Richard Scarry

"I'm

not interested in creating a book that is read once and then placed on

the shelf and forgotten. I am very happy when people have worn out my

books, or that they're held together by Scotch tape." "I'm

not interested in creating a book that is read once and then placed on

the shelf and forgotten. I am very happy when people have worn out my

books, or that they're held together by Scotch tape."

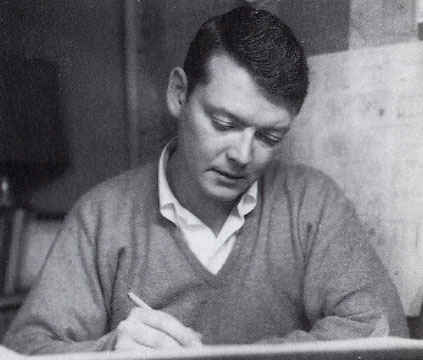

Richard McClure Scarry (1919—1994) revealed to children the

secrets of everyday life. His worlds were easily understood, populated

by polite, well-mannered animals with a keen eye

for absurd human behavior. Scarry himself bumbled his way through a charmed

life of good luck and fortunate circumstance, pretty much doing whatever

he liked until the day he died.

First editions of his 19-cent books presently fetch hundreds of dollars.

He wrote and illustrated over three hundred major picture books for children,

each one dense with slapstick and visual humor. More than three hundred

million copies of his work have exchanged hands, some of which were translated

into thirty languages. This qualifies him to be the most popular children's

book author of all time, and it can be argued there are two types of people:

those who grew up reading Richard Scarry, and those who remain perpetually

maladjusted to society.

R ichard

Scarry hated school, and he never paid attention in class. He'd find slithering

garter snakes in the grassy courtyard and set them wriggling on smooth

tabletops at the library. He delighted in the terrified screams of little

girls. The head librarian screamed once or twice too often, and finally

she banished him from the library forever. That was the beginning of the

end for Richard, and his on again / off again love affair with traditional

education. A fitting irony, it can be acknowledged, that years later the

children's section of the Boston Public Library would be permanently stacked

full of his work, and extremely popular with troublemakers of equal or

greater attention deficit disorder. ichard

Scarry hated school, and he never paid attention in class. He'd find slithering

garter snakes in the grassy courtyard and set them wriggling on smooth

tabletops at the library. He delighted in the terrified screams of little

girls. The head librarian screamed once or twice too often, and finally

she banished him from the library forever. That was the beginning of the

end for Richard, and his on again / off again love affair with traditional

education. A fitting irony, it can be acknowledged, that years later the

children's section of the Boston Public Library would be permanently stacked

full of his work, and extremely popular with troublemakers of equal or

greater attention deficit disorder.

The

young master Dick received D's and F's on homework assignments with such

regularity that his poor performance nearly caused him to drop out of

junior high. When he finally reached the upper grades, he often skipped

school to attend burlesque shows in downtown Boston's Scollay Square. The

young master Dick received D's and F's on homework assignments with such

regularity that his poor performance nearly caused him to drop out of

junior high. When he finally reached the upper grades, he often skipped

school to attend burlesque shows in downtown Boston's Scollay Square.

Scarry discovered the mysteries of sex at a very early age. Perhaps too

early. To him, any girl who took off her clothes while slinking about

the stage was worthy of intense scrutiny. More so than Algebra, anyway,

which he was forced to repeat twice b efore

passing. During these mind-numbing extended math sessions, he practiced

copying his mother's handwriting in order to forge notes from home. Dear

Miss O'Conner, one note read. Richard couldn't attend school yesterday.

He had a bad cough. Signed, Mrs. Scarry. After his frequent absences

were finally tallied up, it took him five years to complete high school. efore

passing. During these mind-numbing extended math sessions, he practiced

copying his mother's handwriting in order to forge notes from home. Dear

Miss O'Conner, one note read. Richard couldn't attend school yesterday.

He had a bad cough. Signed, Mrs. Scarry. After his frequent absences

were finally tallied up, it took him five years to complete high school.

He

drew countless pictures of one girl in particular (during his "alone

time") and inevitably these crude, charcoal nudie pics were discovered

by his parents. His father, a serious and conservative businessman, was

convinced his son's obsession with women, artwork, and ditching school

would lead to a sad, pathetic life in a attic, with nothing but canned

spaghetti for breakfast. One evening he seized one of Richard's early

illustrations—a half-naked girl swinging tassels from her nipples—

and confronted the boy directly: "What's going to become of you,

Richard?" He

drew countless pictures of one girl in particular (during his "alone

time") and inevitably these crude, charcoal nudie pics were discovered

by his parents. His father, a serious and conservative businessman, was

convinced his son's obsession with women, artwork, and ditching school

would lead to a sad, pathetic life in a attic, with nothing but canned

spaghetti for breakfast. One evening he seized one of Richard's early

illustrations—a half-naked girl swinging tassels from her nipples—

and confronted the boy directly: "What's going to become of you,

Richard?"

"If

I'm going to be an artist, sir, I have to learn how to draw the human

form," came the reply. "If

I'm going to be an artist, sir, I have to learn how to draw the human

form," came the reply.

Possibly Richard needed a real father figure. Some kind of male influence

who could help him win as many girls as possible. He listened intently

to his Uncle Arthur, a white-haired, sun-tanned ladies' man kinda-guy

who lived in New York. Arthur told truly tall tales about the many women

who swooned for him, and Richard took to heart one piece of his uncle's

wisdom: "Buy a natural linen suit at Brooks Brothers, with a pale

blue shirt to wear under it. This is the only thing you need to learn

in life."

Richard

purchased just such a suit, and paid for it by putting in long hours selling

neckties at his father's department store. Unfortunately, it failed to

impress the admissions officer at Harvard University, where his father

was hoping he'd enroll and eventually get accepted. Double-unfortunately,

Richard's grades had been terrible from the very start, and certainly

not ivy league material, to say the least. Richard

purchased just such a suit, and paid for it by putting in long hours selling

neckties at his father's department store. Unfortunately, it failed to

impress the admissions officer at Harvard University, where his father

was hoping he'd enroll and eventually get accepted. Double-unfortunately,

Richard's grades had been terrible from the very start, and certainly

not ivy league material, to say the least.

At

his father's request, Richard attended a local business college, but his

agonizing, indelible hatred for school compelled him to drop out before

the end of his first year. Eventually, his father gave up. He abandoned

any pretext of having control over Richard's mind, and shipped him off

to art school at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts. And wouldn't you know it,

Richard flourished in the welcoming atmosphere of nude models, drawing

pencils, and paint. It was supposed to be a new start for the young man

—but World War II broke out, ending his art studies permanently. One

year shy of graduation, Richard was drafted into the army. He would never

receive his diploma. At

his father's request, Richard attended a local business college, but his

agonizing, indelible hatred for school compelled him to drop out before

the end of his first year. Eventually, his father gave up. He abandoned

any pretext of having control over Richard's mind, and shipped him off

to art school at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts. And wouldn't you know it,

Richard flourished in the welcoming atmosphere of nude models, drawing

pencils, and paint. It was supposed to be a new start for the young man

—but World War II broke out, ending his art studies permanently. One

year shy of graduation, Richard was drafted into the army. He would never

receive his diploma.

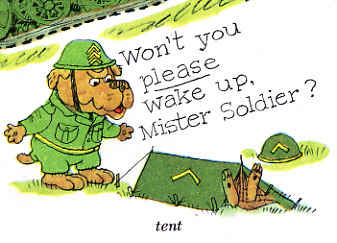

O n

his first day of service, the army told him to list his occupations on

a questionnaire. When Richard scribbled the word ARTIST, he was

shipped off to radio repair school in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Goddamnit!

More fucking school! Jesus Christ! He failed the exam miserably, of course,

earning the unheard-of lowest score in the history of the class: minus

thirteen. The barracks were enormous and dismal, the lessons in proper

bedmaking ridiculous. His drill sergeant was loathsome. Learning how to

walk again, left—right—left—right. Richard had no idea how

his life had come to this. n

his first day of service, the army told him to list his occupations on

a questionnaire. When Richard scribbled the word ARTIST, he was

shipped off to radio repair school in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Goddamnit!

More fucking school! Jesus Christ! He failed the exam miserably, of course,

earning the unheard-of lowest score in the history of the class: minus

thirteen. The barracks were enormous and dismal, the lessons in proper

bedmaking ridiculous. His drill sergeant was loathsome. Learning how to

walk again, left—right—left—right. Richard had no idea how

his life had come to this.

In no time at all, he was ordered to report to the major's office. Wondering

what he'd done wrong, Richard tried delivering a smart and snappy salute,

but he was so nervous  his

hand trembled. his

hand trembled.

"I see you're an artist, Scarry," said the major. "Can

you paint letters? A, B, C—that sort of thing?"

"Yes, indeed, sir," Private Scarry answered.

And so. Richard was assigned two sloppy buckets of paint, silver and

black, both thicker than tar. He flung the paints from their buckets and

spread them with a broom. He was ordered to paint a sign nearly thirty

feet long: WELCOME TO THE SEVENTH ENGINEERS OF FORT MONMOUTH, NEW JERSEY.

It was a task which could easily keep him busy for the entire war, but

after a few weeks the paint had dried. Dick's talents as an artist were

finally being recognized! By the United States military, no less!

After

that, everything changed for Richard. While his less fortunate army buddies

were running laps with heavy backpacks in the hot sun, Richard g After

that, everything changed for Richard. While his less fortunate army buddies

were running laps with heavy backpacks in the hot sun, Richard g ot

weekly passes to take a bus to New York, where he'd dance with young women

at the U.S.O. Assigned to Special Services, Scarry relocated to Lee University

in Lexington, Virginia, a beautiful campus with p-l-l-lenty

of innocent, excitable girls in perpetual attendance from the nearby Red

Cross and the Nurses Corps. Not only that, he received a medical discharge

excusing him for from any strenuous physical activity. No forgery required

this time, it was like getting a ninety day vacation for free. ot

weekly passes to take a bus to New York, where he'd dance with young women

at the U.S.O. Assigned to Special Services, Scarry relocated to Lee University

in Lexington, Virginia, a beautiful campus with p-l-l-lenty

of innocent, excitable girls in perpetual attendance from the nearby Red

Cross and the Nurses Corps. Not only that, he received a medical discharge

excusing him for from any strenuous physical activity. No forgery required

this time, it was like getting a ninety day vacation for free.

Shortly thereafter, he was assigned the daunting task of being the military's

"art director".  A

colonel from headquarters had informed him that his new job was to tell

the troops why they were fighting, and send them news from home.

Richard had no idea how he was meant to accomplish such a task. When he

asked the colonel how, the colonel shouted, "By post!" and slammed

the door behind him. A

colonel from headquarters had informed him that his new job was to tell

the troops why they were fighting, and send them news from home.

Richard had no idea how he was meant to accomplish such a task. When he

asked the colonel how, the colonel shouted, "By post!" and slammed

the door behind him.

How

could an inexperienced young soldier like Richard Scarry possibly bolster

the morale of the entire American fighting force stationed around the

world? By plagiarizing Time magazine, of course. He had copies

flown in; he paraphrased the important parts, created some illustrations,

and turned it into a flier duplicated by mimeograph. It was the best assignment

he'd ever had, and soon he was editor and writer of Publications for the

Information and Morale Services Section of the Allied Force Headquarters.

This job gave him even more leisure time, enabling him to travel

around the world How

could an inexperienced young soldier like Richard Scarry possibly bolster

the morale of the entire American fighting force stationed around the

world? By plagiarizing Time magazine, of course. He had copies

flown in; he paraphrased the important parts, created some illustrations,

and turned it into a flier duplicated by mimeograph. It was the best assignment

he'd ever had, and soon he was editor and writer of Publications for the

Information and Morale Services Section of the Allied Force Headquarters.

This job gave him even more leisure time, enabling him to travel

around the world  to Africa, Algiers, Italy, and France. He took long walks, sat in cafes,

studied ancient ruins, visited art museums and churches. The experience

instilled in him a great love of travel and foreign culture which would

later be reflected in his best-selling children's book Busy Busy World.

to Africa, Algiers, Italy, and France. He took long walks, sat in cafes,

studied ancient ruins, visited art museums and churches. The experience

instilled in him a great love of travel and foreign culture which would

later be reflected in his best-selling children's book Busy Busy World.

Scarry would later declare to his colleagues that World War II was—

in his opinion—the "best war ever".

When Japan surrendered on August 14, 1945, World War II came to an end.

Richard was now a 27 year-old civilian who could honestly report he'd

had experience developing entertaining content for an audience of more

than one million readers each week. He looked forward to getting a "real"

job, and he was hired to work in the art department of Vogue magazine,

a Condé Nast publication. Hooray!!

Three

weeks later, he was fired. D'oh.

No reason was given, apart from the fact that Richard "just wasn't

right for the position." When he asked why they'd bothered to hire

him in the first place, the personnel officer said—no joke—that she'd

been impressed by his white linen suit and blue shirt. Three

weeks later, he was fired. D'oh.

No reason was given, apart from the fact that Richard "just wasn't

right for the position." When he asked why they'd bothered to hire

him in the first place, the personnel officer said—no joke—that she'd

been impressed by his white linen suit and blue shirt.

He found a small apartment in Manhattan's East Side, for which he paid

—again, no joke—fourteen dollars a month. During the mid 1940s, a person

could live on $1000 a year—and Richard lived well, despite being a child

of the Depression years. He secured a job in an advertising agency pasting

up photographs for layouts, but the work was uncreative and boring. He

lasted three months, eventually devoting himself to free-lance illustration.

He maintained an active social life, going to parties, good restaurants

and chasing after attractive young women. When Holiday magazine paid him

$2000 for a single assignment, he relocated to an even better bachelor

pad in Washington Square, where the  cocktail

parties were nearly a hundred times more elaborate. It was in this neighborhood

that he met a particularly charming young lass by the name of Patsy Murphy,

who would later become his one and only wife. His days of womanizing were

over, and he proposed to her efficiently, by telegram: cocktail

parties were nearly a hundred times more elaborate. It was in this neighborhood

that he met a particularly charming young lass by the name of Patsy Murphy,

who would later become his one and only wife. His days of womanizing were

over, and he proposed to her efficiently, by telegram:

MUST MOVE GRAND PIANO.

HEAVY. NEED HELP. COME IMMEDIATELY. ...DICK

If you can call that a proposal. Patsy and Richard were married September

11, 1948, and so intent was he on becoming a competent artist that his

personality began to change. He grew quiet and withdrawn, and he wasn't

much of a talker. Meanwhile, Patsy was outgoing, a drinker, a smoker—

very extroverted and gregarious. She loved entertaining, she loved people

and parties. It was a perfect arrangement; Patsy guided him through tedious

social engagements, often acting as a buffer between him and his publisher.

Scarry was turning into a disciplined worker, rising shortly before eight

each morning, and drawing in his studio until four in the afternoon. An

hour break for lunch. Patsy wasn't allowed to talk to him during this

time; she simply set a ham sandwich and pickles on his desk and went back

downstairs.

That

summer, he got his first big break. The Artists and Writers Guild, a small

editorial subsidiary in New York financed by the Western Printing Company

was producing mass-market activity books and games. One of their creations

were Little Golden Books, which sold for twenty-five cents each. After

Scarry submitted his portfolio—which at that time consisted mostly of

cartoonish human characters—they signed him to a one-year exclusive

services contract worth an astonishing $4800. That

summer, he got his first big break. The Artists and Writers Guild, a small

editorial subsidiary in New York financed by the Western Printing Company

was producing mass-market activity books and games. One of their creations

were Little Golden Books, which sold for twenty-five cents each. After

Scarry submitted his portfolio—which at that time consisted mostly of

cartoonish human characters—they signed him to a one-year exclusive

services contract worth an astonishing $4800.

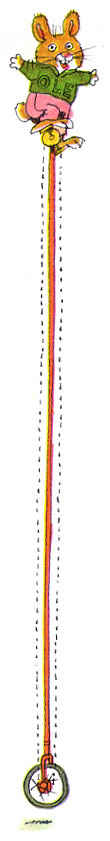

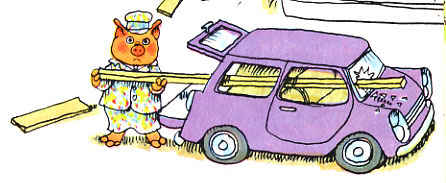

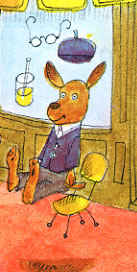

It

wasn't until 1959 that his animal characters emerged as real people. Naughty

Bunny told the story of a little bunny who constantly tracked mud

all over the carpet and kept his room in a state of perpetual disaster,

driving his poor mother to tears. It

wasn't until 1959 that his animal characters emerged as real people. Naughty

Bunny told the story of a little bunny who constantly tracked mud

all over the carpet and kept his room in a state of perpetual disaster,

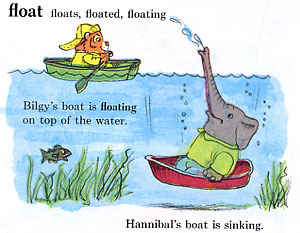

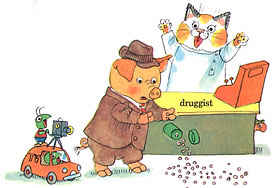

driving his poor mother to tears.  Scarry

wanted to create a different kind of world for children, one with equal

parts humor and pathos. He had a secret plan to develop a new kind of

dictionary which arranged words by categories instead of the alphabet.

This format would allow him to draw over fourteen hundred solo panels

of slapstick anthropomorphic behavior, introduce lots of new characters,

and write short amusing texts for each category. The result was Richard

Scarry's Best Word Book Ever, hardbound at 10.5 x 11.7 inches in oversized

format. It truly dwarfed all others, selling seven million copies in only

a few short years. The Scarry genius had broken loose. Scarry

wanted to create a different kind of world for children, one with equal

parts humor and pathos. He had a secret plan to develop a new kind of

dictionary which arranged words by categories instead of the alphabet.

This format would allow him to draw over fourteen hundred solo panels

of slapstick anthropomorphic behavior, introduce lots of new characters,

and write short amusing texts for each category. The result was Richard

Scarry's Best Word Book Ever, hardbound at 10.5 x 11.7 inches in oversized

format. It truly dwarfed all others, selling seven million copies in only

a few short years. The Scarry genius had broken loose.

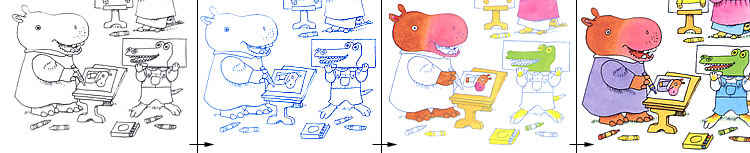

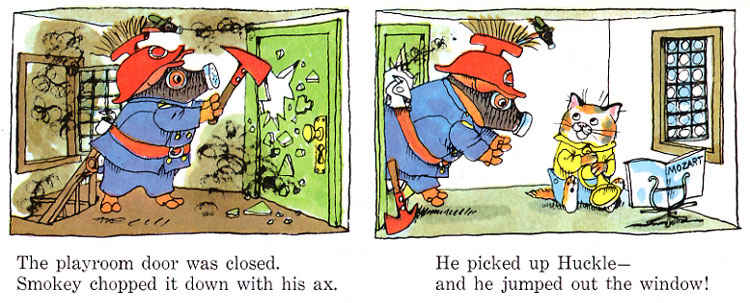

He didn't write stories, he drew them in pencil on frosted acetate. Then

he painted through the entire stack color by color. First he'd colorize

everything meant to be red, then blue, yellow, and so forth. He'd do all

the pigs, then all the cats, then all the dogs. He preferred a bright,

simple palette of Winsor & Newton Designers Colors: Flame Red, Carthamus

Pink, Cadmium Orange and Primrose, Golden Yellow, Linden Green, Permanent

Green Middle and Deep, Winsor Green, Sky Blue, Winsor Blue, Burnt Sienna,

Raw and Burnt Umber, Chinese Orange, and Spektrum Violet.

When

the blueboards and pencil sketches were finished, he juxtaposed alongside

them blocks of text affixed with Scotch tape meant to carry readers along

through a loose narrative. He punched his ideas out on an old portable

typewriter, usually by way of the hunt-and-peck method, and many of these

paper scraps contained typos, spelling and syntax errors—even poor grammar.

But an editor could fix that up. Being smarty-smart all the time wasn't

necessary for a guy who hated school. Richard Scarry was a slapstick make-'em-laugh

funny man first, an "educator" second. His singular purpose:

entertain the kids. Be funny without being stupid. Don't do it in a way

they've seen a million times before. And whatever the cost, don't be boring.

He hated white space, deliberately filling up each page with as much

pictorial matter as possible. By doing so, young readers would want to

scan the books over and over, possibly finding something new with each

reading.

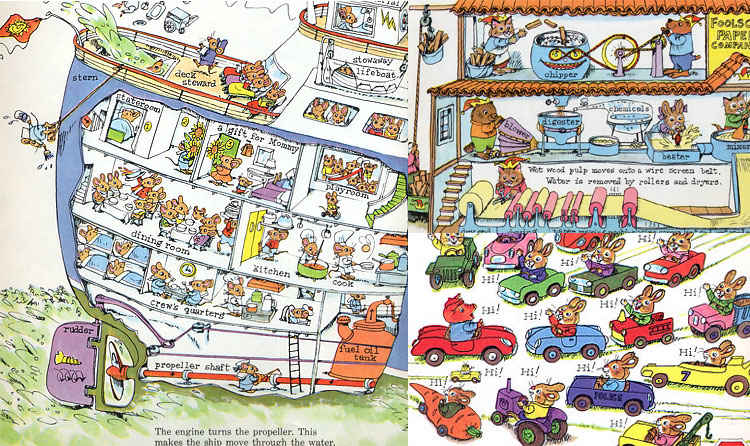

Exploded views and simplified cut-away diagrams became commonplace throughout

his work. Editors noticed that Scarry's "children's books" were

becoming more complicated—his illustrations had grown so dense that

even a single page required endless hours of fact-checking and research.

Scarry's personal library (and by proxy, that of his editors) contained

encyclopedias, travel books, cardboard boxes filled with pictures torn

from old magazines, restaurant menus, vacation snapshots from every corner

of the globe during his military travels, and rubber-banded rolls of architectural

diagrams. He would outdo himself time reading.

Exploded views and simplified cut-away diagrams became commonplace throughout

his work. Editors noticed that Scarry's "children's books" were

becoming more complicated—his illustrations had grown so dense that

even a single page required endless hours of fact-checking and research.

Scarry's personal library (and by proxy, that of his editors) contained

encyclopedias, travel books, cardboard boxes filled with pictures torn

from old magazines, restaurant menus, vacation snapshots from every corner

of the globe during his military travels, and rubber-banded rolls of architectural

diagrams. He would outdo himself time  and

time again, from What Do People Do All Day to Richard Scarry's

Great Big Schoolhouse. At this stage of the game, his advances were

upwards of $105,000. and

time again, from What Do People Do All Day to Richard Scarry's

Great Big Schoolhouse. At this stage of the game, his advances were

upwards of $105,000.

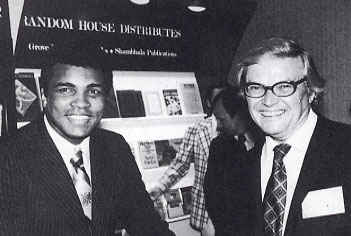

One day some of these sketches were sitting on Scarry's editor's desk,

and Theodore Geisel (aka Dr. Seuss) unexpectedly strolled into

the office. Dr. Seuss wandered over to the table and began idly leafing

through Scarry's preliminary drawings. He didn't ask whose work it was.

Seuss and Scarry were two very different men. Seuss worked primarily with

words, Scarry with pictures. Suddenly Seuss stopped flipping and asked,

"Does this sort of thing sell?" It sold very well indeed.

In fact, Richard Scarry's books had been outselling Seuss's for years.

But neither author would ever really know that, due to the "good

diplomacy" management style strictly upheld at Random House.

Richard also

admired the work of Beatrix Potter, but he made every effort not to copy

her style. Yes, they both put articles of clothing on anthropomorphic

animals, but she spent countless hours studying them and making realistic

drawings. The reader never thinks of her characters as human. Scarry would

occasionally emphasize a particular animal habit (Bananas Gorilla likes

bananas and t Richard also

admired the work of Beatrix Potter, but he made every effort not to copy

her style. Yes, they both put articles of clothing on anthropomorphic

animals, but she spent countless hours studying them and making realistic

drawings. The reader never thinks of her characters as human. Scarry would

occasionally emphasize a particular animal habit (Bananas Gorilla likes

bananas and t ries

to steal them, Lowly Worm pokes his way through apples, and there's always

a hole in the roof of a bus to accommodate a giraffe's long neck)—but

these characteristics are a source of incidental humor, not as a means

of establishing a figure's identity as an animal. ries

to steal them, Lowly Worm pokes his way through apples, and there's always

a hole in the roof of a bus to accommodate a giraffe's long neck)—but

these characteristics are a source of incidental humor, not as a means

of establishing a figure's identity as an animal.

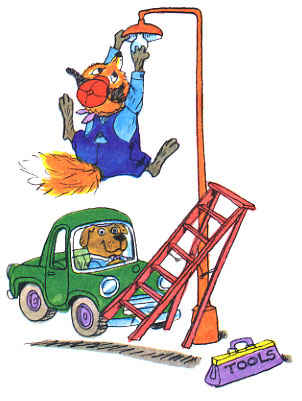

The real reason he worked this way was that drawing animals was more

fun than drawing humans. Fun to draw, fun for kids, and fun for the adults

compelled by their children to read these books over  and

over. "If I show a human father falling off a ladder or getting into

a monstrous auto crash," he remarked, "it suggests danger and

getting hurt. If I show Father Pig in the same situation, nothing more

is hurt than his dignity. Also, a chocolate cake can explode out of Mother

Bear's oven." and

over. "If I show a human father falling off a ladder or getting into

a monstrous auto crash," he remarked, "it suggests danger and

getting hurt. If I show Father Pig in the same situation, nothing more

is hurt than his dignity. Also, a chocolate cake can explode out of Mother

Bear's oven."

To Richard, pigs, cats, bears, hippos, giraffes, lions and so forth were

not animals. They were real people living normal lives, performing everyday

tasks like. He made every effort to completely subtract elements of delineated

racial characteristics, believing that even a simple illustration of a

girl with blonde hair could not be fully related to by a girl with dark

hair. But both girls might relate and respond to bunny rabbits.

After

twenty years with Golden Books, Scarry moved across Madison Avenue to

Random House. While the publishing company was pleased as punch to receive

him, it was here that Richard Scarry started to receive his first batch

of hate mail. After

twenty years with Golden Books, Scarry moved across Madison Avenue to

Random House. While the publishing company was pleased as punch to receive

him, it was here that Richard Scarry started to receive his first batch

of hate mail.

Letters

of complaint poured in about the roles played by women in reformed-gigolo

Scarry's picture books. The increasing importance and acceptance of the

feminist movement in the United States called into question why a large

percentage of Scarry's female characters were depicted as housewives:

cooking, cleaning, washing dishes. Scarry, now a significantly older man,

was a bit incensed. He maintained that because his characters were animals,

and because most wore trousers, it was difficult to discern whether

or not a worker was a man or a woman. Besides, most of the women characters

dressed just like men anyway, a trait arguably mirrored by the feminists

themselves. Random House urged him to change with the times, and he wasn't

too difficult to persuade once he learned sales were being affected. His

Best Word Book Ever was still his number-one bestseller, and it

was accused of being the worst offender. And so he drew new art, using

women workers on the job, and depicting men taking a more active interest

in household duties. Letters

of complaint poured in about the roles played by women in reformed-gigolo

Scarry's picture books. The increasing importance and acceptance of the

feminist movement in the United States called into question why a large

percentage of Scarry's female characters were depicted as housewives:

cooking, cleaning, washing dishes. Scarry, now a significantly older man,

was a bit incensed. He maintained that because his characters were animals,

and because most wore trousers, it was difficult to discern whether

or not a worker was a man or a woman. Besides, most of the women characters

dressed just like men anyway, a trait arguably mirrored by the feminists

themselves. Random House urged him to change with the times, and he wasn't

too difficult to persuade once he learned sales were being affected. His

Best Word Book Ever was still his number-one bestseller, and it

was accused of being the worst offender. And so he drew new art, using

women workers on the job, and depicting men taking a more active interest

in household duties.

Then,

more scandal. Racial issues began to surface when Random House re-released

Busy, Busy World. This picture book had been a pinnacle of achievement

for Scarry when he was at Golden Books. It was a labor of love, incorporating

his fondness for travel and appreciation for other cultures. But changing

times and buckets of hate mail at Random House suggested that characters

like Manuel of Mexico (with a pot of refried beans stuck on his head),

Ah-Choo the near-sighted panda bear from Hong Kong, and Angus the Scottish

bagpiper were no longer acceptable role models for children. Random House

quietly subtracted some of Scarry's best stories from future distribution,

including the much-loved vignette of Patrick Pig, who shouts "UP

THE IRISH" after kissing the Blarney stone. That story can be found

in earlier copies of Golden Book's Busy Busy World, in the remainder

bin of your local thrift store. Then,

more scandal. Racial issues began to surface when Random House re-released

Busy, Busy World. This picture book had been a pinnacle of achievement

for Scarry when he was at Golden Books. It was a labor of love, incorporating

his fondness for travel and appreciation for other cultures. But changing

times and buckets of hate mail at Random House suggested that characters

like Manuel of Mexico (with a pot of refried beans stuck on his head),

Ah-Choo the near-sighted panda bear from Hong Kong, and Angus the Scottish

bagpiper were no longer acceptable role models for children. Random House

quietly subtracted some of Scarry's best stories from future distribution,

including the much-loved vignette of Patrick Pig, who shouts "UP

THE IRISH" after kissing the Blarney stone. That story can be found

in earlier copies of Golden Book's Busy Busy World, in the remainder

bin of your local thrift store.

Scarry

never received a single award. None of his drawings were ever selected

by the New York Times as among the best of the year, and he never

won a Caldecott Honor. It was widely considered among awards committees

that not only was he too popular, he sold too many books.

The millions of dollars he earned were considered his "reward"

—his great success disqualifying him from being eligible. Scarry

never received a single award. None of his drawings were ever selected

by the New York Times as among the best of the year, and he never

won a Caldecott Honor. It was widely considered among awards committees

that not only was he too popular, he sold too many books.

The millions of dollars he earned were considered his "reward"

—his great success disqualifying him from being eligible.

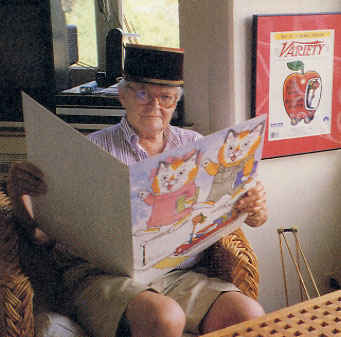

In the 1980's, Richard's eyesight was complicated by macular degeneration,

a progressive disorder which attacks the central part of the retina, causing

gradual loss of vision. His last book, Richard Scarry's Biggest Word

Book Ever was one of his largest accomplishments, weighing in at 15

3/4 x 24 inches. Although Random House was forced to charge $29.00 per

copy, the entire printing run quickly sold out.

Richard later developed cancer of the esophagus. An operation to remove

the tumor, along with follow-up chemotherapy and evacuation of excess

fluid from his lungs was not enough to prevent a fatal heart attack. He

died in his home on April 30, 1994, at age 74. His wife Patsy died in

1995. Their son Huck carries on the tradition, writing and illustrating

fanciful, educational books for children.

|