|

Singularity That singular sensation you're feeling is the very fabric of spacetime disintegrating around your ears.

That singular sensation you're feeling is the very fabric of spacetime disintegrating around your ears. If you ask an astrophysicist what a singularity is, he'll likely say it's a point in space where matter has become infinitely dense and the resulting gravitational field has dramatically warped space and time. If you ask a mathematician what a singularity is, he'll tell you it's an uncomputable point for which you can compute all the surrounding points. It's the hole in the piece of graph paper. These two definitions mean pretty much the same thing, but neither conveys how a singularity epitomizes the mind-bending funhouse atmosphere of the collective oxymoron we laughably refer to as "reality." The physical idea of a singularity is intimately tied to the mathematical concept. An uncomputable point in space invariably represents the most extreme conditions known to science. Singularities are arguably the best available evidence that the universe is made out of math, because it appears that reality breaks down at the same place that math breaks down. Around the start of the 20th century, people began to realize that the universe was a lot weirder than previously thought. Physicists began to speculate about what would happen when a dying star collapsed, and in 1939, J. Robert Oppenheimer and Hartland Snyder put forward a model of the star collapsing to a "single point"—compacting to infinitesmal size and reaching a measurement of density which is mathematically infinite, at which point the equations to describe the interior of the object break down, creating a singularity.

Science fiction writers and physicists have speculated that black holes might be a gateway to other universes, parallel worlds, higher dimensions or some commbination of all three. In sci-fi, this theory offers the possibility of cheerful jaunts in which daring adventurers somehow fly their spaceships through the event horizon and pop out on the other side, ready to explore strange new worlds.

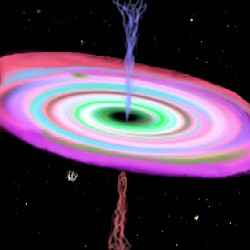

Anything that falls into the event horizon is gone forever, pulverized into a subatomic paste and trapped in a web of frozen time. There are no fancy shields or clever tricks that could possibly ease the way. There is no loophole for adventure, unless you consider entering the afterlife an adventure. By definition, a black hole disassembles anything caught in its web and reduces it to component parts so small they cannot be observed by even the most exacting microscope. Because of the event horizon, black holes cannot be directly observed and no information can emerge from inside. Like a reclusive rock star, you can only spot a black hole by the disaster scene it creates in the neighborhood. Typical effects include a giant spiralling swirl of matter falling into the singularity. As the matter is pulverized (but before it falls into the event horizon), it emits X-rays, highly energetic radiation that moves fast enough to escape the black hole's gravity.

Black holes can also create strange effects in their immediate vicinity. Quasars, the brightest objects known to astronomy, are believed to consist of a super-hot vortex of gas and material detritus rapidly spinning around a supermassive black hole. This notion is extremely hypothetical, however, since the closest quasars are billions of light years away from our own galaxy. This distance also suggests that quasars are very old, possibly forming shortly after the Big Bang. There are many theories about exactly what we mean when we say "Big Bang," and none of them are 100 percent certain (or anywhere close). Many of these theories propose that the entire universe began as a singularity—the ultimate black hole—which then exploded/expanded/inflated into our universe for reasons which are entirely unclear.

Naked singularities have been proven mathematically feasible, which is not to say that you're especially likely to pass one while driving home from work. All black holes are singularities, but not all singularities are black holes. A singularity simply refers to the point in a physical process where the equations break down. There are theoretically other non-black hole singularities which can occur in quantum physics, at the very small scales where reality gets weird. One possible singularity was observed recently in the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider in Brookhaven, New York. Whilst scientists were smashing tiny particles together just to see what would happen, a small black-hole-like phenomenon popped up in the middle of a tiny fireball. The fireball was more or less intentional, but the baby black hole was apparently unexpected. Scientists at RHIC hastened to explain that the black hole was not the same kind of black hole as the giant, star-swallowing, life-exterminating variety, and that no one was ever in any danger.

It's quite another proposition to suggest that nothing could possibly go wrong in the game of cosmic dice-rolling that goes on inside a particle accelerator. Quantum physics experiments are by definition unpredictable. And the behavior of a singularity is also unpredictable—again by definition. So they're using one inherently unpredictable phenomenon to create another inherently unpredictable phenomenon, then predicting that nothing could possibly wrong. It doesn't take a doctorate in nuclear physics to spot the hole in this argument. If you wake up one morning, and half the planet seems to have been sucked into a state of mathematical nonexistence, you won't even have the admittedly petty satisfaction of calling the folks over at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider to see their sheepish grins. They'll be on the other side of the event horizon, from which no information can escape. Bastards.

The Other SingularityIn addition to its traditional scientific use, the word "Singularity" with a capital S has been applied to the only somewhat flaky notion that humanity is rapidly approaching a major event which will radically transform pretty much everything as we know it. The Singularity was coined as a specific phrase by mathematicisn/sci-fi writer Vernor Vinge.Vinge basically makes a case that things are getting whacky and we should expect the unexpected, and that some sort of new intelligence is about to emerge on (or in the general vicinity of) Earth. This seems reasonable, but awfully non-specific. Nevertheless, you can find plenty of people who have articulated some variation the same thing with greater or lesser degrees of credibility, including Jack Parsons, Grant Morrison, Terence McKenna, Arthur C. Clarke and Philip K Dick. |

Physicist John Wheeler first used the phrase "black hole" to describe this phenomenon, which warps the very fabric of space and time into strange shapes. A black hole is a singularity so dense that it absorbs virtually everything around it, even light. Even space collapses, and the spacetime distortion creates an "event horizon"—the point of no return.

Physicist John Wheeler first used the phrase "black hole" to describe this phenomenon, which warps the very fabric of space and time into strange shapes. A black hole is a singularity so dense that it absorbs virtually everything around it, even light. Even space collapses, and the spacetime distortion creates an "event horizon"—the point of no return. While some physicists do believe black holes transport matter into another universe, traveling through a black hole is not unlike travelling through a wood chipper. All your parts end up on the other side, but not in their original configuration. And you won't enjoy the trip. Under this theory, the black hole purees all the matter that falls into it and shoots it out in a jet somewhere else in this universe or an entirely different one.

While some physicists do believe black holes transport matter into another universe, traveling through a black hole is not unlike travelling through a wood chipper. All your parts end up on the other side, but not in their original configuration. And you won't enjoy the trip. Under this theory, the black hole purees all the matter that falls into it and shoots it out in a jet somewhere else in this universe or an entirely different one.  By studying these X-rays, scientists have been able use radio telescopes to spot several likely black holes, including a super-massive one in the center of the Milky Way galaxy, which is devouring stars at a phenomenal rate. This phenomenon may be related to the formation of galaxies, as well as their spiral structure.

By studying these X-rays, scientists have been able use radio telescopes to spot several likely black holes, including a super-massive one in the center of the Milky Way galaxy, which is devouring stars at a phenomenal rate. This phenomenon may be related to the formation of galaxies, as well as their spiral structure.  Black holes may come in some exotic flavors, such as the hypothetical "naked singularity," which could theoretically be directly observed from the outside (unlike a black hole singularity, which is hidden by the blackness and the holeness).

Black holes may come in some exotic flavors, such as the hypothetical "naked singularity," which could theoretically be directly observed from the outside (unlike a black hole singularity, which is hidden by the blackness and the holeness).  However, it's pretty easy to say after the fact that the mini-black-hole couldn't have swallowed the entire Earth and ended all human life—because it didn't happen.

However, it's pretty easy to say after the fact that the mini-black-hole couldn't have swallowed the entire Earth and ended all human life—because it didn't happen.