|

William Marston As the inventor of the lie detector, William Marston wielded massive influence over the development of American society, but that was nothing compared to the impact he made when he created the comic book character of Wonder Woman.

As the inventor of the lie detector, William Marston wielded massive influence over the development of American society, but that was nothing compared to the impact he made when he created the comic book character of Wonder Woman. If he was writing comic books today, Marston would be eaten alive by the morality police. A college professor, Marston was fascinated by sexual bondage and lived openly in a menage-a-trois with his wife and a young student. As a graduate student at Harvard around the turn of the 20th century, Marston helped develop the principles which would eventually form the basis for the polygraph machine. Marston found correspondences between lying and blood pressure. In 1915, he built a device to measure changes in blood pressure and equate them to truthfulness, with the assistance of sophisticated questioning techniques. Marston's research quickly caught the eye of the federal government, including the FBI and the Department of War, which wanted to use his techniques to question prisoners during World War I. Marston was called in to consult on the Lindbergh Baby kidnapping case, but his contribution was rejected by the judge.

Marston's sexual ethics were based on a theory of gender characteristics that classed men as aggressive and conflict-oriented, and woman as "alluring" and submissive. Marston claimed that his vision of women's submissiveness was actually empowering. Although many guys who like dominating women are prone to such claims, Marston made an effort to expand and explain his vision through his literary output. Marston's first effort was the 1932 novel Venus With Us, a sexcapade starring Julius Caesar and many, many women. Marston cranked out a few more popular books (in addition to his prodigious academic output), but nothing clicked.

During a conversation with an editor at D.C., Marston pitched his idea for a female superhero who would provide a role model for girls, displaying what he believed to be the most powerful feminine qualities—sexual allure and "domination via submission," in which women made themselves so irresistible to men that men would willingly allow women to rule them. Or that men would sublimate their aggressive impulses by submitting to erotic bondage, which would then empower women. Or that women could be physically strong but still sexy, and that their strength wasn't compromised if they got tied to beds by supervillains on a regular basis. Or something like that. The overarching point was that bondage was good, and that society would be well-served by inculcating prepubescent boys and girls with images of bondage. As Marston himself attempted to explain it:

Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, and power. Not wanting to be girls, they don't want to be tender, submissive, peace-loving as good women are. Women's strong qualities have become despised because of their weakness. The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with the strength of Superman plus all of the allure of a good and beautiful woman.

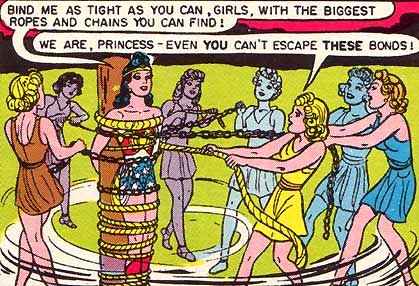

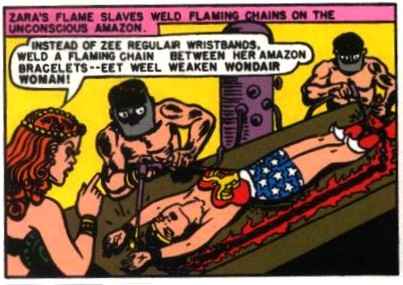

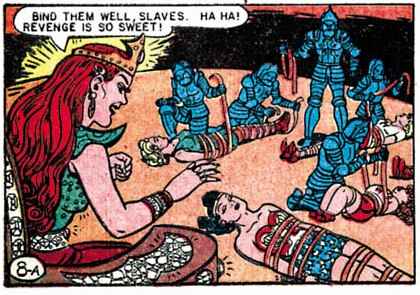

Her costume consisted of a bustier, a tiny skirt, manacles on her wrists and a pair of red, knee-high boots with spiked heels, all in the colors and patterns of the American flag to boot. Wonder Woman also carried a golden lasso for binding her opponents and making them submit to her loving allure. Week after week, Marston placed Wonder Woman into peril and bondage, even featuring several bondage scenes within a single story when he got carried away. Wonder Woman frequently found herself tied to beds, or bound by the wrists with her ass in the air, but sometimes she got to play the dominatrix as well, tying up men and women individually or in groups. Marston's editors were vaguely suspicious—wink wink, nudge nudge—that there might be a sexual subtext to all this imagery.

Marston wrote Wonder Woman until his death in 1947, reaping significant profits for himself and his heirs thanks to a savvy contract (unlike those signed by the creators of Batman and Superman, which left said creators virtually destitute while D.C. reaped billions in revenue over the course of decades).

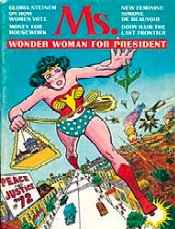

Wonder Woman has been a mainstay of DC Comics since her debut, but her popularity waned once she was separated from her B&D roots. She enjoyed a brief resurgence in the 1970s, first as a feminist icon and subsequently as a bimbo-esque TV action star, but she never regained the power she wielded as a 1940s-era submissive, alluring free-spirit sex kitten. So was Marston an altruistic genius conducting a radical experiment in social engineering, or just a dirty old man getting his rocks off? History has not yet rendered its judgment, and neither will the Rotten Library. We will simply note that the first generation of Wonder Woman readers entered young adulthood in the 1960s—a decade Marston would have loved had he lived to see it. There may be hope yet for the Amazon princess. In 2005, Joss Whedon—creator of Buffy the Vampire Slayer—announced he would write and direct a new Wonder Woman movie. Based on his previous work, Whedon probably has a better-than-average chance to recreate Marston's kinky-yet-empowering worldview. And he's less smug than Quentin Tarantino. |

Although his invention was quickly surpassed by more sophisticated devices, Marston remained a fervent advocate of the technology. He settled into a career as a psychologist and teacher. Marston married in 1915, then in 1920, he met an attractive young student, who moved in with the couple as husband and wife and wife (but without a formal marriage contract).

Although his invention was quickly surpassed by more sophisticated devices, Marston remained a fervent advocate of the technology. He settled into a career as a psychologist and teacher. Marston married in 1915, then in 1920, he met an attractive young student, who moved in with the couple as husband and wife and wife (but without a formal marriage contract).  He had more success as an adviser to the literate and famous, acting as a consultant to Hollywood studios and later to D.C. Comics, home of such American icons as Sargon the Sorcerer, Dr. Occult, Slam Bradley and the Star-Spangled Kid (with Stripesy), as well as a cast of second-stringers that included some guys named

He had more success as an adviser to the literate and famous, acting as a consultant to Hollywood studios and later to D.C. Comics, home of such American icons as Sargon the Sorcerer, Dr. Occult, Slam Bradley and the Star-Spangled Kid (with Stripesy), as well as a cast of second-stringers that included some guys named  With these philosophical underpinnings, Wonder Woman debuted in 1941 as a bizarre mix of progressive feminism and hot bondage action. Wonder Woman's superpowers were roughly equivalent to those of Superman, who had debuted a couple years earlier. (In the those days, Superman was somewhat less omnipotent than his later incarnations.)

With these philosophical underpinnings, Wonder Woman debuted in 1941 as a bizarre mix of progressive feminism and hot bondage action. Wonder Woman's superpowers were roughly equivalent to those of Superman, who had debuted a couple years earlier. (In the those days, Superman was somewhat less omnipotent than his later incarnations.)  If they had bothered to read Marston's academic writings, his editors might have been more suspicious. If they had happened to read his high-profile interviews with national magazines in which he enthusiastically boasted that he was subliminally implanting bondage imagery in the minds of American youth, well, they might have been even more suspicious. But Wonder Woman had become one of D.C.'s best-selling comic books, so the editors were content to let these issues fall by the wayside.

If they had bothered to read Marston's academic writings, his editors might have been more suspicious. If they had happened to read his high-profile interviews with national magazines in which he enthusiastically boasted that he was subliminally implanting bondage imagery in the minds of American youth, well, they might have been even more suspicious. But Wonder Woman had become one of D.C.'s best-selling comic books, so the editors were content to let these issues fall by the wayside.  Interestingly, Marston's fetishes didn't become an issue during the virulent anti-comics backlash of the 1950s. Although comics were demonized for corrupting the morals of children, the main complaints leveled against Wonder Woman had more to do with her uppity feminism than her B&D overtones.

Interestingly, Marston's fetishes didn't become an issue during the virulent anti-comics backlash of the 1950s. Although comics were demonized for corrupting the morals of children, the main complaints leveled against Wonder Woman had more to do with her uppity feminism than her B&D overtones.