|

War of the Worlds It is perhaps a comment on the idiocy of human beings that one of the biggest hoaxes to panic the American public began with the following words:

It is perhaps a comment on the idiocy of human beings that one of the biggest hoaxes to panic the American public began with the following words:"The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air in a radio play by Howard Koch suggested by the H.G. Wells novel 'The War of the Worlds.'" On the face of it, this seems like a pretty straightforward concept. It's a radio play, based on a novel, featuring one of the most recognized voices in the history of radio. AND IT WAS THE DAY BEFORE HALLOWEEN! Despite all these seeming clues, despite the fact that the novel was a well-known classic, despite the fact that a commercial break halfway through the one hour radio program specified "You're listening to a CBS presentation of Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the air in an original dramatization of 'The War of the Worlds' by H.G. Wells," despite the fact that the story being depicted was about MARTIANS INVADING THE EARTH, the radio play sparked a panic of unparalleled proportions. Presented in a series of mock news reports, "War of the Worlds" was a production by radio and theater wunderkind Orson Welles, who had not yet made the leap to Hollywood. Welles had already made a name for himself as a brilliant maverick on Broadway and he had become a household name as the voice of "The Shadow," a pulp-fiction crime fighter who "knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men." Only 23 years old and already a household name, Welles had extended his theater troupe to CBS radio with a weekly program featuring the players of his "Mercury Theater." Welles had successfully adapted "A Tale of Two Cities," "Julius Caesar," "Dracula," and "Treasure Island" when he decided to take on "War of the Worlds." Interestingly, no one freaked out when they heard Caesar had been killed.

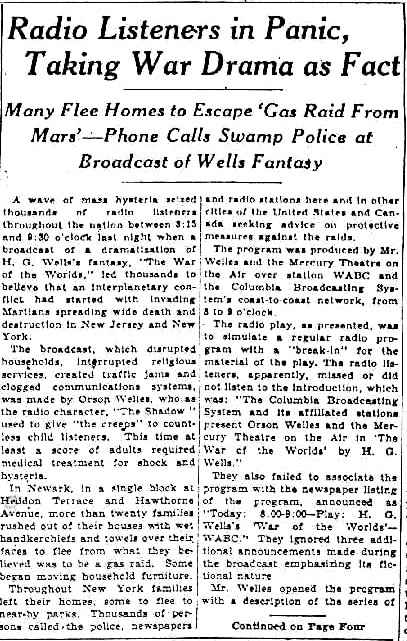

The lead story in the New York Times the next day had the headline "Radio Listeners in Panic, Taking War Drama as Fact; Many Flee Homes to Escape 'Gas Raid From Mars' Phone Calls Swamp Police at Broadcast of Wells (sic) Fantasy." This would be the first and last time that the New York Times ever featured the phrase "Gas Raid From Mars" in a headline. The story read: "A wave of mass hysteria seized thousands of radio listeners between 8:15 and 9:30 o'clock last night when a broadcast of a dramatization of H. G. Wells's fantasy, 'The War of the Worlds,' led thousands to believe that an interplanetary conflict had started with invading Martians spreading wide death and destruction in New Jersey and New York." It was an unprecedented event in modern history. According to some accounts, the trouble stemmed from a related popular radio broadcast on another channel, which featured an unpopular musical segment at 8:12 p.m., prompting thousands of people to twirl the dial in the 1938 version of channel-surfing. These listeners had not heard the opening passage quoted above, nor the subsequent "This is Orson Welles" introduction of the play. Instead, they tuned in just in time to hear an news update that the Martians were running wild over New York and New Jersey (most of the panic was centered there, although the broadcast was heard nationwide).

The freakouts that followed were a cautionary tale about the power of the newly emerging instant news media, not to mention being pretty funny. According to the New York Times, the Associated Press, newspapers and the police were quickly notified that the panicked people calling them were misinformed. But there were plenty of people who couldn't get through, or those who simply didn't bother trying. Playgoers stampeded out of a theater in New York City when two members of the audience were paged by their panicked wives, who called to relay the story. The New York Times itself recorded 875 calls from panicked listeners. In Harlem, dozens of people rushed into the police stations to say they had packed for evacuation and to ask where they should go. Churches were filled with people who had come to make their peace with God in light of the impending end of the world. As people fled their homes into the streets and gathered in public places, the initial radio broadcast gave way to a whispering campaign, as frenzied people repeated and further garbled the story. After the police switchboards in Manhattan were overloaded with callers, a dispatch actually went out over the radio informing officers that New Jersey was being bombed. Thousands of calls were fielded by police operators in different New York and New Jersey precincts, some even refusing to believe that the reports were fiction after they were told. City politicians and officials in Newark started trying to organize emergency plans. A team of scientists set out from Princeton to take samples of the "meteor" which had fallen on the town. Screaming people evacuating Newark caused a massive traffic jam in the center of town. The New York Times reported that more than a dozen people had to be treated and in some cases, sedated due to hysteria. While mostly centered around the area where the "Martians" were dealing death and destruction with uncanny "heat rays," the rest of the nation reported similar idiocy, with newspapers and police stations bearing the brunt of the panic. One woman called the Boston Globe to tell them she could "see the fire." The Times, quoting an AP report, said that a Pittsburgh man came home to find his wife on the verge of downing a bottle of poison, rather than deal with the whole death ray thing.

Welles didn't help matters much. Basking in his sudden notoriety, he flashed his trademark mischievous grin and twinkled his trademark twinkling eye as he assured everyone that the panic was completely unintentional and that he was really very sorry. Welles was an inveterate showman and he liked getting people wound up. Whether or not it had been done on purpose, it was pretty clear pretty quickly that he was delighted at how things turned out. While you should never say never, it's unlikely that America will ever see a scare quite like that one again. Aside from causing a large percentage of the American population to become instantly jaded about what they hear on the radio, the changed complexion of the news and media industry makes it pretty unlikely that anyone these days would respond to just one report of a disaster. And since the new national response to emergencies is to sit in your living room glued to CNN, rather than rushing out to a church, it's not like a lot of harm would be done anyway...

|

The radio play was a clever modernization of the original story. At 8 p.m., Oct. 30, 1938, faux music program began, only to be interrupted by melodramatic news updates, accented by sound effects and music. While not a typical presentation, it was also pretty obviously not a real news broadcast. Nevertheless, the population of America had a bad case of the pre-

The radio play was a clever modernization of the original story. At 8 p.m., Oct. 30, 1938, faux music program began, only to be interrupted by melodramatic news updates, accented by sound effects and music. While not a typical presentation, it was also pretty obviously not a real news broadcast. Nevertheless, the population of America had a bad case of the pre- The "sensible" people picked up their phones and called the newspapers, the radio station or the police. So many "sensible" people did this that the phone lines became miserably jammed, reinforcing the notion that something had really happened.

The "sensible" people picked up their phones and called the newspapers, the radio station or the police. So many "sensible" people did this that the phone lines became miserably jammed, reinforcing the notion that something had really happened.  In the aftermath of the broadcast, Americans were in stages appalled, depressed, embarrassed and pissed off about the whole thing. Mostly pissed off. Many of the people who had panicked blamed Welles for the fiasco, rather than their own gullibility or their failure to listen to the four separate instances in which the hourlong broadcast repeated that it was a fictional dramatization.

In the aftermath of the broadcast, Americans were in stages appalled, depressed, embarrassed and pissed off about the whole thing. Mostly pissed off. Many of the people who had panicked blamed Welles for the fiasco, rather than their own gullibility or their failure to listen to the four separate instances in which the hourlong broadcast repeated that it was a fictional dramatization.