rotten > Library > Medicine > tDCS

tDCS

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation

Ingredients:

Ingredients:

One (1) brain, inside skull

One (1) 9-volt battery

Two (2) wires

Two (2) damp sponges

Instructions:

Attach battery to wires, attach wires to sponges, attach sponges to skull, one over each eyebrow. Simmer once a day until mental health reaches a firm consistency.

It sounds like something you dreamed up in the basement with your stoner friends in high school. (In fact, you may actually have done so.) But transcranial direct current stimulation is the hottest thing to hit the improvisational health management scene since acupuncture. A growing body of evidence suggests that sticking a battery onto your head could hack into your brain's operating system and make life generally more worth living. Think of it as Norton Utilities for the mind.

That's not an oversimplification of the process. tDCS is literally that simple. The total cost of a treatment is less than $5 of parts from Radio Shack and a sponge. No prescription needed. No needles, no pills, no insurance companies, no weird hormonal fluctuations, no commercials saying "I'm glad [drug of choice] has a low risk of sexual side effects!"

An analysis of the pros and cons of tDCS yields fairly impressive results.

| PROS

Improved hand-eye coordination

Better memory

Less depression

Recover from brain damage

Less senility

Me talks nice like teacher

Better memory

Control seizures

Cure migraines

Become superior human, crush puny unenhanced inferiors, survive apocalyptic "rise of the machines"

Better memory

|

CONS

Could end up looking stupid

Small, but not entirely absent, chance of permanent brain damage

|

Let's face it, there's a reasonably good chance you're going to end up looking stupid even without the battery stuck to your head. Especially after the rise of the machines.

Let's face it, there's a reasonably good chance you're going to end up looking stupid even without the battery stuck to your head. Especially after the rise of the machines.

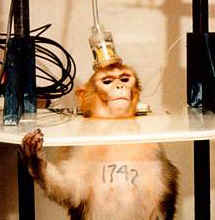

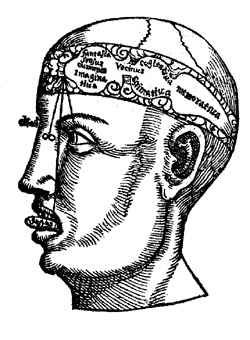

The therapeutic art of applying electricity and other traumas to the brain has a long and mostly unpleasant pedigree, with most treatments being the medical equivalent of kicking the jukebox in order to make it play a tune, except that the jukebox trick works about 99 times more often as most treatments used to hack brain functions. Electroconvulsive therapy—aka electroshock—is a hacking technique more consistent with Jason Voorhees than Kevin Mitnick. ECT applies up to 500 volts of electricity to the entire brain. But as everyone knows, it's not the voltage that kills you, it's the amperage—between 200 and 1600 milliamps. By comparison, tDCS applies a trivial nine volts of electricity with an amperage generally not in excess of two milliamps.

For an ECT treatment, patients are strapped to a table, with special salves applied to prevent their skin from burning, and gagged to prevent them from biting off their tongues. In contrast, a patient receiving a tDCS treatment could literally perform brain surgery on another patient during the procedure with only a slight tingling sensation to distract him or her.

For an ECT treatment, patients are strapped to a table, with special salves applied to prevent their skin from burning, and gagged to prevent them from biting off their tongues. In contrast, a patient receiving a tDCS treatment could literally perform brain surgery on another patient during the procedure with only a slight tingling sensation to distract him or her.

The main reason that tDCS has become the latest rage in alternative medical treatment is precisely because it's so innocuous. The voltage is so low that it's (almost) impossible to do any harm. As far as anyone can tell, patient their nothing to lose except their dignity, and most patients with brain problems have already been forced to make compromises on that front.

Although the technique in tDCS is extremely simple, its actual effect is complicated to the point that no one can really say exactly what it does to the brain, an organ which scientists recently discovered is very, very complicated. It seems to work better when applied during sleep. (Very probably.) It may reverse or moderate the extremes found in bipolar disorders, as well as reversing the electrical polarity of neurons. (Which is different.) (We think.) It also seems to moderate the extremes of brain seizures—when an electrical storm sweeps over the neural circuitry that powers consciousness. (We're pretty sure.)

Although its negatives are few, most of the positives are disputed to a greater or lesser extent. Studies have found that tDCS may or may not offer one or more of the following benefits:

- If you strap on the battery and set a timer so that the voltage kicks in during the deepest levels of sleep, tDCS improves both visual and verbal memory function. Some studies found enhancments in memory for waking patients as well, though others have delivered conflicting results.

- On the bright side, studies have repeatedly found that tDCS can change in brain characteristics such as blood flow distribution, electrical polarity and motor response. Unfortunately, these changes are often of debatable value, and the changes caused by tDCS are more akin to shuffling playing cards than building a house of them—you can cause a general wave of activity with reasonably predictable parameters, but it doesn't guarantee a precise result.

- Numerous studies have also found that the changes caused by tDCS can have a lasting and possibly even permanent effect. So if you shuffle the deck well, you can enjoy a prolonged lucky streak. Unfortunately, that also means that negative effects—such as susceptibility to migraines in certain cases—will persist.

- tDCS can be used to moderate the negative side effects of psychoactive drugs and to enhance the effects of other brain-shaping technologies like transcranial magnetic stimulation.

- Depending on the polarity of the connections, tDCS can be used to adjust the "contrast" setting in human vision, as well as to enhance or suppress the ability to visually detect small movements. The treatment appears to be reversible in these cases, offering the prospect of a "Display Settings" control panel for your brain.

- For those suffering from persistent itchiness or chronic pain, tDCS can depress tactile sensitivity.

- tDCS is currently under study for the treatment of dementia, seizures, memory-related disorders and generally any problem that involves a brain locked in a pattern of misfires—from depression to tinnitus. There have been no studies yet on whether tDCS can dislodge an annoying commercial jingle from your head, but there is reason to hope.

All these treatments make use of a brain quality known as neuroplasticity, a metaphor for mental and neural activity that equates the brain's operating system to a lump of putty that can be squeezed and stretched into different configurations. Early research into neuroplasticity resulted in gross insults to the brain, whether via lobotomy or ECT. More recent work has focused on TMS—a form of magnetic stimulation which causes all the neurons in the brain to simultaneously fire in the same direction, a process vaguely analagous to rebooting your computer, except that your computer isn't likely to spontaneously develop seizures after rebooting. tDCS is a gentler approach. It nips and molds around the brain's outer edges rather than flattening the putty with a sledge hammer before attempting to roll it back into its original shape.

All these treatments make use of a brain quality known as neuroplasticity, a metaphor for mental and neural activity that equates the brain's operating system to a lump of putty that can be squeezed and stretched into different configurations. Early research into neuroplasticity resulted in gross insults to the brain, whether via lobotomy or ECT. More recent work has focused on TMS—a form of magnetic stimulation which causes all the neurons in the brain to simultaneously fire in the same direction, a process vaguely analagous to rebooting your computer, except that your computer isn't likely to spontaneously develop seizures after rebooting. tDCS is a gentler approach. It nips and molds around the brain's outer edges rather than flattening the putty with a sledge hammer before attempting to roll it back into its original shape.

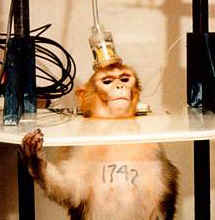

As for the do-it-yourself crowd, the technology of tDCS is pretty basic. Anyone who grew up with the Radio Shack 100-in-one science experiment kit can build a working tDCS stimulator. However, hacking the brain itself contains some inherent risks.

If you opened up your computer and randomly connected available circuits, you might discover an interesting new effect, but it's far more likely you would completely fry your motherboard.

The brain is much more resilient than your computer, and tDCS is much less intrusive than randomly rewiring live circuits. But if your experiments end up giving you a permanent facial tic, a lasting case of impotence, or your dog starts talking about the Antichrist, don't come crying to us.

Pornopolis |

Rotten |

Faces of Death |

Famous Nudes

|

Ingredients:

Ingredients:

Let's face it, there's a reasonably good chance you're going to end up looking stupid even without the battery stuck to your head. Especially after the rise of the machines.

Let's face it, there's a reasonably good chance you're going to end up looking stupid even without the battery stuck to your head. Especially after the rise of the machines. For an ECT treatment, patients are strapped to a table, with special salves applied to prevent their skin from burning, and gagged to prevent them from biting off their tongues. In contrast, a patient receiving a tDCS treatment could literally perform brain surgery on another patient during the procedure with only a slight tingling sensation to distract him or her.

For an ECT treatment, patients are strapped to a table, with special salves applied to prevent their skin from burning, and gagged to prevent them from biting off their tongues. In contrast, a patient receiving a tDCS treatment could literally perform brain surgery on another patient during the procedure with only a slight tingling sensation to distract him or her.

All these treatments make use of a brain quality known as neuroplasticity, a metaphor for mental and neural activity that equates the brain's operating system to a lump of putty that can be squeezed and stretched into different configurations. Early research into neuroplasticity resulted in gross insults to the brain, whether via

All these treatments make use of a brain quality known as neuroplasticity, a metaphor for mental and neural activity that equates the brain's operating system to a lump of putty that can be squeezed and stretched into different configurations. Early research into neuroplasticity resulted in gross insults to the brain, whether via