|

Professional Wrestling There are a lot of good reasons to refrain from calling professional wrestling "fake."

There are a lot of good reasons to refrain from calling professional wrestling "fake." For one thing, pro wrestlers routinely suffer the sort of grisly and painful injuries one generally associates with the Spanish Inquisition, which is definitely not fake. For another thing, it's highly unlikely that you, the reader, could even once do any of the stunts these guys do 52 weeks a year. And for yet another thing: If you call "pro wrestling" fake within earshot of a wrestler, you will probably get dropped on your head. All that said, pro wrestling is a "work" (one of many colorful and mega-hip "insider" wrestling terms which shall be employed liberally throughout this article). A "work" is a piece of entertainment disguised as a wrestling match, in which the outcome (and usually some elements within the match) have been predetermined by professional writers. There was a time when pro wrestling presented itself as "sports" rather than "sports entertainment." Wrestling as a spectator sport dates back to the homoerotic display of naked Spartans rolling around on the ground together in ancient times. Feats of strength and homoeroticism have a timeless quality, as the movies of Charlton Heston attest. As late as the 19th Century, wrestling was a respected and even prestigious sport, a favorite among every strata of society, from peasant to President (Abraham Lincoln was an accomplished wrestler; interestingly, so was Donald Rumsfeld). But around this time, a divergence occured. In addition to the localized competition of wrestling, traveling carnivals and sideshows began to deliver wrestling exhibitions as an attraction.

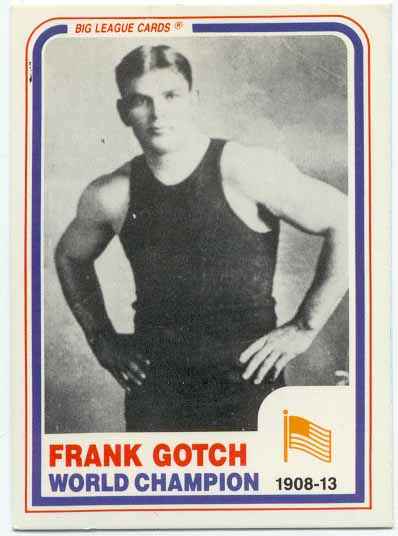

At the same time that wrestling's entertainment factor was being elevated in these shows, disreputable behavior among legitimate athletes in wrestling was tarnishing the image of the real deal. In the early 20th Century, rumors of fixed matches and underhanded tactics began to make pro wrestling look seamy; these were exacerbated when the sterling reputation of pro wrestling's first major champion Frank Gotch was sullied by charges that he organized an attack on one of his opponents before a big match, among various other shenanigans, in order to protect his title. After Gotch, wrestling went into hibernation as a national pasttime, although it still filled arenas in local shows, with matches that could last for hours. Many of these matches were "shoots," the opposite of a "work," in which two guys legitimately duke it out until one wins.

The WorksBut some of them were works; promoters and wrestlers quietly began negotiating fixes. Fans got bored when the top athletes dominated an arena so thoroughly that they became untouchable. The first works were designed to add drama to the process with shocking upset victories or crushing defeats. Championship title belts became bargaining chips to be shuffled around based on what everyone felt was best for the business.Since air travel was not widespread, wrestling promotions were necessarily local in nature. Athletes in various areas of the country competed against each other, and promoters carved out empires for themselves, pulling strings and arranging competitions designed to keep filling seats. Through the 1940s and 1950s, the promoters began to identify elements that fans liked. Shorter matches were near the top of that list. No one wanted to watch one burly guy hold another burly guy in a half-nelson for 45 minutes. The promoters began to set time limits on matches and barred wrestlers from long static displays.

Not that anyone was going to admit it at the time. The performers and promoters of professional wrestling seemed to split off from normal society into a strange little subculture with a set of strict codes and rules. Chief among these was "kayfabe," an old carny term for fakery which evolved to become the credo of the professional wrestler. Kayfabe meant you never, ever, EVER admitted to ANYONE under ANY circumstances that wrestling was anything less than what it seemed to be in the ring. The principle of kayfabe would endure until the late 1980s, when it became a casuality of in-ring and out-of-ring scandals, various legal entanglements and scathing competition. As wrestling carved out its niche on television (with a few false starts along the way), wrestlers began to emerge as personalities, sometimes becoming stars for reasons almost entirely unrelated to their ability to wrestle per se. With the canvas of television before them, wrestling promoters quickly keyed in on the fact that personalities were driving interest in the show. Over the course of the next several decades, the ability to handle a microphone would become as important as the ability to deliver a bone-crunching suplex, if not more so. Starting in the 1950s, the role of "promos" became paramount to the success of a wrestling operation. Promos are interviews or short speeches in which a wrestler lays out the stakes for a battle and defines his persona, giving the audience reasons to love him or hate him.

One of the first great wrestling personalities and one of the greatest heels of all time was "Gorgeous George" Wagner, whose effeminate, cheating villain character caught fire with audiences in the strongly homophobic 1950s. Gorgeous George represented a strange contradiction that wrestling continues to struggle with in the 21st Century. Wrestling and Homosexuality have existed in an uneasy balance that goes all the way back to those naked Spartans. On the one hand, wrestlers cultivated a machismo-laden image that reacted with predictable violence to intimations of homosexuality on screen. At the same time, some wrestlers and many promoters were secretly gay behind the scenes. And if you're running a business that depends on your ability to sell interest in large, musclebound, half-naked men rolling around on a mat, well, let's just say that your target audience might have some issues. Gorgeous George pranced around the mat in fancy cloths and long, curly blond hair. Think Liberace with muscles. He was accompanied to the ring by strapping young men, rather than curvaceous young women. George was the first heel star of the television era. But many would follow. Wrestling quickly became a television staple. Since the promotions were mostly regional, they provided cheap, easily produced content for local broadcasters, and the televised matches drew major ratings. Among the loose alliance of regional promoters, there were winners and losers.

The WWF One of the winners was Vincent McMahon Senior, who ran the World Wide Wrestling Federation, or the WWWF. In addition to being a savvy promoter with a wide-ranging East Coast territory, the luck of the draw meant that McMahon was well-established in one of the first regions to install a cable television network infrastructure, an advantage that would prove decisive in the years to come, but the senior McMahon wouldn't live to see the result. In 1982, he sold the promotion to his son, Vincent Kennedy McMahon. and he died two years later.

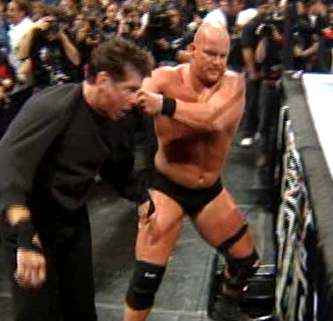

One of the winners was Vincent McMahon Senior, who ran the World Wide Wrestling Federation, or the WWWF. In addition to being a savvy promoter with a wide-ranging East Coast territory, the luck of the draw meant that McMahon was well-established in one of the first regions to install a cable television network infrastructure, an advantage that would prove decisive in the years to come, but the senior McMahon wouldn't live to see the result. In 1982, he sold the promotion to his son, Vincent Kennedy McMahon. and he died two years later.Had he lived, he would likely have been appalled by what was to follow. Vincent K. McMahon was the wrestling promoter to end all wrestling promoters literally. With little direct experience in his father's business and even less cash on hand, McMahon had a vision for what wrestling could be. That vision had everything to do with television. McMahon was the first promoter to see the potential in syndicated television and the eventual emergence of national cable channels. Vince also had a vision for where the money was coming from pay per view, a paradigm which the WWF pretty much invented with the very first Wrestlemania in 1985. McMahon's idea was ahead of its time the technology for PPV barely existed and few homes were wired for cable. Wrestlemania I was broadcast from Madison Square Garden via closed-circuit television to theaters around the country. The WWF quickly became synonymous with wrestling in the United States. McMahon built a stable of superstars who were distinguished by larger-than-life personalities and physiques, beginning with figures like Hulk Hogan, Andre the Giant, Rowdy Roddy Piper and Randy Savage. McMahon scored a major publicity success when pop singer Cindy Lauper inserted herself into a wrestling feud, resulting in a series of MTV cross-promotions and a prime time special, attracting droves of young viewers to what McMahon was beginning to call "sports entertainment" (a polite way of saying "it's fixed").

Vince and the WWF reinvented the format of wrestling for television, adding high-gloss entrance videos and theme music for the wrestlers, recapping past events in short replays, upping production values substantially and attempting (with debateable success) to make the writing more compelling (in a manner extremely similar to daytime soap operas). Although Ted Turner mounted a major challenge to the McMahon dynasty starting in the late 1980s and peaking with a series of ratings triumphs in the late 1990s, the WWF would eventually emerge triumphant. Turner's World Championship Wrestling featured some talent raided from the WWF. including Hulk Hogan and Bret Hart, and created some of its own superstars, such as Goldberg and Booker T. WCW offered a serious threat to the WWF, and the battle got ugly. McMahon was distracted by a major steroid scandal that swept the WWF and at one point threatened to send the promoter himself to prison. McMahon counterprogrammed against WCW with a series of increasingly tasteless and violent segments, which forced him to make on-screen apologies on more than one occasion. An infamous low point included a staged confrontation modeled on "Cape Fear" in which a fake news feed purported to show Stone Cold Steve Austin breaking into another wrestlers' home and terrorizing him and his wife. The victim try to fend Austin off with a gun, and the video feed was ominously "lost." The home viewing audience freaked out; many thought it was real. Gay bashing and misogyny, which had always been present in the world of wrestling, were considered tools for ratings dominance as well. WCW fired back with a variety of tactics, including breaking kayfabe by revealing the endings of WWF's competing matches.

WWF triumphed in the end and bought out WCW in 2001. The last episode of WCW's flagship program, Nitro, featured the McMahon family walking into the arena and taking over the show. The other major national wrestling promotion, Extreme Championship Wrestling, went into bankruptcy around the same, with several stars and the promotion's head writer moving to the WWF. Within months, the WWF was again virtually the only name in U.S. wrestling, and it stayed that way until Vince McMahon met the one opponent he couldn't body slam the World Wildlife Fund, which had inconveniently trademarked the acronym WWF. After years of protracted court battles, the Fund somewhat improbably pinned the Federation, leading McMahon to rename his company WWE in 2002. The newly rechristened WWE and its newest generation of superstars including performers and athletes like Hollywood star The Rock, NCAA and Big 10 champion Brock Lensar, Olympic gold medalist Kurt Angle and Vince-McMahon's soon-to-be-son-in-law Triple H was faced with an open field and virtually no competition, a challenge to which it responded in typical form with a sharp dive in quality, ratings and ticket sales. However, as Vince McMahon continually reminds his nervous investors, wrestling is a cyclical business. And it's likely to come full circle yet again. Just ask the Spartans. See also: Andy Kaufman |

These shows were designed for entertainment, featuring often monstrous men locked in mortal combat... More or less. After all, these guys had to be able to travel from town to town and live with each other in a close-knit community when they weren't in the ring. Allowances were made.

These shows were designed for entertainment, featuring often monstrous men locked in mortal combat... More or less. After all, these guys had to be able to travel from town to town and live with each other in a close-knit community when they weren't in the ring. Allowances were made.  Performance art had entered the building, and there wasn't one tough guy strong enough to throw it out. When television became part of the mix, starting in the late 1950s, it was the last nail in the coffin of professional wrestling as a legitimately competitive sport.

Performance art had entered the building, and there wasn't one tough guy strong enough to throw it out. When television became part of the mix, starting in the late 1950s, it was the last nail in the coffin of professional wrestling as a legitimately competitive sport.  Wrestling had been steadily evolving into a simple morality play which meant that whenever possible, and especially in high-profile main event matches, the formula was to pit a good and pure wrestler (called a "babyface") against a bad and evil wrestler (known as a "heel").

Wrestling had been steadily evolving into a simple morality play which meant that whenever possible, and especially in high-profile main event matches, the formula was to pit a good and pure wrestler (called a "babyface") against a bad and evil wrestler (known as a "heel").  McMahon conducted his personal and professional life in much the same manner as his on-screen persona with lots of high drama, intricate intrigue, unexpected screw jobs and sometimes simply inexplicable behavior.

McMahon conducted his personal and professional life in much the same manner as his on-screen persona with lots of high drama, intricate intrigue, unexpected screw jobs and sometimes simply inexplicable behavior.  In the end, McMahon's best ally in the war against WCW was the management of WCW itself, headed up by Eric Bischoff, which managed to alienate the wrestling talent while spending money exorbitantly. WCW also banked heavily on the marquee value of well-known older wrestlers, who often demanded sky-high payoffs despite being well past their prime as athletes. WWF ratings began the long climb back upward.

In the end, McMahon's best ally in the war against WCW was the management of WCW itself, headed up by Eric Bischoff, which managed to alienate the wrestling talent while spending money exorbitantly. WCW also banked heavily on the marquee value of well-known older wrestlers, who often demanded sky-high payoffs despite being well past their prime as athletes. WWF ratings began the long climb back upward.