|

The Gunpowder Plot

For reasons entirely unclear to anyone, the anniversary of a failed 17th century coup known as the Gunpowder Plot has now become a national holiday for Brits, who celebrate with bonfires, songs and drunkenness. After about 100 years of intermittent persecution of Catholics, the British monarchy had managed to piss off a fair-sized portion of the population. By 1600, this had pretty much come to a head. Armed rebellions and vicious reprisals followed in repeating sequence, and the ascension of King James I made things worse. James I was a son of a Catholic, and possibly a lapsed Catholic himself, and we all know how bitter they can be. As soon as he took power in 1603, he began beating the crap out of the Catholics and the Puritans. This so incensed the remaining Catholics that they undertook the most ambitious assassination plot in the annals of British history.

Their plot was largely improvised. Plan A, apparently, was to build a tunnel from a nearby house to the Parliament building. Using the tunnel, the conspirators would then plant enough explosives beneath the building to utterly destroy it. The tunnel building was a bust, however, due to flooding and the awkwardness of breaking down the Parliament's underground walls. Plan B was put into effect and Percy just rented a cellar in the basement of the Parliament. Plan B was much simpler, so much so that a reasonable person must wonder why it wasn't Plan A. It's possible that Plan A was apocryphal. On the other hand, this wasn't the most brilliant conspiracy ever. For instance, the plotters apparently couldn't handle the complicated task of filling a cellar with barrels of gunpowder (thus the name "Gunpowder Plot," get it?). The original circle of conspirators had consisted of five people. You'd think that filling a cellar with 36 barrels of gunpowder could reasonably be handled by five people. But you'd be wrong. Catesby drafted nearly a dozen more conspirators into the plot. Meanwhile, the gunpowder sat in the cellar... and sat... and sat... 1605 was ticking away, and still the big coup was lying dormant. The main reason for this was that the Parliament had been out of session when the bomb was first planted. Apparently coincidental snafus had delayed the return of the legislature for days, then weeks, then months. The gunpowder went bad and Fawkes had to go get more.

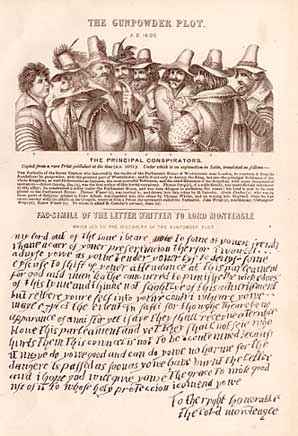

A letter was sent to Lord Monteagle, a Catholic who kept a low profile, warning him not to attend the first day of Parliament. The letter, as preserved by researchers for the Gunpowder Plot Society, read as follows: My lord out of the love i beare to some of youere frends i have a caer of youer preseruacion therfor i would advyse yowe as yowe tender youer lyf to devys some excuse to shift of youer attendance at this parleament for god and man hath concurred to punishe the wickednes of this tyme and think not slightlye of this advertisment but retyre youre self into youre contri wheare yowe may expect the event in safti for thowghe theare be no appearance of anni stir yet i saye they shall receyve a terrible blowe this parleament and yet they shall not seie who hurts them this cowncel is not to be contemned because it may do yowe good and can do yowe no harme for the dangere is passed as soon as yowe have burnt the letter and i hope god will give yowe the grace to mak good use of it to whose holy proteccion i comend yowe.Now, the unsophisticated among you probably look at this letter and think, "These people WERE idiots! They couldn't even spell!" The sophisticates, on the other hand, are wisely nodding to themselves that Middle English was spelled that way. In reality, the truth is somewhere in between. Yes, Middle English was pretty erratic on the basis of both grammar and spelling, but the letter is pretty lame even on that basis. If you spell the same word two different ways in the same sentence (and the whole letter is one big run-on sentence), there's a pretty good chance you're an idiot.

It isn't known which of the conspirators wrote the tipoff letter, but the core group found out about the existence of the letter and mysteriously decided it wasn't any particular cause for concern. The plot went forward as planned. Monteagle notified the authorities, however, and Guy Fawkes was arrested as he finalized the bomb in the cellar, just one day before Parliament was scheduled to begin its session on Nov. 5. Fawkes was tortured until he started spilling names, and the plotters fled London. After briefly gathering a few dozen followers for a major attack, they accidentally set off a bomb while they were trying to build it. Feelings of inadequacy mounted, and they were in fact quite justified. Within a few months, virtually all the conspirators had been rounded up or killed. The survivors were prosecuted for treason early in 1606, most were killed outright, a few rotted in prison. The last to be executed was Guy Fawkes, the man who would forever be tied to the plot and remembered beyond all others. On top of failing as an attack and getting everyone involved executed, the assassination attempt backfired in its political aim, which, as you may be forgiven for having forgotten, was to ease the plight of Catholics in Britain. Instead, the plot aggravated relations between Protestants and Catholics, leading to a whole new series of persecutions.

Regardless of the political savvy of the plotters, you may be wondering why in God's name would the British choose to celebrate this act of terrorism with the drunken shamelessness cited earlier. Every Nov. 5, people drink themselves silly, burn Guy Fawkes in effigy and set off gunpowder fireworks on Guy Fawkes Day. (Which, if you think about it, is particularly ironic since Fawkes was really just the hired muscle.) In overall concept, Guy Fawkes Day is kind of like if Americans spent the next 100 years celebrating Mohammed Atta Day on September 11 by drinking, cheering and blowing up model airplanes with firecrackers. Of course, the September 11 hijackers functioned with deadly efficiency and racked up a body count, while the gunpowder plotters mostly made idiots out of themselves and their attack was foiled. So it can be argued that the British are simply being sore winners, a trait that is found on both sides of the pond. Still, it's more than a little unseemly. And aren't the British supposed to be dignified? Sometimes, when you ponder these questions too long, the world begins to seem like a strange and frightening place. Fortunately, it never takes long for something much worse to come along and drive the first thing out of your mind entirely.

Transcript of Guy Fawkes trial

|

The plotters included Robert Catesby, Thomas Percy, and quite a few others, including the most famous of them (and namesake of the aforementioned holiday),

The plotters included Robert Catesby, Thomas Percy, and quite a few others, including the most famous of them (and namesake of the aforementioned holiday),  A few days before the Parliament finally returned in November, the final stroke of bad luck (or more accurately, the final consequence of bad planning) fell on the unhappy conspirators. Someone ratted them out.

A few days before the Parliament finally returned in November, the final stroke of bad luck (or more accurately, the final consequence of bad planning) fell on the unhappy conspirators. Someone ratted them out. And if you write an anonymous letter to an official of the government to warn him that you are about to attack said government (including where and when you're attacking), you're probably a pretty big idiot.

And if you write an anonymous letter to an official of the government to warn him that you are about to attack said government (including where and when you're attacking), you're probably a pretty big idiot.  In this delusion, Fawkes and Co. were not unlike

In this delusion, Fawkes and Co. were not unlike