|

Kid MarketingChildren are like date rapists: they have to be told repeatedly that no means no. Because concepts like parental respect have grown so inexplicably abstract, the average preadolescent continues nagging his parents upwards of nine times for a desired product. Twelve and thirteen year olds—the group most targeted by advertisers -- nag their parents more than fifty times, continuing their unrelenting campaigns of harassment for weeks at a time. Can we have a pool, dad? Can we have a pool, dad? When delivered by a parent, phrases like "no, we will not take you to Mount Splashmore" feel less like big red stop signs and more like invitations for continued debate. In children's marketing circles, this technique is referred to as pester

power, or the Nag

Factor --

not to be confused with the popular pornographic DVD franchise Gag Factor.

The Initiative Media firm acknowledges that fifty percent of

all toy purchases would never have been rung up in a million years had it not

been for the sweet, wailing nags of a child. That's fifty percent across every

conceivable category relating

to children: toy

purchases, trips to fast food restaurants, vacations to amusement parks --

even automotive sales. Car companies offering vehicles with DVD players

aren't selling to mom and dad, they're delivering coded messages of nagging

hope exclusively to the Spongebob set, those who can't last more than five

minutes without audiovisual stimulation. 1. Bare-Necessities Parents. Mom and dad (e.g. Frasier and Lilith Crane) are upscale and affluent, with a two-story house or greater, and at least two cars. One or both has a college degree and graduate work. They are intelligent, and on average more or less resistant to whining. The only successful nag will be the value-added "importance" nag under the guise of a more sophisticated motive. But I need it to finish my science experiment, or: I need to own the complete set of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. 2. Let's Be Pals Parents. (e.g. the mom on Gastineau Girls)

Mom and dad are much younger parents—too young to know what the fuck they're

doing. Typically they'll buy video games and Playstations as much for themselves

as for their children, while everybody wanders around the house wearing Hello

Kitty pajamas and planning a Renaissance fair. Not much hardcore nagging is

required in these families, just add 3. Indulging Parents. (e.g. any parent you've seen on Intervention) Mom and dad are working class parents with very little time or extra spending money. Fast food and toys become transitory substitutes for love, discipline, or home-cooked meals together at the table. Here, nagging sends a message: my child needs something, and buying it will temporarily push away guilt. 4. Conflicted Parents. (e.g. any celebrity parent) Mom and dad have no idea what to buy for their kids, and actually find advertising a resource. At times, they have sneaking suspicions that they really shouldn't take their child to Chuck E. Cheese three times a week, but—eh -- what are you gonna do. It happens, and it makes the nagging go away, at least for awhile.

Eightball cartoonist Daniel Clowes and Black Hole cartoonist

Charles Burns "Children nowadays are tyrants. They contradict their parents, gobble their food, and tyrannize their teachers."—Socrates, 425 B.C. Kid marketing? Sounds like a retarded DJ name. Children aren't burdened with mortgages, rent, groceries or basic utilities—unless mom or dad is makin' them pitch in. They're a highly lucrative market, with a spending power greater than the gross national product of countries like Finland, Portugal and Greece. Teen Research Unlimited is an Illinois mar The number one reason couples remain in love is not that they like the same things—but that they hate the same things. A brand wishing to successfully exploit a long-term relationship with a child must closely align itself with a similar premise. Find out what the kid hates, and then make fun of it. There is nothing more annoying to an avant-garde teen than being told he's on the cutting edge, as he genuinely believes himself to be one hundred percent self-alienated from the social strata.

Calvin Klein claims credit for the most

successful attempt at thumbing its nose at how square and backwards adults

can be. In partnership with Warnaco, Inc., CK launched a billboard

campaign in New York which featured Okay, okay: the nag factor, the billions dollars' worth of anti-market

research, the conspiratorial plots to seize and secure innocent young minds

—we

get it. Big fuckin' deal and who cares. Tell

us something we don't know. Indeed, the most disturbing marketing trend is

what children's companies find themselves battling now: the duh factor.

The segment of our population comprised of pre-adolescents up to and including

age 14 (often referred to mockingly as the tween generation or Millenials) is

rapidly losing their predisposition for creativity and imagination. LEGO, a

company teetering precariously on the premise that kids want to

be creative, has been struggling with exactly that conundrum for just over

a decade. As recently as 1990, the standard box of As a response to this trend, LEGO decreased the number of pieces in each box. Instead of grappling with a full one-hundred pieces to build that Kentucky Fried Chicken or Starbucks Coffee, now you only need ten. And look: these pre-fab green umbrella straws snap directly into the miniature espresso machine—you don't even gotta build 'em. LEGO bricks have gotten bigger, as well: the size of each block in a set has increased steadily over time in direct proportion to your child's inability to manipulate his backwards, clumsy-ass ham hands. Who needs hours of unnecessarily complicated finger work when you're trying to develop your motor skills? Finally, the majority of "bricks" in today's LEGO kits have evolved exactly

as Darwin intended: they're now shaped exactly like the cars, trees, humans,

animals, ships, and The only thing more retarded might be those among us in pursuit of a LEGO Mindstorms hobby. "Challenging" your child to play with electronic, battery-operated toys and program squiggly meta-scripts so his optically sensitive robot greets him at the door with a drink after day care is the easiest thing your child will ever do with his life. Lock him in a room with 10,000 single-cell plastic bricks, and don't let him out until he's successfully constructed the college of his choice. It's inevitable that all these trends in teen marketing continue uninterrupted, because there's no end in the word trend. Except of course at the end of the word trend. |

According

to the Center for Science in

the Public Interest, nagging works best on four specific classes of parents:

According

to the Center for Science in

the Public Interest, nagging works best on four specific classes of parents: your

shit to their shopping list. If mom or dad are employed, pray they can cling

to their tech support jobs.

your

shit to their shopping list. If mom or dad are employed, pray they can cling

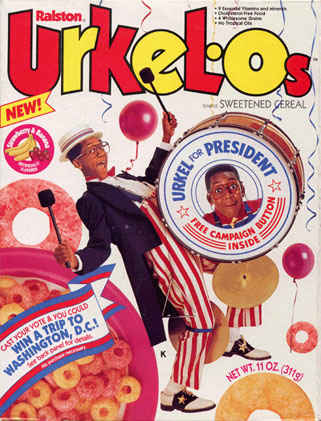

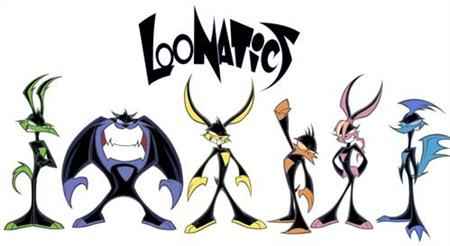

to their tech support jobs.  Cartoon

characters serving as brand mascots provide a quick and easy band-aid to an

otherwise uninspired youth label. Colonel Sanders raps and spits into a drumstick-shaped

microphone about eleven herbs and spizices. Ronald

McDonald pops and breakdances in circles around a freshly-scrubbed

rainbow of multicultural children who sit there lovin'

it. An updated, ostensibly "edgier" Bugs

Bunny turns his baseball cap inside-out. Fat Albert's ringtone wants to know

Where You At. Donald Duck sports ever-blingier ba-bling, and Mickey Mouse

looks more and more like those Tasmanian Devil pimps you see

in cheap tattoo parlors. Even Apple Computer's operating system is branded

with a goddamn smiley face. Kids use icons, SMS shorthand and text messaging

in lieu of more complicated concepts like complete words and sentences sculpted

into structured conversation, and who better to push that agenda then a

Cartoon

characters serving as brand mascots provide a quick and easy band-aid to an

otherwise uninspired youth label. Colonel Sanders raps and spits into a drumstick-shaped

microphone about eleven herbs and spizices. Ronald

McDonald pops and breakdances in circles around a freshly-scrubbed

rainbow of multicultural children who sit there lovin'

it. An updated, ostensibly "edgier" Bugs

Bunny turns his baseball cap inside-out. Fat Albert's ringtone wants to know

Where You At. Donald Duck sports ever-blingier ba-bling, and Mickey Mouse

looks more and more like those Tasmanian Devil pimps you see

in cheap tattoo parlors. Even Apple Computer's operating system is branded

with a goddamn smiley face. Kids use icons, SMS shorthand and text messaging

in lieu of more complicated concepts like complete words and sentences sculpted

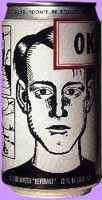

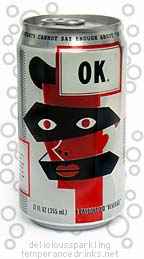

into structured conversation, and who better to push that agenda then a  lightly tiptoed into teen marketing on a global scale when they

designed artwork for a line of Coca-Cola drinks. Named after the most

recognized word in any language—the second being "Coke"—

OK Soda was a short-lived brand keenly aimed at what passed for

the "Generation X" demographic in early 1994. The brand was one of

the earlie

lightly tiptoed into teen marketing on a global scale when they

designed artwork for a line of Coca-Cola drinks. Named after the most

recognized word in any language—the second being "Coke"—

OK Soda was a short-lived brand keenly aimed at what passed for

the "Generation X" demographic in early 1994. The brand was one of

the earlie st to capitalize on the idea that young people were—what's the

word? Disillusioned? Disenfranchised. Disaffected? How about disinterested. The

labels were great, the soda was terrible, and less than a year later the cans

were yanked from shelves. To this day, The OK Soda legacy remains one of the

most transparent, desperate and ridiculous youth campaigns ever made by

st to capitalize on the idea that young people were—what's the

word? Disillusioned? Disenfranchised. Disaffected? How about disinterested. The

labels were great, the soda was terrible, and less than a year later the cans

were yanked from shelves. To this day, The OK Soda legacy remains one of the

most transparent, desperate and ridiculous youth campaigns ever made by  keting think tank which has

interviewed over a million teenagers. They've conservatively estimated

that teens in 2006 would spend upwards of $159 billion of their own money and

their parents' money combined. Teens need jobs, but as a result of our upside-down

economy, adult workers around the country are clinging desperately to all the

decent entry-level service positions. Teenage unemployment is at an all time

high, and rising gas

prices means

that while an unprecedented cache of teen dollars might be temporarily flowing

directly into gas tanks, kids can't drive all the way to and from the

keting think tank which has

interviewed over a million teenagers. They've conservatively estimated

that teens in 2006 would spend upwards of $159 billion of their own money and

their parents' money combined. Teens need jobs, but as a result of our upside-down

economy, adult workers around the country are clinging desperately to all the

decent entry-level service positions. Teenage unemployment is at an all time

high, and rising gas

prices means

that while an unprecedented cache of teen dollars might be temporarily flowing

directly into gas tanks, kids can't drive all the way to and from the  Apple

store as often as they'd like. Ninety-nine cents for a song? Fuck

that noise, I'll LimeWire it. Christ on the cross, it sucks anyway. Trash can. Weirdly,

today's incoming crop of teens are reportedly devoted to bizarre concepts like

God and

their own

mothers—in that order.

Apple

store as often as they'd like. Ninety-nine cents for a song? Fuck

that noise, I'll LimeWire it. Christ on the cross, it sucks anyway. Trash can. Weirdly,

today's incoming crop of teens are reportedly devoted to bizarre concepts like

God and

their own

mothers—in that order. When

a clothing company like Diesel embeds

anti-advertising messages directly in its print and billboard campaigns, it

represents a hackneyed paradoxical chestnut which young people

haven't already seen a million times. When Benetton offers yearly

catalogs "united in color" featuring cocky, self-confident bumper sticker platitudes

about sex, religion, and racism alongside images of death-row inmates or handicapped

children, kids don't immediately recognize that their clothing manufacturer

is boldly "coming forward" in favor of something nobody ever needs to formulate

an opinion about. The screaming scraps of press generated from these early

examples of extreme-to-the-max slabs of kiddie content—especially when a

community of uptight parents

When

a clothing company like Diesel embeds

anti-advertising messages directly in its print and billboard campaigns, it

represents a hackneyed paradoxical chestnut which young people

haven't already seen a million times. When Benetton offers yearly

catalogs "united in color" featuring cocky, self-confident bumper sticker platitudes

about sex, religion, and racism alongside images of death-row inmates or handicapped

children, kids don't immediately recognize that their clothing manufacturer

is boldly "coming forward" in favor of something nobody ever needs to formulate

an opinion about. The screaming scraps of press generated from these early

examples of extreme-to-the-max slabs of kiddie content—especially when a

community of uptight parents  semi-naked toddlers posing in tight

underwear. Public outcry resulted in then-mayor Rudy Guiliani yanking the ads

straight down—a real triumph in "numerically

measurable mainstream accessibility," to quote Channel 101 co-founder

Dan Harmon. It's unclear how many toddlers who saw the CK ad were subsequently

inspired to tart themselves up a little more.

semi-naked toddlers posing in tight

underwear. Public outcry resulted in then-mayor Rudy Guiliani yanking the ads

straight down—a real triumph in "numerically

measurable mainstream accessibility," to quote Channel 101 co-founder

Dan Harmon. It's unclear how many toddlers who saw the CK ad were subsequently

inspired to tart themselves up a little more.  LEGO

bricks contained anywhere from 500 to 1000 pieces. Through sales research,

focus groups and peer review, LEGO now believes such a set is way, way too

complex. Let's dial it back a bit: not only do children

not have the patience to gather together all the required parts for

a castle, or boat, or car—there isn't enough space in their tiny,

ridiculous brains to previsualize long-term plans, imagine new forms, or create

the requisite custom shapes.

LEGO

bricks contained anywhere from 500 to 1000 pieces. Through sales research,

focus groups and peer review, LEGO now believes such a set is way, way too

complex. Let's dial it back a bit: not only do children

not have the patience to gather together all the required parts for

a castle, or boat, or car—there isn't enough space in their tiny,

ridiculous brains to previsualize long-term plans, imagine new forms, or create

the requisite custom shapes. rockets

originally subject to interpretation by a kid's imagination. And which set

of LEGO is right for you? Choose from styles like

Harry Potter, Star Wars, Exoforce, Knight's Kingdom, Bionicle, and numerous

other brandy-brands too depressing even to think about. It's only a matter

of time before LEGO starts packaging their product directly inside the Happy

Meal carton.

rockets

originally subject to interpretation by a kid's imagination. And which set

of LEGO is right for you? Choose from styles like

Harry Potter, Star Wars, Exoforce, Knight's Kingdom, Bionicle, and numerous

other brandy-brands too depressing even to think about. It's only a matter

of time before LEGO starts packaging their product directly inside the Happy

Meal carton.