|

Embalming On a practical basis, a simple hole in the ground is more than enough mechanism to process a dead body. But even that's a bit extravagant. It's more ecologically efficient to let carrion birds pick clean your bones.

On a practical basis, a simple hole in the ground is more than enough mechanism to process a dead body. But even that's a bit extravagant. It's more ecologically efficient to let carrion birds pick clean your bones. But we're human beings, dammit! We've developed an extensive mythos around death (and its aftermath). Pragmatism just doesn't cut it. Embalming is the art of preserving a dead body, either temporarily or permanently. Once, embalming was considered to be strictly the purview of sober, top-hat-wearing professionals with a morbid streak.

The art of embalming has a rich and vibrant history, but we assume you're more interested in the gory details. So let's start with a quick "do-it-yourself" guide. Keep in mind that you should frequently disinfect surfaces as you work. Wear rubber gloves and an apron. You'll probably want goggles in case you get something wrong. If you're working for a respectable funeral home, you're supposed to wear a respirator. Step One: Find a corpse. You can find corpses just about anywhere people are dying, or you can make your own (not recommended). Step Two: Put the corpse on an embalming table. This is a steel or enameled table with a handy trough around the edges to drain off stray bodily fluids. Step Three: Strip the body naked. You're not supposed to enjoy this, but Big Brother can't regulate your thoughts... yet. Step Four: Make a careful list of jewelry and valuables, which should be removed from the body before the embalming proceeds. If you're a professional mortician, you will use this list to return said valuables to the family. If you're an unprofessional mortician, well, keep in mind that bereaved people have the adrenalin-fueled strength of ten non-bereaved people. Be discreet. Step Five: Shut the mouth of the deceased. Try not to make the corpse look stupid. Step Six: Stretch out the limbs of the dead person. By playing with the arms and legs you will break up the rigor mortis. Have fun with this process, but remember to arrange the limbs in a simple, tasteful way when you're done. Unless you're a jerk, then just do whatever. Step Seven: Pick the flavor of embalming fluid you would like to use. Embalming fluids are basically formaldehyde solutions, but they can be bleached to brighten up that deathlike pallor, or tinted with the ethnically appropriate pantone to give skin that healthy "recently dead" glow.

Step Nine: Add two to four gallons, or until the corpse is full. If the circulatory system is clogged due to clotting or otherwise damaged due to the means of death, repeat the above procedure using other needle points.

Step 11: Stick a long needle into the belly, pump out any fluid within, then pump the body cavities full of embalming fluid. Step 12: Stitch any remaining openings closed, and wash the body with soap and water. Shave any visible facial hair that's not supposed to be there. (Contrary to popular rumor, hair doesn't continue to grow after death, but your skin shrinks, exposing more of the follicle.) Step 13: Dress the corpse. Again, if you're a respectable mortician, keep in mind that you should put pants and underwear on the corpse, even if they're having a half-casket viewing. Apply make-up to the corpse to give it a vaguely lifelike appearance, or at least an "exhibit at the wax museum" appearance. Step 14: Do not under any circumstances perform steps one through 13 unless you're a licensed mortician. What, did you think we're a bunch of barbarians? For God's sake, this is ROTTEN.COM, the last mewling voice of civilization in a world gone mad!

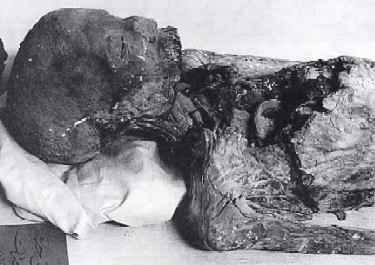

The History of EmbalmingMore than 6,000 years ago, prehistoric residents of South America salted bodies to preserve them in what is probably the earliest example of the science of embalming.The ancient Egyptians advanced the art with an extensive system for pampering the politically important dead—mummification. A form of religiously motivated embalming, mummification required the efforts of several people and took more than a month to complete. Although it was most famously used in Egypt, mummification was also practiced by the Incas, Eskimos and the residents of the Canary Islands.

However, it was the Romans, not the Egyptians, who would determine the course of Western civilization for the next couple of millennia. Unlike the Pharaohs, the Caesars were mostly cremated (but Nero apparently had his wife embalmed). After the downfall of Egyptian society, the practice of embalming rarely surfaced in Western culture to any significant degree. Christians threw their beloved corpses untreated into the ground, and that was that. But the science wasn't quite dead. There were special instances where some form of preservation was desirable. For instance, if a person of means died far away from home, steps would be taken to preserve the corpse until it could be transported to the deceased's family. This was a frequent issue during wartime. Scattered incidents of embalming are reported during the Middle Ages, often among wealthy knights who had suffered misfortune during the Crusades. But the art was stagnant in most meaningful respects from the fall of the Pharaohs until the nearly the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. People tend to blank out the staggering number of casualties inflicted during the American Civil War. More than 600,000 people were killed during the conflict, which is about four times as many soldiers as are stationed in Iraq as of this writing. That's a lot of corpses. Most of the soldiers were just buried where they fell, but officers and the children of privilege were sometimes shipped home for funerals. Packs of opportunistic doctors chased the battling armies of North and South, pouncing on the field after the shooting was done and offering to embalm the corpses for $100 a head so that they could be shipped back home.

In the Civil War, the vast majority of victims had bled to death, so this was simply the path of least resistance. Burr and others like him injected the chemicals through the armpit. Civil War-era embalmers experimented with arsenic, creosote, mercury and even turpentine as their preservatives of choice. But the next great step in the modern mortuary sciences was the invention of formaldehyde in 1868. Formaldehyde was discovered accidentally by Russian chemist Aleksandr Butlerov, and it took a while before anyone thought to start injecting it into dead bodies. Formaldehyde is highly toxic to the living, but is a miracle drug for the dead, hardening tissues and killing off bacteria, mites, maggots and the like. Formaldehyde turns the skin gray, a zombie-like demeanor that is not pleasing to the bereaved, so it's usually combined with bleach or dye before being injected into a corpse. Even with this chemical advancement, normal embalming only preserves a corpse for a few days before nature takes its course. That doesn't mean you can't do better, if you have a mind to. For instance, Lenin was embalmed in a special solution of glycerin, alcohol, water, potassium acetate, quinine chloride, and possibly some secret ingredients. An electric pump was installed inside the body for perpetuity. He gets clean clothes every three years.

Fun Facts About Corpses

|

Today, thanks to progressive cable programming such as Six Feet Under, we know that embalming is the purview of neurotic sex maniacs who are hilariously obsessed with death and habitually demean the dead bodies they process.

Today, thanks to progressive cable programming such as Six Feet Under, we know that embalming is the purview of neurotic sex maniacs who are hilariously obsessed with death and habitually demean the dead bodies they process.

Step Ten: Pour the blood down the drain. Do not

Step Ten: Pour the blood down the drain. Do not  After Alexander the Great destroyed the Egyptian monarchy and its accompanying religion, it occurred to some people that mummification was way, way too much trouble. Mummification went the way of the Pharaohs, but elements of the practice were adopted by other cultures to lesser and greater degrees. (Alexander himself was embalmed in honey and beeswax.) Most Mediterranean cultures practiced some variation on embalming at one time or another, generally gutting the corpse and restuffing it with whatever herbs, oils, resins or other material that made sense for the location.

After Alexander the Great destroyed the Egyptian monarchy and its accompanying religion, it occurred to some people that mummification was way, way too much trouble. Mummification went the way of the Pharaohs, but elements of the practice were adopted by other cultures to lesser and greater degrees. (Alexander himself was embalmed in honey and beeswax.) Most Mediterranean cultures practiced some variation on embalming at one time or another, generally gutting the corpse and restuffing it with whatever herbs, oils, resins or other material that made sense for the location.  Dr. Richard Burr is credited with designing the basic structure of modern embalming practice, the concept of arterial embalming, in which the corpse's veins are filled with a chemical preservative in the place of blood.

Dr. Richard Burr is credited with designing the basic structure of modern embalming practice, the concept of arterial embalming, in which the corpse's veins are filled with a chemical preservative in the place of blood.