|

Mermaids Mermaids are one of the most ancient myths of humanity. Everyone knows the basic template: She's a woman on top but a fish on the bottom. The classic image is that of an alluring, bare-breasted mermaid sitting on a rock, ready to disappear beneath the waves at a moment's notice.

Mermaids are one of the most ancient myths of humanity. Everyone knows the basic template: She's a woman on top but a fish on the bottom. The classic image is that of an alluring, bare-breasted mermaid sitting on a rock, ready to disappear beneath the waves at a moment's notice. First off, let's just make three things perfectly clear. 1) There are no mermaids. 2) There are no mermaids. 3) There are no mermaids. Only two kinds of people seriously claim that mermaids are real: Hoaxers and idiots. We'll come back to this. While they aren't real, mermaids are interesting. Many myths can be traced directly back to one primal source, but the general concept of the mermaid seems to have a universal quality. The earliest and best-known references to mermaids are found in Syrian and Greek myth. The Sirens in the Odyssey are often believed to be mermaids, but that was a later tradition and not part of the original text. Homer didn't describe the sirens as having fishy bits; they were simply sea maidens whose beautiful songs lured men to their deaths. Variations on the theme can be found all over the world—throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa, and even in indigenous American mythology—but there is little common ground among the different iterations, with very few details to be found. This contrasts with legendary beasts like vampires or Yeti, in which very detailed legends have sprung up around specific geographical regions.

Then there are the water nymphs, overtly sexual faery-types who are all woman, but somehow magically connected to water (usually specific bodies of water). These tales are especially common in Asia and Europe, and they usually come across as the least complicated form of male sex fantasy. Actual mermaid stories are fascinating for precisely the opposite reason: they're the most complicated form of male sex fantasy. Mermaids are sex objects on prima facie grounds, but they're missing some salient parts below the waist. And therein lies a tale, so to speak. Coupled with a total lack of non-fraudulent forensic evidence that anything remotely similar to a mermaid has ever existed, the inconsistency of the legends strongly suggests mermaids have a lot more to do with zeitgeist than zoology. That premise gained substantial ground as the Freudian implications of the mermaid became clearer and clearer with each retelling, culminating in the 1836 story of The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen.

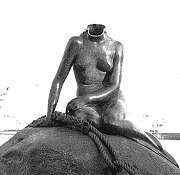

Andersen's mermaid has become a national symbol in Denmark, being depicted in a 1913 bronze sculpture by Edvard Eriksen. The statue is likely most famous for its frequent defacement and dismemberment, occasionally showing up in the news after being beheaded. The first such beheading took place on 24 April 1964; the crime remained a mystery until 1997, when writer Jørgen Nash confessed to severing the head and tossing it into a nearby lake.

Victorian notions of cleanliness aside, the mermaid is a densely layered collection of sexual metaphors and complexes. She's naked and continually wet, with long hair and bare breasts, but she lacks the vagina that (perhaps) dominates the dreams of the sex-starved sailors who encounter her. In The Little Mermaid, she trades her tongue for a vagina, but is forced to endure terrible stabbing pains when she walks, bleeding from her feet, which adds a menstrual motif to an already overcrowded set of symbols.

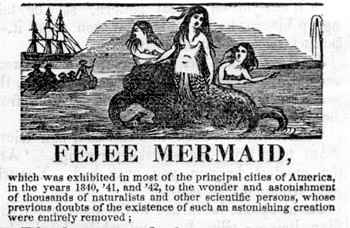

With all this subtext going for it, it's little wonder that the 19th century imagination took the idea of the mermaid and ran with it. People wanted mermaids to be real. The most spectacular manifestation of this trend was the "discovery" of the FeeJee Mermaid by intrepid scientist P.T. Barnum. Unfortunately, in Barnum's hands, the mermaid proved to be the exact opposite of sexy.

With all this subtext going for it, it's little wonder that the 19th century imagination took the idea of the mermaid and ran with it. People wanted mermaids to be real. The most spectacular manifestation of this trend was the "discovery" of the FeeJee Mermaid by intrepid scientist P.T. Barnum. Unfortunately, in Barnum's hands, the mermaid proved to be the exact opposite of sexy. The FeeJee mermaid was supposedly the mortal remains of a genuine mermaid from the "FeeJee" islands in South America. Although Barnum advertised the exhibit with pictures of the traditional bare-breasted beauties, the actual FeeJee mermaid looked like a refugee from a Hollywood pitch gone terribly wrong: "It's like Gremlins meets Piranha meets Ebirah!"

Despite its completely fraudulent origins, the FeeJee mermaid provoked the not-so-hidden desire of the masses to believe in even the most outrageous claims (see Rotten Library entries on Majestic-12, the Bermuda Triangle, the Cottingley Fairies, Numerology, Palmistry, Rabbit's Foot, Fluoridation, Alien Autopsy, Iraqi WMDs, and so on, and so on, and so on).

The FeeJee mermaid inspired numerous imitations which have become valuable, if eccentric, collectors' items. The basic template has exploded into cyberspace recently in the form of e-mail forwards and Web-based hoaxes which pop up sporadically. Any major nautical event, such as the December 2004 tsunami that wiped out hundreds of thousands of lives, can sublimate into yet another batch of e-mails insisting that CNN improbably missed the story of mermaid corpses washing up on every shore.

The persistent nature of the legend has also inspired scientists to take a crack at explaining the worldwide fascination with mermaids. The results of their studies are less than impressive. The best theory they have been able to muster is that the mermaid myth is based on sightings of the dugong, a sea lion species whose females have hooter-like mammary glands.

If the mind-blowingly ugly dugong somehow stimulates your libido and/or awakens your spiritual essence, we suggest you seek help immediately.

|

Often, related cryptozoological creatures are lumped in with your basic mermaid, but many of these belong to unrelated traditions. For instance, there are numerous legends about nautical shapechangers, particularly in Europe and the British Isles, but most of these legends are not mermaid- or even fish-specific. These include Celtic legends of the Silkies (seals) which are more appropriately part of the overall shapechanging framework associated with faery traditions like the Tuatha De Danaan.

Often, related cryptozoological creatures are lumped in with your basic mermaid, but many of these belong to unrelated traditions. For instance, there are numerous legends about nautical shapechangers, particularly in Europe and the British Isles, but most of these legends are not mermaid- or even fish-specific. These include Celtic legends of the Silkies (seals) which are more appropriately part of the overall shapechanging framework associated with faery traditions like the Tuatha De Danaan.  Unlike the

Unlike the  Since the first decapitation, the statue has been subjected to numerous drunken copycat crimes, losing its share of arms and heads over the years, or being dressed in a painted-on crimson bikini top.

Since the first decapitation, the statue has been subjected to numerous drunken copycat crimes, losing its share of arms and heads over the years, or being dressed in a painted-on crimson bikini top.

The FeeJee mermaid was probably modeled after some rare and similarly weird historical artifacts found in Japan. The pedigree of the mummified creature was attested to by one of Barnum's cronies posing as a professor. With the support of several additional letters of scientific authentication (forged by Barnum himself), the FeeJee mermaid became part an insanely popular element of Barnum's traveling show, even after it was exposed as a glued-together conglomeration of parts from several different animals.

The FeeJee mermaid was probably modeled after some rare and similarly weird historical artifacts found in Japan. The pedigree of the mummified creature was attested to by one of Barnum's cronies posing as a professor. With the support of several additional letters of scientific authentication (forged by Barnum himself), the FeeJee mermaid became part an insanely popular element of Barnum's traveling show, even after it was exposed as a glued-together conglomeration of parts from several different animals.  Even after Barnum confessed his fraud in 1855, showings of the FeeJee mermaid still sold out his traveling shows and inspired long lines at his "American Museum." Ironically, today there are now forgeries of the original fraud, and all-new frauds based on forgeries of the original fraud.

Even after Barnum confessed his fraud in 1855, showings of the FeeJee mermaid still sold out his traveling shows and inspired long lines at his "American Museum." Ironically, today there are now forgeries of the original fraud, and all-new frauds based on forgeries of the original fraud.  The frequency of these hoaxes tells you something about the enduring psychology of the myth. Outside the pages of the Weekly World News, you don't see similar hoaxes circulating regarding such mythic creatures as vampires or

The frequency of these hoaxes tells you something about the enduring psychology of the myth. Outside the pages of the Weekly World News, you don't see similar hoaxes circulating regarding such mythic creatures as vampires or  Clearly, these scientists are full of shit. Perhaps they are in denial about the mermaid's resonance with their own subconscious urges. The legend of the mermaid is a weird conglomerate of sexual fantasies, Freudian taboos, innumerable water-based creation myths and perhaps our primal genetic memory of evolving from the sea (after all, fetuses develop something resembling gills during their time in the womb).

Clearly, these scientists are full of shit. Perhaps they are in denial about the mermaid's resonance with their own subconscious urges. The legend of the mermaid is a weird conglomerate of sexual fantasies, Freudian taboos, innumerable water-based creation myths and perhaps our primal genetic memory of evolving from the sea (after all, fetuses develop something resembling gills during their time in the womb).