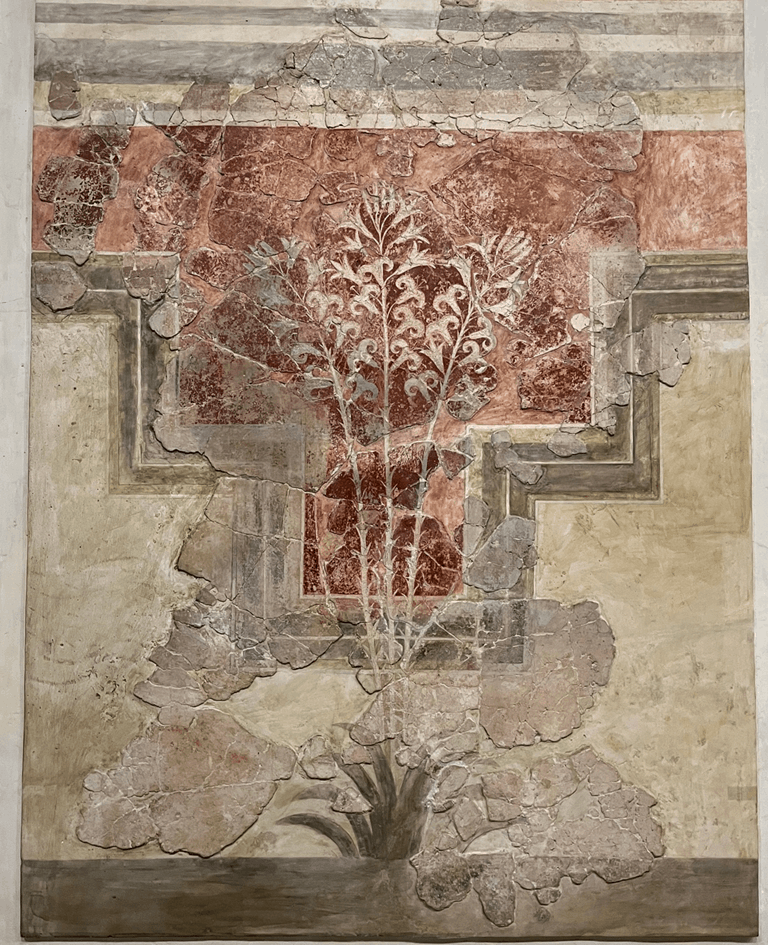

The first Linear B tablets had been discovered at Knossos on the island of Crete. Kephala Hill, as it was then known, was one of the few true ‘tells’ in the Greek world and preserved rich layers of inhabitation dating back to the younger stone age (7,000 BC). The archaeological significance of the site had been clear already in the late 19th century, its first excavator being the fatefully named Minos Kalokairinos. He found great storage jars, pithoi, from which the locals began to call the site Ta Pitaria. These had been placed in hallways of great stone blocks, many carved with curious but distinctive signs.

At a time when Heinrich Schliemann’s excavations were still new, and no unified sense of a Greek Bronze Age had yet been articulated, the reaction to these finds was muted. But in the early 1890s, Arthur Evans, the director of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, became interested in the pictographic signs found carved into semi-precious stone seals that had started to appear in Greece. These were all said to come from Crete. So, in 1894, he visited the island, and was shown the site of Ta Pitaria; he became convinced that the signs carved on the walls might belong to an ancient and forgotten writing system related to that which he had found on the sealstones. A year later, on returning to Crete, he was also shown “a burnt clay slip… said to have been found on the site of Kephala, presenting some incised linear signs which seemed to belong to an advanced system of writing.” This, too, was either found or disturbed by Kalokairinos’ digging, and was the first Linear B tablet known to modern investigators.

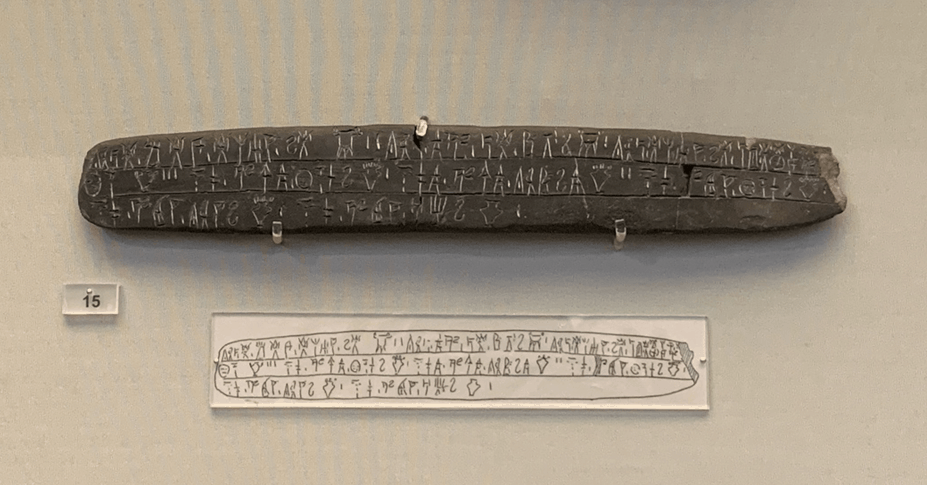

In 1900, having purchased the site, Evans was able to begin his own excavations. On March 31, he found “a kind of baked clay bar, rather like a stone chisel in shape though broken at one end, with a script on it and what appear to be numerals… It at once recalled a clay tablet of unknown age that I had copied at [Heraklion] also found at Knossos.” In the following years of excavation he would find over 4,000 more, albeit many of them in fragmentary condition. He would also find evidence for two other writing systems: the pictographic Cretan Hieroglyphic that he had first identified on sealstones; and another, less polished linear script. The tablets bearing this script were often disorganised, lacking ruled lines and word dividers. Evans classified it as the Linear Script of Class A, against the more regular Linear Script of Class B: our Linear A and Linear B.[1]

It is one thing to excavate material, but quite another to publish it. Though Evans did produce the monumental Palace of Minos (6 vols, 1921–35), this was more a synthesis of Minoan culture as he had come to understand it than a proper archaeological publication. When Evans died in 1941 (believing, if we can credit Maurice Bowra’s report, that Knossos had just been bombed by the Germans), the vast bulk of the tablets remained unpublished. So responsibility for this material passed to Sir John Myres, the recently retired Wykeham Professor of Ancient History at Oxford. Myres had worked with Evans on Crete as far back as the 1890s, but in his retirement lacked the vigour required for this difficult task.

That Evans had published so few of the tablets in his lifetime undoubtedly delayed the possibility of decipherment. When investigating an unknown script, the greater the quantity of evidence available, the greater the possibility that recurring patterns may become visible, and from these the underlying structures deduced. Alice Kober, a professor at Brooklyn College, embraced this challenge in spite of the limited material, managing to make observations that guided the way to a successful decipherment.

From 1943 to 1950, Kober published a series of articles in which she demonstrated that Linear B was used to spell an inflected language – that is, a language (like Latin and Greek) which changes the endings of words to express their grammatical function. Kober would eventually collaborate with Myres to get the Knossos tablets published, but died in 1950, aged only 43, too early to see flowers blossom in the garden that she had so painstakingly tended.

More significant even than the publication of the Knossos tablets was the beginning of excavation atop the Englianos ridge in Western Messenia in 1939. Here Carl Blegen, returning to Greece after his great excavations at Troy, would uncover the Palace of Nestor at the Homeric “sandy Pylos”. On the first day of excavation he uncovered the palace’s archive room, and in that year alone found some 600 tablets. He entrusted study and publication of these to one of his graduate students, Emmett Bennett, who, after the interruption of war, was able to complete from photographs a study of the Linear B signs in the Pylos tablets. This in 1947: in 1951 he added a full transcription of the same tablets, which would provide a major stimulus to Ventris.

Especially in recent years, which have seen a new celebration of Kober’s work, it is probably Bennett’s achievement which is the most overlooked in popular accounts. But it was he who established which variations were possible within individual signs (as I vs I) and which truly separated two signs (as G vs C). Without this, of course, no attempt at decipherment could stand on steady feet.

It was against this background that a young English architect took an interest in the problem. When Michael Ventris was still a pupil at Stowe School he saw a display of Greek and Minoan art at Burlington House; and by the sort of accident that changes the path of one’s life, was given an impromptu tour by Sir Arthur Evans, who happened also to be visiting. After viewing some tablets, Ventris had to confirm something that he had heard: “Did you say the tablets haven’t been deciphered, Sir?”

The challenge was seductive. Over the next few years, he entered sporadic correspondence with Evans about the tablets, sometimes offering suggestions, sometimes apologising after changing his mind (“Actually I was only 15 at the time,” he wrote at 17, “and I am afraid that my theories were nonsense.”). But by 18 he had settled on the theory to which he would cling until proven wrong by a frivolous digression. This was that the language of the tablets should be Etruscan.

As M.G.F. Ventris of London he submitted a manuscript entitled “Introducing the Minoan Language” to the American Journal of Archaeology, which was accepted and published in December 1940. An offprint sent to his former Classics master at Stowe bore a rather sheepish note: “I thought you had better see this… I did not tell them my age.” Today, as with most pre-decipherment scholarship, it is read chiefly as an historical curiosity (“the fantasy with most followers appears to be that which makes Minoan [Linear B] out as Greek”), though his insistence that Linear B and the related Cypriot syllabary should share sign values would eventually prove significant.

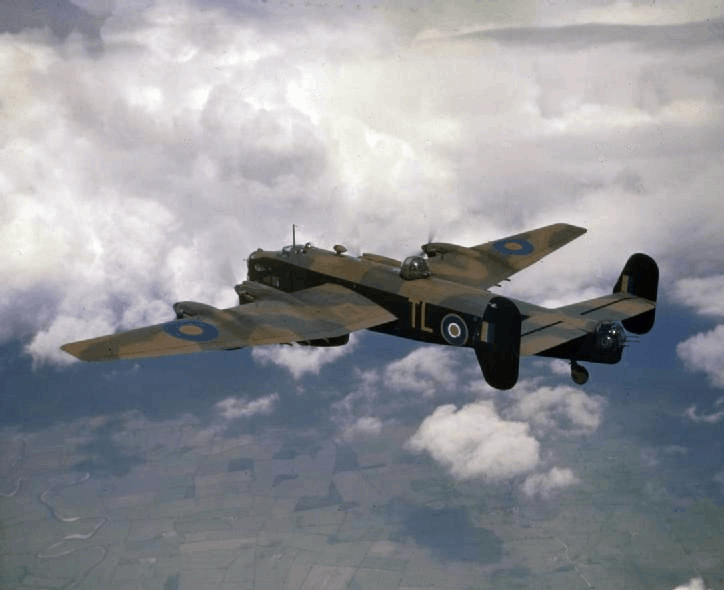

During the War, Ventris served as a bomber navigator in the RAF, and the story is told (though it has rather an apocryphal air) that, once he had set a course for his pilot, he would clear some space in the plane to pore over Linear B texts. After the War his architectural studies took priority, and though invited he did not assist Myres and Kober with the Knossos tablets. In late 1949, he circulated a questionnaire to everyone he knew to be working on the problem, now remembered as the “Mid-Century Report”, but it was not until 1951 that Ventris returned seriously to work on Linear B.

The first of his work notes is dated 28 January 1951, and begins: “With the forthcoming publication of the Linear B inscriptions from Pylos, it’s likely that there will be an intensification of Minoan research work and the hope of some definite progress.” Writing at a pace of just over one note per month, he himself would have the answer in less than a year and a half.

Principles of Decipherment

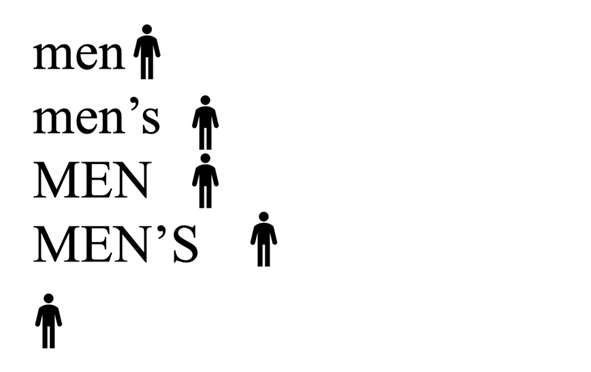

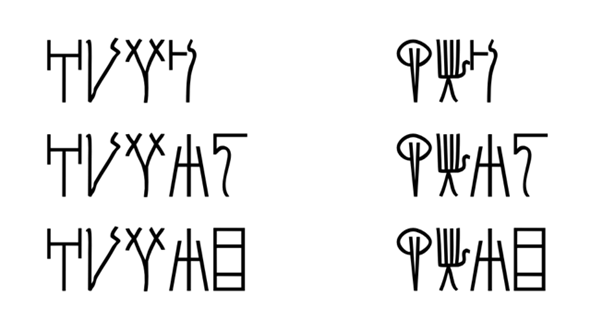

Mycenaean tablets are quite austere records, and even before decipherment their basic structure could be easily grasped. Words, conveniently divided, generally appear in groups of one or two. These are often accompanied by signs of obviously pictographic nature, such as a horse’s head or chariot. Often a numeral follows. The concerns are with who has how many horses, or where they’ve taken them, but rarely with just why they have them, or what they might be doing with them. There are few complete sentences, and very little syntax: information is conveyed with a minimum of fuss. In this respect they greatly resemble modern bathroom signs. Take the following:

men

men’s

MEN

MEN’S

M

The English-speaker in search of a toilet knows that these all mean the same thing. He knows that the minuscule m is the same as M, e the same as E, and n the same as N, so these are not different words; he knows that, while strictly the possessive is correct, “men” is quite the same as “men’s”; and he knows that, when faced with a single door at the back of a restaurant, M will certainly stand for men(’s), especially if next to another door with a W on it. But he knows this because he was taught his abc’s (and ABC’s), and has been using public toilets for most of his life. 5,000 years, to the alien archaeologists and cryptographers trying to make sense of our terrestrial ruins, this will not be quite so obvious.

But Linear B and toilet signs offer another aid: the use of ideograms. These single signs represent not a word in any language, but rather an idea, often by form of pictorial representation. We may find on our sign:

Because in each case the word is accompanied by the same ideogram, our alien friends may develop a certain confidence that “men” is quite the same as “MEN”, and a suspicion that grammatical markers such as the possessive don’t mean all that much. Assuming that they find enough toilet signs, the aliens will be able to establish a relationship between the word “men” and the stick figure, even if they do not yet know the equivalent in their own language. They will also know that M/m, E/e, and N/n are the same letters in other contexts, and that a final -’s can be a grammatical marker. And, though no doubt quite different from their tentacled bodies, once they have dug up a grave or two, or seen any art that has survived the conflagrating years, they might even realise that this symbol represents a human body.

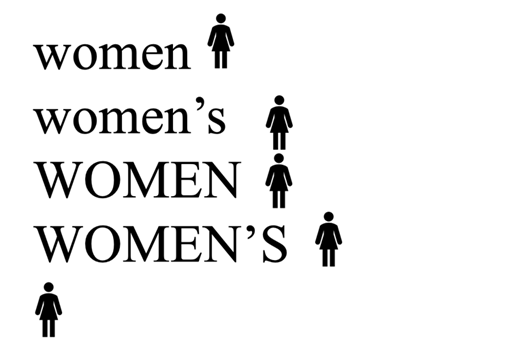

They may even be lucky enough to find this corresponding set of signs:

As these look much the same, in format, as signs for the men’s room, our aliens might reasonably guess that they both serve the same purpose. If they have further discerned anything about how people dressed in the 20th and 21st centuries, they might even recognise that these stereotyped images appear to be wearing a dress or skirt, conventionally associated with women and girls. Even if they can’t read it, they can tentatively suggest that MEN is the word for “man” and WOMEN the word for “women”, in this system. But already we see how tricky this is: they will have no inkling that both are plural.

Let us return to earth for a moment. Because Linear B is a syllabary, and not an alphabet, there are other forms of internal evidence available. This process can be illustrated in English by a word we are still inclined to decline for number and gender:

alumnus (masculine, singular)

alumni (masculine, plural)

alumna (feminine, singular)

alumnae (feminine, plural)

If we break this word down into syllables, we get:

a-lum-nus

a-lum-ni

a-lum-na

a-lum-nae

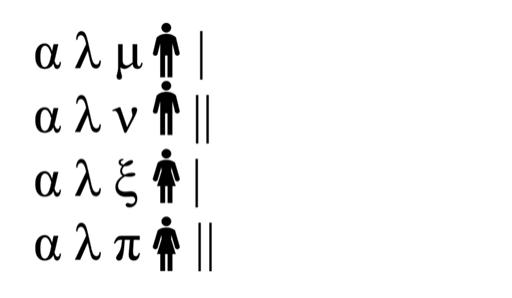

If we assign arbitrary Greek letters to each syllable, for the sake of illustration, we get:

α λ μ

α λ ν

α λ ξ

α λ π

In each case only the final sign of the word has changed, so we might perhaps think that, rather than representing completely different words, these are forms of the same word, with the ending changing to tell us something about it. This is how nouns and adjectives work in inflected languages, like Latin and Greek, and is a feature that we generally replicate for loanwords. But even though each sign stands for a complete syllable, a consonant plus a vowel, our knowledge of inflected languages will suggest to us that what is changing is not both sounds, but only the vowel: the consonant remains consistent. Each of these signs, then, belongs to the same consonant series. Even though we do not know which consonant it is, nor which vowel in each case, we can surmise that μ, ν, ξ, and π are all related. We can visualize this relationship in a grid, as so:

| Vowel 1 (u) | Vowel 2 (i) | Vowel 3 (a) | Vowel 4 (ae) | |

| Consonant 1 (n) | μ (nus) | ν (ni) | ξ (na) | π (nae) |

This is not yet much to go by: but, like the aliens puzzling out toilet signs, we have some other tricks to hand. Mycenaean records are chiefly accounting documents, and rich in numbers. These are quite obvious, being expressed by a tally system not unlike what we use today. So we might find:

α λ μ | (a-lum-nus 1)

α λ ν || (a-lum-ni 2)

α λ ξ | (a-lum-na 1)

α λ π ||| (a-lum-nae 3)

Now we know that both -μ and -ξ represent the singular, and so should belong to different genders, while -ν and -π represent plurals. Here is good evidence that we do indeed have an inflected language. But which plural goes with which singular? Luckily, we find:

Following the aliens, if we guess that the first stick figure represents a man and the second a women, it seems that -μ and -ν belong to a masculine declension, -ξ and -π to a feminine. We can even build a basic declension table:

| Singular | Plural | |

| Masculine | – μ | – ν |

| Feminine | – ξ | – π |

All of this without any idea of what the word means, or how to read it phonetically. Let us take another Latin loanword that we still treat right:

emeritus (masculine, singular)

emeriti (masculine, plural)

emerita (feminine, singular)

emeritae (feminine, plural)

Syllabified, with Greek letters again used arbitrarily:

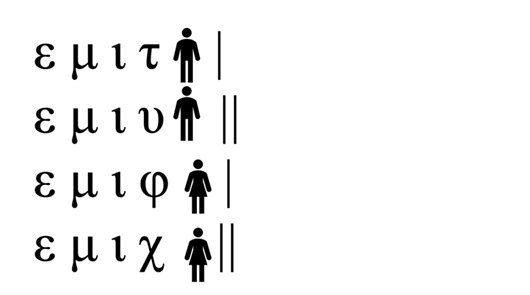

e-mer-i-tus ε μ ι τ

e-mer-i-ti ε μ ι υ

e-mer-i-ta ε μ ι φ

e-mer-i-tae ε μ ι χ

And, say we find:

Now we have the same relationship between -τ and -υ (-tus and -ti), -φ and -χ (-ta and -tae) as we did between -μ and -ν (-nus and -ni), -ξ and -π (-ta and -tae). So our grid expands:

| Vowel 1 (u) | Vowel 2 (i) | Vowel 3 (a) | Vowel 4 (ae) | |

| Consonant 1 (n) | μ (nus) | ν (ni) | ξ (na) | π (nae) |

| Consonant 2 (t) | τ (tus) | υ (ti) | φ (ta) | χ (tae) |

We are, of course, playing with the benefit of hindsight. Our examples are perfectly chosen, and we know that we are right. It was rather harder the first time round. Two words, even with examples as tidy as we have here, are no basis for a true decipherment: we must be alert to coincidence, and never shape the evidence to fit our theories. Our work so far has resembled Alice Kober’s in her demonstration that declensional patterns repeated across words and tablets, and were not phantoms but proper sport for the hunt. Tedious it was, surely, but not entirely mechanical: it took a keen eye for patterns, and a mind like a steel trap.

Only once this path had been laid could Ventris establish his grid. It relied for its accuracy on the principle of inflexion; if this was wrong, the grid would fail. But if it was right, here was a sound method. Without ever guessing what these words should mean, or what they might sound like, relationships could be established between both words and signs. It is not glamorous, nor easy, and would fail if pushed too quickly. But once built, like Cinderella’s shoe, it would only fit the one true solution.

This was the drudgery of Bennett, Kober, and Ventris. Bennett established the sign list; Kober the evidence for declension; and Ventris the grid. All that remained were the sounds, and the language itself.

Breakthrough

By February 1952, Ventris’ grid had reached its third stage, with advances made by incorporating the new evidence from Pylos. He had charted 48 signs, and of these only 7 were wrong: he had his shoe, but still needed a princess.

Much was made, and still is, of the analytical nature of Ventris’ decipherment. It was touted as a great defence against his critics: here was the solution, not of fanciful guesswork, but stubborn and methodical cryptography. As we have seen, there was indeed a great deal of method; but the neatly-placed tinder caught fire with an imaginative spark.

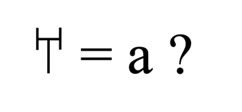

In a CV syllabary, there is one type of sign that will almost always appear at the beginning of a word: the pure vowel. As in e-me-ri-tus and a-lum-nus, it is only at a word’s beginning that we are likely to have a vowel unaccompanied by a consonant. And, indeed, there were some signs that rarely appeared later in a word than its beginning. One especially had attracted a great deal of interest, initially for its resemblance to the Minoan double axe, now for its location and frequency. It had been suggested, and Ventris decided to play with the idea, that it might represent a.

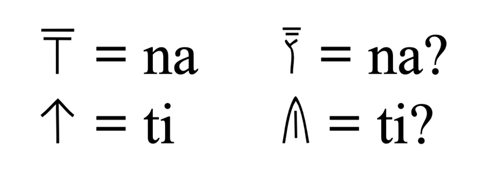

He was also toying with a few identifications based on similarities between Linear B and the later Cypriot syllabary. Though it seemed that these two systems were related, there was very limited overlap in signs, and certain aspects of the syllabary’s structure disguised that both systems were used to write the same language. But Ventris got lucky:

Adding to his confidence in the identification of na was that -n- was used in Etruscan adjectives and verbs; but the grid was foolproof, and if a guess was right it did not really matter if the reasoning was wrong. This was a point that many of his critics failed to grasp.

Because he had now placed the consonant n and the vowel i, his grid gave him the sign likely to represent ni:

But how to test the theory? The cryptographer’s greatest ally is the proper noun, which tends to be spelled out phonetically in more or less the same way no matter which writing system is in use. Even if one could not read Greek, they could have a crack at the word Ἀλέξανδρος if told that it is equivalent to Alexander: λ = l, ε = e, and so on. Difficulties appear at the end, but eight of ten letters can still be established with reasonable confidence. It was indeed the identification of the name Cleopatra in Egyptian hieroglyphs that was Champollion’s essential clue.

Now Ventris had no idea what anyone in the tablets may have been named; but even better than personal names are place names, which exhibit the same features and are often remarkably tenacious. Just northeast of Knossos is Amnisos, where Odysseus claims the winds took him while passing Cape Malea. The Odyssey-Poet places a cave of Eileithyia there, and in the 1930s Spyridon Marinatos had excavated Minoan remains at the site and identified it as the port of Knossos. This name seemed more likely than most to appear in the Knossos tablets.

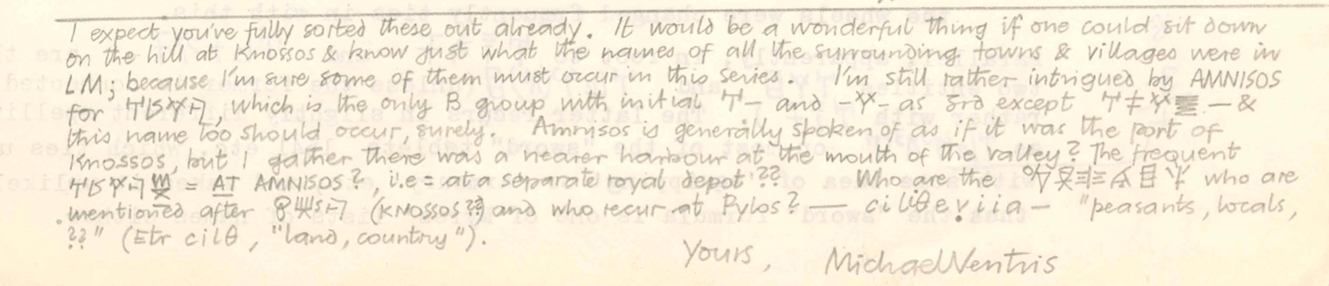

Ventris had already suggested that certain words may be place names: they were repeated frequently, in association with various commodities, but were not personal names, and did not appear at Pylos. He had floated the suggestion to John Myres in February, and could not shake it. In a letter to Emmett Bennett dated 26 April 1952, Ventris has put his foot on the right step, but not yet committed his weight:

I expect you’ve fully sorted these out already. It would be a wonderful thing if one could sit down on the hill at Knossos and know just what the names of all the surrounding towns & villages were in L(ate) M(inoan); because I’m sure some of them must occur in this series. I’m still rather intrigued by AMNISOS for a-mi-ni-so, which is the only B group with initial a– and -ni– as 3rd except a-pa–ni-x — & this name too should occur, surely. Amnisos is generally spoken of as the port of Knossos, but I gather there was a nearer harbour at the mouth of the valley? The frequent a-mi-ni-so-do = AT AMNISOS? i.e. = at a separate royal depot?? Who are the ki-ri-re-wi-ja-i who are mentioned after ko-no-so (KNOSSOS?>?) and who recut at Pylos? — ciliθeviia — “peasants, locals, ??” (Etr cilθ, “land, country”).

Yours, Michael Ventris[2]

If a and n- were right, then the top word could be read a-x-n.-x. If it were to be Amnisos, our n- sign must be ni, so a-x-ni-x. A glance at the grid would reveal that the second sign should have the same vowel as ni. In a CV syllabary, consonant clusters are always a problem, but they are sometimes resolved by ‘dead vowels’, often borrowed from a neighbouring sign. So the -mn- of Amnisos might be writing –mi-ni-. This was quite promising, and with the final sign provisionally read as so, he had his name.

From luck to rigour: by identifying mi, ni, and so, Ventris had locked in the consonant for the entire m-, n-, and s- series, and all signs with the vowels -i and -o. Any further hypotheses would have to respect these values: anything that required more than a minor adjustment here or there to account for human error would necessarily be wrong.

Another likely place name could now be half-read:

The final sign, as in a-mi-ni-so, must be so, and according to the grid each had the vowel -o. What’s more, the second sign belonged to the n-series. So this should be read: .o-no.-so. Given the principle of dead vowels already suggested, it is hard not to suggest ko-no-so: Knossos (Κνωσός). This involved guesswork, but always within the rules that Ventris had set for himself. It was never arbitrary, and if it required certain spelling rules (dead vowels, omission of final -s), then these were at least consistent.

So far, so good: but as we are merely dealing with place names, there is nothing here that is at all very Greek. But ominous clouds had appeared on the horizon. Certain words showed a variation at the end between the -o vowel and the –a vowel, which looked suspiciously like the Greek neuter declension (-on singular, -a plural; once again we must neglect the final consonant). And Kober’s triplets, too, began to look suspiciously like Greek adjectives:

These could now be read: a-mi-ni-so, a-mi-ni-si-.o, a-mi-ni-si-.a; ko-no-so, ko-no-si-jo, ko-no-si-.a. The consonant of the final sign was not obvious, but if it were j– (pronounced /y/, as in German) it might stand for a sort of glide between two vowels. This would give us adjectives of the type –i(j)os, i(j)a, perfectly formed Greek masculine and feminines (as in the word for “saint”, ayios vs ayia, in many modern Greek place names: Ayios Nikolaos, but Ayia Triada).

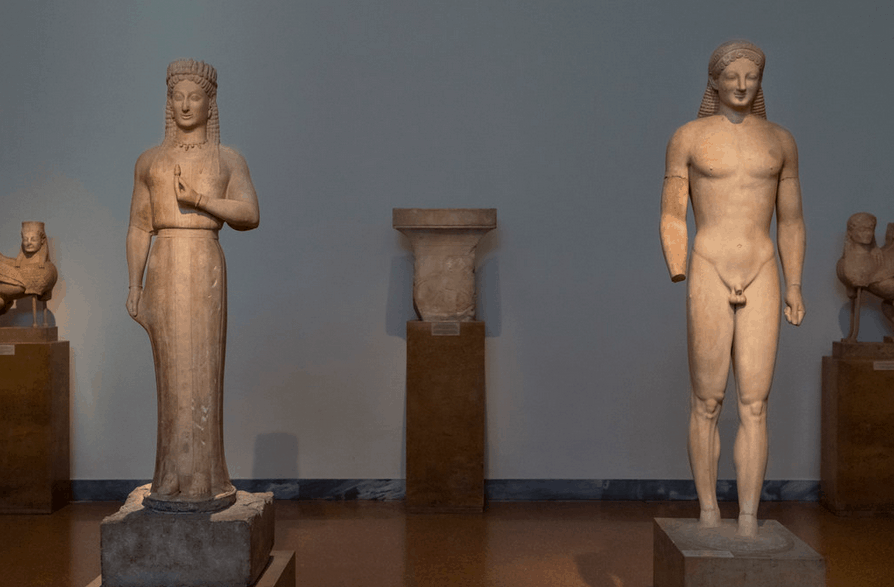

Now to search for Greek words. One of the basic items of Mycenaean vocabulary, established early by Kober on much the same principle as our aliens working on toilet signs, were the words for “boy” and “girl”:

These could be read ko-.o and ko-.a. Again, a promising variation between –o(s) and -a to distinguish masculine and feminine. As anyone who has ever visited the museums of Athens knows, a sculpture of a youthful man is called a kouros, of a woman a kore. Ventris, who had no more Greek than he had left school with and who disclaimed any philological expertise, nonetheless knew that the differences in the first syllable were the result of a disappearing consonant: the words had originally been *korwos and *korwa. The spelling was difficult, but as the final signs shared the same consonant, it was quite possible that these words should be read ko-wo, ko(r)wo(s), and ko-wa, ko(r)wa.

A great deal of the grid had now fallen into place, and the more Ventris looked the more Greek he found. Having identified the sign jo, a number of men’s names that ended in -jo-jo could now be explained as genitives (Homeric -οιο, –oio), and the w-series gave the key to the vowel u and a complicated series of archaic nouns in –eus.

This is tough stuff, and gets very technical very fast. Given the holes that remained, it is unsurprising that Ventris had his hesitations. He had entered a great catacomb with only a small torch, and it was not obvious that his light would last long enough to see him out. But, most tellingly of all, one of his great reservations reflected an error not in his method but merely his philology. This was the sign that he now had to read as qe:

This sign regularly appears after the second of two items, often accompanied by the number two, and in that respect almost certainly reflects a conjunction. Greek had a particle which served this function, but this was te (τε), not qe. What Ventris did not know was that Greek had once had the letter q (kw), but in time it had become either t or p; compare the word for “four” in Latin and Greek: quattuor vs tettara; or the indefinites qualis and poios (“of such a sort”). So qe was in fact the correct earlier form.

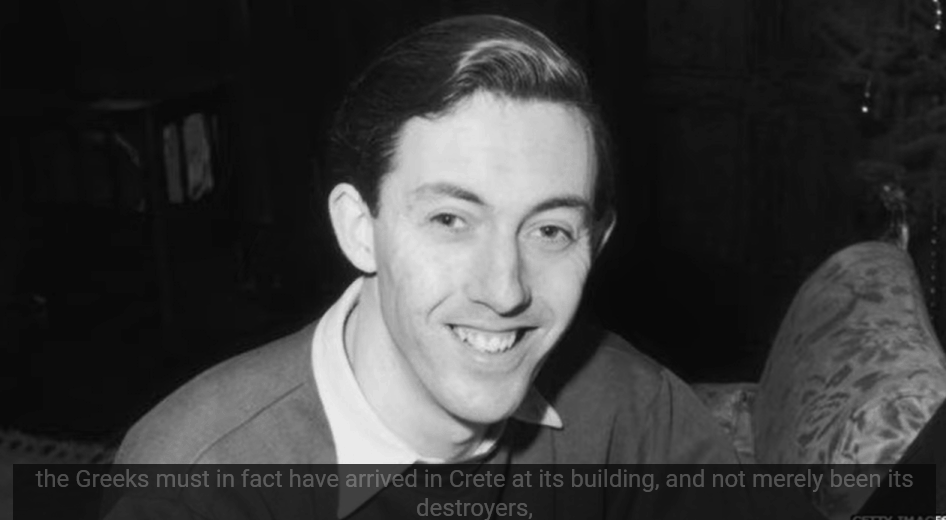

Such nagging doubts may have delayed the Work Note’s postage: in a letter to Bennett of 7 June, 1952, Ventris makes no mention of his breakthrough. It is not in fact clear when he realised that Mycenaean still preserved these labiovelars, though this discovery may be the subject of a famous anecdote. On an “evening early in June”, he and his wife Lois had invited over Michael Smith, a fellow architect, and his wife Prudence, who had just completed her degree in Literae Humaniores at Somerville College, Oxford. Lois was left to play the host, plying the guests with sherry, while Michael remained at work rather longer than the rules of good hosting would dictate. At last he emerged from his study, too excited properly to be bashful: “I know it, I know it, I am certain of it.” Over dinner he shared the topic of his certainty, and afterwards took the Classicist Prudence into his study to share his notes and findings.

It is not clear what, exactly, prompted his certainty on that evening. Nor even can we be sure quite what evening it was; but so long as “early June” is right, it must have been after Work Note 20 was completed. But by 18 June, when he finally shared the decipherment with Bennett, he had given 𐀤 the value pe, which represents a possible reflex of the labiovelar in later Greek. A possible explanation for one of his sticking points in Work Note 20 may well have been the tipping point.

Whatever his breakthrough, Prudence, who knew more Greek than Ventris, was quickly convinced by what she saw, and became an important proselytizer for the decipherment. After her degree she had taken a job with the BBC, and by her fervour convinced her rather sceptical colleagues that Ventris should announce his decipherment on the air. And so he did, on the first of July:

During the last few weeks, I have suddenly come to the conclusion that the Knossos and Pylos tablets must, after all, be written in Greek: a difficult and archaic Greek, seeing as it is 500 years earlier than Homer, and written in a rather abbreviated form; but Greek nonetheless.

This is not how most would have made the announcement. Here was a great claim, sure to be controversial, presented publicly without supporting evidence. Many listeners no doubt dismissed it. But at Oxford a young philologist named John Chadwick heard digammas where he expected them, and wanted a closer look.

A helping hand arrives

Chadwick (1920–98), the son of a civil servant, had been educated at St Paul’s School, where he was a classmate of Kenneth Dover (1920–2010), before going up to Corpus Christi, Cambridge in 1939. War and the fall of France soon intervened, and he enlisted with the Royal Navy; but in 1942 he was swept away to Alexandria and secret intelligence work, where he did not limit his efforts to the codes he was supposed to break, rather to the embarrassment of some at Bletchley Park. After the Italian surrender he joined that team, where he had to learn much Japanese technical vocabulary relating to submarines. Through this process he learned a great deal about how codes are broken, and how a decipherment might grow from a few words to an entire message.

At Bletchley he also met James Wyllie, one of the editors of the Oxford Latin Dictionary.[3] After completing his degree in 1946, Wyllie – about whom there is a very different story to tell one day – would offer him the job that he needed to marry his wartime sweetheart Joan Hill in 1947. He would stay in this post until 1951, when Arthur Beattie left Cambridge for the Greek chair at Edinburgh and Chadwick was appointed to his old position.

And so it was that he was preparing a course of lectures on the Greek dialects when he heard Ventris’ announcement – another of history’s happy accidents. After the war ended, he had, with friends, tried his hand at Linear B, but found that too little had been published. Since moving to Oxford he had been in touch with Myres, from whom he was able to acquire a copy of Work Note 20. He didn’t expect much, but soon found that Ventris’ suggested values produced, like a half-broken wartime code, islands of sense in a sea of confusion.

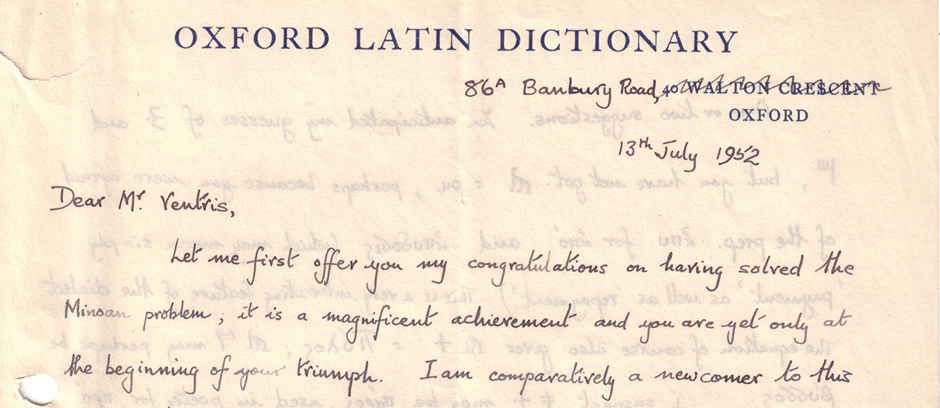

In the meantime Myres had told Ventris of this interested new party, and Ventris soon wrote to Chadwick, suggesting rather modestly that “if you find any points of contact between your work and mine, it would be very interesting to have to the opportunity of exchanging views.” Chadwick’s response has become rather famous:

Dear Mr. Ventris,

Let me first offer you my congratulations on having solved the Minoan problem, it is a magnificent achievement and you are yet only at the beginning of your triumph…

The advantage of Chadwick’s philological acumen was immediately on display. Two sign groups, one a place name very common at Pylos and the other apparently a prefix, had resisted Ventris’ efforts:

The problem was the sign 𐀢: the consonant had to be p-, but the vowel remained obscure. If given the value pu, then the first group could be read as pu-ro, Πύλος (Pylos), a name still missing. But then the second group, which one might rather want to read as later Greek ἀπο- (apo, “from”) must be the rather strange a-pu, ἀπυ-. Ventris’ thoughts on the matter are not recorded, but Chadwick knew that in certain dialectal inscriptions one found ἀπύ (apu) in place of Attic ἀπό (apo). This was quite remarkable confirmation: at one stroke both the name Pylos and a common preposition were both restored. It is little wonder that Chadwick was so readily and eagerly convinced.

His enthusiasm proved salutary. Ventris had stepped quite boldly to the edge of a cliff, and only in doing so realised just how precipitous was the drop:

Dear Mr Chadwick,

Thank you very much for your letter. It is very encouraging to hear from someone who has been working on the Minoan problem that they agree with the Greek approach; because frankly at the moment I feel rather in need of moral support. The whole issue is getting to the stage where a lot of people will be looking at it very skeptically, and I’m conscious that there’s a lot which so far can’t be very satisfactorily explained. There’s a kind of central area of sense, but still a great periphery which is baffling.

New evidence provides a handle:

Still, there was some cause for hope. Blegen’s excavations at Pylos, abandoned after 1939 with the onset of the War, had resumed that summer, and 400 new tablets were found. These, which Ventris had never seen, would provide an independent check on his work: “I feel sure that if there’s something in this vocabulary, then there should be pretty clear confirmation of it in the new material.”

And so Ventris sent his sign-list to Blegen, but did not remain idle. He had already reached out to the Journal of Hellenic Studies as a possible venue for the publication of his decipherment, and asked Chadwick to collaborate on the article. Two drafts, one meeting in Cambridge, and a great deal of cautious criticism later, the manuscript of “Evidence for Greek Dialect in the Minoan Archives” was sent to the JHS for typesetting in early November 1952. The result was, in the words of Rhys Carpenter, “highly condensed, almost unreadable, barely comprehensible, but thoroughly sensational.”

The central contention of “Evidence” was framed modestly but not without confidence: “A complete decipherment is still a long way off; but we hope to produce sufficient evidence to show that we are dealing with a true Greek dialect.” But in the time between its submission in November of 1952 and publication in the summer of 1953, Blegen and the 1952 tablets had entered the picture with dramatic results.

Linear B tablets were not written for posterity. Inscribed on moist clay, they were left to dry and filed away for a year, it seems, or two: never more. It is only by a historical irony that they are preserved at all, baked hard by the very fires that destroyed the palaces. Though the archive rooms at Pylos give no sign of deliberate ransacking, the collapse and conflagration of the building was hardly gentle on the tablets inside. Many were found broken, with a thick covering of hard lime, further souvenir of the fire, obscuring the signs. So it was that none of the tablets found in 1952 could be read before significant conservation work. This was accomplished over the winter of 1952–3, and no one saw them in those long months except the museum staff engaged in this task. But in March of 1953, Blegen returned to Athens, and was able to investigate the newly cleaned and mended tablets.

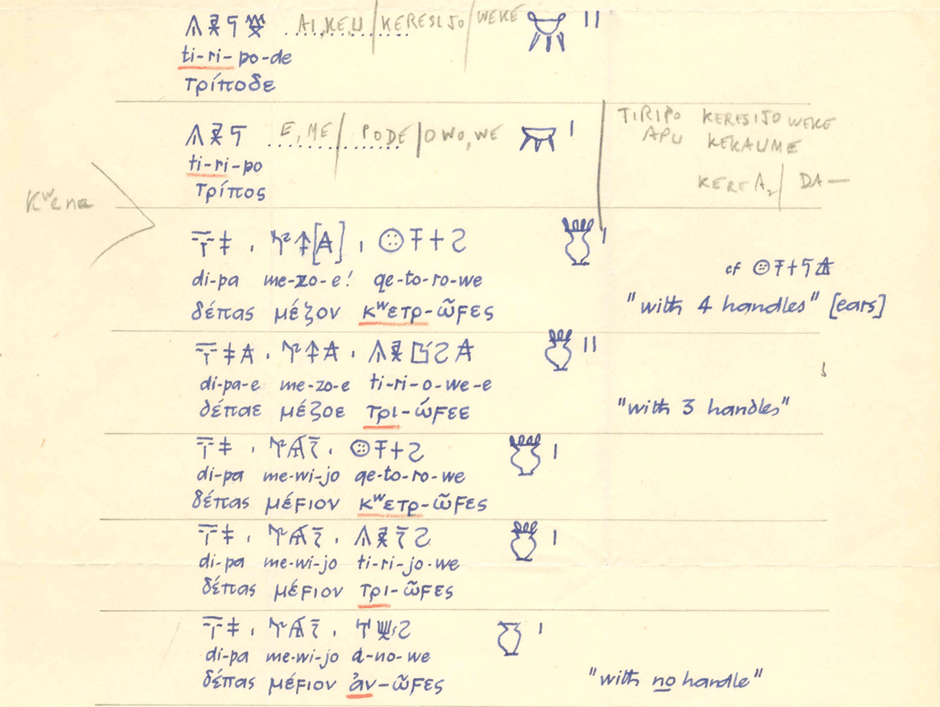

With Ventris’s proposed values in hand, a tablet that had been found in two halves that June caught his eye:

He wrote to Ventris:

Enclosed for your information is a copy of P641, which you may find interesting. It evidently deals with pots, some with three legs, some with four handles, some with three, and others without handles. The first word seems by your system seems to be ti-ri-po-de and it recurs twice as ti-ri-po (singular?). The four-handled pot is preceded by qe-to-ro-we, the three-handled by ti-ri-wo-we or ti-ri-jo-we, the handleless pot by a-no-we. All this seems too good to be true. Is coincidence excluded?… I should like to hear what you make of this inscription.

Ventris was not normally an excitable man, but this did the job. He called Chadwick immediately to share the news, and though his modesty was not quite overcome, but he now held such evidence that all, in Chadwick’s later words, “who were unprejudiced could now be convinced that the system worked.”

The confirmation that it offered was in the form of the remarkable agreement between the proposed Greek values and the illustrations. Next to a picture of a three-footed vessel and the numeral two was the word ti-ri-po-de, quite transparently the Greek plural tripodes (τρίποδες), “tripods” – literally “three feet”. [4] And, if we doubted the declension, next to a three-footed vessel with the numeral one, ti-ri-po, the singular tripos (τρίπος; cf. Attic τρίπους).

A vessel with four handles is called qe-to-ro-we. The first element is the numeral four (kwetr-; cf. Latin quattuor, Attic tettares, τέτταρες after *kw– > t-), the second a form of the word “ear”, already in Homer used of the handles of vessels. And so kwetrowes = “four-handled”. [5] Finally, our handleless vase is called a-no-we, where an- is the negative prefix (equivalent to English “un-”, Latin in-): “no-handles”.[6]

To these we may add the frequently recurring di-pa, plausibly enough δέπας, a Homeric word for a cup or goblet, and the adjectives me-zo (mezos, μέζως) and me-wi-jo (mewios, μεϝίως), “larger” and “smaller” respectively.[7] Ventris had hoped for clear confirmation from Blegen’s new material; here was something to exceed any reasonable expectation.

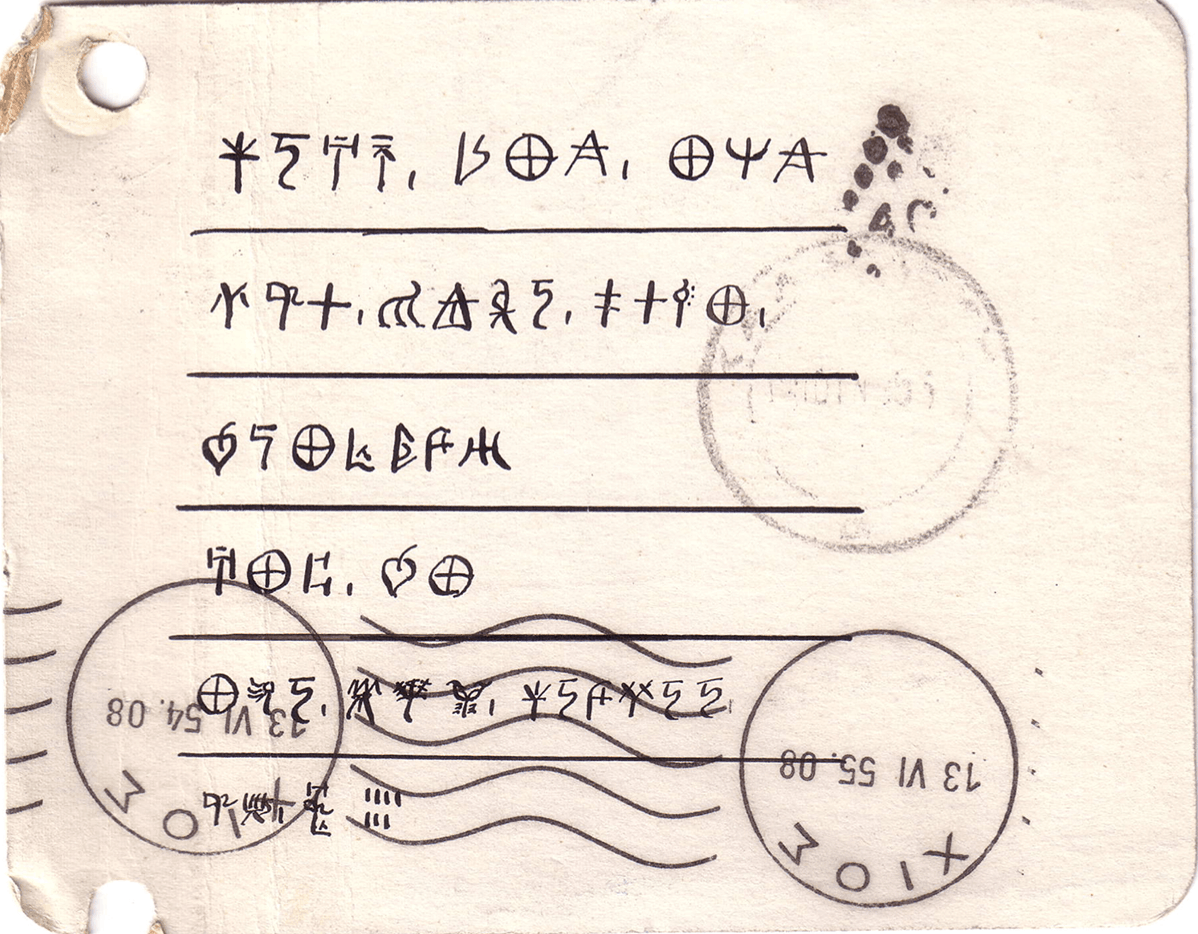

From 1953 to 1956 Ventris was in high demand: the Institute of Classical Studies founded its Mycenaean Seminar; the first international colloquium on Mycenology (as the discipline came to be known) was held at Gif-sur-Yvette, south of Paris; and time had to be made for a visit to Buckingham Palace to receive an OBE from the Queen. And all the while there was writing to be done: he worked closely with Chadwick on Documents in Mycenaean Greek, which remains unsurpassed in its breadth and ambition to make the technical details of the tablets intelligible to the educated reader.[8] Chadwick delivered the typescript to Cambridge University Press in July 1955. Ventris was in Greece, and so had to be notified by postcard – written in Linear B. The script could not just be read again: it could be written, and after 3,000 years given the breath of new life.

i-jo-a-na mi-ka-e ka-re-e

sa-me-ro pu-pi-ri-jo pa-ro-do-ka

tu-po-ka-ra-pe-u-si

a-ka-ta tu-ka

ka-mo-jo ke-pu2-ra3 i-jo-u-ni-jo-jo

me-no A-ME-RA 7

John to Michael: Greetings!

Today I have given the book

to the typesetters.

May it go well for us!

At the Bridge of Cam, on day 7

Of the month of June.

But Ventris would not see the book published. Early in the morning of 6 September, 1956, he collided with a parked lorry while driving and was killed instantly. He was 34: ὃν οἱ θεοὶ φιλοῦσιν ἀποθνῄσκει νεός.[9]

It is on this sad note that the story of the decipherment tends to end. And it is true that, with the publication of the Tripod Tablet in 1954, Ventris’ work won wide (though not universal) acceptance. In many ways the work that has followed since was of a different sort. The basic values of the core signs were known. The great challenge was now interpretation – and this continues today. So, too, does the decipherment: rare signs, often restricted to personal names or toponyms, still defy a fixed phonetic value. New finds are still made, though slower than many would like, and our understanding of these terse and archaic documents evolves with our understanding of the Mycenaean world more broadly.

Theodore Nash is a PhD student in Classical Archaeology at the University of Michigan. He has previously written for Antigone about Greek scholarship at Oxford between the Wars.

Further Reading

The debt that this essay owes to previous work will be obvious to all who read it, even presented as it is without a traditional scholarly apparatus. To render that debt explicit, and as a guide to the curious, I include this list of suggested reading.

Correspondence and Historical Documents

The Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory at the University of Texas has digitised a significant collection of letters between many of the principal actors in the story of decipherment, including Michael Ventris, Alice Kober, Emmett Bennett, John Chadwick. These can all be found here. The value of this resource cannot be expressed without resort to rather dramatic hyperbole. A few letters, including Chadwick’s first letter to Ventris, have been digitised by the Faculty of Classics at the University of Cambridge.

None of this correspondence has been published systematically, though it is frequently quoted and reproduced in biographical and historical studies (for which see below). The few publications focussed on correspondence are:

Lisa M. Bendall, The Decipherment of Linear B and the Ventris-Chadwick Correspondence (Fitzwilliam Museum Catalogue, Cambridge, 2003. (Images of many letters are reproduced, but unfortunately not in very high quality.)

Rupert Thompson, “The Ventris–Chadwick Correspondence and the Decipherment of Linear B: A Denier, A Dissenter and A Dubious Conclusion,” Cambridge Classical Journal 65 (2019) 173–99.

Ventris’ Work Notes were compiled and published by Anna Sacconi, Work Notes on Minoan Language Research and Other Unedited Papers (Edizioni dell’Ateneo, Rome, 1988.They are invaluable for anyone working on the history of the decipherment, but do not make for light reading. Included are also a few letters from and to Ventris, and the text of his full radio announcement. The actual announcement can be heard here.

Biographies

Both Ventris and Kober have been the subject of biographies in the past twenty years. These were written by journalists, not scholars, with the advantage that they are generally accessible and affordable, but they can tend towards the speculative or sensational. They are both very valuable when taken cum grano salis:

Margalit Fox, The Riddle of the Labyrinth (Profile Books, London, 2013). (Tracy 2018 offers a valuable rebuttal to the claims that Blegen deliberately kept Pylos material from Kober.)

Andrew Robinson, The Man who Deciphered Linear B (Thames and Hudson, London, 2005). (Best read with Lisa Bendall’s JHS review.)

Accounts of the Decipherment

Ventris never produced a full account of his own process (which explains, inter alia, why we do not know how he worked out the labio-velar series). After his death, the task of explaining and defending his friend’s work was left to Chadwick, who produced the first and still best account of the decipherment. Anyone who has read this far should probably find themself a copy: John Chadwick, The Decipherment of Linear B (Cambridge UP. 1958, 2nd ed. 1967).

The Crunchy Stuff

All of the above was written for the curious but Greekless reader. Those with Greek may enjoy Documents, though its age and stages of revision make it a difficult first introduction. The best introduction to Linear B in English is the three-volume Peeter’s Companion, aimed (and, unfortunately, priced) for academics: Yves Duhoux & Anna Morpurgo-Davies, A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and Their World (3 vols, Peeters, Louvain, 2008–14).

Those looking for something cheaper will find much value in Hooker’s Introduction. Though dated, it remains the most concise and convenient introduction to the grammar of Mycenaean Greek: J.T. Hooker, Linear B: An Introduction (Bristol Classical Press, 1980).

Notes

| ⇧1 | All three scripts are related, though the corpus of Cretan Hieroglyphic (CH) is so small that very little can be said with certainty. In basic terms, Linear A has many signs that look like more schematised versions of CH signs, and it probably developed from that script, although both remained in contemporary use for a period. It is not possible to say whether they both record the same language, though it is almost certain that the language of Linear A, at least, was a non-Indo-European language. Linear B is not strictly a separate script from Linear A, but rather the result of orthographic and administrative reorganisation when it became necessary or desirable to write in Greek rather than the unknown ‘Minoan’ language. |

|---|---|

| ⇧2 | He has in fact already come a long way here, as Etruscan ciliθeviia is a nearly-enough plausible reading of the sequence ki-ri-te-wi-ja-i. |

| ⇧3 | Chadwick maintained an interest in lexicography for the rest of his life, the fruits of which include the Supplement to LSJ and, by way of a former student’s piety, the Cambridge Greek Lexicon, about which you can read more here. |

| ⇧4 | Alternatively, τρίποδε, the archaic dual declension that referred exclusively to two of something. |

| ⇧5 | There is quite a remarkable parallel for this in the Homeric Iliad (11.632–4): δέπας… οὔατα δ’ αὐτοῦ τέσσαρ᾽ ἔσαν, “a depas of four ears/handles.” The plural -ῶες for οὔατα is defensible etymologically and attested in Theocritus’ ἀμφῶες (1.28) of a two-handled vessel (lit. “on both sides”). |

| ⇧6 | Also supported by Theocritus (Ep. 4. 3), who has the adjective ἀνούατος, “un-handled”. |

| ⇧7 | Cf. historical μείζων and μείων. |

| ⇧8 | Today it is generally the second edition of 1973, made necessary by the rapid development of the discipline in its first two decades, to which scholars turn. It is of course outdated: but not obsolete. |

| ⇧9 | “He whom the gods love dies young.” |