|

Douglas Adams You have to respect a man who can write something like this:

You have to respect a man who can write something like this:

It is known that there is an infinite number of worlds, simply because there is an infinite amount of space for them to be in. However, not every one of them is inhabited. Therefore, there must be a finite number of inhabited worlds. Any finite number divided by infinity is as near to nothing as makes no odds, so the average population of all the planets in the universe can be said to be zero. From this it follows that the population of the universe is also zero, and that any people you may meet from time to time are merely the product of a deranged imagination.The preceding passage is, of course, the product of a deranged imagination of the product of a deranged imagination by the name of Douglas Noel Adams—DNA for short. Adams got his start in the entertainment industry in the U.K. during the early 1970s, when the concept of comedy had been hijacked by a group of overeducated lunatics known as Monty Python. It was a ripe environment for the overeducated Adams, who went to the University of Cambridge like many of the Pythons.

The idea for the Guide came to Adams while he was lying drunk in a field in Austria, with a virtually useless Hitchhiker's Guide to Europe at his side. (It was useless because he didn't speak German, a considerable problem given his locale.) It's easy to see how The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy relates back to this origin.

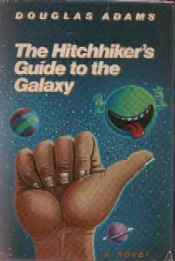

Not only is it a wholly remarkable book, it is also a highly successful one—more popular than the Celestial Home Care Omnibus, better selling than Fifty-three More Things to do in Zero Gravity, and more controversial than Oolon Colluphid's trilogy of philosophical blockbusters Where God Went Wrong, Some More of God's Greatest Mistakes and Who is this God Person Anyway?  The book's chief selling point is that it has the words "DON'T PANIC" inscribed in "large, friendly letters" on the cover.

The book's chief selling point is that it has the words "DON'T PANIC" inscribed in "large, friendly letters" on the cover.

The original radio series (12 half-hour episodes over two seasons) was the purest, and probably the funniest, incarnation of the story, which focuses on Arthur Dent, who is rescued from the complete destruction of the earth by his Much hilarity ensues, and unlike the many other times you will read that phrase during the course of your lifetime, it's actually true in this instance. When it debuted, the guide was a cutting satire on humanity and its obsessive sense of self-importance. The radio show's keen humor was accented by Adams' wild imagination, which played out in entries from Guide delivered with pitch-perfect British drollery by voice actor Peter Jones.

After the success of the radio shows, the Guide spread to several other media, including two great books based on the original two radio seasons, and three more merely adequate books, a text adventure computer game, a BBC television show based on the radio series with great writing and excruciatingly bad production values, a book of the radio scripts, two entirely mediocre radio series based on the three merely adequate books, and a merely adequate movie based more or less on the original series.

The later installments of the book series lacked the hysterical humor of the originals, as the characters and concepts grew fat and slightly complacent. They were still funny, of course, and better than 90 percent of the science fiction published any given year.

Although the Guide was his best-known creation, Adams spent creative capital on other projects as well. The original idea of the Hitchhiker's Guide was an early conception of how hypertext might work. An early Mac adopter, Adams was fascinated by the possibilities of hypertext and involved himself in various projects along the way to the World Wide Web. The Guide itself was a conceptual precursor of the wiki, and one of Adam's projects was a wiki-style version of the Guide for earthlings known as h2g2. Adams also wrote two novels about Dirk Gently, a holistic detective who solves cases by studying the "fundamental interconnectedness of all things." The books were well-received critically, but failed to dent the cultural zeitgeist with the same impact as the five-book Hitchhikers trilogy. A graphic adventure computer game, Starship Titanic, fared better, although Adams left the novelization to Python alum Terry Jones because he couldn't cope with the deadline. "I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by," Adams claimed notoriously. Sadly, there are times when deadlines matter—such as when you're about to drop dead unexpectedly at a tragically young age.

He also left a heaping pile of unfinished projects, whose deadlines whooshed after him into the afterlife (or rather, the apres vie). The Hitchhikers movie was at the top of the list. Adams was a "radical atheist," by his own description, so he's probably not hanging about somewhere to see the Hitchhikers product machine grind on in his absence. The game was scrapped, but the novel was published as an unfinished (and unfocused) work, good for a few weeks on the bestseller lists. The BBC is producing additional radio shows, based on rough notes Adams left behind, and there may well be a movie sequel (probably contingent on robust overseas grosses based on the early returns). "Ghastly, isn't it?" as Marvin might say. |

Adams worked short stints as a writer on Monty Python's Flying Circus and

Adams worked short stints as a writer on Monty Python's Flying Circus and  The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (the radio series, the subsequent TV series, book series, computer game and movie) is about a book called The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, a semi-complete compendium of somewhat accurate instructions on how to get around the galaxy for less than 30 Altarian dollars a day. According to Adams:

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (the radio series, the subsequent TV series, book series, computer game and movie) is about a book called The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, a semi-complete compendium of somewhat accurate instructions on how to get around the galaxy for less than 30 Altarian dollars a day. According to Adams:

friend, Ford Prefect, who turns out to be an alien researcher for the guide. Supporting characters included two-headed Galactic President Zaphod Beeblebrox, Marvin the Paranoid Android, Earth girl Trillian, planetary designer Slartibartfast and Eccentrica Gallumbits, the triple-breasted whore of Eroticon 6.

friend, Ford Prefect, who turns out to be an alien researcher for the guide. Supporting characters included two-headed Galactic President Zaphod Beeblebrox, Marvin the Paranoid Android, Earth girl Trillian, planetary designer Slartibartfast and Eccentrica Gallumbits, the triple-breasted whore of Eroticon 6.  If you've read this far into an article on Douglas Adams, you don't need to have the meaning of 42 or the importance of towels explained to you. You may also remember such highlights as the shoe event horizon, the offensiveness of the word belgium and the secret of how to fly. If you haven't gotten that far into the series, we won't certainly spoil the fun.

If you've read this far into an article on Douglas Adams, you don't need to have the meaning of 42 or the importance of towels explained to you. You may also remember such highlights as the shoe event horizon, the offensiveness of the word belgium and the secret of how to fly. If you haven't gotten that far into the series, we won't certainly spoil the fun.  The Guide had a fanatical cult following, so it's understandable that Adams would give his clamoring public more and more Hitchhikers installments. The problem was that the Hitchhikers well was not especially deep, even if the water did sparkle.

The Guide had a fanatical cult following, so it's understandable that Adams would give his clamoring public more and more Hitchhikers installments. The problem was that the Hitchhikers well was not especially deep, even if the water did sparkle.  But the energy of the originals flagged a little with each iteration. The 2005 movie release—chock full of punchlines and eye-popping special effects—was the fourth time around the block for the original nugget of story, and it felt like the fourth time.

But the energy of the originals flagged a little with each iteration. The 2005 movie release—chock full of punchlines and eye-popping special effects—was the fourth time around the block for the original nugget of story, and it felt like the fourth time.  Adams died of a

Adams died of a  The film had been languishing in development hell for well over a decade, and Adams was toiling away on the script when he died. Another screenwriter took over after his passing, which may account for the movie's tepid reception. Adams was also working on a new Hitchhikers game and a novel that hadn't quite decided whether it was a Hitchhikers project or a Dirk Gently production.

The film had been languishing in development hell for well over a decade, and Adams was toiling away on the script when he died. Another screenwriter took over after his passing, which may account for the movie's tepid reception. Adams was also working on a new Hitchhikers game and a novel that hadn't quite decided whether it was a Hitchhikers project or a Dirk Gently production.